The long read: Guardiola's 16-point blueprint for dominance - his methods, management and tactics

With Guardiola settling in the Man City hot-seat, FFT's award-winning Andy Murray investigates precisely what fans can expect from the notorious perfectionist...

He’s widely regarded as the most innovative coach in Europe, and after one of football's longest courtships Pep Guardiola will finally lead Manchester City this season. So what can the Premier League expect? How does the Catalan work? Read on to examine Pep's blueprint...

He demands total control

Guardiola's rows with Bayern doctor Hans-Wilhelm Muller-Wohlfahrt ended in the latter’s resignation – after 38 years at the club

Never question Pep Guardiola’s authority. This is a man who needs to feel loved, from the boardroom to the training pitch, if he is to bring his revolution to your football club.

Though he struggled with the workload of being Barcelona’s de facto spokesman under fiery president Joan Laporta, Guardiola’s support for the man who gave him his big coaching break with the B team was ceaseless. When Sandro Rosell – a sharp political operator, whom Guardiola mistrusted – replaced Laporta in early 2010, the alienation that followed played a significant part in Pep leaving Barça at the end of 2011-12 for his New York sabbatical. The 6,000km Guardiola put between the pair was a blessed relief.

At Bayern, the rows between Guardiola and long-term doctor Hans-Wilhelm Muller-Wohlfahrt ended in the latter’s resignation (after 38 years with the club) at the continued implication that he was responsible for Die Roten’s frequent injuries.

Before his imprisonment for tax evasion, ex-Bayern president Uli Hoeness had lunch with Guardiola nearly every day, the pair swapping stories over plates of rostbratwurst sausages. Though Guardiola and Karl-Heinz Rummenigge, a confirmed Pep devotee who marvels at his coach’s talent, frequently share a coffee, the pair’s relationship cooled after the chief executive suggested during July 2015’s tour to China that the club would survive without their leader.

That said, Guardiola is aware enough not to remodel an entire squad. Rumours abounded that he wanted to ship out Gerard Pique and Dani Alves, among others, in his final Barcelona season. In the end, he fell on his own sword.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Support him, give him what he wants, or Pep walks away.

He’s tactically flexible

…and he expects the same from his players. Why? Because Guardiola has understood the most complex tactical instructions since his teens.

“Now you’re going to play as a false winger,” the former head of La Masia, Oriol Tort, told the 13-year-old with his team trailing 1-0 at half-time to minnows Carmel – not the easiest idea for a skinny central midfielder to process. However, Guardiola drifted into the vacant space between the centre circle and his winger.

“We won 3-1 and I touched the ball more in 15 minutes than in an entire half,” he wrote in his out-of-print 2001 autobiography La Meva Gent, El Meu Futbol (‘My People, My Football’). “Just by moving two paces I could radically change the game’s rhythm. Tort knows more about football than those who invented it.”

If a 13-year-old can do it…

Communication is key

Intimate with his players, he cried with youngster Pierre-Emile Hojbjerg when the midfielder lost his father to stomach cancer

Put simply, Guardiola loves talking about football. It’s a process that begins the first time he meets his players, continues throughout every training session (“He interjects all the time to correct and explain exactly what he wants from us,” recalled Dani Alves of Pep’s early days at Barcelona) and even extends to individual chats every day. Praise is effusive when merited.

Guardiola typically spends two hours per day discussing one-on-one the positional minutiae of what he demands from his players. Entirely self-taught as a player, Jerome Boateng has been the biggest beneficiary at Bayern Munich, adding brains to his prodigious centre-back brawn, while Philipp Lahm still spends 15 minutes after every training session talking in minute detail about midfield play, his hands a blur of explanatory signals. For more instinctive players such as Franck Ribery, less is more.

“Pep doesn’t just give you orders,” said Gerard Pique. “He also explains why.”

He knows his players intimately. He cried with youngster Pierre-Emile Hojbjerg when the midfielder lost his father to stomach cancer in April 2014. He wants a maximum of 20 players in a first-team squad because he hates telling anyone that they have failed to make the 18-man matchday squad.

