History, politics and death: How Lazio-Roma became Italy's fiercest rivalry

For the April 2009 FourFourTwo magazine, Andy Mitten visited the peninsula’s capital to discover a long-running climate of animosity and hatred…

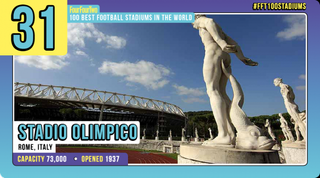

“There’s blood on the bridge. Don’t go there.”FourFourTwo has just stepped off a packed bus outside Rome’s Stadio Olimpico. The blue flashing lights of police riot vans add further chill to the cold night air.

Robocops sweep between the traffic, their batons poised. A cry goes up from an officer and police swarm around a group of Ultras, arrest a handful and then march them to a wagon holding temporary cells.

You don’t expect football violence to be played out amid the granite statutes, boulevards and rich mosaics at the foot of Monte Mario

Something sinister has also just taken place between the Tiber River and the beautiful Cyprus trees which surround the stadium. Four Manchester United fans appear.

“Don’t walk there,” one says, pointing towards the police vans. Another warns against going to the bridge, a notorious ambush point of Roma’s violent ultras. Several United fans were stabbed there six months ago. You don’t expect football violence to be played out amid the granite statutes, boulevards and rich mosaics at the foot of Monte Mario.

It’s December 2007 and United are back in Rome. Lessons have not been learnt and there’s more trouble, just as there always seems to be when English teams play in the Italian capital. FourFourTwo's mobile starts to buzz with texts. ‘Reports that five United stabbed,’ says one. ‘Be careful.’ Caution is indeed exercised, but it was still very, very moody.

On a comedown at the hotel later, FFT hears: “You think that was bad, go to a Roma vs Lazio game.” It’s only from the receptionist, but the reputation of Il Derby della Capitale is ferocious.

Civil war

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

“The Rome Derby is the most intense in Italy,” states Aurelio Capaldi, football journalist for Italian state broadcaster Rai.

Apart from the Old Firm, nothing compares with the Rome Derby. The build-up is huge, nothing else matters

“Apart from the Old Firm, nothing compares with the derby of the Big Dome (St. Peter’s),” says former Lazio Ultra and player Paolo Di Canio. Having played in five derbies, from Milan to London, he should know.

“The build-up is huge, nothing else matters,” adds Di Canio. “Roma and Lazio fans care more about winning the derby than where they finish in the league.”

“Points matter in the Milan derby because Inter and Milan are usually chasing trophies,” Capaldi agrees. “In Rome it’s different. Only five Scudetti have ever gone to the capital. It’s all about the derby.”

There are other factors. While the Milan Derby is diluted by the existence of Juventus in nearby Turin - indeed the Inter vs Juventus clash is known as ‘the Derby of Italy’ because both clubs boast nationwide fan bases – the Rome derby only really matters in Rome.

Roma and Lazio focus on each other. Football is a serious issue in the eternal city and it affects Roman life

“Roma and Lazio focus on each other,” continues Capaldi. “Football is a serious issue in the eternal city and it affects Roman life. With good weather, Romans live outdoors far more than people in Milan or Turin. They talk football in the squares, parks and bars. Roma and Lazio fans always tease each other about the derby.

“The Romans’ personality is suited to football– ironic and humorous. The Milanese character is far more reserved and the population of the north is diluted by many southerners who moved for work. In Rome, you are Roman. And you’re either Lazio or Roma.”

Changed days

It’s Easter 2008. The winter gloom that enveloped the December trip is receding and Rome is full of tourists taking in world-class monuments like the Roman ruins of the Colosseum and the Renaissance grandeur of St. Peter’s.

Both clubs have suffered sharp decreases in crowds since the turn of the millennium, with Roma’s average crowd dropping from 58,000 to less than 40,000 and Lazio’s from 53,000 to 29,000

Groups of appallingly dressed middle-aged Americans follow uninterested tour leaders holding yellow flags. They talk of Bernini’s Baroque fountains, the Spanish Steps and of hoping to see the Pope’s Easter address. But there’s another big event in town and FourFourTwo walks the other way, towards the Stadio Olimpico, which Lazio and Roma share, for a league game. Back towards the bridge.

