Milan '88: The inside story of Sacchi's all-conquering kings, as told by them

Matt Barker looks back at the two-time European champions' glorious side, starring a visionary tactician, watertight backline and three superstars from the Netherlands

They held a press conference to announce Marco van Basten’s retirement from football. It was August 17, 1995, a stiflingly hot mid-summer day at Milan’s head offices in the centre of the city. A journalist shuffled in his seat and posed a question to the club’s vice president, Adriano Galliani. “If Baggio is Raffaello,” he asked, “who was Marco van Basten?” Galliani smiled. “Leonardo da Vinci. He was everything. Engineer and artist.”

The Dutch striker’s purity of style and balletic menace in front of goal demanded such superlatives. Crippled by an ankle injury, his last game had been over two years ago, in the Champions League final defeat against Marseille. One fan, 21-year-old Paolo Simonetti, was prepared to offer his own cartilage to the player, even going so far as to meet with the club’s medical staff, only to be told such a proposal was impractical. And now, at the age of just 31, Van Basten’s playing career was over: the first of the fabled trio of olandesi to arrive at the club, and the last to leave.

The Swan of Utrecht, along with compatriots Ruud Gullit and Frank Rijkaard, had won the lot, including back to back European Cups; a feat not repeated since. But it was the manner of these victories that left the club mourning Van Basten’s retirement. Never before had a side harnessed Italian technique and nous with the mercurial talents of the Dutch to such stunning effect.

Under the autocratic eccentricities of manager Arrigo Sacchi, the Rossoneri redefined the modern pressing game, imposing their will on the opposition by squeezing space, playing with a shifting, high-defensive line and putting the emphasis on athletic preparation. It's a tactic that has threaded through the most successful teams of the last quarter of a century, including Sir Alex Ferguson’s Manchester United and, perhaps most famously, Pep Guardiola’s Barcelona.

Beyond the pitch, they were Galacticos before the term was invented. A precursor to the globalised brands of the Champions League era sides; where stars on the team-sheet are important as those above a shirt crest. Trendsetters in every way. And the three Dutchman were at the heart of this revolution: the three names together – ‘Gullit, Van Basten, Rijkaard’ – almost a collective noun for pace, power and panache. Twenty years later, ‘Xavi and Iniesta’ would do the same for tiki-taka Barça.

When Sacchi was asked to compare the two great sides, he was in little doubt. “They were two great teams that played a crucial role in the evolution of the sport. But I coached the best team in history.”

"Sacchi? I don’t know anything about him"

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Sacchi arrived at Parma brimming with ideas, taking his tactical inspiration from two apparent polar opposites: the expressive fluidity of Rinus Michels’ total football at early 1970s Ajax, and the dark arts of catenaccio, as practised by Nereo Rocco’s early 1960s Milan

It all started when Silvio Berlusconi took over an ailing Milan in the summer of 1986, saving the club from likely bankruptcy and, in the process, turning the Italian game on its head.

Under the guidance of Swedish coach Nils Liedholm, the former captain of the great Milan side of the 1950s, the Rossoneri had been struggling to reassert themselves after the trauma of twice being relegated earlier in the decade (one as punishment for their part in the Totonero illegal betting scandal, the other for simply not being good enough). Berlusconi was desperate to introduce a new dynamism, to inject some fresh blood. In 1980, a gradual lifting of the ban on foreign players in Serie A began (it had been introduced in 1964 in the wake of the Azzurri’s poor showing at the European Championship and calamitous 1962 World Cup in Chile). By 1982, clubs were allowed two foreigners; in 1988 the rule became three.

Van Basten and his countryman Ruud Gullit had been targeted as direct replacements for the English duo of Ray Wilkins and Mark Hateley. Gullit had actually been in the city for a medical in January 1987. His club, PSV, were angry at the thought of having their prize asset, under contract for another three years, snatched from them. With Juventus also apparently interested, Milan offered Guillit a three-year deal and three times the wages he was earning in Holland. PSV, with the backing of parent company Phillips’ legal team, played hardball and negotiations dragged on for months. It left a bitter taste with the Dutch club and set a pattern for future transfer sagas, with the practice of paying over the odds for a player becoming known as ‘Berlusconismo’.

