A civil war masquerading as football: Why Barcelona vs Real Madrid is more than a game

For legions of fans the Spanish Civil War never really ended: every season it flares up again when Barcelona play Real Madrid. And as each side tries to outdo the other with star players and footballing excellence, the fixture has become the world's most keenly savoured club match. Andy Mitten reported for the September 2003 FourFourTwo magazine

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Five times a week

FourFourTwo Daily

Fantastic football content straight to your inbox! From the latest transfer news, quizzes, videos, features and interviews with the biggest names in the game, plus lots more.

Once a week

...And it’s LIVE!

Sign up to our FREE live football newsletter, tracking all of the biggest games available to watch on the device of your choice. Never miss a kick-off!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

When Real Madrid beat Barcelona to sign David Beckham, Barça fans could only shrug their shoulders. Such is the depressed state of their club that few in Catalunya mustered any outrage.

It hasn’t always been this way. But then there has never been such a gulf in success between Spain’s two biggest clubs and historically ferocious rivals. The Barça-Madrid rivalry has always run far, far deeper than football. The clubs represent two languages, two peoples and, in the view of many Catalans, two countries.

And each of those two countries invests enormous national pride and vast sums in their flagship clubs. Which is why the game they call El Derbi remains, whatever the relative positions of the two sides, probably the most emotionally charged yet glamorous domestic club fixture in the world.

Figo's homecoming

The stadium is hard to fill, and even Barca’s recent average gate of 65,000 means that there are typically 33,000 empty seats

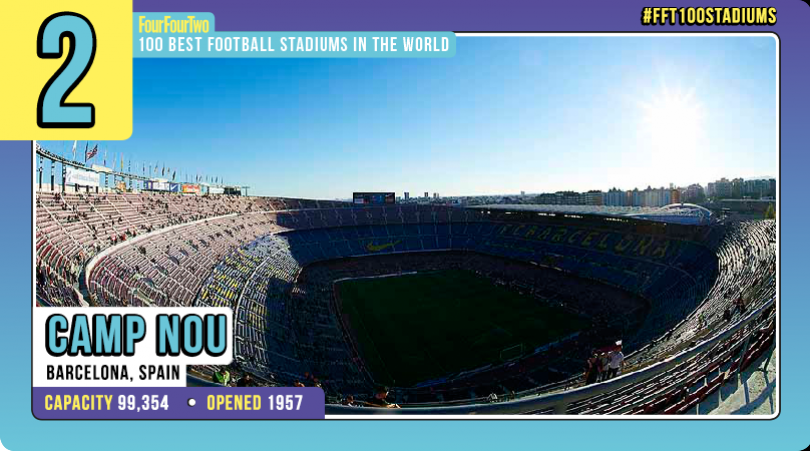

November 23 2002, the Nou Camp, Barcelona: Despite what the TV commentary clichés say, the stadium is no cauldron - for many games the atmosphere is forgettable. Its 98,000 seats spread over three vast tiers may make it European football’s largest citadel, but its size can work against it. The stadium is hard to fill, and even Barca’s recent average gate of 65,000 means that there are typically 33,000 empty seats.

Aside from the ultras who stand behind both goals, Barça’s match-going fans are staunchly middle-class. A typical season ticket costs less than half its equivalent at Old Trafford or Anfield, but watching games on TV with your mates in a bar is more popular.

Locals joke that the stadium's loudest noise comes at half time when Burberry-clad ladies unwrap the tin foil off cured ham sandwiches. Either that or when news comes through that Madrid are losing. Which isn’t often these days.

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

The Nou Camp does match the hype a couple of times a season, though. When the Catalan national side (Jordi Cruyff meets Pep Guardiola) plays one of its non-FIFA recognised matches, the stadium is a feverish amphitheatre of Catalan flags. The other occasion is when Madrid come to town.

Scientists have measured the noise level before kick-off as louder than a 747 at take-off. It hurts. Before Barca’s stirring anthem is played, the teams are read out over the PA. “Makelele, Solari...” then there’s a purposeful pause “...Figo”.