Lazio are mid-table in Serie A and Roma second. It’s a Lazio home game, but 30,000 of the anticipated 70,000 crowd will be backing Roma, whose fans retain their Curva behind the south goal. Both clubs have suffered sharp decreases in crowds since the turn of the millennium, with Roma’s average crowd dropping from 58,000 to less than 40,000 and Lazio’s from 53,000 to 29,000.

Three explanations are advanced: the proliferation of pay-per-view television meaning that more fans stay at home or in bars to watch their team, a decline in the standard of both teams – although Roma have improved greatly in recent years. And it is often unsafe to watch football in Italy.

It’s two hours before kick off and the fans crossing the bridge towards the blaze of Olimpico’s lights wear Roma’s red and yellow. Roma have always been the better supported of the two clubs. It’s assumed that this is a designated entrance for their fans until a light blue Lazio scarf is spotted, then another, the fans walking unhindered past the thousands of motorbikes that spectators have left by the statues of former Olympians.

Hundreds of Liverpool, Manchester United and Middlesbrough fans have been attacked for the crime of wearing their colours outside the Olimpico, but tonight the atmosphere is maudlin, not murderous.

A rare ceasefire

The Lazio team bus cuts through the city’s heavy traffic with a five-car police escort, but a horn would suffice, such is the indifference shown to them. A glance at the headlines in the voracious Italian sport dailies explains why the mood is so different for a derby littered with a history of violence, corruption and passion.

Rome-based Corriere Dello Sport leads with: ‘Emotion Derby.’ In November, Lazio fan Gabriele Sandri, a 26-year-old DJ, was shot dead by police in an accident at a Tuscan motorway service station after Lazio and Juventus fans had rioted.

That night, as Italian society attempted to comprehend another football related death, fans rioted nationwide. Lazio fans blocked the bridge over the Tiber and torched cars.

If the hardcore fans hate anyone more than each other in Rome, it’s the police, and for one game only, the Ultra groups of both clubs who yield significant power have agreed to pay their respects.

At an official level, a campaign name ‘Gimme Smile’ has been concocted employing cartoon like characters to promote goodwill. Few children will appreciate them. Italy may have an ageing population, but there are virtually no children in the stadium. Besides, it’s the curva who control the mood, not the authorities.

Flanked by both Ultra leaders, Roma captain Francesco Totti and Lazio’s Tommaso Rocchi walk towards the Lazio curva and a giant fan painting showing an image of Gabriele. Gabriele’s brother stands solemnly between the two captains, their arms joined around the rival Ultra leaders – stocky forty-something Stallone look-a-likes in baseball caps, trainers and pseudo army pants.

The relationship between Italian players and Ultras is complex, but such is their power, Totti, a living deity among Roma fans, will ignore media criticism to attend Ultra meetings, funerals and weddings.

The group are greeted by a respectful silence and the ambience remains sombre as the Roma Ultras raise huge banners for their hated rivals at the other end to read: ‘IN THE LIGHT BLUE SKY, A STAR SHINES. CIAO GABRIELE’, ‘TEARS DON’T KNOW PAIN’, ‘GABRIELE. YOU ARE ALWAYS IN OUR HEARTS’, ‘GABI IS ONE OF US.’

In the past, both fans have used the same sky theme in provocation. In 2000, a banner on the Roma curva read: “Look up. Only the sky is bigger than you.” Lazio cleverly replied immediately: “You’re right, it’s blue and white.” Lazio fans were waiting, literally, with a giant blank canvas and paint.

The mood changes before kick off. Fireworks are let off from both ends, which are packed behind a moat and toughened glass screens to their 24,600 limits. They become a swirl of noise and colour but they lack the stunning choreographies of past derbies. It’s a shame.

“The Roma vs Lazio derby is the best show in Italy,” says Rodrigo Cacho, a Roma fan lecturing at Cambridge University. “The fans like to outdo each other with displays. As well as being friendly, outspoken and convinced that they know everything, Romans are fixed with the idea that they are at the centre of the world - neither northern nor southern - but special and living in the most beautiful city.”