He varies what he says, too, not through any kind of psychological plan but merely to express exactly what he is feeling inside. “Guys, you’re all greats,” he told his Barcelona players before 2010’s title-decider against Villarreal, which came two days after Champions League semi-final defeat to Jose Mourinho’s Inter Milan. “I just want to tell you one thing. If we go out there and lose, and the league escapes us, don’t worry.” They won. 4-0.

He builds around a conductor

Johan Cruyff used to tell me that if I was fouled, it was my own fault because I’d held onto the ball too long

At Barcelona it was Sergio Busquets; occasionally Xavi or Andres Iniesta. For Bayern, Thiago Alcantara, Xabi Alonso and Philipp Lahm have performed the role. In every game, Guardiola picks his avatar – the player whose job is to keep the play moving, as he did.

In his 2001 autobiography he wrote: “[His former Barça boss Johan] Cruyff used to tell me that if I was fouled, it was my own fault because I’d held onto [the ball] too long; I had to let it go much before.”

Yet Guardiola also demands what he calls “players with a pause”. Capable of holding onto the ball for half a second longer than your average midfield clogger, they lull the opposition into a positional error. He did it better than most himself. “I tried to trick the opposition into thinking I’d pass it wide again,” he says in 2014’s Pep Confidential, Marti Perarnau’s account of Guardiola’s first season at Bayern, “and then – boom! – I’d split them with an inside pass to a striker.”

It was this understanding that prompted his somewhat surprising decision to play Lahm in central midfield instead of his customary full-back position.

“He is super-intelligent,” Guardiola said of his elegant Bayern captain. “He understands the game brilliantly; knows when to come inside or stay wide. The guy is f**king exceptional.”

In short, Lahm became his organising midfielder, the fulcrum around which the whole team moves. Only the most intelligent players can pull off this difficult role, which demands one player that does everything that both holding midfielders do – the ball retention, positioning and intercepting – in the 4-2-3-1 setup that Guardiola seldom uses because it’s not attacking enough.

When he really wanted total domination of the ball, he would choose his former Barcelona protégé Thiago as conductor, the player he demanded oder nichts (“or no one”) when he took over from Jupp Heynckes in 2013.

“The basis is there: maintaining possession and playing the ball out from the back,” Thiago explains to FourFourTwo, comparing Guardiola’s two teams. “Of course, every team is different, but any Pep team is always going to be based on ball retention. It’s his mentality.”

32 mins

Talk of Guardiola’s intensity is nothing new. He dedicates nearly every waking hour to planning his training sessions, coming up with tactical schemes and studying potential signings and upcoming opponents. Only by completely immersing himself in how his team will play, how his players will interact on the pitch, does he feel able to perform at his best.

His personal assistant Manel Estiarte calls it ‘The Law of 32 Minutes’. It’s the period of time Guardiola can disconnect from football before thoughts return to the beautiful game. Sometimes he has to be told to go out for a meal, or go home to play with his children Maria, Marius and Valentina. Then, after half an hour, he will either shut himself back in his office or his mind will drift.

Estiarte expounds his law in Pep Confidential, saying: “He starts staring at the ceiling, and although he’s nodding as if he’s listening, he’s probably thinking about the opposition left-back.”

Defensive structure is paramount

Pep’s free-flowing philosophy may be what draws in the casual observer, but he dedicates more training sessions to defensive organisation than anything else. It shows: before the 2015-16 winter break Bayern had conceded only 49 goals in 85 Bundesliga games since he arrived, keeping 50 clean sheets.

Attack is based on innate talent, defence is about the work you put into it. Defensive strategy is absolutely essential if I want to attack a lot

“Attack is more based on innate talent,” he once said. “Defence is about the work you put into it. Defensive strategy is absolutely essential if I want to attack a lot.”

Bought by Bayern from Athletic Bilbao, Javi Martinez virtually had to learn how to walk again, ditching the man-marking system he knew in the Basque Country for Guardiola’s more fluid zonal system. For six months, the Sabener Strasse training ground echoed with shouts (always in Spanish) of “Javi, go forwards!”; “No, not now, Javi!!”; “Javi, look at Dante!”

Yet the sessions worked. Martinez was transformed from prosaic midfield anchor into one of the best defenders in Europe.

Guardiola has shown me 200 videos and taught me concepts: when to move out with the ball, when to mark, where to position myself. He’s incredible

“We’ve done so much tactical work,” says Martinez. “He has shown me 200 videos and taught me concepts: when to move out with the ball, when to mark, where to position myself. He has an idea and knows how to teach it every session. He’s incredible.”