The volume peaks with ear-splitting shrillness - hell hath no fury like a football club whose star player has defected to its most hated rival - and then again when Madrid’s starting 11 run out to the centre circle and applaud the crowd. “The sons of bitches are taking the p**s,” howls a gent nearby, not a year shy of 70.

Spain has four national daily sports (ie. football) papers. Two are Madrid-based, two Barcelona, and one of the latter has choreographed thousands of cards that are held up to display the word ‘Barça’. It’s impressive.

Ronaldo, who scored 43 goals in one season under Bobby Robson at Barca, is absent, officially with a cold, with speculation that he doesn’t want to return and upset Barca fans

The game starts with the pitch enveloped in smoke, the stench of sulphur reaching even up to the third tier from where the players look like ants. Anti-Madrid flags festoon the stadium, one, in English, reading, “Catalonia is not Spain”. Today the rival club presidents sit next to each other, although this isn’t always the case.

As a spectacle, it’s fantastic. Less enthralling are the monkey noises that greet Roberto Carlos’s every touch. Many Catalans not joining in merely snigger. Racism still plagues Spanish football. Every Figo touch is predictably booed, the Portuguese cutting a forlorn figure.

Ronaldo, who scored 43 goals in one season under Bobby Robson at Barça, is absent, officially with a cold, with speculation that he doesn’t want to return and upset Barca fans. Raul later volunteers, “He had a fever, I think”. But the wink that accompanies the quote says it all.

Whisky and a pig's head

With 16 minutes left and the game goalless, Figo attempts to take a corner in front of a sea of contorted young faces the Boixor Nair (crazy boys) ultras. Objects are hurled towards him, and after remonstrating with the referee, he eventually takes an in-swinger, which results in another corner on the opposite side.

As he walks another gauntlet towards the opposite corner, another barrage of beer cans, lighters and plastic bottles rains down, plus an empty glass bottle of J&B whisky (the company were later said to be delighted with the free advertising) and the head of a pig. Yes, that’s right, a pig’s head.

The television screens show several Barca directors laughing, grins which fade as the players are led off the field by the referee to “cool things down”. The Boixos are delighted, while others wonder why the safety nets behind each goal, constructed precisely to prevent objects being thrown on the pitch, are not in place.

The teams re-emerge 10 minutes later and Madrid get another corner which Figo goes to take. Again the missiles start, but this time the Boixos have gone too far for most Barça fans and whistles of derision resound around the stadium. Enough is enough.

The Real Madrid players play their part too. Figo hardly seems in a hurry to take corners and when Guti is substituted he sarcastically applauds the crowd and walks off so slowly that the referee chases him to issue a booking.

The game ends goalless, with Barça the better side and Madrid unable to claim a league victory at the Nou Camp for the first time in 19 years. Players shake hands and Figo shrugs his shoulders to some of his ex-team mates before a wry smile appears. He’s survived.

Figo provoked the situation. He walked over to the corner really slowly, picked up the bottle slowly, went back to the corner and all this consciously and deliberately

“We were not the villains,” declared the (now-ex) Barca president Joan Gaspart after the game. “I don’t like it when people come to our house and provoke us.” “Figo provoked the situation,” added the Barça manager, the surly Louis van Gaal.

“He walked over to the corner really slowly, picked up the bottle slowly, went back to the corner and all this consciously and deliberately, without the referee doing anything to stop it.” Later, the official Barça website quoted two of their Argentinian players, Riquelme and Bonano, saying that the vitriol “wouldn’t have been anything out of the ordinary in Argentina.” So that’s OK, then.

Madrid hit back. Jorge Valdano, Madrid’s cerebral sporting director, retorted that “Figo taking corners is not provocation” whilst Figo himself commented, “I don’t know if Gaspart is taking the piss. As for Van Gaal, I’m surprised. He never said anything about my corners when he was my manager for two years and I saved his arse more than once.” Barcelona were ordered to close their ground for two games, a ban that has still to be commuted.