The Roma vs Lazio derby is the best show in Italy. Romans are fixed with the idea that they are at the centre of the world, neither northern nor southern, but special and living in the most beautiful city

A match ticket on the curva costs just £15 and despite the athletics track, there’s barely a poor seat in the 80,000 capacity arena. In the main stand tickets cost over £100 and those who pay do so for refined company rather than better sightlines.

There, immaculately attired men show off their elegant females, none of whom concentrate on the game. Actors, politicians (there’s an election approaching and candidates want to be seen to like calcio) and Roman socialites are there on view.

“She was the first black girl to win Miss Italy in 1998,” says our Italian translator Andre, a Milan fan and semi professional footballer who has travelled down from Parma. The Lazio fans have history on their side as well as wealth and glamour.

In the beginning

Taking their name from the region around Rome, Società Sportiva Lazio was founded in 1900 by an Italian army officer, Luigi Bigarelli. They adopted Greek colours and played in wealthy northern suburbs like Parioli, close to their Rondinella home, from 1914-31.

Pressure was placed on Lazio to join the merger, forming a mighty Roma fit to challenge the northern giants from Milan and Turin. They resisted

Fascist leader Benito Mussolini was a fan and took his kids to games. II Duce’s plans for building a capital of the new Roman Empire included a football stadium. Before his grand scheme eventually saw Olimpico built, Lazio moved to the Fascist Party Stadium (the PNF) in 1931. The stadium staged the 1934 World Cup final but by this time, Lazio had a rival.

Associazione Sportiva (AS) Roma were formed in 1927 from a merger of four small clubs, Alba, Fortitudo, Pro Roma and Roman. Local patriot and Fascist politician Italo Foschi was the driving force. Pressure was also placed on Lazio to join the merger, forming a mighty Roma fit to challenge the northern giants from Milan and Turin. Mussolini wanted to promote Rome as the capital of a new rationalised Italy partly through football. Lazio resisted.

Roma played their games in the wooden Campo Testaccio district to the south of the city, a working class district which is still an area of high Roma support. It was a glorious venue full of character and the Giallorossi (red and yellows) lost just 26 games there in 11 years up to 1940 as Roma overshadowed their rivals and provided two of Italy’s 1934 World Cup winners.

Il Duce took Italy into the Second World War and Roma reluctantly left their much loved but too cramped ground to share the bigger Fascist stadium with the Biancocelesti (light blues) of Lazio. Older Roma fans declare they have been homeless from that day.

Roma won their first league title in 1941-42 – the first time it had gone south of Bologna - although it wasn’t without suspicion. In a key derby game, a bizarre last minute own-goal went Roma’s way

Roma had no trouble with the move and won their first league title in 1941-42 – the first time it had gone south of Bologna - although it wasn’t without suspicion. In a key derby game, a bizarre last minute own goal went Roma’s way. In 1953, both clubs left the PNF stadium for the new Olimpico across the Tiber, built for the 1960 Olympics.

Neither club troubled Italy’s trophy engravers much, though Roma won the UEFA Cup in 1961 and the Italian Cup in 1964. Lazio then enjoyed an upturn in fortunes, winning a first title under tough Argentinian coach Juan Carlos Lorenzo, who’d led the notorious Estudiantes side of the 1960s.

Unmovable Paolo

Geographic divisions have blurred, but traditionally Roma fans were more inner city left wing, while Lazio were suburban right wing and middle class. By the early 1970s Lazio had attracted Ultras, fired up by the political tensions of the time, from Rome’s cramped southern housing projects, like Quarticciolo, where Paolo Di Canio was born in 1968.

“I have always felt a special affinity towards the weak, the disadvantaged, the unloved,” explains Di Canio. “And I loved their symbol, the Lazio eagle.”

Lazio’s Ultra movement became focussed on one group, Eagles Supporters, but they were usurped by the predominantly fascist Irriducibili (Unmovables). Member Di Canio once sprayed ‘Roma is shit and their curva stinks’ on a wall in his neighbourhood and while a player in Lazio’s youth teams, he would play on a Saturday and then travel overnight to away first team matches with the Irriducibili, by then Italy’s biggest Ultra group.