What Guardiola wants above all else is a defence that moves as one – a self-contained organism that suffocates opposition attacks by pressing high. If the centre-back presses, the midfield conductor drops in behind to cover; similarly, the winger covers his full-back. On average, Pep's Bayern would defend seven metres further up the pitch than they did under Heynckes. It’s a proactive sort of defending that can be achieved only by religious practice that begins against no opposition, to first learn the necessary movements.

But Guardiola’s defensive strategy doesn’t end when his team have the ball. Moving gradually up the pitch, to give the conductor full orchestral scope, Guardiola wants his team to complete 15 passes, the theory being that his players retain their shape, while destabilising their opponents. It is a defensive tactic as much as it is a transition to attack via gradual strangulation, because done effectively it prevents the chasing opposition from counter-attacking.

What he can’t abide, however, is when these 15 passes don’t go anywhere - which is why he hates tiki-taka...

READ ON: Pep's hate for tiki-taka and his nutrition obsession

He hates tiki-taka

Yes, really. The concept most associated with his blueprint is the former Barcelona coach’s biggest bugbear.

Tiki-taka is a load of s**t - passing for the sake of passing. I won't allow my brilliant players to fall for all that rubbish

“Tiki-taka is a load of s**t – a made-up term,” he has often repeated of the initially pejorative phrase first coined by pundit Javier Clemente after watching Spain’s sterile possession game against Tunisia at the 2006 World Cup. “It means passing the ball for the sake of passing, with no real aim or aggression – nothing. I will not allow my brilliant players to fall for all that rubbish.”

Many seek to emulate Pep’s style, but see possession as the objective in itself, turning an attacking philosophy based around constant movement and freedom into a stodgy, passive hope of eventually reaching the opposition box. Teams copy it, but badly, failing to appreciate the hours of work that have gone into creating the space to attack.

At Barcelona, Guardiola’s strategy was long entrenched. Coming to English football, he will have to adapt to his new players and coach them constantly in the first six months for them to fully grasp the system’s complexity, in the same way he did at Bayern. Maximum intensity is demanded at all times, because, Guardiola believes, that is the only way to train his players’ muscles in the football-specific movements that define his attacking remit.

CLASS: Bayern Munich passing masterclass in training.March 9, 2016

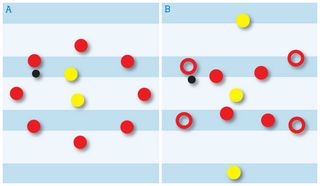

The cornerstone is the rondo (Diagram A), a piggy-in-the-middle drill that begins every training session. The ball flies around at speed, which helps to sharpen technique in tight areas, with the goal being to reach 30 touches, the eight players counting out loud as they go. If you lose the ball, you go in the middle as punishment.

A variation on the rondo adds an extra element. The drill is 4v4 with another three ‘neutral’ players who play for whichever side has possession, making the game effectively 7v4 (Diagram B). Crucially, however, as soon as possession is turned over, the team who lost the ball can then immediately counter-press to win it back. The effect is two-fold: it establishes the importance of being alive to the counter-press having just lost possession, and the team with the ball learn how to position themselves and engineer space.

“The secret is to overload one side of the pitch so the opponent must tilt its own defence to cope,” Guardiola says in Pep Confidential. “When you’ve done that, we attack and score from the other side. That’s why you have to pass the ball with a clear intention. Draw in the opponent, then hit them with the sucker punch.”

To reach that point, however, players must develop their fitness levels. Pre-season double sessions were the norm at Bayern – by the beginning of October in 2013-14, Pep’s first season with the club, Die Roten had done 100 sessions – and everything happens with a ball. Just running is pointless.

“We train with maximum intensity,” he has said. “Even the rondos: it’s with 100% effort or you don’t do them at all. If the players don’t like them then they are welcome to go mountain running, but in that case we’ll never reach our potential.”