A passion of hatred

“I will always hate Madrid. There’s just something about them that gets up my nose. I would rather the ground opened up and swallowed me than accept a job with them. In fact, I really do not like speaking about them because it makes me want to vomit.”

Not the words of a febrile Barça ultra, but of Hristo Stoichkov, the tetchy Bulgarian striker whose sublime skills thrilled Catalunya for much of the 1990s. The 1994 European Footballer of The Year tells it how he sees it. And how he is loved for it.

Wearing Barca’s proudly sponsor-free carmine and blue striped shirt, he backed up his words with the type of unflinching commitment every fan demands in games against their biggest rivals.

Against Real Madrid, he scored extravagant last-minute winners and received two red cards, not to mention a two-month suspension for stamping on the referee’s foot. As Stoichkov's fleet heels lost some of their power and he became a more peripheral figure, new coach Louis van Gaal started him just once in his first season. Against Madrid.

Easily Barça’s best player and European Player of the Year in 2000, he moved for a then world record £38m fee after signing a speculative deal with Florentino Perez, a Bernabeu presidential challenger

Stoichkov didn’t disappoint. To this day he remains a hero. Stoichkov has been honoured by two of Barca’s 1,490 penyas (supporters’ clubs) taking his name. Just six of the club’s many foreign players have been granted this honour. Gary Lineker has one, Ladislao Kubala and Stoichkov two. Only Johan Cruyff - the man who revitalised Barca on the field in the ’70s and did even better as manager in the ’90s when his ‘Dream Team’ won four successive championships and the European Cup - has more, with three.

There was another foreigner with two, but Luis Figo was quickly dropped after events in the summer of 2000.

Figo’s move to Real Madrid still has repercussions. Easily Barça’s best player and European Player of the Year in 2000, he moved for a then world record £38m fee after signing a speculative deal with Florentino Perez, a Bernabeu presidential challenger.

Given that Madrid had just won their eighth European Cup under the incumbent club president, few gave Perez a chance, but the influencial construction magnate who lists the Spanish Prime Minister as a friend promised the impossible: vote for me and not only will I clear this club’s preposterous £200m debt, but I’ll also deliver the best player from our rivals. Perez was soon president, each year delivering to Madrid another franchise player - Figo in 2000, Zidane ’01, Ronaldo ’02, Beckham ’03.

In Barcelona there’s a widespread conviction that the Madrid-based authorities, both regional and national, have assisted the club because they see them as a major draw for the city. To clear Real’s £200m debt, Florentino Perez called on his contacts in high places.

He negotiated a deal to sell their prestigiously located training ground, which they'd acquired from the local council for next to nothing 30 years before. Admirable council support or unfair assistance? Barça, of course, have at times enjoyed an equally cosy relationship with the Generalitat, the Catalan autonomous government.

NEXT: Mutual hostility

Whilst Barça have long pleaded persecution, there’s a history of hostility going the other way. In 1916 there were reports of Madrid players being showered with missiles in Barcelona. In 1930, Madrid played a cup final against Athletic Bilbao in Barcelona, the Basques and the Catalans combining to vent their derision of all things white.

Madrid had a perfectly legitimate winner disallowed by a Catalan referee and Bilbao won the game in extra time; the Madrid players were pelted as they returned to the changing rooms. In 1936, just a month before the Spanish Civil War broke out, Real Madrid met Barcelona in the Cup final in Valencia, Real’s Catalan goalkeeper Zamora pulling off one of the greatest saves in Spanish football history in his teams 2-1 victory.

Having lost the first leg 3-0, before the second leg Barcelona’s players were treated to a terrifying changing room visit from Franco’s Director of State Security

In the 1936-39 Spanish Civil War, Barcelona was a Republican stronghold, Madrid the base for Franco’s eventually victorious Falangist rebels. After the war, Atletico Aviacion, the air-force team later to become Atletico Madrid, initially benefited more from Franco’s rule than Real.

