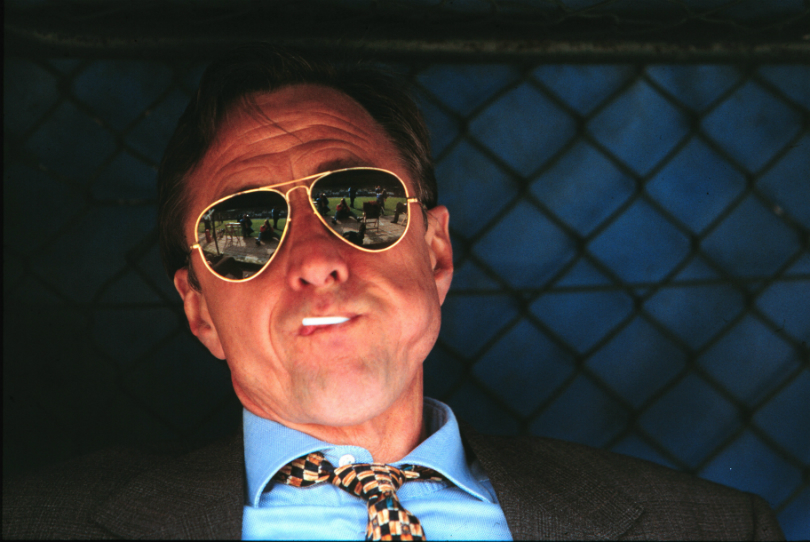

Johan Cruyff: The player, the coach, the legacy

Mesmerising player, revolutionary coach, brilliant pundit: for 40 years, Johan Cruyff has entertained, enthralled and inspired legions of football fans all over the world. Simon Kuper pays tribute to the Dutch master...

When a teenage waif named Jopie Cruyff began training with Ajax’s first team, many of the senior players had already known him for years. Cruyff grew up a few hundred yards from the club’s little stadium, in Amsterdam-East. He had been hanging around the changing room with the first team since he was four. Nonetheless, he surprised his new team-mates. It wasn’t just his brilliance they noticed; it was his mouth. Even while on the ball, the kid never stopped lecturing, telling senior internationals where to run. Maddeningly, he generally turned out to be right.

Think of Cruyff the player and he is on the ball, surrounded by opponents, pointing vigorously in all directions like a busy orchestra conductor. Whatever else was going on, he always made time to tell team-mates (plus the referee, linesmen and his notional manager) what to do. Occasionally he would leave off pointing to accelerate past defenders: well into his thirties he possessed the “sprint within the sprint”, the ability to accelerate even after accelerating. To add to the element of surprise, he could kick the ball with any part of the foot.

A fatherless boy in a changing-room full of men, Cruyff always had to be tougher than anyone else. There are reports of him cheating at Monopoly to beat his own beloved children.

But Cruyff was more than just a great footballer. Unlike Pele and Maradona, he was also a great thinker about football. It’s as if he were the lightbulb and Edison all at once. It’s impossible to identify one man who ‘invented’ British, or Brazilian, football. They just accreted over time. Yet Cruyff – with Rinus Michels, his coach at Ajax – invented Dutch football. The game played today by Holland and Barcelona is a modified version of what the two men came up with in Amsterdam in the mid-1960s. And only now are the Dutch liberating themselves from Cruyff’s style and, above all, from his bizarre personality.

Johan Cruyff (his real name is Cruijff, but foreigners preferred Cruyff) was born on April 25, 1947. His father Manus, a grocer, supplied Ajax with fruit. Cruyff practically grew up at the club. He learned his excellent English – which is probably more correct than his Dutch or Spanish – from eating warm English lunches at the homes of Ajax’s English managers of the 1950s, Keith Spurgeon and Vic Buckingham. “I didn’t have a very long education,” he told me in Barcelona in 2000, “so I learned everything in practice. English too.”

He was just a kid when Manus boasted that one day he would be worth £10,000 and Manus’s death when Cruyff was 12 was probably the formative event of his life. Decades later, he’d still sometimes sit up at night in the family kitchen in Barcelona chatting to his father’s spirit. A fatherless boy in a changing-room full of men, Cruyff always had to be tougher than anyone else. He was. There are reports of him cheating at Monopoly to beat his own beloved children.