“I kept the club in the dark about my travels. If they had known that I spent my Sundays with the Irriducibili, visiting far flung corners of Italy, they would probably have kicked me out of the youth academy,” he says. He was spotted by the Lazio physio at one away game at Atalanta and warned to stay away, a warning he didn’t heed. Di Canio was five yards away when the head of Bergamo’s police was stabbed.

An Ultra died during a derby game in 1979 after being hit by a flare thrown by a Roma fan, two years after young midfielder Luciano Cecconi was shot dead in a jeweller’s store

“What I loved about the Irriducibili was that we only travelled at night. We’d set off at 11.15pm from Termini (Rome’s train station). The trips were more eventful than the matches themselves.” Di Canio never lost the ultra in him. With such a following, Lazio were never far from tragedy.

An Ultra died during a derby game in 1979 after being hit by a flare thrown by a Roma fan, two years after young midfielder Luciano Cecconi was shot dead in a jeweller’s store. He was dressed as a robber for a joke. In 1980, Lazio and Milan were forcibly relegated to Serie B in 1980 after a scandal concerning illegal bets on their own matches. It wasn’t the first nor last time those clubs would be embroiled in corruption.

Roma’s Ultras thrived too - groups like Commando Ultras Curva Sud (CUCS) and Boys Roma asserting their dominance at various points. Over time, their left wing sympathies shifted right.

Trophies continued to elude teams from the capital as Italy’s big three dominated. A second Scudetto came to Roma in 1983 with a side spearheaded by three-time Serie A top scorer Roberto Pruzzo, the Brazilian playmaker Falcao (who far left Roma fans compared with Chairman Mao, partly because their names rhymed), winger Bruno Conti and player of the year Pietro Vierchowod.

I Lupi (the Wolves) reached the European Cup final a year later and with the match staged at the Stadio Olimpico, were favourites against Liverpool. Roma froze and lost on penalties to Bruce Grobbelaar’s wobbly knees. Violence marred the game’s aftermath, with Lazio fans providing weapons to Liverpool fans to defend themselves against Roma.

By 1988, a teenage Di Canio was in Lazio’s first team and although he didn’t last long in his first spell at the club before playing for Juventus, Napoli, Milan, Celtic, Sheffield Wednesday and West Ham, he did score in a derby.

“I just ran straight towards the Curva Sud, where the Roma fans were sitting,” he recalled. “The roar at my back, from Lazio’s Curva Nord, was spurring me on. I ran under the fans, finger raised, face contorted in a mixture of ecstasy, relief and fury.”

The Olimpico was remodelled for the 1990 World Cup, but the Fascist entrance still stands, Mussolini dedications and all. The Azzurri, the Italian nation team, plays every third home game there.

Money brings success

By the early 90s, both Roma and Lazio had acquired serious backers as presidents. Roma won the UEFA Cup in 1991. At Lazio, Paul Gascoigne and ‘Beppe’ Signori were bought by the financier Sergio Cragnotti. With Alen Boksic, Karl-Heinze Riedle and Aron Winter (who was abused by his own fans for being a “black Jew”) Lazio became top five regulars.

Both clubs spent big, creating cosmopolitan and powerful squads and trying also to mimic the commercial success of big British clubs. Lazio became the first Italian club to go public and in 1998 Roma asked Edward Freedman, the merchandise maverick who revolutionised Manchester United’s fortunes to do the same for them.

“I knew it wouldn’t be easy because I’d already dealt with Lazio,” says Londoner Freedman. “At Tottenham, I was a part of the negotiations to sell Paul Gascoigne. Their merchandise operation was non-existent; they’d never even seen a t-shirt with club colours on until we suggested they printed 10,000 Gascoigne t-shirts. They sold out.”

