Crystal Palace vs Apartheid: The tale of the Eagles' summer of 1992

30 years ago, Crystal Palace headed to South Africa – a country on the brink of civil war following the end of Apartheid – for a pioneering pre-season tour. As Ed Aarons explains, it was far from plain sailing...

This feature on Crystal Palace was originally published in the August 2012 edition of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe here

John Salako knew things were different in South Africa, but it wasn’t until the final night of Crystal Palace’s 1992 pre-season tour that he saw just how different. A few hours after Steve Coppell’s Eagles lost 2-1 to Orlando Pirates in Durban, Salako and the rest of the players were sampling the Indian Ocean city’s nocturnal delights.

“We were at a club having a few drinks and doing a real bit of bonding at the end of a great trip,” he recalls. “Most of us were about to go back to the hotel but [Mark] Brighty and Eric [Young] wanted to go somewhere else. It was pretty late by then, but the guy who had been sorting everything out for us agreed to take them. When they got there, they ran into some Afrikaners. They were big guys who were looking for a bit of trouble and didn’t want them in there.”

Sensing danger, Bright and strapping former Wimbledon centre-back Young – nicknamed ‘Ninja’ for his trademark headband – made a quick decision. Time to leave. “They both came back pretty shaken up,” Salako recalls. “It was the first time on the trip we had seen anything like that but it was a real reminder that things were still very edgy over there.”

In July 1992, South Africa hovered on the brink of civil war. After the celebrations that had greeted Nelson Mandela’s release from prison two years earlier, 46 people were massacred by Inkatha Freedom Party militia in Boipatong on June 17.

Future Bafana Bafana captain Aaron Mokoena, then an 11-year-old resident of the township located 50 miles to the south-west of Johannesburg, later recounted that his mother had dressed him up as a girl to keep him safe from the machete-wielding mob. In response, African National Congress (ANC) leader Mandela suspended negotiations with President FW de Klerk, accusing the government of setting the country on a “collision course” by failing to stop the violence and finally bring down the curtain on the hated apartheid regime.

It was against this backdrop of political uncertainty that Salako, Bright, Young and the rest of Crystal Palace’s multi-racial squad landed at Johannesburg’s Jan Smuts Airport three weeks later. Traditionally, the south Londoners had spent pre-season playing lower-league opponents at picturesque grounds in rural Sweden. But with the inaugural Premier League season about to kick off, chairman Ron Noades had accepted an invitation to become the first British club to visit South Africa since Tottenham in 1963.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

“It felt special to us that we were flying the flag,” he told FFT, years later. “We knew there may be a situation where we would take our players to places where some were allowed and some weren’t. It was a test, really, because there was no way we could have stood for any of that. If one player went, the lot went.”

Since the establishment of the first non-racial league in the mid-70s, football had taken a lead in fighting against the injustices of apartheid in South Africa. In direct contravention of the laws of the land, leading clubs Orlando Pirates and Kaizer Chiefs were regularly fielding ‘mixed’ sides before the 1990s, as white players were often smuggled into Soweto to play home matches.

Crystal Palace in South Africa: A seismic change in South African football

“The government knew they couldn’t stop everyone playing together,” says journalist Billy Cooper, who has covered the South African game for nearly 40 years. “All it needed was to be rubber-stamped in 1994, but football had long been different to the rest of the country.”

Yet the ending of the international sports boycott following Mandela’s release from prison still brought about a seismic change in South African football. Their readmittance to FIFA in November 1991 coincided with the emergence of satellite TV, while clubs were flooded by new sponsorship deals with big companies who were keen to establish links with 40 million potential customers who had previously been of no interest to them.

“All the money in South Africa was white at that stage and they realised they had to get involved in the black market, which meant football,” recalls Peter Auf der Heyde, who set up the South African Soccer Yearbook in 1992. “That opened up a lot of doors for people to get seriously rich out of the sport.”

In a country where support for the English game has always been fanatical given the number of expatriates, fledgling TV company M-Net also sensed an opportunity. CEO Barry Lambert had already secured the rights to screen the first Premier League season the following year on their new dedicated sports channel, and with the sporting boycott lifted, he and Chris Day from African Sports Promotions sounded out heavyweights Liverpool, Manchester United and Arsenal about a pre-season tour.

Politely rebuffed, they turned to Palace, who had come so close to winning the FA Cup final against United in 1990 and finished third in the First Division a year later under Coppell. “We were approached about six months beforehand to see if we might be interested,” remembers Noades. “At that time, pre-season tours were all about generating some income for the club. Other teams like Manchester United could demand lots of money but no one wanted to go to South Africa because of all the problems there still were. It was unknown territory.”

