Meet Archibald Leitch: The man who invented the football stadium

He bounced back from disaster to design and build dozens of our most famous grounds, but who was Archibald Leitch? His biographer (and renowned football architecture historian) Simon Inglis explains all...

Be honest. The football ground you go to most often, the stand you sit in: do you know who designed it? The name of the architects?

Don’t worry if you haven’t a clue. You’re not alone. You go for the football, for your team, for the craic – not to become an expert in stadium design or construction.

No one should, therefore, be surprised to learn that when Archibald Leitch died in April 1939, two days short of his 74th birthday, there was not a single obituary in any newspaper. Not so much as a news item.

Even in the architectural and engineering journals that you’d think would have taken a close interest in the stadium business – as they do today – there was just one brief entry. It appeared in the Journal of the Institute of Mechanical Engineers, the professional body to which Archie belonged, and it all it said was that Leitch had been a ‘consulting engineer and a factory architect’. No mention of which factories, and no mention at all of football grounds.

Had you gone to a Football League match in April 1939 you’d have had roughly a one in three chance of either standing on a terrace or sitting in a stand designed by Archibald Leitch’s company

No mention despite the fact that, had you gone to a Football League match in April 1939, you’d have had roughly a one in three chance of either standing on a terrace or sitting in a stand designed by Archibald Leitch’s company. At his peak in the 1920s, 16 out of the 22 clubs in the First Division had hired Archie at one time or another.

Between 1900 and 1939 his client list included Manchester United, Liverpool, Everton, Blackburn, Tottenham, Arsenal, Chelsea, Fulham, Crystal Palace, Millwall, Charlton, Southampton, Portsmouth, Aston Villa, Wolves, Derby, Sunderland, Middlesbrough, Huddersfield, both Sheffield clubs and both Bradford clubs (City and Bradford Park Avenue).

FEATURE Simon Inglis on the early history of football stadiums

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

In his native Scotland Leitch worked at Rangers, Hearts, Dundee, Kilmarnock, Hamilton and at Hampden Park.

Other commissions included Windsor Park in Belfast, Dalymount Park in Dublin, plus a stand at Twickenham and a complete greyhound and speedway stadium at West Ham, where in the early 1930s there was a doomed attempt to establish a Football League club (Thames AFC, not to be confused with the turn-of-the-century Thames Ironworks who became West Ham United).

No other firm of architects or engineers, before or since, has clocked up such a client base in British sport.

Learning the ropes

Until the late 20th century there were very few architects who bothered with football. Leitch cornered the market

How did he manage it? Firstly, as a factory architect Leitch was used to building functional structures quickly and cheaply – just what budget-conscious football clubs wanted. Secondly, Leitch himself was, as all good architects need to be, a great salesmen, and one who clearly loved football. (That he was also an active freemason undoubtedly helped at certain clubs.)

But thirdly, and most tellingly, until the late 20th century there were very few architects who bothered with football. Leitch cornered the market. He was a safe pair of hands.

And yet how differently it might have worked out.

Back at the turn of the century, newly set up on his own account as a ‘consulting engineer and factory architect’ in his native Glasgow, and already with several factory designs under his belt, Leitch’s first major football commission was to design a new stadium for Rangers, the club he supported.

Designing factories was one thing: factories had been around for decades. Building a football ground for 80,000 spectators in the early 1900s was quite another challenge. There were few precedents. Most football grounds of the period just sort of grew, stand by stand, terrace by terrace. At best, a would-be stand designer could pick up a few design tips from theatres and music halls. They might also learn a thing or two from the Colosseum and other classical ruins.

Otherwise, it was a case of swotting up on the geometrical basics (sightlines and so on), addressing the engineering requirements (loadings, stresses, materials etc), and hoping that things worked out.

In Leitch’s case they did not work out.

Bouncing back from disaster

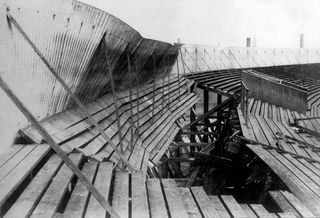

On the first occasion his newly completed Ibrox Park was tested by a capacity crowd, a short section of timber terracing gave way, sending 25 fans to their deaths

On the first occasion his newly completed Ibrox Park was tested by a capacity crowd – for Scotland’s match against the Auld Enemy on 5 April 1902 – a short section of timber terracing behind one of the goals gave way, sending 25 fans to their deaths.

Archie witnessed the disaster at first hand. What should have been the proudest day of his professional life turned into an designer’s worst nightmare. A system failure… and a tragedy.

It was said of the engineer Sir Thomas Bouch that he died ‘a broken man’ after the collapse of his recently completed Tay Bridge in Dundee in 1879. In 1902 Archie faced similar angst. Even though he escaped official censure after an uncomfortable public enquiry, it seemed unlikely he’d work in football again, especially after Rangers hired another consulting engineer to undertake a rethink.

But Leitch was no quitter. If nothing else he had shown while giving evidence that he was a man of confidence, and even wit. (Then, as now, you couldn’t get on in the boardrooms of football clubs without enjoying a drink or a joke.) So first he persuaded Rangers to take him back on.

Then he did what any decent designer would do in the circumstances. He went back to the drawing board.