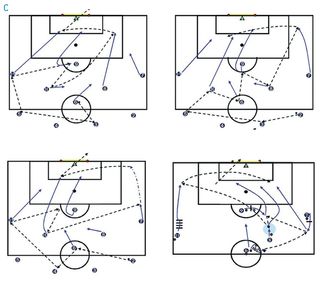

Circuit sessions with fitness coach Lorenzo Buenaventura are constant in the early days. Lesson plans from Guardiola’s 2007-08 title-winning season as Barça B coach are available online. The complexity of the 40-minute circuits is mind-blowing, arrows flying everywhere (Diagram C) – jumps over hurdles, in and out of cones, followed by shots at goal.

“It has been difficult,” recalled Lahm at the end of Guardiola’s first season at Bayern. “But it was also necessary after we had won everything. Pep wanted to teach us something new.”

Weeks after he joined the club, Guardiola’s Bayern scored from a remarkable 94-pass move against Manchester City in the Champions League. Premier League defences, you have been warned.

He’s a tactical innovator

Guardiola watches the opposition’s previous six matches, plus targeted highlights provided by his head of analysis

Guardiola is swift to dismiss formations as “meaningless” and “nothing but telephone numbers”, partly explaining the fluidity and flexibility with which he alters a team’s structure.

Born from meticulous analysis building up to a game – Guardiola watches the opposition’s previous six matches, plus targeted highlights provided by head of analysis Carles Planchart – he’ll get a ‘Eureka moment’ that crystallises how his team will win. “It’s the moment that my job becomes truly meaningful,” he has said.

Using Lionel Messi as a false nine for only the second time, in the May 2009 Clasico, is his most famous innovation. The night before the match, he called Messi into his Camp Nou office at 10.30pm to show the Flea the exact areas he could exploit.

Guardiola’s use of a back three stems from his desire to achieve numerical superiority. At Barça, Gerard Pique brought the ball out from the back to blur the lines between defence and midfield; at Bayern, that job frequently fell to Jerome Boateng.

“I’m no innovator,” Guardiola has said. “I’m an ideas thief.” It’s true the influence of Cruyff’s Barcelona and Louis van Gaal’s Ajax are undeniable (Pep himself wrote: “They were capable of perfection – they gave football lessons to everyone”), but few have the stones to employ such radical concepts in huge games.

Interiores are his key performers

Whether it’s Barcelona’s double Champions League-winning 4-3-3 or Bayern’s evolution on a theme, one constant remains in Guardiola’s arsenal: the need to deliver the ball to his best players, in as much space as possible, in the inside channels.

In Catalonia it was Xavi and Iniesta, in Bavaria Arjen Robben and Franck Ribery. The first two are classic Spanish interiores: central midfielders who operate in the channel between full-back and centre-back, and load the Messi bullets. In contrast, Robben and Ribery are wingers, who cut inside to occupy the interior space. In Germany they call it halbraum, or ‘half-spaces’.

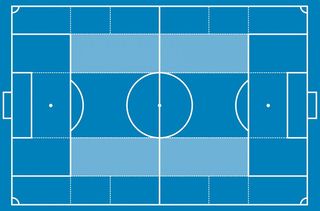

To achieve this, Guardiola has a training pitch marked out very specifically for practice matches (see below): five vertical and four crossfield sections, of which two are subdivided in the wide areas. The two inside channels (shaded pale blue) are where he wants his best players in possession – Xavi and Iniesta to assist, Robben and Ribery to score – because they fall between all lines of the opponent’s defensive structure.

These aren’t mere guidelines or ideal scenarios. There are rules: no more than three players in any horizontal zone; no more than two players in any vertical zone.

For example, if Ribery cuts in from the left wing, left-back David Alaba should overlap. To cover Alaba, a central midfielder should drop to the left. If a rule is broken in training, Guardiola interjects, because it denies his most important players space.

“This happens every f**king game!” he screamed during a training session in Doha in January 2014, the YouTube video of which went viral. You wouldn’t like Pep when he’s angry.

Nutrition is a serious business

To be an elite footballer, you need to eat like one. Hardly revolutionary, but when Guardiola saw pastries and cakes laid out for the team during his first pre-season at Bayern, he called for a nutritionist.

Eating the meal provided in the players’ lounge is compulsory. When only four players did so after a Bundesliga game against Nuremberg in August 2013, Guardiola spat at his squad: “I won’t ask again. You must eat within an hour of the match and since you’re all professionals playing at the highest level I trust that you will do it from now on.”

