Thirty years on, how El Tel tamed the Orwellian beast of Barcelona and won La Liga

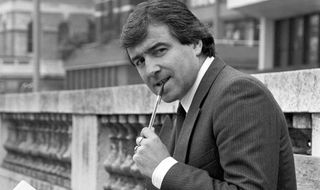

As the Catalans begin a new era under Luis Enrique, Luke Ginnell looks back 30 years when Terry Venables pitched up at the Nou Camp as an unlikely hero...

Picture the city of Barcelona in the summer of 1984. The place is getting a facelift, with cranes dotting the skyline and new parks and plazas springing up across the city. The streets and boulevards buzz with an optimism brought on by a regeneration that began late in the previous decade.

It’s a sun-drenched scene, tourists gawping enviously as locals amble down tight alleys and broad avenues, lounge in cafés shaded by parasols and generally exalt in the underlying feeling of renaissance. There’s a colourful, glamorous vibe about this city; Barcelona is on the up.

Now insert Terry Venables into that scene.

For 1984 was the year that the man later styled by journalist Mihir Bose as the “False Messiah” walked into the Nou Camp as coach of FC Barcelona for the first time, a club as much in need of revival as the city itself. Venables was an unlikely saviour; the previous 24 years of his professional life had revolved around a quadrangle of locations all within a 30-mile radius of his birthplace in Dagenham. Yet here he was managing one of the world’s biggest and most iconic clubs, a cockney in charge of Catalonia's most powerful symbol.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Venables took over during a period of turbulence at Barça. Diego Maradona was on his way out, his constant feuding with club president Josep Lluís Núñez having made the act of football a mere sideshow to the El Diego soap opera. Núñez himself ran the club as if it were the Airstrip One of George Orwell’s 1984, a grand institution moulded into a personal fiefdom through inane propaganda, ruthless politicking and outright intimidation.

“We know that no one ever seizes power with the intention of relinquishing it,” wrote Orwell, words that were oddly reflective of Núñez’s reign as Barça president, during which time he had ruthlessly seen off all would-be challengers to his domination of the club. If Barça was Airstrip One then Núñez was Big Brother and, fittingly, 1984 was to prove one of the most pivotal years of his regime.

The nobody

Núñez was desperate for success. The club was both his ticket to a high society that had shunned him and a very expensive advertisement for his commercial interests. But it was also a major vanity project, an ego boost that became an obsession. He’d gobbled up the second-hand glory brought by victories in the cup and in minor European competitions, but the trophy Núñez craved so much – the Spanish league – had eluded him since he took over Barça in 1978.

Part of the reason for the decline in league form was the self-inflicted damage caused by the president and his cronies. The team itself had become stagnant against this background of on-field scandal, administrative chicanery and dictatorial government. If Barça were going anywhere, it was at best sideways, but they were making a hell of a fuss while doing so. Through some slightly unlikely combination of circumstance, Terry Venables was the man entrusted to find the solution to this problem.

“Venables was a nobody when he came to Barcelona,” Catalan journalist Pilar Calvo told Simon Kuper in 1994. The manager he replaced, César Luis Menotti, had led Argentina to a World Cup victory in 1978 and was an iconic figure in world football, so it was unsurprising that Barça fans were underwhelmed by the new man in charge. They wanted something more than an unknown Englishman who’d never won a single top-flight league title as either player or manager.

However, Núñez thought differently, as pointed out by writer Jimmy Burns: “Terry Venables and Josep Lluís Núñez were the right men meeting at the right place at the right time in that summer of 1984. Each man’s ambition complemented the other’s. So far, while Núñez’s successes had yet to earn him respect, Venables’ reputation had always exceeded his achievements.”

It was a reputation brought to the attention of Núñez by Bobby Robson, another Englishman who had previously been approached for the same job. Núñez wanted a motivated, up-and-coming English manager for the team – there was a feeling that World Cup-winning Menotti may not have been sufficiently driven to give his all for Barça – and Robson’s recommendation of Venables was hugely significant in the latter’s appointment.

The English are coming

Venables was not, in fact, the first Englishman to manage Barça – nor was he the last; Robson eventually took charge in 1996. Ever since the club’s foundation, the English had played their part in its management and, prior to Venables, the most recent incarnation of that tradition was Vic Buckingham. According to The Rough Guide to Cult Football, the former Fulham manager was best remembered at Barça for “wearing tweed jackets and silk ties, drinking cocktails, playing golf and gossiping about horse racing. To his players and to officials, it seemed as if the club had somehow hired Professor Henry Higgins from My Fair Lady.”

Though Buckingham’s almost caricatured style was wholly different to that of Venables, there was a parallel between the two men beyond their nationality. Like Venables, Buckingham had taken over at a tough time for Barça, but regenerated the side to the extent that they won the Copa del Rey in 1971. Ultimately, he handed over the club to Rinus Michels in a much better state than he found it, and most onlookers in '84 felt that similarly modest achievements were likely to be the best they could expect from Venables.

One of most pressing issues when Venables took over was deciding what to do with Maradona. “I truly believed Barcelona was the club for me, the best club in the world,” said Maradona in his autobiography. “But I didn’t imagine [that] I was going to come across an imbecile like the president.”

The player had been in conflict with Núñez for what seemed like an eternity, a battle rooted in ideology as the ongoing spat between Menotti’s Barça and the Athletic Bilbao of Javier Clemente. Menotti preached a creative, artistic brand of football, while the abrasive Clemente favoured a rather more rudimental approach to the game, and the two men’s teams had clashed violently on a number of occasions.