The heart of Total Football

Michels had a crazy idea: he was going to turn Ajax into a top international club. The teenage waif he encountered was equally ambitious. Within six years they had done it.

On Cruyff’s debut, Ajax lost 3-1 at a club called GVAV. The reports mostly misspelled his name. After that the 17-year-old didn’t play away games for a while. His mother, who cleaned Ajax’s changing rooms, ruled that he could only play at home because that was safer.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Ajax in those days were a little semi-professional outfit, merely the neighbourhood team of Amsterdam-East. But two months after Cruyff’s debut, on January 22, 1965, a gym teacher for deaf children, Rinus Michels, drove his second-hand Skoda through the gates of De Meer as coach. Michels had a crazy idea: he was going to turn Ajax into a top international club. The teenage waif he encountered was equally ambitious. Within six years they had done it.

The style they invented is now known as ‘total football’. “We never called it that. That came from the English,” said Ajax’s outside-right Sjaak Swart. It was a game of rapid one-touch passing, and players endlessly swapping positions in search of space. Every player had to think like a playmaker. Even the keeper was regarded as the man who started attacks, a sort of outfield player who happened to wear gloves. Wingers and overlapping full-backs kept the field wide. Cruyff could go where he liked, conducting the orchestra with constant improvisation. The world first noticed in 1966, when Ajax beat Liverpool 5-1 on a night so shrouded with mist that hardly anyone saw.

Cruyff and Michels were lucky, of course. By some demographic fluke, half the young men in Amsterdam-East seemed to be world-class footballers. A slow bohemian smoker named Piet Keizer became a fabulous outside-left. Kuki Krol, an Amsterdam resistance hero, produced a willowy defender named Ruud. And one of the few Jews in the neighbourhood to survive the war, a man named Swart, used to take his son Sjakie to Ajax on the back of his bike.

But Cruyff was the most original player in all of Amsterdam-East. His biographer, Nico Scheepmaker, would later remark that whereas other great players were merely two-footed, Cruyff was “four-footed”: hardly anyone had kicked with the outside of his feet before Cruyff did. Cruyff was also astonishingly quick for a chain-smoker – “If they time normally with me, they’re always just too late”, was one of his early bon mots – but he liked to emphasise his quickness of thought. Speed, he explained, was mostly a matter of knowing when to start running. Football was “a game you play with your head”. He was a man who came from Mars and said: “This is how people have always done it, but they were wrong.”

Rethinking, reproducing, rewritting

His personality was so outsized that Michels hired not one but two psychologists to understand him.

Cruyff rethought everything from scratch, without caring about tradition. His greatest goal ever was a case in point. Ajax were playing a friendly against an amateur side, and there were no cameras, but what seems to have happened is that Cruyff was advancing on goal when the keeper came out to confront him. Cruyff turned and began running back with the ball towards his own half. The keeper pursued him until the halfway line, where he realised that Cruyff no longer had the ball. At some point he had backheeled it into the net without breaking stride.

Cruyff didn’t only take responsibility for his own performance. Michels had told him, “If a team-mate makes a mistake, you should have prevented it.” Frank Rijkaard, later a team-mate of Cruyff’s and opponent of Maradona’s, said that Maradona could win a match by himself, but didn’t have Cruyff’s gift of changing the team’s tactics to win it.

Cruyff was a child of his time. Like Franz Beckenbauer, or the students in the streets of Paris in 1968, he was a postwar baby boomer impatient to seize power. The boomers didn’t do deference. Before Cruyff, Dutch footballers had knocked on the chairman’s door to hear what they would be paid. Cruyff shocked Ajax by bringing his father-in-law, Cor Coster, in with him to handle his pay talks.

Cruyff drove everybody at Ajax mad. He never stopped talking, in his working-class Amsterdam accent, with his very own grammar, his penchant for apparently random words (“them on the right is goat’s cheese”), and the shrugs of shoulders that sealed arguments. He once said about his playing career, talking about himself in the second person as usual, “The worst thing is that you always knew everything better. It meant that you were always talking, always correcting.”

His personality was so outsized that Michels hired not one but two psychologists to understand him. Cruyff, always open to new thinking, was happy to talk to them. One shrink, Dolf Grunwald, blamed everything on Cruyff’s father fixation. “Really [he] denies all authority because he – subconsciously – compares everyone to his F. [Father]… If he can stop seeing in Michels the man who is not as good as his f. [father], we’ll have moved on a lot.”