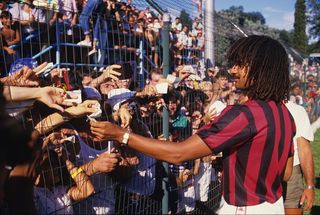

While Milan’s lawyers were staring down their PSV counterparts, a deal had been struck with Ajax for Van Basten. It was a major coup. The player was the current European Golden Boot winner and lauded as heir apparent to his great mentor Johan Cruyff. His arrival at the club was typically unfussy. On April 23, 1987, a large crowd gathered outside the Milan HQ, anxiously scanning nearby streets for an expected motorcade of stretch limos.

Sacchi wasn’t quite the man from nowhere, even if a sceptical press dubbed him Signor Nessuno (Mr Nobody)

The 23-year-old striker suddenly appeared, casually strolling around the corner, flanked by Galliani and Rossoneri director Paolo Taveggia. After cheerfully signing autographs, he chatted with journalists in surprisingly passable Italian. Just as Van Basten was about to walk through the door of the office, one of them asked if he had any thoughts on the rumours of a new coach, said to be arriving that summer to replace the increasingly marginalised Liedholm. “Sacchi?” he shrugged. “I don’t know anything about him. Do you?”

Arrigo Sacchi wasn’t quite the man from nowhere, even if a sceptical press dubbed him Signor Nessuno (Mr Nobody). Sacchi was 40 years old in 1986, the year his Parma side won promotion from the old Serie C1 (Italy’s third tier). He had never played the game professionally. He tried his luck as a left-back with a local amateur team Fusignano, near Ravenna in the Emilia-Romagna region, but switched his attention to coaching after taking a course at Coverciano, the Italian FA’s fabled technical HQ in the suburbs of Florence.

Following brief spells with the youth team at Cesena, the first team at Rimini and that stint with Fiorentina, Sacchi arrived at Parma brimming with ideas, taking his tactical inspiration from two apparent polar opposites: the expressive fluidity of Rinus Michels’ Total Football at early 1970s Ajax, and the dark arts of catenaccio, as practised by Nereo Rocco’s early 1960s Milan.

Rocco's Milan won the European Cup in 1963

Talking exclusively to FourFourTwo, he looks back on those times with a wry smile. “I was a young coach. And, as you know, Mr Nobody can’t have a past, he can only have a future. They asked me how can I be expected to coach footballers if I never played at a professional level. I used to say to them, ‘I didn’t know that if you wanted to be a jockey, you had to have been a horse in a previous life.’”

Bemused Parma players nicknamed him “Pressing”, in honour of his favourite buzzword (they also called him “Valium”, because he could never get to sleep on a Saturday night before a game). Now playing in Serie B, the club was getting noticed for its stingy defence – they let in just seven goals in one season – but equally for its energetic approach, putting pressure on the opposition with a high tempo and using all areas of the pitch.

Berlusconi experienced this first hand when Parma twice beat Milan at San Siro during the 1986/87 Coppa Italia campaign, once during the group stage and then again when they eliminated them in the quarter-finals. The Rossoneri president was intrigued by the opposition coach’s steely focus and drive.

Within days stories appeared in the press that Milan were in talks with Parma about a possible deal. Liedholm was unceremoniously dumped in early April after defeats by Sampdoria (in front of an angry San Siro crowd) and Avellino put a serious dent in the club’s hopes of European qualification. A young, though never quite fresh-faced Fabio Capello, was promoted from the coaching staff to take charge of the remaining games.

Berlusconi had worked hard on Sacchi, boasting to him of Van Basten and Gullit’s arrival. “He was very passionate, he wanted football to be played in the right way,” Sacchi remembers now. “I liked him, I liked his energy, his enthusiasm. His big thing was always that he didn’t just want to win, he wanted to show everyone you could win by playing well, that you could be good at winning.”