The situation was worsened by the on-pitch encroachment of political tension between Catalonia and the Basque country, and the rivalry reached its peak in the Copa del Rey final of 1984, when a mass brawl erupted. The central figure in this conflict, of course, was Maradona, and his kung fu kicking during the melee was very much the last straw in relation to his career at Barça.

The animosity between playmaker and president escalated to the point that Núñez ordered Maradona’s passport to be seized. Diego responded by arriving in person at Núñez’s office and threatening to smash everything in the room. Maradona was the epitome of Menottismo on the pitch, but it was his adherence to a similarly carefree approach off it that alienated him from the more conservative Núñez – as well as Menotti’s predecessor as manager, the authoritarian Udo Lattek.

It was clear that Maradona would not survive at Barça, where he’d become too dangerous a symbol of free thinking for the administration to stomach; there was no place for this kind of thing in Núñez’s vision for the club. Venables made little effort to keep him, playing the role of a bystander as the Argentine was shipped off to Napoli.

Upstairs downstairs

Instead, the English coach turned his attention to finding a replacement, and in that regard the name on everyone’s lips was Hugo Sánchez, Atlético Madrid’s Mexican goal poacher. But Venables had other ideas, and put in a call to Tottenham to enquire about the availability of their Scottish forward, Steve Archibald.

“I had no interest in coming to play in Spain,” said Archibald in 2013. “I wanted to stay at Tottenham. But the club wanted the money, so I didn’t have too many options.” Archibald’s transfer from Spurs to Barça was a saga that defined the initial stages of the Venables era. In a foreign land so different to his own, Venables went back to what he knew – and what he knew was London. Archibald had led the line with great success for Keith Burkinshaw’s Spurs – a gifted side that had won two FA Cups and a UEFA Cup in the time the Glaswegian was at the club – and found himself at the top of the shortlist when Venables began the drive to replace Maradona.

SEE ALSO Who the hell is Hugo Sanchez?

Though a well-respected, talented forward, he was not the man most Barça fans wanted; for them, it was all about Sánchez. The two footballers even found themselves in the same hotel during transfer negotiations. “He was upstairs, I was downstairs,” remembers Archibald.

Outside the confines of the Nou Camp and Barcelona’s luxury hotels, a media circus had arrived, with every development pored over by a variety of newspapers and magazines. “Who would you sign?” demanded El Mundo Deportivo. In the end, it was Archibald who would wear the blaugrana, with Venables making something of a power play to overrule an agreement that appeared to have been reached between the club and Hugo Sánchez.

Joan Gaspart, the vice-president of Barça, would later claim that a deal had been struck with Sánchez pending the coach’s approval, and that he and Hugo had even celebrated the news with a meal in a Mexican restaurant. After Venables’ apparent veto of the deal, Gaspart was forced to telephone an upset Sánchez with the bad news.

Great Scot

A nonplussed Archibald soon showed up in the papers beside a beaming Núñez, who declared: “Este és el hombre.” This is the man, cried the president, to rid Barça of the unholy spectre of Maradona. The fans, again, were not best pleased, with the Archibald transfer seeming a mere penny-pinching exercise. Núñez’s comment that he “cost seven times less than Maradona” appeared to back up this idea.

But Venables was convinced that Archibald was indeed the man to knit the side together, an opinion that soon spread to the rest of the players. “He really knew how to play without the ball, and that kind of player will be there for his team-mates,” remarked defender Julio Alberto, 20 years later. Archibald was not Maradona but he was still an excellent player, and it wasn’t long before he began to bed in within the squad with his reliable, efficient performances quickly winning over most of the sceptics.

Gradually, though, they became far more artisanal under Venables than they had been under Menotti. Barça rediscovered their identity on the pitch, and by the end of 1984 had firmly laid down a foundation for a title challenge. Venables had turned around the lack of pragmatism that pervaded the Menotti era, bringing in a high-pressing line and prioritising the team over individuals. This was an ideal he reinforced by focusing on bringing through recruits from the cantera, an approach which differentiated him from many of his predecessors, and one that was to have a lasting effect on the club.

His side didn’t play Route One, as many observers in Spain felt they might, but were nevertheless a better organised, better-drilled outfit than they had been previously. It was a style to which 'Archigoles' was infinitely more suited than Maradona – or Hugo Sánchez for that matter.

By the spring of 1985, Barça had wrapped up their first Spanish league title since 1974, four years before the reign of Núñez began. The gamble on the English “Meester” had paid off and Núñez, finally, had his moment. Archibald’s goals and the management of Venables were inseparable from the success, giving the triumph a distinctly British feel.

It was to be a brief honeymoon for the duo, neither of whom were able to follow up this triumph with much further success. Archibald was turfed out of Barcelona on the back of Barça’s signings of Gary Lineker and Mark Hughes, and saw out the remainder of his career in relative mediocrity. Venables went on coach Spurs to an FA Cup win in 1991 and England to a semi-final exit at Euro 1996, but never again won a league title.

Yet, although the career of the “False Messiah” arguably promised more than it delivered – and even though, like Vic Buckingham, Venables passed on the reins to a Dutch master who would catapult the club to greater achievements – it cannot be taken away from El Tel that he took on the Orwellian beast that was Barça in 1984 and, briefly, tamed it.