Grunwald said that when attacked Cruyff became “more nervous and talkative”. But when Cruyff felt accepted, he calmed down. “And then his attitude changes too: soft voice, sits down, hangs or lies, talks less, somewhat damp eyes.”

After Grunwald fell out of favour with Michels, Cruyff was sent to Ajax’s other shrink, Roelf Zeven, where he lay on the sofa and talked incessantly about his father-in-law Coster. Here was the missing link in Freud’s work: the father-in-law fixation.

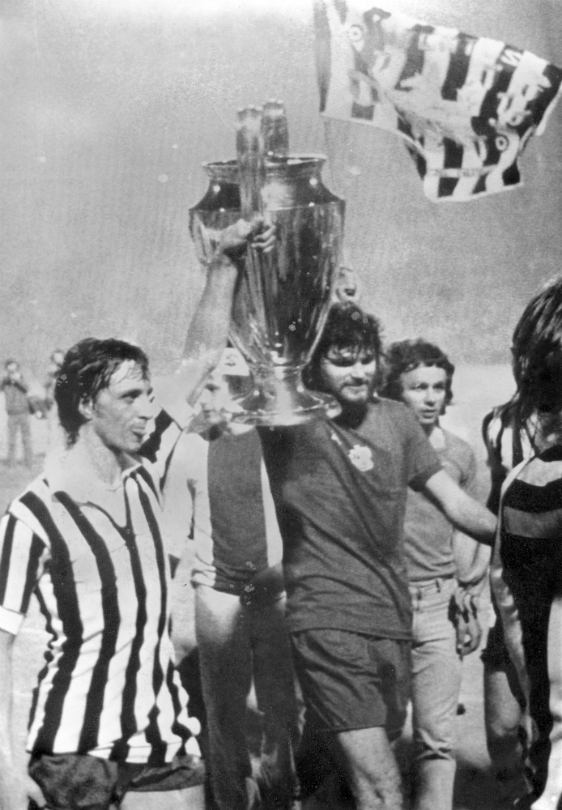

All the talking may have helped. From 1971 to 1973, Cruyff’s Ajax won three straight European Cups. A neighbourhood team from a country that had never done anything in football before, whose stadium would have been small for the English second division, and whose players earned no more than good shopkeepers, had reinvented football.

Then Ajax imploded. Cruyff’s departure was instigated by the player power that he had created. In 1973, the players gathered in a countryside hotel to elect their captain. The majority voted for Keizer, against the incumbent Cruyff. He fled to Barcelona, whereupon the team collapsed. Cruyff would never win another international prize as a player.

The transfer fee Barcelona paid for Cruyff was so big – five million guilders (£1 million) – that the Spanish state wouldn’t countenance it. Barça finally got him into Spain by officially registering him as a piece of agricultural machinery. Cruyff scored twice on his debut, and that season, 1973-74, Barcelona won their first title in 14 years. Afterwards he rushed off to the World Cup in West Germany.

An on-field manager

To Wenger, this showed how hard it was to replicate the fluidity of “total football” if you didn’t have Cruyff himself.

The Dutch team was largely his creation. It was Cruyff, the captain, who told midfielder Arie Haan that he would play as libero. (“Are you crazy?” Haan replied. It proved to be a brilliant idea.) It was Cruyff who had groomed striker Johnny Rep as a youngster at Ajax, sometimes screaming at the bench during games, “Rep must warm up!”

It wasn’t Cruyff’s best month in football, but it was the month that most people saw him and the style he had invented. For many, the Cruyff they know is the Cruyff of his only World Cup.

He notionally spent the tournament at centre-forward, but he was everywhere. He’d sprint down the left wing and cross with the outside of his right foot. He’d drop into midfield and leave centre-backs marking air. He’d drop back just to scream instructions. Arsene Wenger tells the story of Cruyff telling two midfielders to swap positions, and returning 15 minutes later to tell them to swap again. To Wenger, this showed how hard it was to replicate the fluidity of “total football” if you didn’t have Cruyff himself.