The two shared a certain kindred spirit, a desire to overturn the established calcio order, though the media remained unconvinced that this rather strange looking, prematurely aged outsider with his freakish ideas could ever hope to succeed on such a big stage. A spellbinding performance in his first press conference as the new Milan coach brushed aside any doubters. Journalists sat transfixed as Sacchi’s scattergun soundbites spelt out his new coaching philosophy. “The football of the future will be more intellectual than muscular, the mind counts for more than athletic preparation... the opponent that I fear the most? Time.”

"What if Milan don’t qualify for Europe? If, if…"

Van Basten and Gullit, in particular, needed convincing about Sacchi’s methods; they were Dutch, used to creative freedom, not being schooled by a follicly challenged former shoe salesman who had never played the game to any level

In almost perfect contrast with Van Basten’s arrival, Gullit’s Milan entrance was soundtracked by a blaze of police sirens, escorting him through the city streets. Surrounded by frowning carabinieri, flashing cameras, chanting fans and a crowd of onlookers, he revelled in the attention. He also showed his spikey side. Try this for an opening gambit: “They told me in Holland that there are three daily sports papers here and that they’re generally full of rubbish. Is that true?”

Galliani had felt the need to forewarn the assembled hacks that, “Gullit is used to saying what he thinks.” Indeed he was. “What will happen if Milan don’t qualify for Europe? That’s an absurd question, we’ll see what happens at the end of the season. If, if, if… hey, if my mother had a cock she’d be my father.”

Later, the dreadlocked striker would explain that: “I grew up free, I grew up in Amsterdam. Growing up free is great if you’re strong. Maybe I was helped a little by my star sign, Virgo. When I knew what road I was going to take, nobody could stop me. Am I stubborn? Maybe, but also strong and confident.”

Roberto Donadoni still remembers the Dutchman’s incredible strength, his presence and versatility: “He had such physical power that he could have played anywhere. The first time I saw him, it was at a tournament in Barcelona, he was playing as a sweeper! Then he was out on the right wing, in the midfield, second striker and whatever else…”

What will happen if Milan don’t qualify for Europe? That’s an absurd question, we’ll see what happens. If my mother had a cock she’d be my father

Talking now, Sacchi denies there was ever any problem getting his new charges to adapt to his tactics: “There wasn’t resistance as such, it was more a little bit of scepticism. The players weren’t really sure where this was all leading. Paolo Maldini was 19 at the time of Sacchi’s arrival: “It was intense. I used to get home at night feeling exhausted. It was a disaster. Everything was really difficult.”

Van Basten and Gullit, in particular, needed convincing about Sacchi’s methods; they were Dutch, used to creative freedom, not being schooled by a follicly challenged former shoe salesman who had never played the game to any level.

A regular training ground challenge was set up. To prove the importance of the collective, five organised players – the keeper Galli and back four Tassotti, Baresi, Costacurta and Maldini – would be prepared by Sacchi and face off against 10 attackers, Van Basten and Gullit among them. The attacking side had 15 minutes to score, the only rule being if ‘Sacchi’s five’ won the ball, they had to start again from 10 metres inside their own half.

The attackers never scored. Not once. An acceptance of organisation to go with the individual brilliance was born.

Things started well enough, with the two Dutchmen scoring on their Serie A debut, a 3-1 win at Pisa. A home defeat by Roberto Baggio’s Fiorentina raised a few eyebrows, but there was a growing sense that something was happening here and, when everything clicked, Milan were a revelation. Sacchi introduced a new kind of zonal defending (in simple terms marking an area of the pitch, rather than a player), with the zone in question kept fluid as play progressed up the pitch. The defending line would move up, in effect shrinking the area of play. The ball was in constant circulation.

Mauro Tassotti, on the right flank, and Maldini, on the left, were both given the freedom to surge forward, with Carlo Ancelotti expected to cover from the midfield. Franco Baresi would patrol along the back and forage occasionally up the pitch, while fellow central defender Filippo Galli generally held back and put keeper Giovanni Galli’s (no relation) mind at rest. The hard-working midfield needed to be totally in synch with one another, disciplined and focused.

