The big interview: Dennis Bergkamp – "I never expected to be at Arsenal for 11 years"

Could he have joined Barcelona? Did his fear of flying affect his football? And who'd win in a one-on-on: him or Henry? We grabbed the "non-flying" Dutchman in February 2011 to find out

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

It's perfect weather for an encounter with 'The Iceman'. The land is covered in powdery snow, it's seven below zero and north Holland's canals are frozen thick. Beside the IJsselmeer, the effect of an icy Siberian wind whipping into your face is like being thumped in the face with hammers. The cold snap has forced Ajax to cancel today's youth team training, so the club's legendary under-12s coach has agreed to meet us at a cosy cafe in the village of Baricum about 30 kilometres outside Amsterdam.

As Dennis Bergkamp talks candidly about his ideals, his career and his greatest goals and passes, you realise the nickname doesn't fit at all. The Arsenal and Holland great is warm, intelligent, passionate, gracious and modest. And the feeling you get talking to him is remarkably like the one you had watching him play: you come away strangely enriched. Hopefully you'll feel the same way...

Who were your footballing heroes when you were growing up?

Amanda Nixon, via email

I admired Glenn Hoddle. He stood out because of his technique: two feet, a soft touch, very precise. At Ajax, Johan Cruyff was the first-team coach. One evening he came to our training ground and took a session – that was really intimidating. A big name like that coaching 12-year-olds! But he talked to me in a very relaxing way: "Just play your game, enjoy it." Later, he guided me into the first team. Others at the club said I wasn't strong or aggressive enough, but he said: "Just look at the talent."

What was your reaction when you found out Ajax wanted to pick you up at the age of 12?

Tommy McManaman, via email

They first asked when I was 11, but my parents, who are very down-to-earth people, thought Ajax was all fur coats and big mouths so they said: "It's not you; just enjoy the football." A year later, Ajax asked again. This time there was another boy from the area to go with. Once we got to Ajax we found it had all changed. The youth development was less systematic then: it was just enjoying football twice a week. It wasn't difficult to adapt. Of course you have to win every game, and it's a different mentality to what I was used to, but it wasn't so rigorous.

How were you so calm under pressure: was it years of training or just your demeanour?

Karabo Mogudi, via Facebook

I am quite focused. And I don't show my emotions to everyone – only people I work with and family. I was never nervous. I always tried to stay at one level: the good things weren't that good, and the bad things weren't that bad. Now I tell the boys I'm training: "Play with a smile on your face." And they say: "You didn't!" When I played I was so concentrated it looked like I was ice cold. But inside I was really happy.

A hundred-odd goals, top scorer in the Dutch league for three seasons in a row... you went from being a great goalscorer at Ajax to a scorer of great goals for the rest of your career. What changed?

Olly Parker, Birmingham

My role changed. At Ajax you knew you'd get five chances a game. At Inter you were lucky if you got one. And at Arsenal I was always more comfortable playing behind a striker, just outside the box. It wasn't my quality to go in the box at the right time and tap in. I was always amazed by players like Ian Wright. He was unbelievable at that.

How did it feel to finish joint top scorer in your first major tournament at Euro '92? Did you feel you'd finally 'arrived'?

Jackie Addison, London

The team had won in '88 and I joined just after the 1990 World Cup, which was a flop. I felt I wanted to fit in; give my best. For me, that tournament was just a case of 'doing my bit'. I scored against Germany and Scotland, and made some crucial goals. I thought: they can't complain. But if you compare it to success with Ajax, it's another step up.

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

I heard Johan Cruyff tried to persuade you not to join Inter. Why?

Alan Eaves, Middlesbrough

He never said it in so many words, but he wanted me to join him at Barcelona. He kept telling me all the teams not to go to, leaving Barcelona as the only one left! I always had the feeling I'd go to Italy, the biggest league at the time. I didn't want to go to Milan because Gullit, Van Basten and Rijkaard had gone there. It came down to Juventus or Inter. We had a better feeling from the people at Inter. They made a lot of promises – which I found out later was something they did a lot. They said: "We're going to play more offensive." They did, but only for the first month! It wasn't what I'd hoped for. But Italy was good for my development. I learned to be more professional, learned to play against two or three defenders, and to play with players who are there for themselves rather than for the team.

What were the issues between you and your team-mates at Inter?

Jim Gervais, via email

Actually, I got on well with them. There were a few players who'd been there for 10 or 15 years – guys like Bergomi, Ferri and Battistini were Inter, and they were all really nice to me. I had a good relationship with Nicola Berti too. He's a good guy. I never had a problem with anyone. The only thing I was disappointed with was Ruben Sosa: we could have got more out of each other on the pitch, because we were the two strikers. Maybe he resented me a little but we never clicked on the pitch. Off the pitch we had no problems at all.

How did you feel when part of the Italian media renamed their 'Donkey of the Week' award 'Bergkamp of the Week'? Did you find the English press easier than the Italian media?

Alex Feakes, Southampton

They expected me to talk to them every day in detail! I said: "If there's a game on Sunday, of course on Monday I'll talk to you about the game. But I'm not going to talk again about it on Tuesday and Wednesday. So I'll talk to the media twice a week, which is a lot compared to England, and even more compared to Holland." But they were angry. They wanted me to talk all the time, and I said no. I need my private life as well, and in England the press respect that. The English tabloids criticised me at first when I didn't score in my first seven or eight games. Fair enough. I never mind if people hammer me about football. But in Italy they made up ridiculous stories. One time I had a haircut and they said my hair was falling out because I couldn't cope!

I seem to remember that Massimo Moratti famously said to Bruce Rioch: "You'll be lucky if Bergkamp scores 10 goals for you!" How much did those words spur you on?

Ron Stockbridge, Northampton

I'm surprised to hear that, because I got on really well with him, he loves football and he was sorry to see me go. At the end of my second year at Inter, he said: "There will be changes – please stay." I decided I didn't want to wait. But there were no bad feelings.

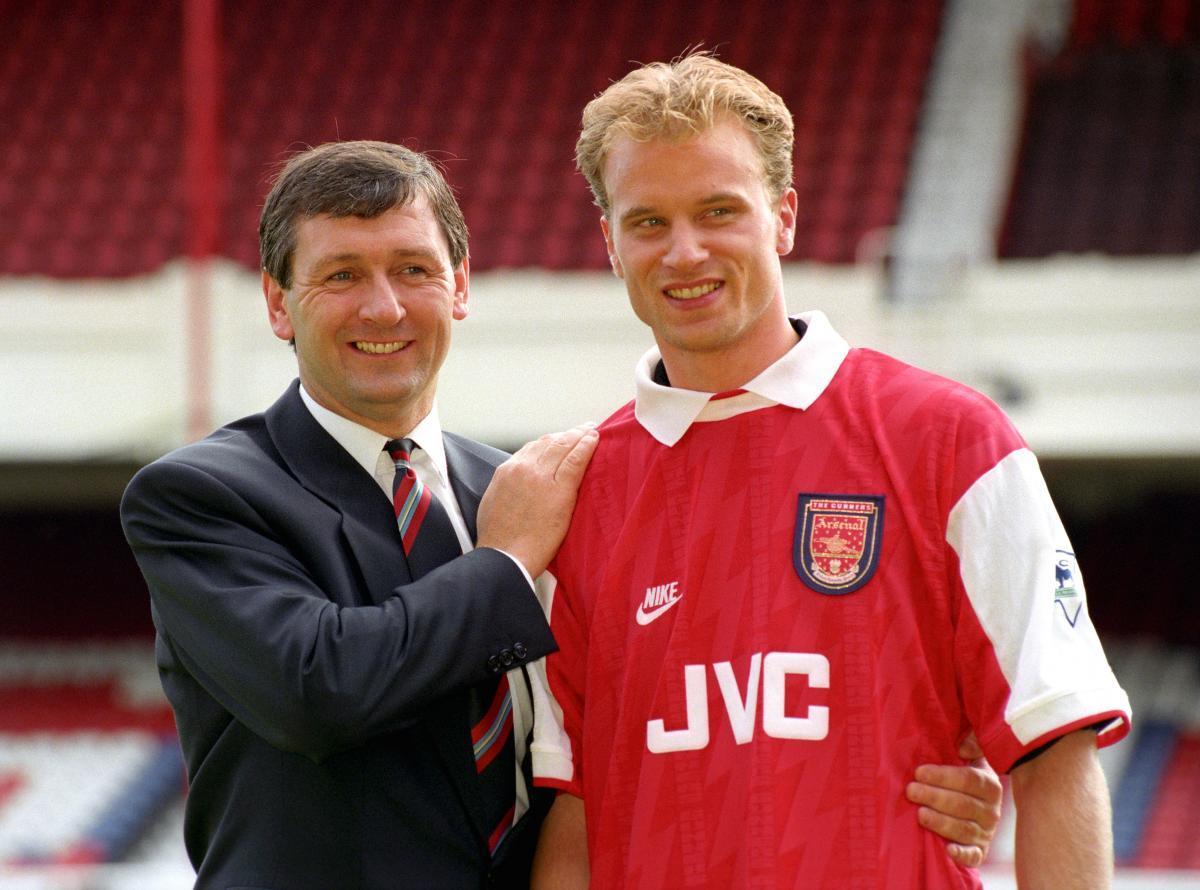

If your family followed Manchester United when you were young, and your favourite player growing up was Glenn Hoddle, why on earth did you join Arsenal?

Jonathan Bowen, via email

My father was a Denis Law fan, not a Manchester United fan. And I wasn't a Tottenham fan; I was a Hoddle fan. My plan was always to come to England after Italy. I loved the passion, the crowds. My agent knew David Dein because Glenn Helder was at Arsenal, and they came on the phone. Bruce Rioch and Dein made a lot of promises; talked about playing in a more attacking way. I couldn't take that seriously because of the Inter experience. But I thought: Arsenal? OK. They'd won the Cup Winners' Cup, they had Ian Wright, they had a settled team with eight or nine who always played. It felt stable, and I thought: "That suits me. It's a big club and it's the way I want to play football. And Highbury is nice. Let's see what happens." I never expected to be there 11 years, but from day one it was exactly how I wanted it to be.

Arsenal was famous for having a big drinking culture in the '90s with the likes of Tony Adams, Paul Merson and Ray Parlour – was that a bit of a shock?

Andy Edwards, London

It was something I just couldn't understand! Pre-season we went to a training camp in Sweden and trained twice a day. In the evening I went for a walk with my wife and saw all the Arsenal players sitting outside a pub. I thought it was unbelievable. The funny thing is you never noticed it in training because they were so strong and they always gave 100 per cent. I didn't drink, and they respected me. They did, and I thought: 'It's part of England so you've got to respect that.'

The next year Arsene came and it all changed. Later, we were successful because of our English defenders. They put the spirit in the team, which the Europeans lacked. They would say, "Get stuck in!" and all sorts of other phrases. I loved it, especially: "How much do you want it?" I thought about it. It stuck with me. Do you really want it more than the opponent? How much are you prepared to give? How much time do you want to put in to become better? It's the English warrior tradition; a moral code. We go out together and we're going to give 100 per cent.

You were a bit of an assist machine at Arsenal: are there any that stick out? How about that pass to Freddie Ljungberg against Juventus at Highbury, when you beat two players and dinked it over the top?

Anita Johnson, London

That was my favourite, though it was not like me to have the ball at my feet all that time. I was waiting for Freddie to make his run. At that time he was always coming from somewhere and I could find him. I remember a lot of assists with Ashley Cole as well. I'd see him out of the corner of my eye. He'd begin to move. If he stops, it's a silly pass, but he'd keep running, because he knew what I was going to do and I'd put it just outside the far post, inside the box, and he would just come across with pace.

You can't defend that. There hasn't been a right-winger born who'll track back that far! You can compare it to a quarterback: you want to see and play the perfect pass. The pleasure of scoring goals is known, but for me the pleasure of the assist came close. It's like solving a puzzle. I always had a picture in my head of how things would look two or three seconds later. I could calculate it. There's a tremendous pleasure in doing something that someone else couldn't see.

Were you worried for your place in the team when Bruce Rioch left Arsenal at the end of your first season?

Arthur Potts, Halifax

At that age, with the way I was playing, I was never worried about my place. When Bruce left I was worried about the Italian syndrome happening again. We had a good pre-season with Bruce and suddenly – bang – he's gone. I didn't know what to expect. Then I heard Arsene Wenger was coming in and I knew his reputation. That did calm me down, because I knew the way he liked to play at Monaco.

Your hat-trick goal against Leicester in 1997, the winner against Argentina in the 1998 World Cup quarter-final, the flick and finish against Newcastle in 2002 – which was best?

James Jones, London

The goal against Argentina is my top goal. To score like that, in my style, on that stage. I love nice football but it has to mean something, and that got us to the World Cup semi-final. My reaction after the goal was emotional because I remembered the dreams of the World Cup I had when I was seven or eight. How did I do it? First, there's eye contact with Frank de Boer – he's going to give the ball. Then: sprint away, get six yards away from the defender. The ball is coming over my shoulder. I run in a straight line, jump up to meet the ball, kill it dead. The second touch turns inside, to make sure [Roberto] Ayala is gone, and get a better angle on goal. I aim for the far post and let it curve in.

After the second touch I know this can't go wrong. No chance! You give absolutely everything, like your life is leading up to this moment. As for the one against Newcastle, my first thought was: "I'm going to do whatever it takes to go to the goal." Ten yards before the ball arrived, I made my decision to turn the defender. The Leicester goal was pure, but there was luck with the Newcastle one. Against Leicester, when the pass came I knew what I wanted to do: control, ball inside, finish.

With all the players Holland had in the '90s, how disappointed were you not to win anything? What was the biggest problem: the coaches, the players or the team spirit?

Pat Dixon, Rochdale

In 1992 we were very close, but we had a team coming to its end. Did they want it enough? What would they achieve? To be European champions – again? They could have been hungrier. If only we'd taken an extra step, we would have been there easily. In 1994, the World Cup was a fantastic experience, but in the end I felt we were just not good enough to win it. But we definitely shouldn't have lost to Brazil. We were better than them. In 1996, well, we know the problems. All the problems, the Ajax players brought into the team. But in 1998 we really should have won. We were the best team. We should have beaten Brazil, and we would have given France a really good game in the final. They didn't want to play us, from what I understand.

And the same in 2000 with the European Championship: we should have beaten Italy easily and got to the final. In Holland we practise penalties all the time now! So in the end, we had really good players, but we couldn't go that extra step. Sometimes I feel we needed a bit less similarity. We were all technical players, all thinking, passing and playing in a good way. But sometimes you need a defender who just puts it in the stand! And up front as well – be more clinical.

Would you prefer Holland to win the World Cup playing dirty or lose playing Total Football?

Chris Gallery, via Twitter

The World Cup Final leaves a bad taste because Holland played such good football leading up to the tournament, in the traditional Dutch way – attacking. They even did it in the tournament a bit. And in 2008 they played that way against Italy and France. So that team had a lot of potential, and somehow they forgot to play football against Spain. Tackles became more important, which we've never been good at. It's just not our thing to play dirty, and we shouldn't have done that. It was probably the frustration of not getting into playing our own game. Knowing Frank [De Boer] and Phillip [Cocu] and [Bert] Van Marwijk, I'm sure it wasn't planned. It's just not their style. Phillip told me it wasn't intentional. But I felt a little bit embarrassed. It's not really Dutch, is it? There are two great footballing nations and one is trying to play football and the other one is preventing them from playing football in a way they've never done before.

Do you think your fear of flying ever affected your ability to play? Surely long journeys in cars and on boats were very draining?

Ben Welch, FourFourTwo Performance writer

It was the opposite. When I stopped flying it freed me. Three days before a game I'd worry about the next flight. During a game I'd be thinking about the flight back. It was stopping me from enjoying football so I had to make a decision either to go into therapy for months or years, or just cut out flying. Everybody accepted it. When I joined Arsenal, almost the first thing that came up in the contract meeting was me saying I'm not going to fly, but I can drive everywhere. It was never a problem.

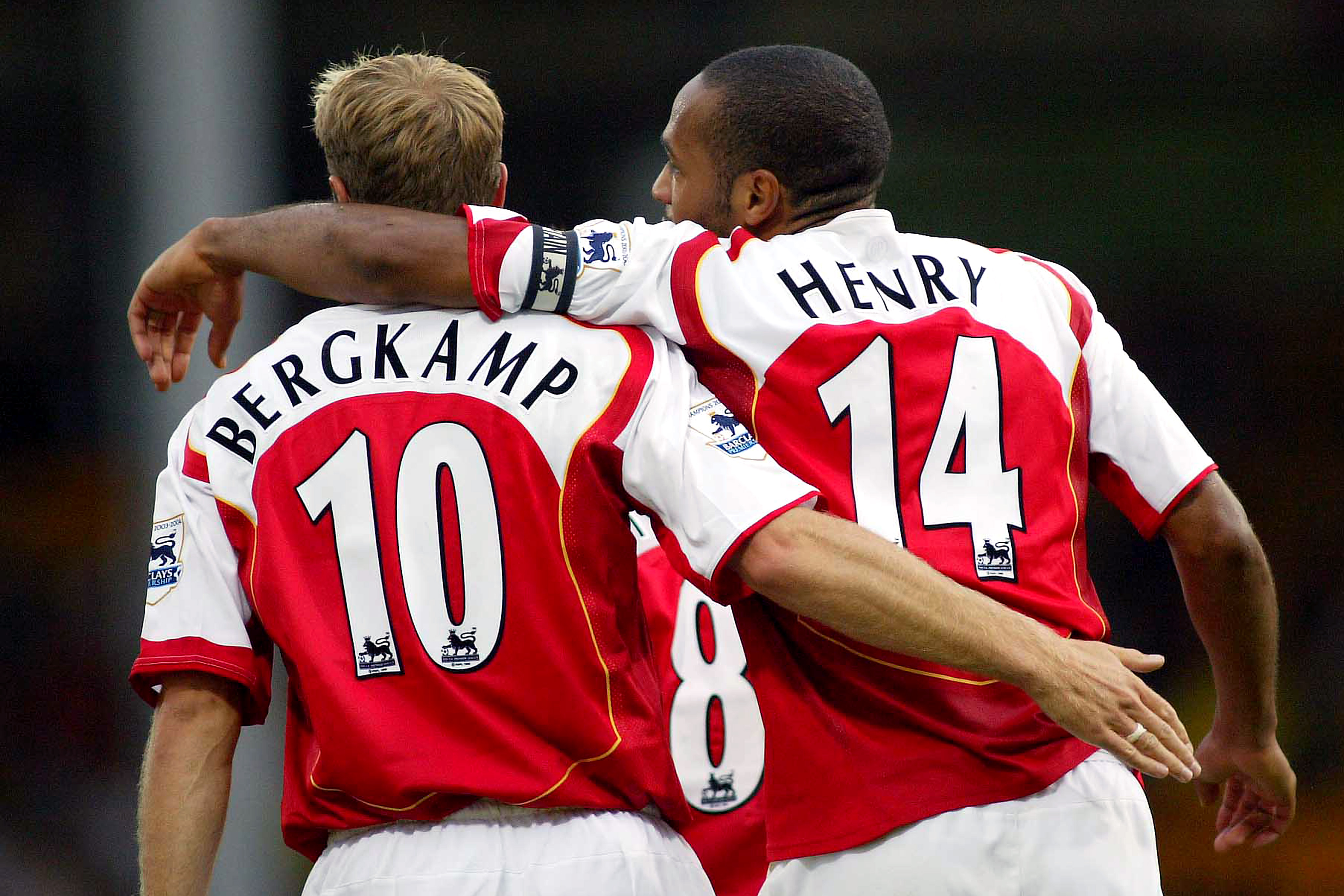

Which strike partner did you most enjoying playing with – Van Basten, Henry, Kluivert, Wright, Anelka – and who was the best?

Darren Johnson, Michigan, USA

For me it was always a matter of adjusting to someone else's game. With Nicolas Anelka it was easy because he was so quick. Just go behind the defender, I'll give you the ball and you're one-on-one with the goalkeeper. Thierry Henry's fantastic with all his skills. And Ian Wright was great. But if I had to pick one I would say Thierry because of the unbeaten season with him. There's a difference between skills and functional skills. Thierry's skills were perfectly functional. There was something behind every movement: to get a strike, receive a pass. Marco van Basten has a different skill. He was a great finisher and had some great touches as well. It's difficult to decide. But I would say Thierry because I worked with him longer in training and we really had a partnership.

Who was the best defender you ever played against?

Robert Frumkin, via email

I think the best are players like Sol Campbell, Jaap Stam – hard, serious defenders with pace who can read the game. I always loved to play against players like [Sinisa] Mihajlovic or [Marco] Materazzi – players with a big mouth who make dirty tackles, step on your toes and give you an elbow off the ball when no one was watching. That got me going. You'd really try to have a good game against those players, and against defenders in general who would have an air like: "Look at me, I'm fantastic." I can't stand that. I prefer defenders like Martin Keown who do their job and maybe have big mouths in the dressing room but in a funny way. He took pride in getting someone else not to score a goal. And he was a fantastic trash talker: ''Come on, come on, let's have it... you think you can go past me? Oh yeah?''

Thierry Henry called you the best player he ever played with, but who would win in a one-on-one kickabout between you?

Marvin Rose, Reading

We never did that! Even in training sessions there's so much respect that you wouldn't go at each other. He would have beaten me for pace without a doubt. But in training, if he was one-on-one with me, he would pass to someone else and it was the same the other way around. With other players you want to make a statement. But going against him... no!

Why did you change your mind after saying you wouldn't go into coaching?

Paul Aminu, Glasgow

When I stopped playing I didn't want to go into coaching. I played golf and spent time with the kids for two years. My son was playing for a local team and I used to go with him to training. But every now and then I took a training session and I really enjoyed it. Back in Holland I could do my coaching badges in one year. At first I thought it's not for me, then I thought – just focus on it for one year. I got my diploma, so I can be a coach wherever I want to go now. Marco van Basten was straight on the phone. I had to get in certain hours with a professional team for the course. Marco said: "Why don't you do it with Ajax?" I can see myself coaching there one day. Maybe coach the strikers a few times a week. And I can see myself doing that at Arsenal – I could be part of that staff. Coaching brought me back into the game, but I needed a push.

Is traditional, clever, playful, beautiful Dutch football dying?

Joey Voce, Liverpool

Yes. I feel it's dying, but other teams are growing. If you look at the way Barcelona and Arsenal play, they could be Dutch teams. When one ball is given, numbers two, three, four and five are moving already. The Dutch teams aren't playing like that. If you look at the Dutch game you see one player with the ball and one other moving. No one else. So the one who is moving gets the ball. It becomes easy to defend. So there are few successful passes and not a lot of movement. It's more the long ball, and the foreign players who come in aren't at the same level as our youth players.

I hope that at Ajax at least we just give chances to the youth players. Maybe the first year they're not as good as other players, but just give them the experience and give them the confidence to play football. We have to do things differently. Years ago, when I joined the first team, with Cruyff, we played with two wingers – attractive, attacking football, and everyone in Europe was talking about us; us and Arsene Wenger's Monaco, who played the game in a similar way. Now it's gone. Now Barcelona and Arsenal are the two teams that play football differently from other teams.

Interview: David Winner. Portrait: Steve Orino. From the February 2011 issue of FourFourTwo.

Join The Club

Join The Club