There’s no room for romanticism

All the hours spent studying videos, talking to his players and analysing every detail is pointless if he doesn’t win

Don’t ever confuse Pep Guardiola for a style-over-substance aesthete. Unsurprisingly for someone who has hoarded 21 trophies in eight seasons as a top-flight coach, he wants to win.

At the centre of everything, however, is the desire to win with style. Ultimately, Guardiola chose Bayern as his next club after Barcelona – where he wants to one day return, to head up La Masia – because he wanted to prove he could advance on the ‘perfection’ that former coach Jupp Heynckes had left. Before joining Bayern, he researched every Bundesliga club to understand how they counter-attacked, but all the hours spent studying videos, talking to his players and analysing every detail is pointless if he doesn’t win.

Thiago agrees. “It’s a great mix: you know how he wants you to play and how to combine that with your own qualities. That’s how good results follow. The players will end up drained by Pep. He’s so intense, he’ll exhaust us.”

READ ON: Guardiola's tactical tinkers, his fixation with routine and the third man

The third man is crucial

The other way Guardiola provides space for his interiores is by maintaining width. If play develops down the right wing, the opposite wideman must hug the left-hand touchline to avoid overpopulating central midfield and denying Iniesta, Robben or Ribery the space to play.

“Guys who are supposed to play on the right are not allowed to cross to the left, and on the left you’re not allowed to cross to the right,” former Barcelona forward Thierry Henry recalled on Sky Sports’ Monday Night Football.

Pep said ‘My job is to bring you to the last third; your job is to finish it’. The last third was freedom for us. But when Pep has a plan, you respect it

It’s what Guardiola calls “the third man” and is an extension of a rondo variation to escape counter-pressing – wait for the moment to switch the play to the opposite wing and change the reference point of the attack. It’s why Xabi Alonso, with his range of passing, has become so vital to the Bayern system, whether he’s in defence or his natural holding midfield role.

It’s a system Pep learned as part of Cruyff’s Dream Team. In his autobiography, Guardiola describes the play as “pels extrems i amb els extrems”, a wonderful Catalan phrase that means “on the limit and with the wingers”.

There is scope for improvisation, however. Once in the final third, Guardiola’s players are allowed total freedom to move as they see fit to score. Messi could seek space. Ditto Thomas Muller, that ‘space investigator’, or Robert Lewandowski. Henry added: “He used to say: ‘My job is to bring you to the last third; your job is to finish it’. The last third was freedom for us. But if you don’t do what he is asking you to do, you're going to be in trouble. When Pep has a plan, respect his plan.”

The Frenchman knows this from experience. In 2008, frustrated at not touching the ball much in the first half of a 5-2 Champions League win in Portugal against Sporting, Henry vacated his left-wing berth to look for it.

“I could hear him being upset on the side, but I still went there – I didn’t really care,” admitted Henry. “I scored a goal, and at half-time he took me off.”

Every player has a job and Pep’s instructions must be followed. To the letter.

You have to buy into Pep

Samuel Eto’o, Zlatan Ibrahimovic and Mario Mandzukic have all lasted just one season under Guardiola

Much is made of Pep’s Barça-ball style, yet he clearly adapted to Bayern’s strengths out wide, encouraging crossfield balls for Robben and Ribery. “I’m not some kind of Taliban; I’m not totally inflexible,” he says in Pep Confidential. “I’m happy to evolve. But please don’t ask me to do something I don’t believe in.” And if you don’t do what he believes in, you’ll find yourself discarded.

Guardiola will not bend over backwards to accommodate a player who won’t adapt to his requirements in the same way that Pep adapts for the team. Javi Martinez has evolved to great effect; ditto captain Lahm and star man Ribery. “I love you, Pep,” the French winger told him in 2014. “I’m just a street kid, but you will always be in my heart.”

Yet he struggles to manage players with a singularity of personality. Samuel Eto’o, Zlatan Ibrahimovic and Mario Mandzukic have all lasted just one season under Guardiola. The latter’s sulking when out of the team was a particular annoyance to the coach. It’s no coincidence that these three are driven centre-forwards with more than a dash of ego, who define themselves by goals.