Ancelotti, signed from Roma in the summer, was Sacchi’s representative on the field, a player who would see more of the ball than any other. Alberigo “Bubu” Evani (so nicknamed because of his apparent similarity to Yogi Bear’s sidekick Boo-Boo) would generally stick to the left-hand side, with Angelo Colombo on the right; both would form a tandem with the respective defenders running into more offensive positions behind them.

Just in front of this midfield trio would be Roberto Donadoni, playing as mezza punta, an attacking midfielder (or “half striker”), providing a vital link with the two strikers, with Gullit starting behind Van Basten or, more often than not, Pietro Paolo Virdis, the Sardinian who had previously partnered Hateley up front.

After training, Van Basten would play backgammon with members of the youth team rather than head into the city for a spot of designer shopping or to linger over a caffè macchiato in a swanky bar

Vardis became a crucial player that first season after Van Basten was sidelined with an injury in October 1987. Milan made a fuss of Van Basten, worried that he wasn’t happy. He rarely went out for dinner with his new team-mates, preferring instead to stay in with his wife Lisbeth, “to speak a bit of Dutch” and listen to George Michael records. After training, Van Basten would play backgammon with members of the youth team rather than head into the city for a spot of designer shopping or to linger over a caffè macchiato in a swanky bar. He was always impeccably polite about it all, but clearly not one for socialising. Italians never quite trust people who don’t show their emotions. The press dubbed him “the Iceman”, as much for his seemingly cold personality as for his coolness out on the pitch.

By the time the player was ready to return to first-team action, Milan were bearing down on champions Napoli. The striker made a couple of second-half substitute appearances in April and was pretty much raring to go ahead of a showdown in Naples on May 1. It was to prove a crucial moment in Milan’s history. Arguably, if you want to stretch the point a bit, in post-war Italy’s history too, given the way Berlusconi later used footballing success as a platform on which to enter politics.

Milan arrived in Naples a point behind Diego Maradona’s team. Fresh from winning the derby against Inter the previous weekend, they were in confident mood. Maradona had urged the Napoli fans to turn the Stadio San Paolo into a “graveyard” for the visitors. Vardis put Milan ahead in the 36th minute, only for Maradona to draw level just before half-time with a gorgeous free-kick.

With the volume from the home crowd turned up even further (Napoli needed just a point to ensure they retained the title), Van Basten trotted out as a second-half replacement for Donadoni. Playing off Vardis, he constantly twisted the Napoli defence out of position. His fellow forward edged Milan back in front, before Van Basten provided the killer blow, despite a late Careca goal. Napoli lost their next two games; Milan drew theirs. Sacchi, in his first season at the club, had won the scudetto. For coach and president alike, it was a vindication. Things would never really be the same again.

Rijkaard would occasionally nod off during briefings and tactical discussions

Rijkaard was first used as a defender, something he was happy enough to do, but he was struggling to impose himself within the team, trying to get used to the concept of high zonal lines and pressing

That summer, the two Dutchmen blew the footballing world wide open with their performances for the Oranje during the European Championship, held in the former West Germany, with Van Basten’s startling volleyed goal in the final against the Soviet Union retaining a mythical quality. After the tournament, Cruyff was desperate to bring his protégée to Barcelona, offering Gary Lineker in a swap deal. Milan weren’t interested.

When Van Basten returned to club duty later that summer he had a new swagger. He also had a new sidekick, an old friend from Ajax: Frank Rijkaard. Sacchi had been keen to land the player, but there was a certain risk involved. Rijkaard had just ended a spell at Real Zaragoza, where he was on loan from Portuguese side Sporting, having fallen out with Cruyff in Amsterdam.