Madrid’s official history lists the club’s biggest domestic cup win as an 11-1 victory over Barça in 1943. It describes the result as "majestic" and the players that day as "heroes".

What it doesn't say is that having lost the first leg 3-0, before the second leg Barcelona’s players were treated to a terrifying changing room visit from Franco’s Director of State Security. He ominously reminded them that they were only playing due to the generosity of the regime.

Two teams disguised as two countries

Catalunya is a country and FC Barcelona is their army

Barça’s whole identity has been forged by its persecution by Madrid. Under Franco for 40 years Catalunya was repressed, its language and culture outlawed. In those dark times Barça embodied the spirit and hope of Catalans. It had a club president executed by Francoist troops and the team banned from playing for six months after the fans booed the Spanish national anthem.

Barça's Les Corts stadium and later the Nou Camp became a focal point for Catalan nationalism, a vehicle for a powerful collective identity in defiance of a dictator, one of the few places where the language could be spoken without fear of repression.

Barça and Catalunya have been inseparable ever since. As former coach Bobby Robson put it, “Catalunya is a country and FC Barcelona is their army.” In the light of history and its legacy of pride and resentment, Barça’s motto ‘More than a club’ is no exaggeration.

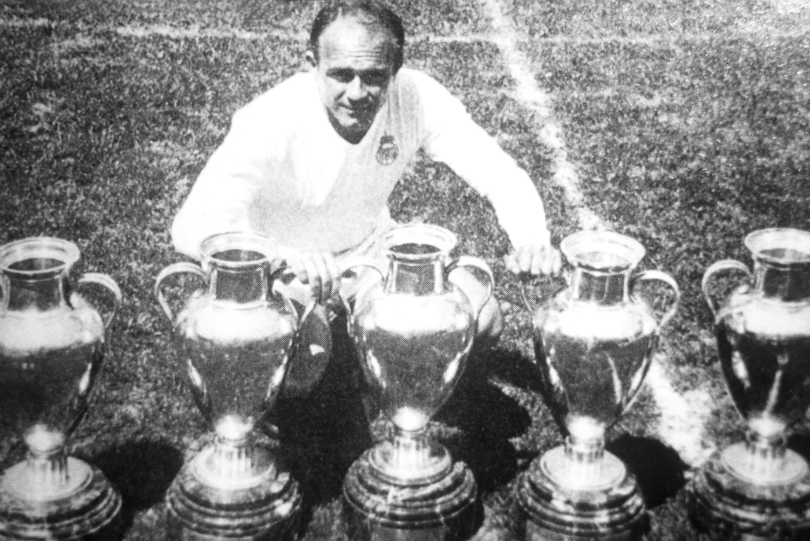

Real Madrid as we know it today only began to take shape when Santiago Bernabeu took up his post as club president in 1944. Bernabeu had fought with Franco’s forces and aligned the club to the new regime, although his first act as president was to send a telegram to Barça saying he hoped for good relations between the two clubs. And yet the story of how Real’s greatest player, Alfredo di Stefano, came to be at the club still causes arguments.

Barcelona agreed a deal to take the Argentinian in 1953 and Madrid entered a counter-offer but was too late. At Madrid’s request, the Spanish Federation intervened and Franco’s General Moscardo passed a law banning the importation of foreign players. Barça were forced to relent until Moscardo brokered a deal for the two clubs to ‘share’ the player.

Barça were outraged, and washed their hands of the whole affair. Madrid got Di Stefano and in his first season won the league for the first time in 21 years, going onto win its first five European Cups. Real Madrid became standard bearers for Spain at a time when it was relatively poor and treated as a pariah state because of its dictator.

Barça had a fine ’50s team too, but government control of the media meant their exploits were overshadowed by Madrid’s - another cause for resentment. Despite its standing as a beacon of Catalan pride, many of Barça’s greatest managers and players have been foreign. Indeed the club was actually founded in 1899 by two expatriate businessmen, a Swiss, Hans Gamper, and an Englishman, Arthur Witty, who wanted to formalise their weekend kickabouts.