For an ambitious club like Palace, though, the £100,000 fee and all-expenses-paid trip on offer to play two friendlies against Chiefs and Pirates in Johannesburg and Durban respectively was too good to turn down. Petrol company SASOL had stumped up most of the cash for the trip, on the understanding that Coppell would bring all of his first-team stars, including England goalkeeper Nigel Martyn, captain Geoff Thomas, Chris Coleman and a young Gareth Southgate.

Palace ended the last ever First Division season in a disappointing 10th position after selling Ian Wright to Arsenal in September for a club-record £2.5 million and losing Salako to a knee injury in their very next match. By the time Coppell’s squad returned from their summer break to prepare for their African adventure, however, there were genuine concerns about whether the tour could take place after events in Boipatong left the country on a knife-edge.

Supporting Mandela

“We made a few phone calls to the Foreign Office just to get confirmation that it was OK for us to travel,” admits Noades. “I think some of the black players were also a bit unsure given the background of the time, but they had a choice of not going if they didn’t want to and nobody dropped out. I felt we were supporting all the progress they had made in South Africa over the past few years.”

Salako adds: “We did have a meeting but I think we were all together. We thought it was a positive thing because it showed we were supporting Mandela and everything they were trying to do to take the country forward.”

A week before Palace left London, Bafana Bafana – a Zulu nickname meaning ‘The Boys’ that was later coined by journalists from The Sowetan newspaper – had made their long-awaited debut in international football.

Chiefs midfielder ‘Doctor’ Khumalo scored the winner from the penalty spot against Cameroon in Durban, before two more games against the same opposition ended in a draw and a defeat. “This was all new to us,” remembers Cooper. “Everyone was so excited for the matches against Cameroon because we had been waiting for so long. A few days later, Palace arrived and there was a real fuss because everyone had seen them in the FA Cup final and it was the first time in so long we’d seen foreign players in the flesh.”

Palace’s 23-man squad had several high-profile black stars that made them one of England’s most pioneering teams of the era. However, some comments allegedly made by Noades a few months earlier about their “lack of work ethic” in an interview with Garth Crooks for a Channel 4 documentary called Football United had put the spotlight on the chairman back home. Over in race-obsessed South Africa, this was big news.

“In the first press conference we had at the airport, all the journalists were asking me about it,” says Noades. “But as far as I’m concerned it had all been taken out of context. We were a great example of how a mixture of races could make up a successful team.”

The players were taken to a five-star Johannesburg hotel for their first night but failed to get much sleep after a machine gun fight erupted between two rival taxi firms on the streets outside. After spending the next day out on safari and sampling South Africa’s famous braai [barbeque] culture, the squad went to Winnie Mandela’s house in Soweto and met the future president’s wife.

They held a coaching session for a group of local schoolchildren in the country’s biggest township – then home to around three million people. With security tight, Noades remembers being driven through the streets to a tiny non-league stadium, and no one was allowed off their coach until the main gates had been padlocked behind them.

The other side of South Africa

“It was one of the best experiences of my life,” says Salako. “But seeing how people lived in the townships was horrific. It brought home how it was over there. You’re pretty much sheltered from it all as a player: we were largely kept within the hotels where most people staying were white. The contrast between the poor and the wealthy was incredible. It was difficult to come to terms with, although it was a situation we were hoping to help change.”

Auf der Heyde adds: “They were confronted with the other side of South Africa. For the players who had probably never seen anything like that before, it left a real impression.”

Scheduled for July 18, 1992 – Mandela’s 74th birthday – Palace’s first match against Kaizer Chiefs was held at the FNB Stadium (now Soccer City) on the outskirts of Soweto. ‘Madiba’ himself had planned to be there until pressing matters at the United Nations in New York meant he was forced to miss his favourite team make history in front of 55,000 fans.

Praised by Chiefs founder Kaizer Motaung in his programme notes for the “courage and foresight” they had shown by coming to South Africa, Palace lined up as promised with their strongest available side, with Salako making his comeback on the bench after 10 months out. For the Chiefs, future Leeds legend Lucas Radebe was in central defence, while Khumalo – fresh from his historic goal against Cameroon – provided the wizardry in midfield.

“We felt really confident going into the game because we were reigning South African champions,” says Khumalo. “But Palace were also a good team and we found them very physical compared to what we were used to. We were also lacking a bit of experience as this was the first time we had played a team from Europe. They had come from a league that was already well established, which made it difficult for us.”