“Guardiola disappointed me because he didn’t treat me with respect; it was twice as good when Jupp Heynckes was there,” said Mandzukic, who joined Atletico Madrid at the end of the Spaniard’s first season at the Allianz Arena. Eto’o and Ibra have also cited a lack of respect.

Guardiola’s preference for a false nine may not help, but Robert Lewandowski’s 48 goals in his first 75 Bayern games is proof that if you’re willing to adapt, Pep will change his tactics for you.

On the day Douglas Costa arrived at Bayern from Shakhtar Donetsk, his new coach asked him: “Are you ready to open your mind and learn how to play football?” Frequently used in an unfamiliar left-wing position, the Brazilian had scored five goals and assisted a further 12 by the winter break. He’d learned well. One wonders whether Premier League stars, used to prioritising physique over tactical mastery, will be able to follow suit.

He’s a risk-taker

Pep would rather die going forward than stay alive defending

Guardiola’s belief in his own ideas, however well founded, can be his biggest downfall.When Guardiola introduced 3-4-3 to Barcelona in 2011/12, with mixed results, he wanted to challenge a team that had already won everything. Unfamiliar with the system, Los Cules lost the league to Jose Mourinho’s Real Madrid and exited the Champions League to Chelsea in the last four.

When presented with two possible options, he always chooses the more attacking one (“Pep would rather die going forward than stay alive defending,” Thierry Henry once said of his former coach). There is much to admire in this. But in Bayern’s biggest games under Guardiola, the coach’s master plan went badly wrong.

First, there was the 2014 Champions League semi-final. Trailing 1-0 from the first leg at Real Madrid, a 4-2-3-1-shaped Bayern side surrended midfield superiority of the ball in favour of four out-and-out-attackers (Robben, Ribery and Thomas Muller pushed high, with Mandzukic as centre-forward) and lost 4-0 at home.

Twelve months on, question marks were again raised over Guardiola’s daring after he selected a back three (Boateng, Rafinha, Medhi Benatia) to face Barcelona’s fearsome attacking trident of Messi, Neymar and Luis Suarez. “Pep Guardiola is probably the only coach in world football who would do this away at the Nou Camp,” said commentator Gary Neville. “Everyone else would be thinking: ‘How do we double-up on them, or protect, or screen?’”

After 20 minutes of a Barça barrage, he had to change to a back four. Bayern lost 3-0, and the tie was effectively over. So often does the risk-reward football work, he possibly gets too clever for his own good. This could see him struggle in the Premier League furnace.

He’s obsessed with routine

Half-time is the one and only occasion that Guardiola enters the dressing room before or during the game

Nothing is left to chance. The same long-established process is followed religiously in preparation for each fixture. Such painstaking preparation serves to calm the 44-year-old coach’s pre-game nerves.

Two days before every match, Guardiola and his assistant, Domenec Torrent, will analyse the data and videos provided on the next opponents, shutting themselves in their respective training ground offices so that their thoughts are not contaminated by each other. Guardiola then plans. Alone. For hours. He does stop occasionally, to run ideas by his son Marius and eldest daughter Maria, who share their father’s love of tactics.

There are three pre-game team talks. The first, at training the day before the match, will outline the video analysis results, with the session that follows focusing on how they’re to be countered. The second, on the morning of the game, details defensive and attacking set-pieces. Finally, two hours before kick-off, Guardiola’s focus will be entirely on attacking strategy and motivation.

Perhaps surprisingly, he never enters the team dressing room before the game, believing it to be the players’ domain.

There is a routine to his in-game life, too, all hand signals and shouts of encouragement; meanwhile up in the stands, head of analysis Carles Planchart will send images of specific moves down to Torrent’s iPad on the bench. Half-time is the one and only occassion that Guardiola enters the dressing room before or during the game.

Post-match is when he is at his most relaxed. Still unable to eat properly – a matchday nerves hangover – he’s chatty, amiable and will wander round the players’ lounge talking about what he’s just witnessed to anyone who’ll listen. He has been known, as the adrenaline exits his system, to steal the odd bit of food from his players’ plates, before gorging himself later that evening. Then it’s back to the training pitch and more hours of preparation.