In recent decades players like Ladislao Kubala, Diego Maradona, Gary Lineker, Hristo Stoichkov, Rivaldo and Johan Cruyff have joined a list of successful foreign coaches including Helenio Herrera, Rinus Michels, Terry Venables an Louis van Gaal.

Homegrown talent with imports

In Madrid, meanwhile, the idea of a mostly homegrown team lead by outstanding imports (in the ’50s Di Stefano of Argentina and Ferenc Puskas of Hungary) is a formula that has been successfully revived today. Fans hate to admit it, but Barça and Madrid have more in common than they like to think. Both teams benefit from an obsequious media and both are expected to beat all who have the audacity to turn up against them.

Barça have frequently had the more stylish attacking teams, but they won the league just once between 1960 and 1984. Madrid won it 14 times over the same period

The flip side is that when either side loses, the media seldom credit the victors, but would rather magnify the mistakes of the losers. The Madrid press have ran out of superlatives to describe their team so they‘ve settled on one: galacticos - they are so good they must be from another galaxy.

Beckham is el sexto Galatico - the sixth galactic. Madrid’s 2002 centenary year was a cringe-inducing, back-slapping celebration. Barça’s, three years earlier, was not dissimilar. And both are similar in structure too, with fierce rivalries contested in basketball, ice hockey and handball, along with many other sports.

In the ’80s, it was Real’s ‘vulture squad’ who dominated. Emilio Butragueño, Michel, Martin Vasquez, Manolo Sanchis were all products of Real’s youth system, with foreigners Hugo Sanchez and Jorge Valdano brought in to score the goals

However Madrid have prided themselves on a level of consistency that Barcelona have been unable to match. Barça have frequently had the more stylish attacking teams, but they won the league just once between 1960 and 1984. Madrid won it 14 times over the same period.

Just as signing Di Stefano was crucial to Madrid, signing Johan Cruyff was vital to Barcelona (Cruyff’s transfer fee from Ajax was financed by the Banca Catalana - so much for Madrid’s unfair advantage). Madrid had tried to sign Cruyff after he had destroyed them playing for Ajax in April 1973, but he reportedly resented the right-wing connections and was seduced by the idea of living in Barcelona.

In Cruyff’s first game for Barça in the Bernabeu, he scored one and set up three of he other four as his new team won 5-0. Madridistas refer to it as the Black Night and Barça were champions that year. Still, Real Madrid won five of the next six league titles with their ‘Ye-Ye’ team of Santillana, Pirri, Iamacho, Angel and recently axed coach Del Bosque.

Madrid hated Cruyff. He called his son Jordi - ostensibly because he liked the name - but when he went to register the name he was told that it wouldn’t be allowed as it as an outlawed Catalan name. Authority backed down when they realised they couldn’t really afford to upset the most popular man in Catalunya, which only made him a bigger hero.

In the ’80s, it was Madrid’s ‘vulture squad’ who dominated. Emilio Butragueño, Michel, Martin Vasquez, Manolo Sanchis were all products of the club's youth system, with foreigners Hugo Sanchez and Jorge Valdano brought in to score the goals. Despite domestic success, they couldn’t progress beyond the European Cup semi-finals, which they reached three times. And when Cruyff became manager in 1988, Barcelona achieved the kind of consistency that Madrid had become famous for.

Though Madrid’s recent championship success is ‘only’ their fourth since 1990, comparisons between the two clubs today make awkward reading for Catalans.

Madrid, in theory free of debt, have never looked stronger, and Barca, £100m in the red, have reached a nadir so low that the fans are hoping that the combination of new president Joan Laporta and new coach Frank Rijkaard can somehow harness the paid up support of 104,900 members and fulfil their aspiration to make the club better than Real Madrid.