Roma president, industrialist Francesco Sensi, flew to London to meet Freedman. “Sensi ran everything there,” says Freedman. “And like other Italian presidents he picked the team and decided which players to buy, often off the back of a video. English coaches have it easy. There was no forward thinking in Rome. Nor were there match programmes, club stores or official merchandise. We couldn’t replicate what we had done in Manchester because the market was not mature.”

The Roman football arms race continued, but it wasn’t until Lazio appointed Sven Goran Eriksson that they turned into winners, lifting the 1999 Cup Winners’ Cup and the league and cup double in their centenary a year later with players like Juan Sebastian Veron, Pavel Nedved, Sinisa Mihajlovic, Alessandro Nesta, Diego Simeone and £35 million Hernan Crespo.

At the turn of the Millenium Rome was Italy’s political and football capital. Buoyed by success, Cragnotti upped the ante by spending £28m on Mendietta, who played just 20 games. As their wage bill soared, form dipped. Salaries went unpaid, stars left and debts mounted.

Cragnotti was eventually declared bankrupt and was arrested on charges of false accounting and fraud, then a new Lazio president cut a deal with the government to pay off back taxes over 24 years.

In 2001, a Roma side managed by Fabio Capello won their first Scudetto for almost two decades with a side including Gabriel Batistuta, Vincent Candela, Vincenzo Montella, Aldair, Cafu, Emerson, Walter Samuel, Marco Delvecchio and a young, home-grown Francesco Totti. Capello is not popular among Roma fans. “He betrayed Rome,” says Ultra, Francesco, “He said he would never go to Juve. And then he went...”

Roma’s impetus could not be maintained, FIFA blocked them from buying players and, like Lazio, they offloaded their expensive talent as normal service resumed and the big three up north again dominated.

Troubled past, troubled future

When Lazio made the news, it was usually for the right wing behaviour of their fans. A banner at one derby read: “Team of blacks, curva of Jews.’ Other banners included: “Your home is Auschwitz.” That Roma didn’t have a significant Jewish support didn’t appear to register. Roma fans booed black players too.

The derbies remained in the headlines. A 2004 match was suspended when false rumours were spread among fans that a boy had been killed by the police. A year later, both teams were in danger of relegation and were happy to take a point from the derby. Which is exactly what both teams got.

With 10 minutes left, all fans began to sing ‘Suspend the game’ and ‘Why did we bother?’ La Gazzetta Dello Sport refused to award players a mark for their individual performances. The players were booed off the field, though Di Canio, then 36 and by this time back at Lazio having taken a large cut in wages, threw his shirt at the curva to show that it was covered in sweat. Di Canio was not adverse to the fascist salute and opined that Mussolini was “misunderstood.”

The derby gets underway, with no police present because fans have promised that for this game they will behave. Such is the power of the ultras - and the threat of violence if the police should enter the stadium – this vow is taken seriously.

“Derbies should not be like this,” says Roma fan Francesco, as he sips a cold, tiny Caffe Borghetti. “We are supposed to hate, not respect. They are from the outskirts, they are not real Romans. They should fuck off and leave the city to us.”

Roma take the lead. “Daje!” shout the Roma fans nearby - ‘Get in there!’ with a Roman twang – as their curva explodes. Lazio equalise just before half time and go ahead 12 minutes into the second half. News arrives that Inter have only drawn and Roma push forward, Simone Perrotta making it 2-2. A win will take Roma within four points of Inter.

FFT makes its way onto the Lazio curva for the final minutes, passing stalls selling unofficial merchandise controlled by the ultras inside the stadiums. It’s so packed that it’s dangerous, despite being a seated area. Two minutes into injury time the stadium literally moves when Lazio get their winner, not a welcome sight for any Health and Safety officials, as fists punched the smoky air.

Lazio have won another battle… but Roma will always believe they are winning the eternal war.

This feature first appeared in the June 2008 edition of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe!

World's biggest derbies • More Than a Game

Andy Mitten is Editor at Large of FourFourTwo, interviewing the likes of Lionel Messi, Eric Cantona, Sir Alex Ferguson and Diego Maradona for the magazine. He also founded and is editor of United We Stand, the Manchester United fanzine, and contributes to a number of publications, including GQ, the BBC and The Athletic.