Bright’s opener in the 10th minute gave Coppell’s side the lead, but the Chiefs equalised seven minutes later through burly striker Shane MacGregor. A moment of inspiration from Khumalo then sent the stadium into a frenzy when his cross set up Ace Khuse, and the score stayed the same until midway through the second half. Bright equalised and it was left to Salako to mark his return in style with the winner 12 minutes from time. “It was a very emotional day for me because I had only just come back from being out for so long,” remembers the five-cap England winger. “It was an incredible game and we were really happy to win it at the end.”

Afterwards, Noades presented his players with a present to commemorate the trip. “I went into Jo’burg before the game and bought them all a Krugerrand [gold coin] as a memento,” he recalls. “But I think mine ended up being stolen from my house in England.”

Noades and the Zulu dancers

Twenty-four hours later, a weakened Palace team lined up at King’s Park in Durban for their match against Pirates. Six visiting supporters who had made the trip independently were among a crowd of around 45,000 who packed into a stadium previously reserved for rugby by the apartheid regime.

Traditional Zulu Warrior dancers provided the pre-match entertainment and Noades almost unwittingly found himself part of their display. “I was on the pitch taking pictures and they were all moving towards me slowly,” he remembers. “When I looked up, suddenly they were only about six feet away from me so I was pretty scared! It was fantastic.”

A tight game saw the sides go in level at the break, before a goal from Brazilian striker Pio Noguiera in the 59th minute gave the hosts the advantage. Pandemonium ensued three minutes later when he added a second from what looked like a suspiciously offside position, with the referee forced to stop the game after missiles were thrown onto the pitch.

“It was a fairly volatile atmosphere: most of the players didn’t realise how intimidating it might be,” recalls Salako. “There was a great moat around the pitch – it was incredible to play in a stadium like that. For fear there may be problems, they got us all to stand on the other side of the pitch until everything calmed down.”

“That happened all the time,” adds Cooper (as recently as 2011, Pirates supporters were fined for throwing cabbages at match officials in a cup final in Durban). “If the fans were worried the officials might change their minds, they would try to intimidate them by throwing missiles so it obviously worked!”

A tired Palace eventually pulled one back through Bright nine minutes from time but the Pirates hung on to claim the victory and, most importantly, bragging rights over their fierce rivals, the Chiefs. Out on the town afterwards, Salako and the rest of the players found their two television appearances had made them the centre of attention for all the right reasons.

“Everyone seemed to know who we were – you don’t expect that so far from home,” he recalls. “We were mobbed and everyone wanted our autographs. I suppose what happened afterwards with Mark and Eric could have happened anywhere really – someone pulled a Stanley knife on us during another pre-season tour to Ireland.”

It was almost another two years before Mandela finally became South Africa’s first democratically elected President. The Bisho massacre in September 1992 – when 29 ANC supporters were shot dead by government forces – again briefly threatened to ignite a civil war before peace negotiations finally resumed with De Klerk.

Meanwhile, Palace embarked on what turned into a nightmare season, when they were relegated on the final day with a top-flight record of 49 points. Some fans pointed the finger at Noades for organising a far-flung pre-season tour, but the chairman has no regrets. “We got a lot of TV coverage there, which was really good for the club because it was all still new to us. We were a Cinderella story, I suppose, and I was very proud of what we had done,” he says. “But even in South Africa I had a fear of being relegated.”

By January 1996, Bafana Bafana had been crowned African champions to follow up the Pirates’ triumph in the CAF Champions League six months earlier, as the country’s footballers helped to celebrate the birth of a new nation in style. Most of England’s top clubs touched down at Johannesburg’s renamed OR Tambo International Airport over the next decade, culminating with the establishment of the Vodacom Challenge in 2006, which pits the Chiefs and the Pirates against a touring Premier League side on an annual basis.

But for Salako, being the first remains a source of great pride. “It was an incredible time for Palace because we were all young and impressionable and things had been going so well. Going to South Africa was one of the really memorable moments for us all. The country was on the verge of achieving something great and to be a part of that was very special.”

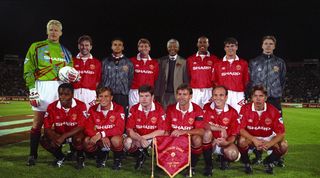

For a limited time, you can get five copies of FourFourTwo for just £5! The offer ends on May 2, 2022. First, fourth and sixth images courtesy of grandstandimages.co.za