Supporters in the enemies' city

So many Catalunya-based Madrid fans attend that fixtures that Barça fans refer to Espanyol’s Olympic Stadium home as the ‘little Bernabeu’

Take a taxi in Barcelona and the driver is as likely to support Real Madrid as Barça. These are no glory-hunters attracted by the brilliant white of Raul, Zidane, Ronaldo et al, but internal migrants from Castilian Spain who moved to Catalunya in the 1960s to find work. And in Castilian Spain - that is, most of central Spain and excluding the regions - Real Madrid are the most popular team.

FourFourTwo's driver to the game last season was one such fan who was going to meet his Madrid supporting mates to watch the game in the safety of a supporters’ club. The possibility of going into the ground was not one he entertained.

His opportunity to see his team in the flesh comes once a year when they play Barcelona’s second club Espanyol. So many Catalunya-based Madrid fans attend that fixture that Barça fans refer to Espanyol’s Olympic Stadium home as the ‘little Bernabeu’.

While Barça and Madrid fans claim with some justification that it would be unsafe for them to go as away fans to either ground in any serious numbers, their arguments mask an embarrassing truth: their away support is dire. Different reasons are given.

There’s the theory that in buying a ticket for an away ground you are financially enriching a rival club. Then there’s the distance argument. Barcelona to La Coruña, for instance, is 16 hours by road. Yet Newcastle took 7,000 to the San Siro last season, Barca took 700 a month later. The simple fact is that, in Spain, there isn’t a tradition of travelling to away games, unlike in England or Italy for example.

We have so much security but the bus windows get smashed in every time on the way to the ground. Everyone gets out of the window seats

Still, in the '90s, Barca’s Boixos Noit obtained tickets and organised coaches for the Bernabeu. “The police stopped us on the outskirts of Madrid and told us that they were going to protect us,” remembers one who made the journey. “They led us into a trap where we were stoned with bricks and bottles. We travelled back with no windows through the freezing night. It took eight hours.”

It’s the players who experience the sharpest hostility, though. “Once we get to Barcelona it’s just mad, with thousands of fans at the airport and up all night outside our hotel,” Steve McManaman remembers of the annual journey to the Nou Camp. “We have so much security but the bus windows get smashed in every time on the way to the ground. Everyone gets out of the window seats.

"We pull the curtains closed and edge into the middle with some in the aisle but there’s not room for all of us there. People stand up and you just know what’s going to happen. I’ve never been hit and thankfully the windows are reinforced. They’ve got two layers so if the outside smashes it doesn’t come through.”

Even though they are friends off the field McManaman chooses not to sit with Figo for that one. Figo first returned in October 2000 to a welter of abuse. Every time he strayed close to the edge of the pitch - which he’s inclined to do - a rubbish truck seemed to empty its contents in his direction from above, including, among the bottles and oranges, five mobiles, unused credit and all. “It was impossible to concentrate,” sighs McManaman. Barça won 2-0.

Figo wasn’t the complete traitor that the Catalan media portrayed. Barça officials were sending him mixed signals about a new contract, and he called their bluff. He claims that the media and certain Barcelona officials conspired against him and that he still has happy memories from his time in Catalunya. Figo returned to the Nou Camp for a second time in November 2002. Most expected intensity to have eased. It hadn’t.

NEXT: The world's biggest game

The world's biggest game

The Asturian midfielder, the lungs of the current Barça team, stands guilty of swapping white for red and blue six years ago

April 19 2003, the Bernabeu stadium, Madrid: it sounds like a bomb has just gone off. Given that the Basque separatist group ETA had marked the previous game between Real Madrid and Barcelona with two car bombs close to the Bernabeu, everyone is worried. As laughter permeates the smoky haze and silhouettes become faces, it’s clear the explosion is nothing more than a firecracker - someone’s idea of a laugh.

In a street of nondescript mid-rise apartments behind the stadium’s south end, the road has been blocked off by the police and the area is now the domain of Madrid's right-wing Ultra Sur. Lads in Londsdale and Harrington jackets, snide tight jeans and Doc Marten’s boots stand around drinking and singing, “Luis Enrique hijo de puta” (son of a bitch).

