Montevideo nasty: Why Nacional vs Penarol is more than a game

The oldest non-UK derby was once contested between two giants of South American football, but as Montevideo's mighty have fallen, violence has increased - on and off the pitch. Sebastian H Garcia reported for the April 2009 FourFourTwo magazine...

Arriving in Montevideo, it feels like you’ve just travelled back in time. Even in 2009, the capital of Uruguay doesn’t overwhelm you with the unbearably frenetic pace of other major cities. It probably never will.

This is a place where human warmth is still winning the battle against ice-cold modernisation. To walk through the city, to look up and see its friendly people coming out onto colonial-style balconies, only reinforces the feeling that you have arrived in another era, not just another place.

Only once you’ve found your feet in the only Uruguayan city with more than one million inhabitants (in a country with roughly three and a half million), does reality kick in and some signs emerge that you are in a 21st century city, after all.

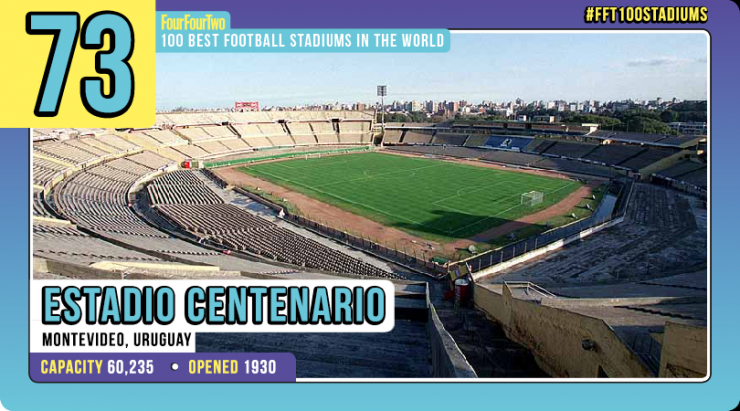

That is until, in the geographical centre of town, you run into the mythical Centenario Stadium.

Completed in 1930 to host the inaugural World Cup finals, the stadium got its name to commemorate the 100-year anniversary of the signing of the Republica Oriental del Uruguay, the country’s first constitution, and was named in 1983 by FIFA as one of football’s top five classic venues (together with the Maracana, Wembley, the San Siro and the Bernabeu).

While the enormous bowl’s concrete seats are edging closer each day to celebrating their own centenary, they never seem to tire of hosting the passion, pleasure, pain and pyrotechnics of the world’s oldest derby match outside the British Isles: Nacional versus Penarol.

The two big teams were described as 'the irreconcilable adversaries of all times, of all years, always in struggle with each other'. This was in 1908

One of the many romantic sports chronicles published in Montevideo’s newspapers back in the beginning of the 20th Century described the two big teams from Uruguay in a colourful and almost obsolete form of Spanish that literally translated as, “the irreconcilable adversaries of all times, of all years, always in struggle with each other”.

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

What is really intriguing about this is that when those words were published, in 1908, Nacional and Penarol had only been playing each other for eight years, and Penarol weren’t even called Penarol.

That journalist’s take on things ended up being more than a report on that particular match, rather an accurate prediction, a premonition almost, of what was to come in the next century and beyond.

The other side of the tracks

On September 28 1891, 118 employees of the British Railways Company (72 Englishmen, 45 Uruguayans and one German) founded a sports club by the name of Central Uruguay Railway Cricket Club (CURCC). Fans soon started referring to it simply as Penarol – the district of Montevideo where the team played – because it was easier than to say the entire name in English.

The name of the district itself comes the very first settler, Giovan Battista Crosa (or Juan Bautista Crosa), an Italian immigrant who arrived in the mid-1700s from the city of Pinerolo, near Turin. Fooled by Crosa’s thick accent, his neighbours referred to the area as, “where the Pinarol man lives”. Soon, it simply became known as Penarol.

Nacional fans claim that their club, founded in 1899, is the older of the two and the whole issue, to this day, is the subject of heated debate between the two sets of fans

To this day, though, there is controversy surrounding the club’s identity. FIFA and the AUF (Uruguayan FA), recognise CURCC as the club that gave birth to Penarol and therefore consider CURCC and Penarol as one and the same club.

Nacional fans, however, have another theory. They claim that CURCC and Club Atletico Penarol co-existed for a while and even played their matches separately and faced each other at some point during 1914, which would make it impossible for them to be considered the same club.