He’s his own biggest critic

All I do is look at the footage of our opponents. Then try to work out how to demolish them

“Pep will never be satisfied,” his midfield metronome Thiago once said. “He’ll never enjoy football because he’s always looking for what has gone wrong in order to correct it. Pep is never happy. He’s a perfectionist.”

Maybe it’s because losing is something that happens so rarely to Guardiola, but nowhere does the weight of defeat fall heavier than on his own shoulders.

The 4-0 loss to Real Madrid is his biggest regret in football, because he changed his mind from employing a back three that would make them capable of overloading Los Blancos’ midfield to a front four who were effectively isolated. Alongside his backroom staff, he was still going over tapes in his office at 2am.

Rest assured, in the Premier League the critics will come. English football tends to have an inherent mistrust of the new. But they won’t be more critical than Pep is of himself.

It’s the product of the hours of planning that came before. If you’re as obsessed with football as Pep Guardiola is, you’d be the same. “All I do is look at the footage of our opponents,” he says, “and then try to work out how to demolish them.”

READ ON: Pep's backroom staff, the challenges he faces in England and an interview with the man who got up close

Meet Pep’s Entourage

Coming together at Barcelona, Guardiola’s now-established team followed him to Bavaria and now to Manchester. Meet the men behind the manager.

Domenec Torrent Assistant coach

At Guardiola’s side since 2007, Torrent has evolved from doing scouting for Barcelona B to becoming assistant coach at Bayern Munich. Torrent stayed in the Catalan capital a year longer than Guardiola, who eventually persuaded him to move to Germany as his second-in-command.

Never without an iPad on the bench, Torrent is credited with convincing Guardiola to play erstwhile full-back Philipp Lahm as a central midfielder for the first time in an official game (the 2013 UEFA Super Cup against Chelsea).

“All the pieces fell together with that decision,” Guardiola later said. “If we win anything, it’s because of that.”

Manel Estiarte Personal assistant

One of the finest water polo players of all time (he’s known as the sport’s Maradona), Estiarte met Guardiola during the 1992 Barcelona Olympics and they’ve been firm friends ever since. He was head of external relations at Barça, and joined Bayern Munich as Pep’s personal assistant.

Before the shootout in the 2013 UEFA Super Cup, Guardiola used Estiarte’s water polo prowess to inspire victory over Jose Mourinho’s Chelsea. “He’s the best penalty-taker in the world,” Pep told his players. “I’ve learned two things from Manel: don’t change your mind, and believe you’re going to score.” No Bayern player missed.

Lorenzo Buenaventura Fitness coach

Without Buenaventura’s training ground exercises, the Guardiola coaching model would fall apart.

Buenaventura is a disciple of Paco Seirul-lo, the fitness coach for Johan Cruyff’s Barcelona, who tutored Guardiola in the late ’80s, and he passionately shares the Bayern boss’ belief that all training exercises must be carried out with a ball, at maximum intensity, for their ceaseless attacking model to properly function.

In short, Buenaventura is the brains behind training – which, in many ways, makes him the brains behind the entire Guardiola backroom operation.

Carles Planchart Head of analysis

Planchart arrived in Munich at the same time as Torrent, providing the Bundesliga champions with in-game analysis of Bayern’s patterns of play from the stands to Torrent’s iPad. Guardiola, Torrent and Planchart then feed this into the half-time team talk.

But it is his forensic dossiers on upcoming opponents that Guardiola appreciates most. Frequently working two weeks ahead of himself, Planchart and his team review the opposition’s previous six matches, with 50-60 bite-size moves adding further detail.

Planchart’s work is available the day after the previous game and shapes training for the following week.

“He’s often a sarcastic joker”

Meet Marti Perarnau, the author who got up close and personal with Pep at Bayern

The special quality he has is in how he interprets football – he understands it like no one else

You’ve spent more time with Guardiola than anyone outside his closest circle. What’s he like?

There’s very little that is special about him. He’s just very normal and unassuming. As a coach, he’s very famous, and some of what you see publically is to protect himself and his family.

The perception is that because he’s such a great coach, there must be something different to him, but that’s not really the case. He’s very humble and always deals with problems personally. The special quality he has is in how he interprets football – he understands it like no one else.

Does he ever stop thinking about the sport?