The Asturian midfielder, the lungs of the current Barça team, stands guilty of swapping white for carmine and blue six years ago, his yellow-and-red striped captain’s armband being the senyera, the Catalan flag, in miniature.

Unlike in England where Manchester United and Liverpool haven't traded directly for 40 years, many famous players have swapped, including Michael Laudrup, Bernd Schuster and the political football Alfredo di Stefano. All were portrayed as turncoats and suffered for it.

Some ultras wear paramilitary regalia and caps that wouldn't look out of place on a traffic warden. They sing Viva España and one ultra swings the blue and white scarf of Espanyol, Barcelona’s local and historically pro-Spanish rivals. There’s a black van with their neo-fascist logo on the side, brought to transport their paraphernalia of flags, banners - and flash bombs.

Individually, they don’t look much but en masse they’re intimidating. Attempts to make eye contact are met with a hostile glare. “It’s not normally like this,” says Madrid fan Ivan Femandez. “It’s because Barcelona are here.”

We supported and contributed to Barcelona’s Olympics and we were proud that they took place in Spain, but they are against Madrid’s bid for 2012. Why?

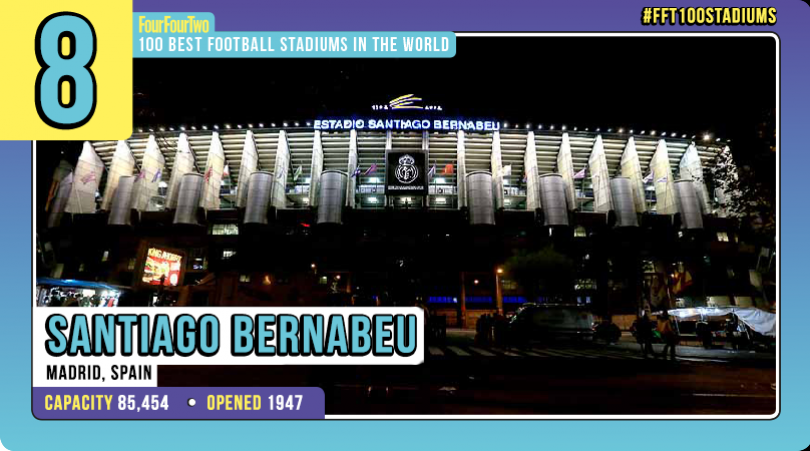

His father, Juan Antonio, is socio (member) number 1447, and has been since 1947, the year a lawyer named Santiago Bernabeu raised money through public subscriptions to build a new stadium. He’s 75 and talks warmly about the greats he’s seen grace his team from Di Stefano to the current stellar hero, the most popular man in Spain, Raul.

However, the mood darkens when he talks about the visitors from Catalunya. “They don’t see themselves as Spanish and reject anything that comes from Madrid because it’s the capital.

"I know Barcelona is very pretty and that most of the people are fine, but others have an inferiority complex with Madrid. We supported and contributed to Barcelona’s Olympics and we were proud that they took place in Spain, but they are against Madrid’s bid for 2012. Why?”

Another firecracker goes off. It's not as close as the first one, but the atmosphere is tense and the police move everyone on.

To the Bernabeu

The Bernabeu is situated on the Paseo de la Castellana (formerly called Avenida del Generalisimo Franco), a wide, leafy thoroughfare lined with skyscrapers in the heart of commercial Madrid. Jester hat-wearing fans queue patiently against the backdrop of a cheesy commercial radio road shows to access the club shop, where you can have your head superimposed next to Steve McManaman’s before paying at one of the three tills.

Surprisingly for a club the size of Real, it feels somewhat small-scale. It’s no wonder both Barça and Real cite Manchester United as their commercial role model. Having long realised the value of the day-tripping or corporate visitor, Old Trafford’s Megastore has 20 tills.