Redesigning the terrace

Instead of the timber posts and rails that had sufficed to form crush barriers, Leitch designed a tubular steel barrier that could be bolted onto steel rails running under the concrete

The result of his deliberations would be made public at two grounds, both in 1905: Fulham’s Craven Cottage and Chelsea’s Stamford Bridge.

At both, Leitch built a new form of football terrace. Designed to overcome all the weaknesses exposed at Ibrox, where spectators stood on timber boards laid on an iron framework, the improved Leitch terrace was built on a bank of earth (or in certain areas the spoil from coal mines).

Each terrace step and tread was measured. To create more manageable pens, vertical and lateral aisles were positioned at regular intervals, each aisle being sunken to dissuade fans from standing in them.

Instead of the timber posts and rails that had, until that point, sufficed to form crush barriers, Leitch designed a tubular steel barrier that could be bolted onto steel rails running under the concrete, to add strength.

So convinced was Leitch of this solution that in 1906 he took out a patent, entitled ‘an improved method of constructing the terracing and accessories thereof in football and other sports grounds’.

Leaning on Archie

The wonderful Johnny Haynes Stand at Craven Cottage, and its adjoining pavilion, both built in 1905, are listed Grade II and have been sensitively restored by Fulham

Little did I know that when I first stood on the Holte End at Villa Park in 1966 I was standing on just such a terrace, spending many an hour thereafter leaning against a patented Leitch barrier. As did millions of other terrace fans, generation after generation.

Nor, at that time, did I realise that the same man had been responsible for designing the magnificent Trinity Road Stand at Villa Park. In fact, I strongly believe that it was this building, completed in 1924, that inspired me to become an historian of football architecture (or ‘anorak’ as some would have it).

Since my biography of Leitch was published, the confirmed list of his clients has continued to grow. It now appears that he worked at Chesterfield’s Saltergate, and, as many had suspected, that after his death his company also designed the Mayflower Stand at Plymouth’s Home Park in the early 1950s. More on this – the Leitch company’s last commission before it was wound up in about 1956 – can be read in Russell Moore’s new history Home Park, a Pictorial History.

As for Archie’s legacy, much of his work has long gone, my beloved Trinity Road Stand included (in 2000). This was largely as a result of the Taylor Report into the Hillsborough disaster of 1989, which took place on a Leitch terrace that had been modified with fateful consequences.

Two Leitch stands look likely to survive. The wonderful Johnny Haynes Stand at Craven Cottage, and its adjoining pavilion (‘the Cottage’), both built in 1905, are listed Grade II and have been sensitively restored by Fulham. Full marks to them.

Also listed and well preserved, albeit having been extended, is Archie’s South Stand at Ibrox, completed in 1929 – while another Leitch survivor, one of his more basic models, is the main stand at Dundee, dating from 1922.

Leitch lingers in Liverpool

Two short Leitch barriers can now be seen at the National Football Museum in Manchester and the Scottish Football Museum at Hampden Park

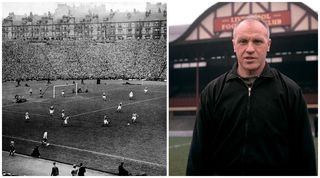

Elsewhere the concrete core of Leitch’s main stand at Anfield, built in 1906, lives on remarkably, buried deep within the vast new stand being built around it this year.

Across Stanley Park, two others Leitch stands survive at Goodison Park: the Bullens Road Stand (1926) and Gwladys Road (1938).

Neither may be around for much longer, such is Everton’s need to rebuild. The same can be said of the East Stand at Tottenham (due for the chop next year), and the main stand at Crystal Palace (which is in any case much altered). Two stands at Portsmouth and Hearts are also currently on borrowed time.

As for Leitch terraces, the last complete surviving examples in England were at Saltergate. Just before the ground was demolished in 2010, I contacted Chesterfield to see if any of the barriers might be saved. Again, full credit to the club, they agreed, the result of which is that two short Leitch barriers can now be seen at the National Football Museum in Manchester and the Scottish Football Museum at Hampden Park – appropriately enough, for Hampden boasted by far the largest number of Leitch barriers ever seen in one place, managing to hold 149,000 for Scotland vs England in 1937.

So Archie has not been forgotten after all. And nor will the architects and engineers of today. For even if most fans don’t know who designed their favourite stand or stadium, you can be sure that the information is out there somewhere, on a website, in a magazine, in a journal, in a club programme.

Backed by big corporations and marketing, conferences and exhibitions, today’s stadium and arena industry thrives.

What would Archie say? No question – he would be delighted. And fascinated. But perhaps not best pleased when he saw what had happened to his beloved Rangers...

ALSO BY SIMON INGLIS A brief history of football grounds

Simon Inglis is the author of a number of books on football history, architecture and sporting heritage. Engineering Archie, his biography of Archibald Leitch, was published in 2005 and is now out of print, but there are plans to bring out a second edition. For details see www.playedinbritain.co.uk

#FFT100STADIUMS The 100 Best Stadiums in the World: list and features here

'Big Ron would refer to himself as "Ginola" - he trained with us and he’d be the star of our training sessions': Ex-Coventry star recalls Atkinson playing like Frenchman in training

'Will Cristiano Ronaldo and Neymar extend their contracts in Saudi Arabia? We play a facilitating job, but it’s down to the players and the clubs to decide' Saudi Pro League chief reveals how talks will work for out-of-contract duo