Holland hammered Brazil in the semis, but then it all went wrong. The day before the final, the West German tabloid Bild published a story headlined, “Cruyff, Champagne and Naked Girls”, claiming that Dutch players had partied with half-clad lovelies in their hotel pool. Cruyff spent much of the night before the final on the phone to his wife Danny, assuring her the article was a lie. It was a terrible moment for a man who had spent his life building the secure family he had lost aged 12; Cruyff was no George Best. That phone call, says his brother Hennie, is why he played “like a dishrag” in the final. None of it would have happened if their father hadn’t died so early, he added.

Admittedly Cruyff wasn’t a dishrag in the first minute. Dropping back to libero he picked up the ball, ran across half the pitch, and was fouled just outside the German area. The referee Jack Taylor, a Wolverhampton butcher, wrongly gave a penalty. But thereafter, Cruyff mostly hung around in his own half, allowing Berti Vogts to mark him out of the game: Vogts had more scoring chances than Cruyff. Holland lost 2-1. At the reception afterwards, Cruyff buttonholed the Dutch Queen Juliana and asked her to cut taxes.

Cruyff’s next four years at Barcelona were mostly depressing. He got kicked a lot, won no big prizes, and suffered from stress. “If you’re not enjoying [football], you can’t bear the pressure,” he said later.

In 1978, aged only 31, he retired. He refused even to play in the World Cup in Argentina. Many foreigners wrongly believe he was boycotting the Argentine military regime. Rather, haunted by the “swimming pool incident” of 1974, Cruyff stayed home for “family reasons”.

A broadcaster tried to change his mind with a campaign called, ‘Pull Cruyff Over the Line’ (with a theme song by ‘Father Abraham’ of Smurf Song fame). Cruyff briefly mused about playing on condition that he could take his wife. Nothing came of it. And so David Winner argues in his book Brilliant Orange the “swimming pool incident” determined the outcome of two World Cups: 1974 and 1978, in which Holland again lost in the final.

In October 1978, Cruyff played his farewell match: a friendly for Ajax against Bayern Munich, which Ajax lost 0-8. And that would have been the end of Cruyff the Player, but for a pig farm.

In Barcelona, Cruyff and Danny had met a French-Russian chancer named Michel Basilevitch. “The most handsome man in the world,” Danny called him. Basilevitch drove a leased Rolls-Royce and persuaded them to put the bulk of their money in a pig farm. They lost millions. Next thing anyone knew, Cruyff was back, in the US, with the LA Aztecs and later the Washington Diplomats.

Though he loved money with the passion of a man who had grown up without it, he hadn’t come just for the cash. He enjoyed the anonymity of the US and he fell in love with football again.

As ever, there were irritations. In Washington, he drove his British coach Gordon Bradley and his team-mates mad with his fancy ideas. Once, after Bradley had given a team talk and left the room, Cruyff got up, wiped the blackboard clean and said, “Of course we’re going to do it completely differently.”

One of the Brits, Bobby Stokes, said that when the ‘Dips’ bought Cruyff they should also have bought a year’s worth of cotton wool to block the players’ ears. At one point Cruyff grew so despairing of the others that he announced he would limit himself to scoring goals, and did.

The US years provided perhaps the most characteristic Cruyff story: Cruyff and the Florida Bus Driver. What seems to have happened is that just after the Dips landed in Florida for a training camp, the bus driver got lost. Cruyff had never been to the place before but went straight to the front of the bus and dictated the right route. Apparently he often used to direct taxi drivers in cities he didn’t know. He was usually right.

When Cruyff returned to Ajax in 1981, the Dutch were sceptical. The Calvinist Holland of the time distrusted anyone who thought he was special. Cruyff had never been popular at home, where he was known as ‘Nose’ or ‘The Moneywolf’. By now he was 34, with a broken body. Surely he was coming back for the money?

Returning home

Cruyff won two straight league titles with Ajax. When he was 36, and they wouldn’t pay him enough, he switched to Feyenoord and won the title again

He made his second coming in an Ajax-Haarlem game. Early on, he turned two defenders and lobbed the keeper, who was barely off his line. For the next three years, stadiums sold out wherever Cruyff played, as people flocked to see him one last time. He gave us 30-yard passes with the outside of his foot that put team-mates in front of the keeper so unexpectedly that sometimes the TV cameras couldn’t keep up. He gave us the penalty taken in two.

But what he did on the field was only the half of it. The older Cruyff was the most fascinating speaker on football. “Until I was 30 I did everything on feeling,” he said. “After 30 I began to understand why I did the things I did.”

Cruyff said things you could use at any level of football: don’t give a square ball, because if it’s intercepted, the opposition has immediately beaten two men. Don’t pass to a team-mate’s feet, but a yard in front of him so he has to run onto the ball which ups the pace of the game. If you’re playing badly, do simple things. Trap the ball and pass it to the nearest team-mate. Do this a few times, and the feeling that you’re doing things right will restore your confidence. He directly or indirectly improved almost every player in Holland. “That’s logical” – the phrase he used to clinch arguments – became a Dutch cliche.

Cruyff had opinions on everything. He advised Ian Woosnam on his golf swing. He said the traffic lights in Amsterdam were in the wrong places. His old team-mate Wim van Hanegem recalls being taught how to insert coins into a soft-drink machine. He had been wrestling with the machine until Cruyff told him to use “a short, dry throw”. It worked.

Cruyff won two straight league titles with Ajax. When he was 36, and they wouldn’t pay him enough, he switched to Feyenoord and won the title again in his final season. As Scheepmaker said: statistically, buying Cruyff didn’t guarantee you a championship, but it certainly made it immensely more likely. When Cruyff left the field after his last match, Scheepmaker folded up his desk in the press box, and rose to applaud a man who, he said, had made his life richer than it would have been without him.

You’d have thought there’s only one way to take a penalty: shoot at goal. But Cruyff passed the ball forward, Olsen suddenly materialised to pass it back, and Cruyff tapped it into the empty net. The Helmond keeper just watched open-mouthed along with the rest of the country. Many criticised the penalty as risky and presumptuous.

Innovative, irritating and the best manager Holland never had

Gifted strikers like Dennis Bergkamp were sometimes played in defence, to learn how defenders think.

Johan Cruyff’s managerial career lasted just nine years. He was a brilliant and original coach, but his impossible personality brought him down.

The first thing he did on taking over at Ajax in 1986 was to restore Dutch football. At the time, a “Dutch” style no longer existed. Nor had any Dutch team done anything internationally in years.

Cruyff immediately reintroduced “total football”. His Ajax played with two wingers, a “fly goalkeeper” who sometimes showed up near the halfway line, and only three defenders when they had possession. All this baffled many of the players. During one early game, the defender Edo Ophof trotted to the bench in search of instructions. “Work it out yourselves,” Cruyff instructed. It was all part of what he kept calling a “learning process”. For a winner, Cruyff seemed strangely uninterested in results. Sometimes during games he forgot the score. What interested him was the football.

Just as he had as a player, he turned Ajax into a non-stop debating society. “Cruyff thinks he’s always right,” said Ajax’s striker, Johnny Bosman. “The funny thing is, he really is always right.” The manager had new ideas about everything. He brought in opera singer Lo Bello to teach the players how to breathe. He introduced strategies that remain part of the repertoire of Dutch football: for instance, if your team is under the cosh, don’t bring in an extra defender, but send on another attacker, as that will force the opposition to pull somebody back.

He also restructured Ajax’s youth system. Every youth team had to play in the same formation as the first team, and youth coaches had to develop players rather than pile up championships. Gifted strikers like Dennis Bergkamp were sometimes played in defence, to learn how defenders think. To this day, Ajax’s academy operates on Cruyffian lines.

The “learning process” quickly paid off. Cruyff failed to buy his favourite English footballer, Glenn Hoddle, but in 1987 Ajax won the European Cup Winners’ Cup. A year later, Holland won their only big prize, the European Championship, with a coach (Rinus Michels), a style and a team that had largely been formed by Cruyff. Most of the players – chief among them Ruud Gullit, Frank Rijkaard and Marco van Basten – had either played with Cruyff or for him. More than that, they were Cruyffians. Since then, there has never been any doubt about what Holland’s style is. The ideal always remains the same whirling, overlapping, one-touch, top-paced, thinking symphony invented in Amsterdam in the 1960s.

In the 1980s Cruyff finally became a popular hero in his own country. Without Cruyff, Holland wouldn’t have had a footballing tradition. Without a tradition, not many people abroad would have cared about Holland. The nation owed him something.