His arrival at Milan was completely overshadowed by Inter’s signing of Lothar Matthaus on the same day. Not that Rijkaard was too bothered. He wasn’t much of a talker, but he had a dry sense of humour and his new team-mates quickly warmed to his laconic style off the pitch. On it, they would come to be equally impressed by his ability to push forward as a kind of submerged playmaker, with his corkscrew soul boy curls flapping on his forehead as he ran from a defensive midfield position to feed the ball through to the front players.

Not that we saw too much of that to begin with. Rijkaard was first used as a defender, something he was happy enough to do, but he was struggling to impose himself within the team, trying to get used to the concept of high zonal lines and pressing. He was clearly bemused by Sacchi; there were stories that the Dutchman would occasionally nod off during briefings and tactical discussions and would scoff at the notion that he should be focusing on games that were still weeks away.

It probably came as something of a release for Van Basten, who, as the new 1988/89 season got under way, was becoming increasingly miffed with the way Sacchi would refuse to treat him as an individual, as a player with particular needs. It didn’t help that he still had Cruyff whispering in his ear.

The champions pretty much began the new season where they left off, only coming to a juddering halt in November, when losses against Verona, Atalanta and Napoli (a 4-1 tonking in Naples) set alarm bells ringing. The three Germans at Inter were stealing their Dutch counterparts’ thunder. Van Basten’s grumbles were getting increasingly public (and the player knew he would always have the backing of Berlusconi), while Gullit’s continuing free spirit shtick was starting to grate a little (“I play just like I live my life, or vice versa. When people say I’m an anarchist, I don’t get it. It’s a fault? I see it as a compliment.”)

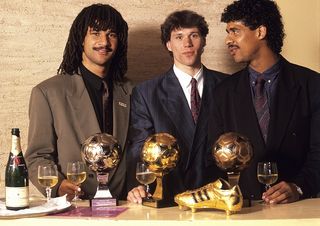

In December 1988, Van Basten won the first of three Ballon d’Or awards as European Footballer of the Year, with Gullit in second place and Rijkaard third. It was the first time club team-mates made up the top three, a trick which would be repeated the following season, with Baresi replacing Gullit. “Marco, the Ballon d’Or? It’s both brilliant and normal at the same time because he’s the best in his position at the moment,” said Johan Cruyff after it was announced. “Mentally, he’s very a strong. A wall! When people compare the two of us, I say he’s my spiritual son.”

It would be 22 years before Messi, Iniesta and Xavi would take all the top three spots for Barça.

"Watching this Milan side, football can never be the same again"

The final, at a packed Camp Nou, against a very useful Steaua Bucharest side, was possibly the greatest embodiment of the Sacchi revolution

By this time, Sacchi’s focus was almost exclusively on the European Cup. That a team could catch the rest of Serie A relatively unaware and win the title wasn’t so unusual during the 1980s: Verona, Roma and, of course, Napoli had all done their bit to break Juve’s domination that decade. Establishing yourself in Europe, where the straight knockout format still held sway, was a completely different matter.

It didn’t all go completely according to plan. A 1-1 second-round home draw against Red Star nearly proved fatal when the then-Yugoslavs took an early lead during the return leg in Belgrade. Milan were on the ropes, only for the match to be abandoned due to fog. The rescheduled game ended in another 1-1 stalemate, before Milan squeezed through on penalties. Victory against Werder Bremen then set up a semi-final with Real Madrid. Van Basten cancelled out Hugo Sánchez’s opener in the first leg, with another 1-1 draw giving few clues as to what was to come in the remarkable return match at San Siro.

Van Basten equalises against Madrid with a stunning header

With press and fans alike still complaining about a 1-1 home draw against a modest Lecce side in Serie A, Sacchi’s Milan set about putting Madrid to the sword. “What we must not do,” Baresi had warned before the game, “is play for a goalless draw.”

Not much danger of that. Ancelotti let fly with a 30-yard shot to open the scoring, Rijkaard headed a second, Gullit got a third from Donadoni’s cross, then Van Basten tucked home a ball headed down by Gullit, and finally Donadoni’s cross-shot found its way through a crowded penalty area. Real Madrid were thumped 5-0. The world took note.