He does, but the majority of his day-to-day life is dedicated to football. He’s obsessive in the sense that he constantly applies theories and things he reads to football in order to become better. His mentality is to learn. He likes knowing new things. It’s why he went from Barcelona to New York, to Munich and next, to England.

He jokes about only wanting to see the restaurants, but it is all to learn. He meets new people, learns about new cultures and how to then incorporate those cultures into his coaching. That is why he went to the concentration camp at Dachau. It will be the same case in England, too. He’s a better coach now than before he went to work in Germany because of it.

How does he deal with defeats?

They affect him more than other coaches, because he so rarely loses matches. He blamed himself for the Champions League semi-final defeat to Real Madrid in 2014. He really hurt – it took him days to get over it. He’s always with his coaches analysing the ‘why?’. He tries not to get too carried away with victories, nor too down after tough defeats. There’s no depression there.

He’s a real joker with his players. He’s always tapping players on the arse, or giving them a playful slap around the head

What is his sense of humour like? Does he have one?

He’s a real joker with his players. At the beginning they didn’t understand his ways at Bayern. He can be quite sarcastic and they thought he was being serious. He’s always tapping players on the arse, or giving them a playful slap around the head. It shocked them a bit. Pep’s really tactile, with hugs, even kisses. He is very Latin in that sense.

Will the press be a problem?

He doesn’t give one-on-one interviews, apart from obligatory ones for rights holders, but you can ask him anything at a press conference. Sections of the German press didn’t warm to him, but that’s life. You’ve got four chances to speak to him – before and after matches, assuming there are two per week – and he will talk without limits. He loves talking about football, his philosophy and his team.

How was your year living so close to him?

I didn’t know him before Munich. It was amazing to be so close to such a brilliant coach teaching a team a totally new way. They’re masters at it now. I had doubts at the beginning, but Lahm, Robben and Ribery want to learn. Trying to figure out what Pep is trying to do wasn’t easy for them – imagine what it was like for me!

We do things differently here

Pep may have conquered all in Spain and Germany so far, but English football presents some unique challenges

“Football, football, football”

It took just three months for Jurgen Klopp to understand what the English game is all about: football, and lots of it. Even a manager as well prepared as the German didn’t realise there are replays in the FA Cup and two legs in the League Cup semi-final. Guardiola will be spending more time pitchside than ever before.

It’s all in the mind

Guardiola, meet Pardiola. The Premier League may have lost Alex Ferguson, but there’s no shortage of mind-games masters, from Alan Pardew to Pep's old nemesis Jose Mourinho. Don’t get drawn in, Pep – that’s what they want.

Beware of the media

Louis van Gaal is as experienced as they come but he still allowed the English media to get to him, even to the point of storming out of a press conference. As a manager who craved increased training-ground privacy at Barcelona and Bayern, and doesn’t do one-on-one interviews, Pep may find there’s no place to hide in the Premier League goldfish bowl.

A winter of discontent

Apart from Israel, every UEFA country outside Britain has a winter break, and it’s something Guardiola will be accustomed to from his time in Spain (where they break for two weeks) and Germany (four). Sorry, señor, but Leicester’s nothing like Qatar.

There are no easy games, Jeff

The cliché has had a rebirth this season, with a new TV deal giving the Premier League’s smaller clubs budgets comparable to only the biggest teams in mainland Europe. “After we beat Arsenal, Liverpool and Man City away, people are expecting us to beat Norwich 6-0,” explained West Ham boss Slaven Bilic in September. “It doesn’t happen like that.” Indeed it doesn’t – they drew 2-2. There are far fewer whipping boys in England than Spain and Germany.

Stoke on a wet and windy Tuesday

It was Andy Gray who suggested that, as great as Guardiola’s Barça were, they’d struggle on a wet, windy night in the Potteries. Stoke may be undergoing an image change, but a visit to the Premier League’s coldest and second-noisiest ground (according to a recent study) remains the acid test of a team’s title credentials. Can Pep pass it?

This cover feature first appeared in the March 2016 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe!

Andrew Murray is a freelance journalist, who regularly contributes to both the FourFourTwo magazine and website. Formerly a senior staff writer at FFT and a fluent Spanish speaker, he has interviewed major names such as Virgil van Dijk, Mohamed Salah, Sergio Aguero and Xavi. He was also named PPA New Consumer Journalist of the Year 2015.