Success isn't always happy

In his last years at Barcelona, Cruyff grew ever more radical. He thought about giving a defender a pair of gloves and putting him in goal, so as to improve the passing from the back

The only problem with Cruyff was if you had to work with him. His constant criticism drove players mad. Rijkaard walked out of training at Ajax, and sought exile at Milan. The midfielder Gerald Vanenburg told me about playing for Cruyff, “If I look back, I learned one thing: how not to do it.” In 1987, Cruyff left Ajax for the third time in his life, after a row with chairman Ton Harmsen. Soon afterwards Harmsen was invalided by a stroke. “God punishes,” said Cruyff, who seems to view Him as his personal hitman.

The crooked newspaper magnate Robert Maxwell then helicoptered Cruyff to England, hoping to persuade him to join Derby County. But the Dutchman rejected him and returned to Barcelona.

He restructured Barça’s youth system as he had Ajax’s, put Gary Lineker at outside-right for unfathomable Cruyffian reasons, and narrowly survived death. In 1991, aged 43, he had a bypass operation that forced him to give up his beloved cigarettes. On the plus side, the experience encouraged one of his bizarre hobbies. “All my life I’ve watched operations, right up to brain operations,” he said. “Julio Alberto’s knee operation was beautiful, technical. I was right there watching in a doctor’s uniform.”

Months after the bypass, Barça won the first of four straight league titles. In the previous 17 years, they’d won just one. The ‘Dream Team’ also won the European Cup of 1992, and played a Cruyffian style that Barça still adhere to today. (Just don’t call it total football.)

The zenith of Cruyff’s managerial career should have been winning a World Cup with Holland. In 1993, the Dutch FA made the offer. The FA’s chairman, Jos Staatsen, later made an interesting point about the unending negotiations: he felt that Cruyff the person wanted to do it, but Cruyff the company didn’t. Cruyff was a hard and brilliant football man, but he wrongly fancied himself as a hard and brilliant businessman, and that often got in the way. Appearing on TV to explain his refusal, Cruyff bored on about money until his old team-mate Piet Keizer, sitting beside him, interrupted: “Say, Johan, you suddenly started playing with the outside of your foot. Why?”

In his last years at Barcelona, Cruyff grew ever more radical. He thought about giving a defender a pair of gloves and putting him in goal, so as to improve the passing from the back. His family managed to dissuade him. Meanwhile he was forever maddening Barça’s board.

Cruyff the manager came to a sad end. When he heard that Barça were replacing him with Bobby Robson, he reportedly smashed a chair in the office of vice-chairman, Joan Gaspart, and screamed: “God will punish you for this deed, as God has punished you before.” This seems to have been a reference to the death of a grandchild of Barça’s chairman Josep Luis Nunez. Gaspart told the story to the Dutch writer Leo Verheul, adding: “And to think that Johan doesn’t believe in God at all. Johan only believes in himself.”

Though Cruyff was then only 49, he never coached again.

The legacy

In 2003, when Barça were looking for a new manager, Cruyff gave the club a shortlist of five names, all of them Dutchmen who were in his good books. Of the five, only Frank Rijkaard was available. He was duly appointed.

Yeah, but come on, what has Johan Cruyff ever done for us?

When Johan Cruyff turned 50, in 1997, practically every newspaper and magazine in Holland published a special Johan Cruyff supplement. He was invited to hundreds of parties. A nation that hadn’t appreciated its finest son enough was saying sorry. That was the peak of Cruyff’s reputation. Dutch people told each other anecdotes about the genius who had remained an ordinary guy: Cruyff eating at the counter in an Amsterdam snackbar, Cruyff cycling past a stranger’s house and calling out, “Hi!”

He could have settled into his status as Dutch national teddy bear. Instead he tried to be godfather of Dutch football, and in the process lost much of his power and popularity.

Having been a brilliant player and brilliant manager, he became a brilliant TV pundit. People would stay home to see Cruyff as much as the match itself. He was continuing his decades-long effort to educate the Dutch in football.

Cruyff the pundit was beloved for his insights, his very personal language, and his mastery of the apparent paradox. Probably his most famous was, “Every disadvantage has its advantage”, which came as part of a lecture on how to turn your weaknesses into strengths. Or there was his warning about Italy: “Give them one chance and they’ll score two goals.”