At the end of the game an embarrassed Berlusconi embraced his Madrid counterpart Ramon Mendoza and whispered “I’m sorry.” Real coach Leo Beenhakker, who would leave the club shortly afterwards, looked shell-shocked, telling journalists that Milan had played “exceptional football”. Spanish paper El Mundo Deportivo reported that “It was a Milan recital, with a Dutch accent: Rijkaard, Gullit and Van Basten all scored. Madrid resembled a puppet in the hands of the Italians, who played with them at will, scoring goals whenever they felt like it.”

What we must not do is play for a goalless draw

Jorge Valdano, the former Real Madrid striker and coach, later claimed that “Sacchi’s Milan was a migration of people. This fixation with always being on the attack altered the old parameters of catenaccio which had made Italian football famous throughout the world.” Tassotti acclaimed the win as Milan’s “mission statement… We had proved in Europe that we could dominate any team.”

The final, at a packed Camp Nou, against a very useful Steaua Bucharest side, was possibly the greatest embodiment of the Sacchi revolution. Trapattoni’s Inter had pretty much secured the Italian championship by now, but Milan fans really didn’t care. Decked out in a dazzling white kit, Sacchi’s men again poured forward from the get go. In an age of cagey, measured Euro finals, Milan’s all-attack approach was breathtaking. Milan won 4-0, but it should have been much more; Gullit and Van Basten shared goalscoring duties between them, though both could have got hat-tricks.

“When we went out for the warm-up, we saw the huge numbers of supporters on the terraces,” Baresi recalled. “And we understood that there was no way we could go home without the trophy.” Silviu Lung, the unfortunate Steaua keeper, admitted, “I was exhausted by the end. In all my life, I’d never had so many shots to deal with.”

Italian journalist Gianni Mura claimed in La Repubblica that the win was akin to Italian poet Gabriele d’Annunzio beating Karl Marx. Maldini put it in more simple, if not entirely factually correct, terms: “For all of us, it was our first victory. We all went out on the pitch with enthusiasm, conviction, we felt full of strength.” The following day, French daily sports paper L’Equipe announced that, “Watching this Milan side, football can never be the same again.”

Sacchi achieved what no other coach has since

It was never going to match the majestic punch of the previous year, but Milan were, somehow, back in the final, this time against Sven-Göran Eriksson’s Benfica

The eyes of the world were on Milan, but despite outward appearances of a well-drilled, harmonious squad, bickering was never too far away. Van Basten, fresh from scoring 19 goals in Serie A, was still struggling to connect with Sacchi. When he began to rest Van Basten for certain games, Berlusconi took umbrage. The striker was always Silvio’s favourite, with Rijkaard second in the pecking order. Gullit blew his chances after telling a Dutch newspaper that Berlusconi was “conceited as a man and as a president”.

There were new expectations at the club now, and il Presidente was less than happy about his coach nabbing all the plaudits. Sacchi was being squeezed, having to keep players happy and watch his back. He became steadily more tenacious, determined to see his great “technical project” develop.

It speaks volumes for the strength of the Italian domestic game that this astonishing red-and-black machine would continue to find the going tough in Serie A during the season following their European Cup triumph. Beating Juventus and then Inter in successive weekends was all well and good, but defeats by Cremonese and Ascoli were surely never part of the plan. Maradona was galvanising his Napoli side, pushing them to a second scudetto, despite both Milan and Inter snapping at their heels after a strong second half to the season.

Again, a promising campaign in Europe lifted the mood. Real Madrid were dispatched at the second-round stage by a less earth-shattering 2-1 aggregate score, before Belgian side KV Mechelen were overcome in extra-time with goals from Van Basten and substitute Marco Simone. With a semi-final against Bayern Munich hovering into view, Italian press chatter focused on Milan’s chances of retaining the trophy.