Therefore, Nacional fans claim that their club, founded in 1899, is the older of the two and the whole issue, to this day, is the subject of heated debate between the two sets of fans. What is not in doubt is why Penarol wear black and yellow – they were the colours of the original railways signs.

Nacional, as the name suggests, was founded out of the natives’ need to distinguish themselves from the British immigrants and for practising a sport that had started to captivate Uruguayans. They needed a place to play, somewhere they could call home and the Universidad de la Republica was where students came up with the idea of founding a club that would represent the people of Uruguay.

Nacional was born as a product of a merger between Uruguay Athletic Club (blue shirts) and Montevideo Football Club (red). They were later joined by those from a club called Defensa (white).

While the origin of their colours could be found in a combination of the merging clubs’ shirts, the choice was in fact a decision by the directors, taking the blue, white and red from the flag of Jose Gervasio Artigas, Uruguay’s most important national hero, who was a crucial figure in the fight for independence from the Spanish monarchy.

Continental dominance to national glory

Towards the end of the 19th Century, organised football became an important part of life in Montevideo and the rivalry between Penarol and Nacional emerged to reflect and emphasise the differences between the newly established social classes that co-existed in the city: immigrants and natives.

In a thriving and relatively young city, the arrival of immigrants from Europe started to shape the population and the bonding of the newcomers with the natives was problematic

In a thriving and relatively young city, the arrival of immigrants from Europe started to shape the population and the bonding of the newcomers with the natives was problematic. The locals felt pushed around by the immigrants and more often than not, Europeans would get better jobs as they were better skilled, prompting suspicious and envious glances from the natives.

The newly arrived, most of them from peripheral regions in their home countries (Galicia, Naples, the Basque Country, Piedmont and the Canary Islands, to name a few), felt this hostility and responded by secluding themselves into very tight-knit communities, which eventually led to football clubs’ foundations and the consequent restrictions on membership to the locals.

Locals vs immigrants

Penarol, followed mainly by the foreign communities and the British Railway workers, saw as their biggest rivals Nacional, the team that represented the locals. Most importantly, people saw in football a safe way to express their feelings and in some cases, through their team’s victories, avenge an injustice in their everyday life.

Penarol-Nacional is often compared to Celtic-Rangers in terms of pure noise and passion but lacks the crucial religious aspect of the Old Firm, making it almost impossible to identify each club’s fan-base

At the football ground, people were able to mix with a big crowd and vent their anger or repressed feelings in what was – back then, at least – a relatively safe environment.

As the popularity of the two teams began to grow, the social class differences in the city began to fade and both clubs soon had huge support from fans of every background. And while Penarol-National is often compared to Celtic-Rangers in terms of pure noise and passion, it lacks the crucial religious aspect of the Old Firm, making it almost impossible to identify each club’s fan-base these days.

World Cup victory on home soil in 1930 ushered in Uruguay’s professional era, taking the Nacional-Penarol rivalry up a notch. Two clashes in particular – depending on who you speak to – are part of clasico folklore…

In 1933, Nacional were on the verge of winning the league title when Penarol’s Bahia shot past the Tricolor goalkeeper, Eduardo Garcia. From the rebound, Braulio Castro slotted home into an empty net, sparking furious protests from the Nacional players.

Apparently, the ball hit a wooden bag that belonged to Nacional’s physio that was sitting just off the next to the goalpost, but the referee assumed it had hit the post and allowed the goal to stand. The match – ‘The Derby of the Bag’ – had to be replayed twice before Nacional clinched the title more than a year later.

In 1949, another famous bout failed to go the distance. Penarol took a commanding 2-0 lead in the first half and Nacional’s players didn’t appear after the interval, with rumours that they’d fled via their dressing room window.

The reason? Nacional fans argue that their players scarpered in protest at the referee’s performance, while Penarol fans will tell you that Nacional legged it because they feared a drubbing. That game is known as ‘The Derby of the Leak’.

NEXT: The world's most 'national' derby

The world's most 'national' club derby

This lack of competition from Uruguay’s other cities helped both clubs expand their reach to the entire country

A year later, Uruguay’s squad for the 1950 World Cup comprised nine Penarol players, six from Nacional, and none from outside the capital. This lack of competition from Uruguay’s other cities helped both clubs expand their reach to the entire country, making the clasico a ‘national’ derby than any other game in the world.

To this day, the whole country comes to a standstill when Montevideo’s big two meet. A comprehensive poll conducted in 2006 revealed that they combine to capture the following of 80% (Penarol 45%, Nacional 35%) of football fans in Uruguay. Between them, they’ve also won around 80% of league titles.

