When the FA Cup third round lasted 66 DAYS: 261 postponements, snow drifts... and flame-throwers

Paul Simpson relives the Arctic anarchy of 1962/63, when the winter weather played havoc with the football fixtures

It took 66 days to complete the third round of the FA Cup in 1962/63. The chaos, hardship and forlorn hopes that afflicted British football in the coldest winter since 1740 are captured in the stamp on the cover of Sheffield United’s third-round tie against Bolton Wanderers, due to take place on January 5 1963, which read: “After many postponements due to unprecedented winter conditions, match finally played 20th February 1963, kick-off 7.15pm (or so we thought until one hour beforehand!) AT LAST! 6th March 1963, kick-off 7.15pm.”

That heartfelt, triumphant 'AT LAST!' was very nearly the final word on the longest round in the cup’s history. The third round suffered 261 postponements (Lincoln City vs Coventry City was called off 15 times) as 15-foot snowdrifts, gale force winds, freezing fog, three months of frost, and temperatures sinking as low as -20.6C, made it nigh-on impossible to play football. A round that started on January 5 – when just three matches were played – finally staggered to a conclusion when Middlesbrough beat Blackburn Rovers 3-1 at Ayresome Park on March 11.

During this round, the FA became so alarmed by the freeze’s financial repercussions – Blackpool, for example, didn’t play a home game between December 15 and March 2 – it offered clubs interest-free loans. The clubs weren’t the only ones feeling the pinch.

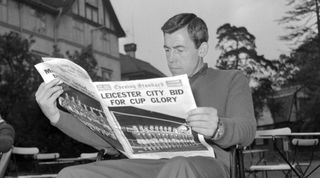

With no matches to inspire millions of punters to guesstimate score-draws, the bankruptcy-fearing pools companies created the Pools Panel, a thoroughly British institution that first met on January 26 1963 at London’s Connaught Rooms to invent the day’s football results (but not, bizarrely, the scores).

The first panel was chaired by Lord Brabazon, a peer who knew a lot about aircraft and golf. He was assisted by such retired players as Ted Drake, Tom Finney, Tommy Lawton and George Young, former referee – and future doyen of It’s A Knockout – Arthur Ellis and a Tory MP called Gerald Nabarro, better known for his handlebar moustache and private licence plate (NAB1) than sporting knowledge.

After the panel had forecast its first results (23 home wins, seven draws and eight away wins), an inebriated sportswriter shouted at Nabarro: “How the f*** could you say Port Vale would beat Northampton? You wouldn’t know a football if it hit you in the f***king face.” Unfazed, Nabarro said: “Sir, you are drunk, and even if you were sober you would get the same answer: ‘No comment’. And you can quote me on that.”

By the time the FA had contrived to create some semblance of order out of climactic chaos, the season had to be extended which meant that the FA Cup final would kick off, three weeks later than planned, on May 25 1963.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Only three out of 29 ties were played

The weather had started to turn in December. Freezing fog had forced 18 Football League matches to be called off – and eight abandoned on December 22 1962. Four days later, most of England was covered in 14 inches of snow. The snow kept falling, the frost never loosened its grip and the ice on the Thames became so thick that a car rally was held on it. January 1963 would go down as the coldest month of 20th century Britain.

Much of England was under a blanket of snow, the price of fresh food soared by 30 per cent, and in many areas the mains water supply froze. The English game wasn’t really ready for such a drastic, sudden crisis.

Some football clubs still didn’t have floodlights, so the FA urged clubs to play in the afternoon to avoid power cuts. Only a few grounds (Goodison Park among them) had undersoil heating. And the science of groundsmanship was still in its infancy.

So on January 5, only three FA Cup third-round ties actually took place: in the north-west, Preston lost 4-1 at home to Sunderland and Tranmere drew 2-2 with Chelsea. In the south-west, Plymouth were beaten 5-1 by West Brom.

The other 29 were postponed. With only Sunderland and West Brom definitely through to the fourth round, 62 clubs entered what The Times dryly described as “one of the most unusual draws in the history of the competition” at the FA’s Lancaster Gate headquarters, complaining: “There are so many alternatives that the whole business for the moment resembles a nest of Chinese boxes one inside the other.”

On the pitch, the highlight of what should have been a busy week of FA Cup third round action was probably Jimmy Armfield and Tony Walters skating over Blackpool’s ice-covered Bloomfield Road pitch for Daily Mirror photographers. The Times hoped such pitches might help a few Davids skate rings around the competition’s Goliaths. Mysteriously, it didn’t.

Realising the freeze wasn’t going to thaw anytime soon – and knowing how hard the lack of gate receipts would hurt their finances – desperate football club directors clubs felt obliged to consider any idea, no matter how ludicrous, to make their ground playable.

Danish snow-shifting tractors, flame-throwers, hot air machines and de-icing pellets were all tried. On January 22, Norwich made what a club spokesman called “a last desperate effort”, treating the pitch with flame-throwers which “served no purpose whatsoever for as fast as the ice melted, it froze again”.

Even when the snow was cleared, the ground was often frozen up to a depth of three feet. Wrexham smothered their Racecourse Ground with more than 80 tons of sand – and were rewarded by being able to play their tie only four days later than planned, losing 3-0 on a beach of a pitch to Bill Shankly’s Liverpool.

Oil drums and burning coke

If anything, this rupture of the season helped Leicester. In the summer of 1962, groundsman Bill Taylor had relaid the Filbert Street pitch, treating the topsoil with a blend of fertiliser and weed-killer that generated enough heat from the chemical reaction to mitigate the frosts.

As Gordon Banks recalls in his memoirs: “The groundsman augmented this affect by placing oil drums filled with burning coke at various points around the pitch, which raised the air temperature enough to ward off the severest frost. A nightwatchman sat up throughout Friday night to ensure all was safe. These braziers remained on the pitch until about 11am on a Saturday morning. An hour later, when the referee arrived to inspect the pitch it was playable and the game was given the go-ahead.”

So after beating Grimsby Town 3-1 only four days later than originally scheduled, Leicester were able to play their fourth-round tie, at home against Ipswich, at the end of January. While many clubs didn’t play a match for 10 weeks, the Foxes were back in action in five. Even before the third round had finished, Leicester had beaten Ipswich 3-1 to ensure their place in the last 16.

Under manager Matt Gillies, Leicester played a short passing game in which impish inside-left Davie Gibson and indefatigable left-winger Mike Stringfellow swapped positions and hit angled posses into the box for centre-forward Ken Keyworth, who had started out as a deep-lying midfielder, to run onto. Behind them, Frank McLintock often ran into the space vacated by his back-tracking inside-right Graham Cross.

All this short passing and interchanging divided pundits, some journalists hailing it as creative, others groaning that it was defensive. When City returned to action, they changed tack a little – hitting more longer balls to the wingers – and were so effective, winning nine games in a row in all competitions, that they were dubbed the “Ice Kings”.

Yet things, as Banks’s memoirs make clear, were hardly back to normal. “The pitch had partly frozen over again come three o'clock, especially the end under the shadow of the towering double-decker stand.” Knowing that half the pitch was still frozen, Banks took to the field in odd boots: on his right foot he had his normal leather-studded boot; on his left a boot with moulded rubber studs better suited to hard surfaces.

He would carry the other two odd boots under his arm and switch as soon as he knew which end City were defending in the first half. He also filed down his leather-studs because the exposed nail heads gripped the frozen ground better. (Luckily for Banks, officials had not yet started checking players’ studs.) Though he says: “I was always careful not to expose them in such a way that could cause injury”, such a ruse would be illegal today.

With no heating in his house, Banks ate more hot dinners to keep warm, gaining a few insulating pounds in the process. McLintock followed suit but recalled: “That was a rotten winter to live through. No matter how much coal we threw on the fire or gallons of hot steaming soup we shovelled down, we went weeks without being warm.”

As extreme as Banks’s filed-down studs sound, the footage of games played in such absurd conditions makes such precautions seem utterly reasonable.

The Pathé newsreel clip of the third-round tie between Tottenham and Burnley at a packed, snow-covered White Hart Lane on January 16 – which kicked off at 2.15pm, not 7pm, because the electricity board feared a power cut – begins with the announcer asking: “And the question for all the players is: can they cope with the skating rink surface and play something that’s not a mere travesty of football?”

The answer, inevitably, was no. Spurs had outclassed Burnley in the 1962 FA Cup Final and were dreaming of a third successive appearance at Wembley, but never found their rhythm and lost their tempers, with winger Terry Dyson kicking out in frustration and sparking a melee. The Clarets won 3-0 but the most enduring image of the match was their winger John Connelly going sprawling and, in the announcer’s words, “imitating an airplane belly landing”.

Mud, Malta and Manchester United

If you weren’t playing, life wasn’t much easier. Stoke's tie against Leeds was postponed 12 times. Captain Bobby Collins recalled that the squad still trained five days a week, playing on a frozen school pitch with an even surface. “You would work and build up to things all week, and then at the end of it all was another disappointment.” Don Revie’s Leeds side were still in the old Second Division and couldn’t afford to travel to keep in shape with a few friendlies. “For all the training,” Collins said, “the lads had so much energy inside them that they were praying for a game.”

The directors were praying too. Harry Reynolds, Manny Cussins and Albert Morris loaned Leeds more money and had to make personal guarantees to persuade the bank to raise the club’s overdraft. Maybe they should have taken their cue from Halifax Town, who turned The Shay into an ice rink and charged the public to use it.

All these prayers were finally answered on March 6 when, two months late, they faced Stoke at Elland Road. The pitch had been thawed by a hundred burning braziers, leaving the entire playing surface smothered in four inches of mud. Focusing on winning promotion to the First Division, Stoke didn’t risk the great, 48-year-old Stanley Matthews and lost 3-1 to a Leeds side that hadn’t won an FA Cup tie for 11 years.

A handful of clubs did go abroad. Keen to keep his promoting-chasing squad fit, Chelsea manager Tommy Docherty arranged a friendly against Malta. The Blues won but euphoria turned to frustration as the closure of British airports delayed their return.

Coventry, Manchester United and Wolves played it safer, staging friendlies in Ireland which was, mysteriously, much warmer than England. To reduce fixture congestion, the FA said clubs could play ties on available neutral grounds, prompting Sky Blues manager Jimmy Hill to suggest the club’s third-round match against Lincoln be played in Dublin. Maybe Lincoln should have agreed, because when the sides finally met, on March 6, the Imps lost 5-1 at Sincil Bank. Lincoln were obviously rusty: their centre-forward Brian Punter mistimed a pass just after kick off-and, within 15 seconds, City’s inside-forward Jimmy Whitehouse had scored.

Five days later, Middlesbrough beat Blackburn 3-1 at Ayresome Park. The third round might finally have been over but the chaos wasn’t. The fourth-round draw had been an unusually theoretical affair, in which every tie featured at least one either/or. The fifth-round draw was in danger of seeming even more absurd. With 48 teams still in contention for 16 places, the FA decided the best way to avoid such surrealism was to postpone the draw – which they did, for the third and final time, on February 9 1963.

By the time Alan Peacock, Brian Clough’s strike partner at Middlesbrough, scored the goals to take them through to the fourth round, eight sides had already reached the fifth: Chelsea, Everton, Leicester, Liverpool, Orient, Southampton and Sunderland (who had beaten non-league Gravesend & Northfleet, the only David left, 5-2 in a replay). Normal service wasn’t really resumed until the fifth round, with all eight ties taking place over nine days. The FA Cup was running late but at least every team was finally at the same stage of the competition.

After all the postponements, flame-throwers and gallons of soup, the semi-final line-ups were surprisingly unsurprising. Southampton lost 1-0 to Manchester United and Leicester overcame Liverpool primarily because the Foxes' keeper showed the form that was to earn him the nickname 'Banks of England'. The Reds had 30 shots – compared to City’s three – but still lost to a Stringfellow goal.

On May 25, Gillies’ Leicester kicked off the FA Cup final as slight favourites. A league and cup double had seemed on the cards until they lost four league games in a row before the final. Matt Busby’s Manchester United had laboured in the league since the thaw and finished just three points – and two places – clear of relegation. Yet the Ice Kings were not to reign on Wembley’s immaculate grass. United won 3-1 with goals from Denis Law and David Herd (2). Keyworth scored a late consolation for City.

For Gillies’ Leicester, this was as good as it got. Their chance of greatness had slipped away with the thawing ice. Gone, too, was British football’s curiosity about Gillies’ unorthodox tactics – though Shankly would tell Gordon Milne and Tommy Smith to swap positions in the manner of Cross and McLintock.

For the FA, the overriding sensation after the final was relief. Writing in the Essex FA’s official handbook that year, president Sir Stuart Mallinson depicted the season of the big freeze as the latest episode in a continuing narrative in which British stiff upper lip, native ingenuity and the spirit of the Blitz once again triumphed over adversity, noting how “with patience and good humour the clubs adapted themselves”.

For Busby, victory in 1963 was a giant step on the road back to greatness. The FA Cup was United’s first proper trophy since the Munich disaster. He must have felt, to echo the stamp on the cover of that Sheffield United programme: “At last!”

Next: 10 stars of the 1962/63 third round who went on to make a real name for themselves...

Before they were famous...

Ten stars of the 1962/63 third round who went on to make a real name for themselves...

Gordon West, 19, Everton

Kept a clean sheet for the Toffees in their 3-0 win over Barnsley. Won the FA Cup with Everton in 1966 but is best known for turning down a place in the England 1970 World Cup squad to stay with his family.

Paul Reaney, 18, Leeds United

Gave up being a mechanic to become a full-back and marked his FA Cup debut by scoring his side’s second in their 3-1 win over Stoke. Won the centenary FA Cup final in 1972 with Leeds.

John Sillett, 26, Coventry City

The Sky Blues full-back set up his side’s opener in a 5-1 thrashing of the Imps. Won the FA Cup as Coventry manager in 1987.

Frank McLintock, 23, Leicester City

Inspired half-back who didn’t have to be at his best as Leicester beat Grimsby. After losing two finals with the Foxes, he joined Arsenal, skippering them to the Double in 1971.

Ron Saunders, 30, Portsmouth

The Pompey striker’s two goals sank Scunthorpe. Won the league as Aston Villa boss, leaving the club a few months before they won the European Cup in 1982.

Terry Venables, 20, Chelsea

El Tel scored Chelsea’s third as they beat Tranmere 3-1 in a replay at Stamford Bridge. Left after a row about a curfew with Tommy Docherty in 1966 and won the 1967 FA Cup with Spurs – against Docherty’s Chelsea.

Johnny Giles, 22, Manchester United

Ruthless playmaker who scored in the Red Devils’ 5-0 win over Huddersfield and started the move that led to Herd’s first goal in the final. Frozen out of the team by Busby, he joined Leeds and won the FA Cup again in 1972.

Mike Summerbee, 20, Swindon Town

George Best’s favourite football fashionista was one of Swindon’s heroes in their run to the fourth round, where he looked lively against the mighty Everton. Won the FA Cup with Manchester City in 1969 – against the 1963 losing finalists Leicester.

Jimmy Melia, 25, Liverpool

Scheming midfielder who scored the third in the Reds’ 3-0 win over Wrexham. As manager, was famous for his lucky white shoes and steering Brighton to the 1983 FA Cup Final – which they lost to Manchester United.

Colin Grainger, 29, Port Vale

Scored from the spot as the Valiants beat Gillingham 4-2 to reach the fourth round. Though he won seven England caps in the 1950s, he is best known as “the singing winger”, quitting the game in 1966 to sign for HMV and share a stage with the likes of Shirley Bassey, Frank Sinatra and Engelbert Humperdinck.