It was never going to match the majestic punch of the previous year, but Milan were, somehow, back in the final, this time against Sven-Göran Eriksson’s Benfica, at Vienna’s Praterstadion. Rijkaard got the winning goal, and a fine one it was too, but the game is probably best remembered now as one of Baresi’s finest in a Milan shirt. Sacchi had achieved what no other coach has done since, winning back-to-back European Cups.

"They were tactically perfect and revolutionary"

Then all of a sudden there was no more catenaccio, but a four-man defence, with a side that attacked, rather than waited to counter-attack. It was a great change

He would stay with Milan for another season, but by early 1991 there was a progressively chilly atmosphere at the club. Sacchi would claim that the hunger was no longer there: “If someone’s hungry and they have something to eat, look what happens. And then look what happens if it’s the first time they’ve eaten anything in years…”

Van Basten was becoming more vocal about being dropped and Gullit was having a rotten time with injuries, amid growing newspaper claims that his time with Milan was up (Rijkaard seemed happy enough though, settling into a more advanced role). Most notably, Berlusconi was becoming increasingly intrusive, at one stage oafishly issuing an ultimatum to his coach to either win him the championship and the European Cup, or say arrivederci. Milan were knocked out of Europe by Marseille in the quarter-finals and finished runners-up in the league for the second year running.

Future Milan striker Jean-Pierre Papin scores against them for Marseille

Capello was duly lined up to replace Sacchi, despite the public protests of both Donadoni and Baresi (though not, tellingly, any of the Dutchmen). The future England manager would open up a new cycle of success for Milan, Van Basten would have one of his best domestic seasons, and Gullit and Rijkaard would continue to flourish in the red and black. Capello was, in many ways, the first coach to adopt Sacchi’s tactical approach, fine tuning it before Van Basten’s injuries cruelly got the better of him and his countrymen left for challenges elsewhere.

Sir Alex Ferguson recently paid tribute to Sacchi’s legacy: “He changed Italian football. He got rid of catenaccio by proposing a high-pressing game, with Maldini pushing forward on the flank. The Italian mentality was to attack with caution. Then all of a sudden there was no more catenaccio, but a four-man defence, with a side that attacked, rather than waited to counter-attack. It was a great change.”

Rafa Benitez is a known advocate of that Milan team (“they had quality, discipline and intensity”), with Jamie Carragher writing in his autobiography about how the Spaniard would ask him to study the early 1990s-vintage Rossoneri: “He handed me DVDs of Arrigo Saachi’s legendary Milan side and was especially eager for me to analyse Franco Baresi’s movements and organisation of the defence.”

For Baresi, he couldn’t quite believe how things had changed in a few short years. “We used to look around and sometimes marvel,” he told FFT in 2009. “With the arrival of Berlusconi, things really changed at the club. When he told us we would go on to be the best club in the world we were all sceptical. But within a couple of years we’d won everything with an amazing style of football.”

Gianluca Vialli, whose Sampdoria would beat Milan to the Serie A title in 1991, agrees. “They were revolutionary because they played so well as a team – tactically they were perfect. The way they pressed high up the pitch rather than dropping deep. It was quite revolutionary and they have been copied ever since.”

Pressing high up the pitch: it all seems so obvious now. Looking back, Sacchi makes a telling point when asked about the Dutch trio and whether we have a tendency to place too much emphasis on them at the expense of the rest of that glorious group of players. “It wasn’t just the Dutch, or the squad, though they were magnificent,” he sighs. “It was the system of play. The system was ultimately the leader out on the pitch; it never got injured or tired. It wasn’t the players who won all those big games. It was the way we played.”

But a system can’t represent a team in the way players can. For this Milan side that honour belongs to the three Tulipani: Gullit, Van Basten and Rijkaard.

This feature first appeared in the October 2013 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe!

Matt Barker is a freelance journalist and regular feature contributor to FourFourTwo magazine. He specialises in Serie A and Italian football, has interviewed players including Michael Owen and Gianluigi Buffon, as well as covering stories such as Silvio Berlusconi's purchase of AC Milan, and Ronaldo's injury-plagued time at Inter Milan at the turn of the century.