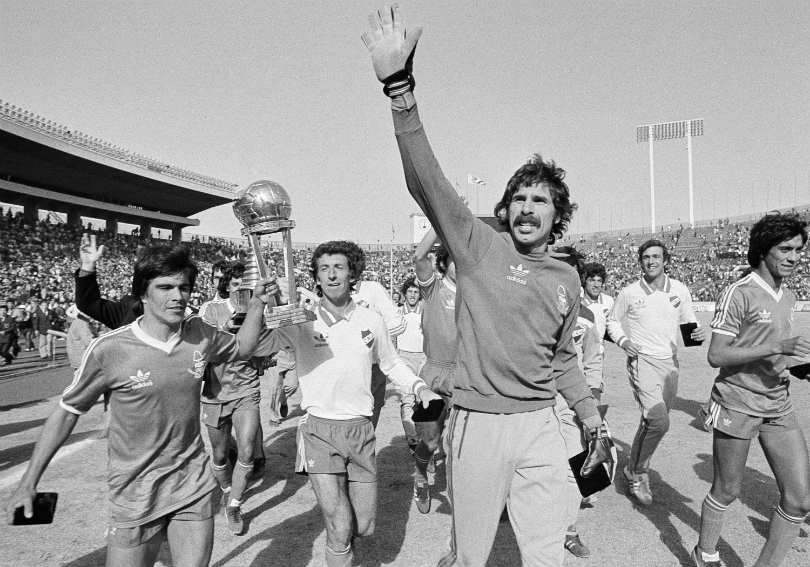

They also boast three ‘world titles’ apiece, Penarol recording famous Intercontinental Cup wins over Eusebio’s Benfica and Gento’s Real Madrid

More significantly, though, both were once giants of South American football. Penarol won the first ever Copa Libertadores in 1960 and went on to win four more (1961, 1966, 1982 and 1987), while Nacional have three successes (1971, 1980 and 1988). Between them, they’ve reached a further seven finals.

They also boast three ‘world titles’ apiece, Penarol recording famous Intercontinental Cup wins over Eusebio’s Benfica and Gento’s Real Madrid, as well as victory over Aston Villa in 1982. Two years earlier, Nacional beat Brian Clough’s Nottingham Forest to preserve their 100% record in the competition.

How the mighty have fallen. Colombia, Paraguay, Chile and now Ecuador have all had Libertadores winners since Nacional become the last Uruguayan side to reach the final 21 years ago. But as success on the continent fades deeper into memory, the domestic rivalry, if anything, matters even more.

“Historically, National-Penarol is one of the world’s most important derbies,” explains Patricio Cambon of Montevideo’s Radio Carue. “In this region, it perhaps only trails Boca-River. People will always care about the clasico, no matter how bad our teams get.”

Indeed, Uruguayan football was already in decline in 1990 when, a week before the game, Nacional’s captain, Enrique Pena, began stoking the fire. “We will surely win this game because our players our men,” he told the media.

“Pena thinks he’s brave,” responded Obdulio Trasante of Penarol. “We’ll see if he can back up his words outside.”

With 10 minutes to go in the match, Pena was sent off and was goaded by Trasante as he headed for an early bath. Seconds later, the entire two squads were going at it. The referee sent off all 11 of Penarol’s players and nine from Nacional (plus two subs), invoking the ‘seven players’ rule to end the match at 0-0.

In 2000, it was Enter The Dragon meets Rocky as the two teams marked the end of a 1-1 draw with a dust-up that resulted in nine players and one coach spending a month in jail.

Fans fear

The clasico is always played at the Centenario, even though it's neither team’s official home, with ticket allocation always split 50-50

It’s mid-summer in Uruguay, with temperatures in Montevideo rising to 40C. Those who didn’t head east to spend a few days at the beach are about to be rewarded with a four-team pre-season ‘friendly cup’ edition of a fixture that is never a friendly.

The clasico is also unique in that it’s always played at the Centenario, even though neither team’s official home, with ticket allocation always split 50-50, creating a cup final atmosphere every time they meet.

Until recently, though, any violence between Nacional and Penarol was largely confined to the pitch, but with a new wave of hooliganism surging through Uruguayan football, the Apertura 2008 tournament – that was supposed to end in mid-December – had its last round of matches postponed until early February, leading to a heightened sense of anticipation as the 2009 Clausura looms.

I was so scared I had to hide inside a supermarket until they were gone. But I’ll keep on coming. I can’t live without my Nacional.