“Barcelona do not matter any more,” says Pablo, a Madrid socio for 40 of his 41 years. “They are like the shit from a dog that sticks in your shoes when you walk in it by mistake. Sometimes we have to shake it off. How can we take them seriously when they give us their best player? Catalans are peseteros (moneygrabbers). They claim to be closer to Europe, but they are so serious we don’t know if they are joking or not.”

Having divided his time between Barcelona and Madrid for over a decade, Lancastrian Michael Turner has a more balanced view of the rivals. “Even people who know nothing about football will watch the Barça vs Madrid game. If it was between two countries it would be called racism, but because it’s between two regions it’s called rivalry.

"Catalans believe that Madrileños are superficial and too big for their boots. They believe that Barça players are playing for an ethical cause, unlike those who play for Madrid. They consider themselves better educated and superior beings. Catalans think they embody the upright nature that people like Lineker or Bobby Robson demonstrated - that’s partly why they were so highly thought of.

“Barceloneses are proud of their city, whereas Madrileños tend to complain more about the local administration, the traffic. There’s actually a lot of respect in Madrid for the way things are done in Barcelona, the way they organised the ’92 Olympic games for example.

"The dislike is definitely more from the Catalans and that’s because of the political history of repression. That said, the majority of Catalans are reasonably happy with their lot. They would like respect within a federal framework and a little more, but not complete, autonomy from Spain.”

And football?

“There’s serious envy at Madrid’s current ascendancy. The difference is that Madrid have had a director of football (Jorge Valdano) who knows who to buy. Barcelona haven’t. Despite lavishing money, they’ve bought a succession of players who haven’t succeeded.”

Despite having 23,000 fewer seats, the Bernabeu appears more imposing as it towers into the Iberian sky

Several of those under-performing Barça players stride purposely into the centre circle of the Bernabeu, a tighter, steeper, vortex of seats than the Nou Camp. Despite having 23,000 fewer seats, the Bernabeu appears more imposing as it towers into the Iberian sky.

It’s from the inside that both stadiums impress, their outer exposed tiers of concrete contributing little of aesthetic note. The Barca players communicate their appreciation of the crowd, knowing that it will be met by whistles which, although strident, don’t compare with the Figo abuse.

As in the Nou Camp, the majority of supporters are middle-aged and middle-class, save for the vocal Ultras behind the goal, their anti-Catalan insults - “Separatist bastards”, “Polish shits” (they class Catalans as a mongrel race) are drowned out by the club anthem Hala Madrid which is more opera house than stadium rock.

Officially, the Ultra Sur are self-financing, but rumours persist that they receive tickets and travel assistance from club officials. The same is said of the Boixos in Barcelona. With both Clubs’ presidents democratically elected, it seems hardly likely that candidates would freeze out their most fanatical followers if they are to count on their votes in the next election.

There’s a 27-point gap between the two sides, the biggest for 74 years, and the 325 travelling Barça fans, tucked away in the nosebleed seats can’t be optimistic. But Barça, despite their wretched league form, seem inspired, and it’s Luis Enrique who grabs a deserved equaliser. He runs to the corner before pointing to his name as objects begin to fall around him from the stands above.

Even in April, Madrid is cold enough for the stadium’s heaters, under the lip of the third tier, to kick into action. The aficionados are not warmed by the performance on the pitch though, and Real stars or not - are booed off the field. Never mind the huge gap separating champions Real and sixth-placed Barcelona, never mind the signing of Beckham from under Barcelona’s noses - not beating their deadliest rivals on the pitch either home or away this season really annoys the Madrid faithful. And the feeling is, and always will be, mutual.

This feature originally appeared in the September 2003 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe!

Andy Mitten has interviewed the likes of Lionel Messi, Eric Cantona, Sir Alex Ferguson and Diego Maradona for FourFourTwo magazine. He also founded and is editor of United We Stand, the Manchester United fanzine, and contributes to a number of publications, including GQ, the BBC and The Athletic.

Join The Club

Join The Club