By the time he became a pundit, his working-class Amsterdam accent was decades out of date, which added to his kitsch appeal. Without knowing it, he was a great comic actor. He also rode bizarre hobbyhorses – at one time his answer to any problem was to call for Aron Winter to be sent on – and cultivated enemies. Nobody can ever remember him saying anything nice about Louis van Gaal, in particular. Recently he has stopped appearing on Dutch TV, complaining that all sorts of “pundits” are paid to spout off even though he alone in Holland “understands football”.

But he doesn’t take the job too seriously. He admits: “When I come home from a TV analysis, my wife asks, ‘What did you say?’ and I say, ‘Even if you beat me to death….’” (that last being a Dutch phrase meaning, I have no idea).

The problem was that he wasn’t content just educating. As ever, he sought control too. One of Cruyff’s former team-mates told me that Cruyff was friendly with certain journalists, but not so much with his old team-mates. This seemed like an innocuous remark, but then this middle-aged man who had played two World Cup finals panicked and began shouting, “Don’t write that! Because Johan can get me!”

Cruyff still controlled much of Dutch football plus Barcelona. He punished those who crossed him, and rewarded his friends with jobs. In 2003, when Barça were looking for a new manager, Cruyff gave the club a shortlist of five names, all of them Dutchmen who were in his good books. Of the five, only Frank Rijkaard was available. He was duly appointed.

But 2008 was an Oedipal year: Dutch football killed its father. One evening that February, Cruyff suddenly showed up at a meeting of Ajax’s members’ council, and began to speak. He was swiftly installed by acclamation as the ailing club’s new dictator. But 17 days later he drove out of the Amsterdam ArenA again, and flew home to Barcelona. He explained he had wanted to revolutionise Ajax’s youth academy, sack loads of people, but that the club’s coach-elect Marco van Basten (Cruyff’s own footballing son) had said no. “And then I’ve got no more business at Ajax,” concluded Cruyff. His ‘fourth coming’ at the club was over.

He then lost his grip on the Dutch national team, too. Like most people, as Cruyff got older he had stopped thinking new thoughts. He continued to insist that Ajax, Holland and Barcelona play 4-3-3, just as they had in the 1970s, even though football has changed since. Nowadays players run three times as many kilometres per game as in the 1970s. When players like Dirk Kuyt or Gianluca Zambrotta can play in two positions at once, it doesn’t make sense to post a stationary winger waiting by the touchline for the ball all game.

Before Euro 2008, a group of Dutch players persuaded the coach, Marco van Basten, to abandon wingers and play 4-5-1. In the first two games of Euro 2008, a winger-less Holland thrashed Italy 3-0 and France 4-1. Some Dutch players ran nearly 12 kilometres. Cruyff then said he hoped they’d run less in future games – they were running so much only because they were out of position. When Russia then outran Holland in the quarter-final and eliminated them, another Dutch pundit, Rene van der Gijp, quipped that the Russians should have been told to run less too. Russia’s coach, the Dutchman Guus Hiddink, has replaced Cruyff as the best thinker in Dutch football: all the virtues of the ’70s game, but also a modern understanding of physical football. Whereas Cruyff is an ideologue, Hiddink is a pragmatist, and so he can adapt.

Things kept getting worse for Cruyff. Just before Christmas 2008, in a survey by his ‘own’ football weekly Voetbal International, only one percent of Dutch league players named him as their favourite football pundit. Then his arch-enemy Louis van Gaal won the Dutch title with little AZ.

Cruyff’s legacy is somewhat better preserved at Barcelona. At least Barça still post men on the wings, even if Henry and Messi aren’t really wingers. When I asked Rijkaard last season if Barça’s game was still in the Dutch tradition, he said, “Well, somewhere in the distance, but again, not really.” But the spirit of Barcelona’s free-flowing game remains Cruyffian. Josep Guardiola, who was himself discovered by Cruyff, puts it this way: Cruyff painted the chapel, and Barça’s subsequent coaches must merely restore and improve it. The most glorious team on earth today plays an updated version of Cruyffian football. Fifty years after Cruyff began talking football, that’s not a bad legacy to have.

This feature originally appeared in the July 2009 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe!