Zinedine Zidane the Manager: How Zizou positioned himself to lead Real Madrid

The Frenchman was his generation’s greatest player – now he wants to be its greatest coach.

On a late March day, a bald man sits cross-legged on a stone wall in the corner of Bayern Munich’s Sabener Strasse training ground. Squinting slightly, with arms crossed, this wannabe coach studies the Bavarians’ every move intently.

As training ends, Bayern’s perma-permed centre-back Dante bounds over for an opportunistic photo, bypassing World Cup-winner Claude Makelele and ex-Roten full-back Willy Sagnol. A couple of excitable youth-teamers follow suit. Xabi Alonso soon sidles by for a quick chat. Then Franck Ribery.

Even Pep Guardiola, the most revered of tacticians, comes across to say hi. A film crew swiftly descends on this follicly challenged pair, cameras clicking away. Makelele and Sagnol merely look on.

All this for a coaching novice, whose dugout experience comprises one year as an assistant manager plus two-thirds of a season in charge of a third-tier reserve team? Well, yes, but then it isn’t every day that Zinedine Zidane visits your training ground.

Zizou's training

Perez wants a Guardiola type at the Bernabeu more than his next breath. He wants someone in touch with Madridismo, who captures the fans’ imagination

The greatest footballer of his generation is in town to observe Guardiola’s methods as part of the Frenchman’s UEFA Pro Licence coaching course. By the beginning of May, a glowing recommendation from Guardiola under his belt, Zizou proudly announces on Instagram that he’s passed. Everything looks set for Zidane to follow Pep’s path from rearing the reserves to bossing the big boys, following Carlo Ancelotti’s impending dismissal from the Bernabeu.

A few weeks later, however, Blancos president Florentino Perez appoints Rafa Benitez. Zidane would spend another season with Castilla, Real Madrid’s second team. “I would have accepted the offer to replace Ancelotti,” said the 1998 World Cup winner. “But Madrid still don’t think it’s my moment.”

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

In truth, it was never a realistic option. Guardiola, Zidane’s coaching inspiration, swept all before him at Barcelona B in 2007/08 with a stunning brand of football. Castilla hadn’t even made the promotion play-offs in an often-chastening first season for Zidane. Criticism abounded.

Yet Perez wants a Guardiola type at the Bernabeu more than his next breath. He wants someone in touch with Madridismo, who captures the fans’ imagination and is already a legendary figure at the club. He wants Zinedine Zidane.

But can this natural introvert really inspire a group of players? Can he control the temper that resulted in 14 red cards as a player? And, most importantly, could he really afford another season like 2014/15 to succeed on the bench in the way he did on the pitch? After all, patience isn’t exactly a virtue associated with Florentino Perez.

“He spoke with the ball”

I’ve never seen anything like it. Yazid [Zidane’s middle name] had the warrior quality of his impoverished community. He was hungry

Zinedine Zidane has always been loath to admit it, insisting he became a great through hard work, not pre-ordained talent, but this was a footballer whose prodigious gifts were always evident. Yes, it took time – first at Cannes, then Bordeaux – to mature into a World Cup and Champions League winner, but the talent was obvious from an early age.

The fifth child born to Algerian parents Smail and Malika in La Castellane, a working-class Marseille suburb plagued by high unemployment, drug trafficking and prostitution, he first started kicking a ball with his brothers around the Place Tartane beneath the family’s high-rise apartment block.

Jean Varraud, the scout who discovered Zidane and brought him to Cannes, was stunned. “He spoke with the ball,” Varraud once recalled. “I’ve never seen anything like it. Yazid [Zidane’s middle name] had the warrior quality of his impoverished community. He was hungry.”

What followed was a stellar career – the closest thing to art that football has ever produced. By his retirement in 2006, he had won everything: the World Cup, Euro 2000, the Champions League, three league titles and a Ballon d’Or. Yet, much like his managerial idol Guardiola, he had drifted in his last couple of (trophyless) seasons.

Frustration had set in. The headbutt on Marco Materazzi in the closing stages of the 2006 World Cup Final, his last game as a professional, was testament to that.

“When I retired, I didn’t want to be a coach,” recalled Zidane. “I wanted to dedicate myself to something else.”

He became something of a nomad. Still based in Madrid, he visited his parents’ roots in Algeria and invested his time and no little money in a number of charities from Bangladesh to Switzerland. He appeared intermittently on French satellite channel Canal Plus’ football coverage for major tournaments, and was the face of Danone, Adidas and even Lego. But nothing grabbed him.

Come in, coach

Increasingly, Zidane involved himself in day-to-day training, which led to divorce with Mourinho in September 2012

In March 2009, he returned to Real Madrid, initially as an advisor to president Perez. Within a year, he’d replaced Jorge Valdano as sporting director, providing the link between Jose Mourinho’s first team and Perez.

“After everything he’s lived, he couldn’t stay away,” said brother Noureddine. “Something would be missing: the pressure, that anxiety before a match, which can only be regained by being a coach.”

Increasingly, Zidane involved himself in day-to-day training, which led to divorce with Mourinho in September 2012. The Special One wanted another mouthpiece; someone to criticise referees and take part in his “verbal wars”, as daily paper Sport wrote. Zidane wanted to coach. He spent 2012/13 across los Blancos’ youth teams, cajoling, encouraging and helping promising stars Jese and Alvaro Morata with one-on-one sessions.

Above all else, he had missed the dressing room. When Carlo Ancelotti arrived at the Bernabeu in the summer of 2013, Zidane became his assistant. “This is what I want to do,” Zidane beamed, adding that Ancelotti – his former coach at Juventus – was the only man for whom he would act as an assistant. “When I stopped playing I did a lot of things, saw many people, studied a lot of football and did quite a few jobs, but when it comes down to it, you end up going back to what gives you energy – life. You have to do what you love, and for me that’s football.”

He began taking his coaching badges back in France and threw himself into training. He joined in the odd five-a-side, laid out the cones and fastidiously worked in the background, analysing upcoming opponents.

“You certainly couldn’t see it when he was 17 – he was all player,” Guy Lacombe tells FourFourTwo. As Zidane’s first coach in the Cannes academy, and his personal tutor while he took the UEFA Pro Licence, the 60-year-old former Paris Saint-Germain boss is uniquely placed to analyse Zizou the manager.

“What Zidane did already have was the sense of the collective,” he continues. “He made other players play well. He used to solve problems on the pitch intuitively because he was so good, but he also got the best out of his less talented team-mates.

You certainly couldn’t see it when he was 17 – he was all player

“Now he needs more than intuition, but he has this intimate skill to feel the collective thinking of the team. He has always understood other players.”

Lacombe’s point is an important one. The principal criticism levelled at great players going into management is that they can’t understand why their charges can’t repeat what they themselves were capable of. Glenn Hoddle is the frequently cited example. Meanwhile, more limited players such as Mourinho, Arsene Wenger or even current Real Madrid boss Rafa Benitez, can identify more easily with those lacking extreme talent.

Meet the boss

With Zidane yet to complete his UEFA Pro Licence, he wasn’t eligible to lead a Segunda B side

Leaving behind his Ancelotti first-team safety net, Zidane was made Real Madrid Castilla manager in June 2014. Well, sort of. According to the club’s website, academy boss Santiago Sanchez was head coach with the Frenchman technical director, as Madrid anticipated the problem that, with Zidane yet to complete his UEFA Pro Licence, he wasn’t eligible to lead a Segunda B side. Yet anyone who saw Zizou introduce himself individually to the squad on the first day of training in mid-July 2014, then lead Castilla in their opening games, barking orders, making substitutions and constantly cajoling his charges while Sanchez remained passive on the bench, could clearly have seen whose hand was really on the tiller.

This was the good ship Zidane, no doubt – and waters immediately became choppy. Castilla won just one of their first six games, losing 2-1 on the opening day in a Madrid derby defeat at Atletico B, having led 1-0, as Zidane struggled to find his best team and a tactical structure that suited his players. For perhaps the first time in his football life, Zidane’s will couldn’t alter the course of a match.

“The first time I went to see him, he was timid in training and couldn’t take charge of the group,” says mentor Lacombe. “Fifteen days later, he was much more assured – but they still weren’t winning games.”

A confirmed football aesthete (“I want my team to play, spread the ball, build from the back and keep possession”), Zidane – and Lacombe – soon found the solution. He took into account his players’ limitations.

“We realised that he needed to change the style of play,” Lacombe tells FFT, “moving from a possession-based game to something more direct and more efficient.”

The change worked. Set up in a 4-2-3-1 system that would remain for the rest of the season, Castilla won 37 of 48 points available from mid-October and were top by January. Guillermo Varela – the on-loan Manchester United right-back whose signing Zidane had personally demanded – excelled in defence, captain Sergio Aguza brought calm assurance in midfield and joint-top scorer Raul de Tomas provided the cutting edge.

Storm before the calm

Spain’s regulations are stricter than even UEFA’s, and he received much support. ‘Let him work!’ screamed the front page of the following day’s L’Equipe

Halfway through that run, the Spanish coaching federation had finally addressed the elephant in the Zidane coaching room. President Miguel Angel Galan demanded Zidane’s suspension until he had attained the required badges, regardless of his official job title. Spain’s Competition Committee agreed and banned the Castilla boss for three months.

Things got ugly. Zidane accused Galan of “jealousy” and reasoned he could have achieved the UEFA Pro Licence in Spain in “30 days” but had chosen to do it in France. The latter responded that the Frenchman’s tone was “worrying and arrogant”.

Zidane, however, had a point, because each country’s rules on qualifications differ. Spain has a fast-track system for world-class ex-pros such as Zidane, but he preferred the three-year classroom environment of the French system. Indeed, Spain’s regulations are stricter than even UEFA’s, and he received much support. “Let him work!” screamed the front page of the following day’s L’Equipe. Others waded in.

“The fact is that Zidane, with the titles he won as a player,” said Francois Blaquart, technical director of the French FA, “is qualified to coach Real Madrid in the Champions League, but not Castilla in Segunda B. That’s the paradox of the system.”

Lacombe agrees, citing Remi Garde as an example; Garde managed Lyon in Ligue 1 and the Europa League with the same qualification deficit. “Yazid is a victim of his own good intentions,” says Lacombe. “He could’ve found work at any club by using his fame, but he decided to put himself naked at the Madrid cantera. This is a wonderful thing he’s doing.”

Even Johan Cruyff, the great Barcelona mouthpiece, spoke out in support of Zidane. Cruyff had been in a similar situation throughout his eight years as Barcelona boss from 1988. He had no qualifications, so officially Charly Rexach was manager to Cruyff’s technical director, to circumvent Spanish football law. “It’s ridiculous,” said the Dutchman. “I’d much prefer a good coach without their badges than a bad one with them who hasn’t got a clue.”

Teenage problems

It’s normal that the arrival of a 16-year-old with the sort of salary like his [a reported £80,000 a week] will affect the atmosphere in the dressing room

Real Madrid appealed the decision in the Spanish courts and won, but another controversy was around the corner, this time on the pitch. With Castilla top of the league, Florentino Perez bought wunderkind Martin Odegaard from Stromsgodset, a month after his 16th birthday.

The Norwegian’s arrival coincided with a dip in Castilla’s form, amid rumours he insisted on training with the first team during the week (at Perez’s behest), while playing with the reserves at the weekend. Animosity swiftly grew, yet Zidane dealt with the problems well.

In a club where political dicta influence team selection, Zidane stood his ground impressively, dropping Odegaard when merited. “It’s normal that the arrival of a 16-year-old with the sort of salary like his [a reported £80,000 a week] will affect the atmosphere in the dressing room, especially when other players will have spent up to 10 years at the club,” Ruben Jimenez, Spanish sports daily Marca’s Castilla correspondent, tells FFT. “Odegaard is very good and will become even better. He should stay with Castilla and grow, so as to improve with Zidane as his teacher.”

Thore Haugstad, a Norwegian journalist who watched each of Odegaard’s 11 Castilla games last term, agrees. “It can certainly be seen as a smaller version of the ‘preferences’ that Perez sometimes makes clear to the first-team coach,” he tells FFT. “Towards the end of the season, Zidane gave Odegaard a role in which he plays as a central midfielder in a 4-3-3 when Castilla have the ball, and as an attacking midfielder in a 4-2-3-1 when they defend. This has worked, and reflects well on Zidane’s tactical acumen.”

RECOMMENDED The truth about Martin Odegaard's first season at Real Madrid

Yet neither that tactical acumen nor Zidane’s political manoeuvrings could prevent Castilla’s season petering out to a sixth-place finish in the third tier, outside the play-offs. While Pep Guardiola’s Barcelona B had surged to promotion from the same division in 2008, Zidane’s Castilla limped home. By the time Benitez’s appointment was confirmed in early June, it was no surprise that Zidane would spend another season with the reserves.

“At Real Madrid, any time you don’t achieve your objectives is a disappointment, and obviously the team was there for them to have been a lot closer to promotion,” says Marca reporter Jimenez. “They weren’t quite as good as the era of Jese or Alvaro Morata, perhaps, but there were players with great quality like Alvaro Medran or Burgui in attack, or Diego Llorente in defence.”

Worryingly, Medran, Burgui and Llorente are spending 2015/16 out on loan at La Liga sides Getafe, Espanyol and Rayo Vallecano respectively, while captain and midfield string-puller Sergio Aguza went to MK Dons permanently and still hasn't featured in the league. His replacement as skipper? Enzo Fernandez: Zidane’s son.

“If you’re soft, it doesn’t work”

I discovered that, for the common good, you have to know how to tell players things they’re not ready to hear

To succeed in the dugout, Zidane has had to evolve his own psyche.

A natural introvert, he has never been the sort to lead from the front, making it easy to mistake shyness for arrogance. “Zidane playing in a team,” French singer-songwriter Jean-Louis Murat once mused, “is like putting Jimi Hendrix into a band and when you tell him he’s the lead singer, he says he’d prefer to play the maracas.”

While that may be an exaggeration, Zidane has undoubtedly had to come out of his shell. “If you’re soft with the boys, it doesn’t work,” he told France Football in a rare interview in June. “I discovered that, for the common good, you have to know how to tell players things they’re not ready to hear.

“I do it rarely, because I think I have a natural authority which means I don’t have to resort to bawling out players. If I yelled the whole time, I wouldn’t be myself. You’re going to tell me that a coach has to talk much more than I do, but that’s not the case.”

Crucially, Zidane keeps these rare displays of emotion confined to the dressing room. The public display of humiliation for a misplaced pass or fluffed chance isn’t for him.

“He doesn’t shout all that much,” says Marca's Jimenez. “Sometimes he gets angry, but more than anything else he gives constant instruction. Seriously, the whole game. If he does get angry with his players, he doesn’t show it. It’s more a constant dialogue of instructions to play the way he wants.

“I understand he likes to control everything that happens – again, constantly talking – but the press aren’t allowed to attend training.”

Zidane the introvert

He was aware that extra work was needed, and not just with the media, but in communication with executives, players and fans

Among the criticisms of Zidane last season, his first, this is the biggest. Because he won’t talk about his lack of coaching badges, the rumours of post-game misdemeanours and poor substitutions, he creates a vacuum which sucks in speculation and creates extra column inches.

True, Zidane clearly wants to let his coaching do the talking, but the feeling is that if he did explain his methods, how he trains the team or his in-game decisions, his message would be far stronger. As it is, Zidane hasn’t given a single press conference as Castilla boss.

Zidane’s attitude is effectively the anti-Pep. He gives one-on-one interviews on a semi-regular basis, which Guardiola refuses to do, but doesn’t give press conferences. For his part, Zidane is aware that he cannot allow his introspection to cloud his relationship with the media.

“We’ve talked about it a lot and even did some media training,” mentor Lacombe reveals to FFT. “He was aware that extra work was needed, and not just with the media, but in communication with executives, players and fans.

“He was surrounded by some masters in Madrid. Carlo Ancelotti and Jose Mourinho are different, but deal with the media very well. Zidane will be Zidane. He’s no loudspeaker. But he’ll do the job.”

Yet Zidane has practice in managing aspects of his personality for the greater good. As a player, his 14 career red cards served notice of his spiky personality, but a manager must display a certain serenity. “Sometimes you can see the tension in my eyes,” Zidane has admitted. “During games I suffer a lot as a manager, much more than I did as a player. It’s not all that bad as a player. [But] when you’re on the bench and the game starts, there’s nothing you can do.

During games I suffer a lot as a manager, much more than I did as a player

“I’m a person like any other, and inside me I felt like a volcano a lot of the time that wasn’t easy to manage.”

But manage it he has. Those who watched Castilla last season have been impressed at how dormant that volcano has remained. “There was Zidane, the player on the pitch, and Zidane the person,” Lacombe tells FFT. In 1988 at Cannes, he gave a teenage Zidane a one-month ban for punching an opponent who had fouled him, one of several flashpoints involving the midfielder before he had even broken into the first team.

“He learned to play football on the Marseille streets, where strong local area rivalries exist,” says Lacombe. “You represent your piece of the city. If you don’t react, if you don’t show who’s the boss, you just don’t exist.

“That is Zidane the player. Zidane the coach will be like Zidane the man.”

If that legendary temper can be harnessed, his openness with the media will surely follow.

The Responsible One

When you’re an assistant you can advise, bring a different opinion to the coach’s, but it’s not comparable to being in charge

Yet for all the criticisms, there is one evident strength to Zidane the coach – his unshakable will to be one, and to succeed at it. He doesn’t need the money, nor does he need the grief.

“As the manager, you’re the one who’s responsible,” Zidane said in June. “To be a [head] coach is to be alone. When you’re an assistant you can advise, bring a different opinion to the coach’s, but it’s not comparable to being in charge. You have to live it to notice that change.

“It comes at you from all angles. One day it’s an injured player; the next, it’s someone who can’t train because they have a personal problem; the day after, it’s the pitch. Every day you have 15 or 20 things to look after as well as working with your team. It’s not necessarily a pain – it’s part of the job.”

Lacombe has seen this desire first hand. “Every coach I know believes in him,” he says. “His behaviour proves his seriousness to his work. He’s there every morning at 8:30am. He’s there until late in the evening. He’s always on the phone or chatting with his assistants about how his team can improve. That’s really impressive. It’s a huge blessing that such a champion wants to give back to the game.”

It isn’t just Zidane’s will to succeed that has impressed Lacombe during the pair’s three-year coaching alliance, though. Indeed, Zizou’s mentor believes that his pupil’s natural introspection is among his biggest positives.

“He’s a great listener,” Lacombe tells FFT. “I can tell you that’s pretty rare among former players. He listens more than he sees, and as a result he’s learned from every coach he’s had.”

Lacombe isn’t the only one to notice Zidane’s primary coaching strength. Before Zizou’s Castilla appointment last summer, Bordeaux president Jean-Louis Triaud tried to entice the club’s most famous son back to south-west France, where he spent four years.

Bordeaux didn’t happen because we couldn’t build the team he wanted. We couldn’t spend what he wanted

“It was a serious option for one long month,” he tells FFT. “It didn’t happen because we couldn’t build the team he wanted. We couldn’t spend what he wanted. He was very ambitious. If he spends time on something, his goal is to win.”

Why Zidane?

“Instinct. It was the same for Laurent Blanc in 2007. Zidane was a great player – he’s not exactly the grocer next door. We knew his qualities. We knew the man. We knew his preparation for the job. We knew how deeply he involves himself in everything he does. And we knew he doesn’t really need to do it to make a living; it’s because he really wants it. Is that good enough for you?”

Go with the Flo

Yes, it can be difficult to get any words out of him, but he’s very firm and constant, with huge footballing knowledge

It’s certainly good enough for Florentino Perez. Part of the reason why the Bordeaux move broke down was because the Real Madrid president convinced his favourite Galactico to stay at Valdebebas. In Zidane, Perez sees a born winner.

“Logically, Zizou can only be a head coach,” Perez said last year. “It’s impossible for him to be a No.2. When he started out as a player, he knew the route to become the best in the world. In the same way, he’s convinced he needs time to become that good as a coach.

“Yes, it can be difficult to get any words out of him, but he’s very firm and constant, with huge footballing knowledge. These are the qualities any great coach has.”

In Perez, Zidane sees a father figure, someone without whom his life would be immeasurably different. “Perez changed everything,” he said in 2013. “He’s the reason I’m here. Without him, I wouldn’t have scored the goal that won la Novena [Madrid’s ninth European Cup in 2002, with that volley against Bayer Leverkusen in the final]. He’s given me everything and I want to repay that as coach.”

RECOMMENDED FourFourTwo's 20 best Champions League and European Cup goals of all time

Returning to Marseille, the city where he was born and bred, may yet prove impossible to resist, but given the strength of the Perez-Zidane relationship you would expect the latter to stay in Madrid. After a trophyless 2014/15, there is a debt to be repaid.

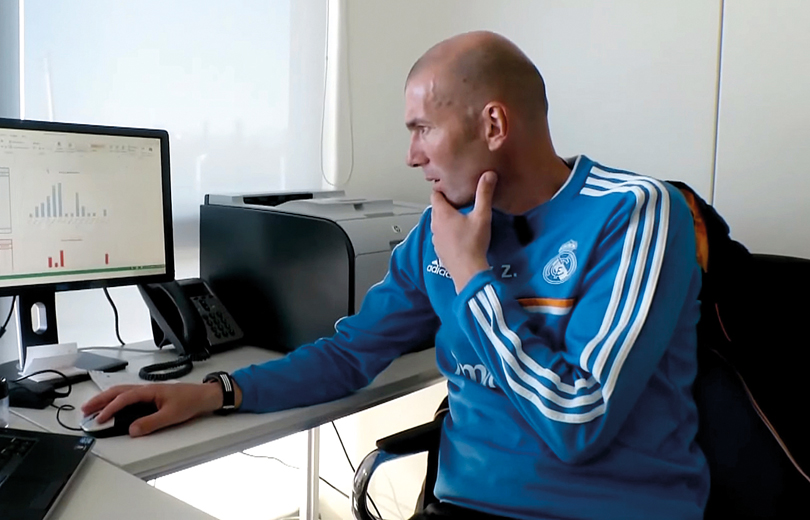

Crucially, Zidane’s style and attention to detail behind the scenes has won him admirers as well as time. As soon as his club Audi enters Valdebebas every morning, the Frenchman heads straight to his minimalist white office, the same workspace he had as Ancelotti’s assistant. Although he has a sofa and two easy chairs on one side of the room, they’re seldom used.

Dressed in his training gear (the unique initials ‘ZZ’ stand out like a trademark) instead of his snug-fit matchday suit, Zidane will immediately sit at his L-shaped desk and connect his laptop to a second screen. Together with his assistant David Bettoni, he spends his week analysing future opponents and calling up graphs that show when and how his team concede goals, as well as videos.

The pair have been inseparable since they were wide-eyed youth teamers at Cannes. Within minutes of meeting in 1988, they were racing a rusting Ford Fiesta (Bettoni) and a battered Renault Clio (Zidane) from Cannes to Marseille. When Zidane moved to Juventus in 1996, he persuaded the Old Lady to find a semi-pro club in the area for Bettoni.

Also bald, but a good foot shorter than his illustrious friend, Bettoni acts as a sounding board from across the other side of the desk. ‘Davi’ has a smiley, talkative demeanour and provides the get-up-and-go drive that Zidane doesn’t naturally emit.

Castilla conundrum

In June, Perez abolished Real Madrid C, the thinking being that the president only wants players at the club who are capable of playing for the first team

Out on the training pitch, Zidane is no different. He allows Bettoni – himself a UEFA Pro Licence holder who used to head up the Cannes academy – to lead group sessions, while he intervenes one-on-one as he sees fit. They dovetail brilliantly – a modern-day Brian Clough and Peter Taylor.

Last season, Burgui was the recipient of this one-on-one tuition; in 2015/16 it's 18-year-old Borja Mayoral, Real Madrid’s next great hope who won the Golden Boot in Spain’s Under-19 European Championship-winning team. “Zidane,” Ancelotti said in early 2014, “is always doing something.” For the first time ever last season, Castilla chartered flights to away games – on Zidane’s expressed demand.

Whisper it, but this is a Guardiola-esque level of attention to detail. This season, he’s needed it: the 2015/16 Castilla is among the youngest in its history. In June, Perez abolished Real Madrid C (a team made up of players too old for the youth teams but not good enough for Castilla), the thinking being that the president only wants players at the club who are capable of playing for the first team.

It appeared to be a positive for Zidane – he’s got more players available, having struggled with injuries last term – but everything isn’t quite rosy. Castilla has always survived by blending promising youngsters with two or three 24-year-olds with first-team experience lower down the Spanish pyramid. They sign knowing they’ll never play first-team football for Real Madrid, but want to be around the club and help the next generation to develop. The departed Aguza was a prime example. This season, Zidane’s team has effectively been 22 and under (including his 20-year-old playmaking son Enzo) and without Medran, Burgui, Llorente and Varela, as well as Aguza.

“The new Castilla is a complicated case,” confirms Marca journalist Jimenez, “because players have left, so they’re very young lads and with much less experience than previous years, but they’ll still have the same obligation of fighting to go up. This time, Zidane has to deliver.”

Excellence as standard

I have to be good; I have to win. But I have no concerns over that. If I did, I would have gone fishing

This time he is. Eighteen games into the current season, Castilla are second in their winter break, five points behind leaders Barakaldo but with a six-point cushion in the play-offs. Twenty-two-year-old Dominican Republic international Mariano Diaz is the league's top scorer with 11 goals, having featured far more regularly this time around.

Before the season, Zidane knew this was his biggest season yet. “People demand excellence, but that’s as it was on the pitch,” he said in the summer. “I know the rules. I have to be good; I have to win. But I have no concerns over that. If I did, I would have gone fishing.”

Mentor Lacombe certainly believes his most famous pupil is up to the task. Last season’s struggles for form and brushes with coaching law can only help his progression. “He learned how tough this job could be,” he tells FFT. “He had to let it happen. It’s better for him to go through something like that very early in his career.

“The Zidane of the beginning of last season is very different from the Zidane at the end. He made a lot of progress. That year he needed to be stronger; to know his players better. Like every coach, he will need luck and a sense of destiny.”

When, not if

Having Monsieur Zidane there right next to me to listen to me was an unforgettable moment. What’s more, he was grateful to listen to me

The France 98 brace of headers, the 2002 Champions League Final volley, the Marco Materazzi headbutt – destiny has always followed Zidane. His name carries weight, which goes a long way in the dressing room.

“He has natural charisma when he walks into a room,” his friend, fashion designer Jacques Bungert, once said. “Perhaps because he is Zidane, but also because he is the man he is – because he has this internal strength, this presence – he imposes something. He creates something. That’s who he is.”

The influence Zidane’s presence can have isn’t limited to starry-eyed youth teamers or his friends. The Frenchman played a crucial role in Karim Benzema extending his Real Madrid contract 18 months ago. Indeed, los Blancos’ No.9 has gone on record as saying it would be a dream to play for Zidane at the Bernabeu.

The power of the Zidane name isn’t even limited to players. When he visited Marseille last December, then-manager Marcelo Bielsa – himself one of the most revered and influential coaches in world football and 17 years his senior – was “like a kid” at meeting his Castilla counterpart.

“Zidane is a living football monument,” gushed the Argentine tactician. “Having Monsieur Zidane there right next to me to listen to me was an unforgettable moment. What’s more, he was grateful to listen to me. Zidane exercises this inhibitive power on common mortals. It’s indescribable.”

Inspiring respect in the dressing room may be about more than just showing off your playing medals – just ask Ruud Gullit, Lothar Matthaus or Diego Maradona – but starting from that position is valuable for any coaching novice such as Zidane.

When Zidane visited Bayern Munich’s training ground back in March, he witnessed three 90-minute sessions that featured constant ball work and extensive drills to establish numerical superiority in possession. “Bayern’s game was already fast and attacking,” he said, “but Pep has taken it to the next level with that hint of genius. I love watching to see how he works. He inspires me.”

Armed with new ideas, the necessary coaching badges and the love of a powerful man in Perez, Zidane the coach is refreshed and determined to succeed, even if he was passed over for that gilded top job last summer. “I want to build something,” says the greatest footballer of his generation, who wants no less an epithet in the dugout. “I want people to say: ‘What you did as a coach... not bad. Not bad.’”

Zinedine Zidane’s time has come. Pep, you have been warned.

Additional reporting: Ben Lyttleton and Alison Ratcliffe.

This feature originally appeared in the October 2015 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe!

Andrew Murray is a freelance journalist, who regularly contributes to both the FourFourTwo magazine and website. Formerly a senior staff writer at FFT and a fluent Spanish speaker, he has interviewed major names such as Virgil van Dijk, Mohamed Salah, Sergio Aguero and Xavi. He was also named PPA New Consumer Journalist of the Year 2015.