Eighteen-year-old Nacional fan, Elena Varela, is certainly worried. “My worst experience at a clasico was when the Penarol supporters started to vandalise the bus,” she tells FourFourTwo from behind her gigantic sunglasses, Nacional shirt wrapped around her waist.

“I was so scared I had to hide inside a supermarket until they were gone. But I’ll keep on coming. I can’t live without my Nacional.”

“I try to avoid arriving or leaving the stadium through areas in which I could be faced by dangerous Nacional fans,” says Penarol supporter Guillermo Bensano. “I would never hurt or fist-fight with a Nacional fan, but you have to be aware there are people coming to football with different intentions, so it’s better to stay clear of them.”

A fellow Penarol fan in his mid-20s wishes he’d had the benefit of Bensano’s experience. As he makes his way to the Colombes Stand (named after the Parisian district where Uruguay won their first Olympic football gold medal in 1924) he is approached by a bunch of Nacional hooligans outside the entrance to the Amsterdam Stand (named after City where the Sky Blues retained their Olympic title in 1928).

Knowing he’s in trouble and clearly out-numbered, he wisely chooses to keep walking as if he hasn’t noticed the mob. A bare-chested member of the group edges closer, insulting the Penarol fan incessantly, then in one swift movement, he grabs the black and yellow shirt that is hanging from his prey’s shoulders and disappears back into a crowd of fellow Tricolores.

Like something out of a Hollywood film, the police arrive on the scene seconds later, confronting the Nacional throng and ushering Penarol fans in a different direction.

NEXT: The match

A fair result but a sad outcome

A ticket-tape reception for both teams is followed by some of the most vociferous chanting you will ever witness at a football ground.

As FourFourTwo heads for the turnstiles, an announcement comes over the tannoy. “We we allow entrance to supporters carrying small drums, flags, small radios and vacuum flasks.”

Despite the searing heat, people carrying flasks under their arms is one of the first things you will notice when you arrive in Uruguay. People are rarely seen at the football without their flask of mate (pronounced mah-the), a caffeine-laden leaf drink. Much nicer than Bovril.

Inside the stadium, it’s South America at its best. A ticket-tape reception for both teams is followed by some of the most vociferous chanting you will ever witness at a football ground. Penarol’s fans jump up and down as one, erupting into their traditional pre-game war song:

“I leave everything behind, I come to see Penarol

Because the players are going to show me

That they are here to win, that they want to be the champions

That they feel for Penarol the same love I feel.” (It rhymes in Spanish.)

Their team starts brightly and through striker Carlos Bueno, the terrace favourite (and confessed Penarol fan), they take the lead. Minutes later, Argentine left-back Federico Dominguez – making his Nacional debut – receives a red card for an elbow on Bueno, leaving his new team-mates with a mountain to climb.

Climb it they do. Sergio Blanco from the penalty spot just before the break and Adrian Romero in the second half – with Penarol also down to 10 men – give Nacional a much-celebrated victory.

At the full-time whistle, Nacional’s deliriously delighted fans don’t waste the opportunity to remind the enemy of their humble, historically ambiguous roots:

To prove there is no such thing as a friendly between these two teams, Penarol manager Mario Saralegui is forced to resign after the game

"You don’t have any money

You don’t play any cups

You don’t even know when you were born

I bet you want to kill yourself.”

To prove there is no such thing as a friendly between these two teams, Penarol manager Mario Saralegui is forced to resign after the game. Now, you can’t imagine that happening at the Emirates Cup.

Sadly, though, there are those who take the outcome of the match a little too seriously. At around 10.30pm, with both sets fans finally returning home, Hugo Munoz, a 33-year-old Nacional fan, is less than a mile north of the Centenario when he and his friends come face to face with a bunch of Penarol supporters.

One of them takes out a .22 caliber gun and fires it six times at the Tricolors. Munoz takes a bullet to the chest and barely survives, while the aggressor, whose identity is not revealed, is charged with attempted murder.

The latest violent episode in a heated but not so violent rivalry contrasts starkly with Montevideo’s friendly olde worlde ambience, but the city’s law-abiding football fans may be forced to look to the future if they want to return to happier times.

“I don’t see a way for our football teams to be as important and dominant as they were in the past,” says local journalist Patricia Cambon.

But with talk of rebuilding the Centenario as part of a bid to host the centenary World Cup in 2030, at least Penarol and Nacional will have a new stadium to be proud of – and they’ll always have each other.

This feature originally appeared in the April 2009 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe!