Missing for 30 years: What happened to the Jules Rimet trophy?

Sam Rowe tells the story of the legendary trophy...

Not quite the World Cup curtain raiser, but a twitch of the net curtains at the very least. On Friday, as the usual gaggle of besuited ex-pros fish out numbered balls to determine who plays who next June in Brazil, all eyes will be on one thing - no, not the frightfully gorgeous model-types inexplicably brought in to preside over the draw, but a 14.5-inch tall chunk of 18-carat gold, otherwise known as the World Cup trophy.

But let’s face facts: it’s pretty boring. Sure, the trophy is highly coveted, with 32 nations duking it out every four years for the chance to grasp it aloft. It’s immensely valuable, too, believed to be worth around £7m in change.

And yet the 13.61-pound trophy, created in 1970 after Brazil kept the original following a trio of World Cup wins, will never accrue the same scandal, sex appeal or Hollywood-esque drama as its predecessor.

Hunted by the Nazis and stolen before the 1966 World Cup only to be retrieved by a black and white collie, the Jules Rimet trophy has been missing for 30 years this month (the exact anniversary is December 20), having been pilfered in Brazil, never to be seen again – supposedly melted into gold bars by its captors.

But this ultimately successful attempt to snatch the hallowed statuette - held as dear to football fans as the Holy Grail is to Christians… and perhaps Monty Python fans - was merely the last of many.

The story of the trophy

First awarded to Uruguay after they beat Argentina in the inaugural tournament final in 1930, the ‘Victory’ or ‘Coupe du Monde’ (World Cup) trophy was one-foot high, made with gold-plated sterling silver and created by French sculptor Abel Lafleur. In 1946 it was renamed after Jules Rimet, the FIFA president who passed the vote to establish the World Cup in 1929.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

After Uruguay’s maiden cup win, victory for Italy followed in 1934 and ’38, before the Second World War disrupted things somewhat. That’s not to say both the tournament and trophy weren’t sought after – Adolf Hitler famously applied for a 1942 tournament to be held in Germany, while FIFA vice-president Ottorino Barassi prevented Nazi officers from pinching the Jules Rimet by storing it in a shoebox beneath his bed, a place they failed to look when searching the Italian official’s property.

It was also the Germans – or West Germany, more specifically – that added a fresh layer of mystery to the curious case of Jules Rimet in the 1950s, as following West Germany’s victory in 1954, the statuette appeared for Sweden’s 1958 tournament fitted with a distinctively altered base, along with a few extra centimetres in height. Some believe this was in fact a replica, the original Rimet being either lost or stolen in Germany the year before.

Of course, by now we all know about the trophy – whether original or German imitation – going missing months before England’s victorious World Cup campaign of 1966; lifted from a stamp exhibition and discovered by Pickles the dog a week later (with ransom notes, demands for £15,000 and a bag stuffed with paper unfolding in between).

“Less well known is that after Pickles’ discovery, England’s Football Association secretly asked the jeweller George Bird to make a replica,” says sports writer Simon Kuper, who embarked on his own search for the mythical trophy. “Bird produced a gilded bronze trophy that looked just like the cup Pickles had found.

“Now there were two Rimets, or perhaps three if the original had indeed disappeared in the 1950s.” What’s even more intriguing, notes Kuper, is that after Bird’s death in 1995, his replica Rimet was sold at auction for a staggering £254,500. The ‘anonymous’ bidder? FIFA.

“In 2006 I asked FIFA if it had thought Bird’s trophy was the real Rimet. I didn’t expect a reply,” admits Kuper. “But FIFA’s media office emailed back [and said], ‘Yes, FIFA took the decision to buy this trophy as it was thought to be the original one.’”

Regardless of whether FIFA had managed to procure the original Jules Rimet trophy (spoiler alert: they didn’t, it was Bird’s bronze duplicate), the statue retrieved by Pickles the collie was retained by Brazil in 1970, as tournament rules then dictated any country to score a hat-trick of victories could have the cup for keeps. And keep it they did, for 13 years, until two thieves hog-tied a nightwatchman in the Rua da Alfandega building, breached the trophy’s bullet-proof glass casing and made off with the Rimet.

Without wanting to point fingers, Brazil may have been asking for it, even if only a little. Reminiscent of a commentator deriding a striker’s performance seconds before a 30-yard scissor-kicked goal, it was Brazil’s own snooty schadenfreude came back to haunt them.

Burgled in Brazil

“At the time of the theft of the trophy in England in 1966,” writes Martin Atherton in his book, The Theft of the Jules Rimet Trophy, “Abrain Tebel of the Brazilian Sports Confederation had stated that ‘It would never have happened in Brazil. Even Brazilian thieves love football and would never commit this sacrilege.’” But, fast-forward to the early hours of 20 December 1983, and that was precisely what transpired.

With a nation in mourning, the fallout from the robbery was quite savage. Though Brazilian idol Pele sympathised with the perpetrators, blaming the robbery instead on ‘desperation’ due to the country’s widespread poverty, in 1989 one of the rumoured suspects, Antonio Carlos Aranha, was found dead, having been shot seven times. It turned out not everyone was as compassionate as the former Santos striker.

Despite a countrywide manhunt (and trophy hunt) and a few arrests, no-one was ever charged with the robbery and, as such, it remains elusive. The most widely believed theory is that the Jules Rimet was melted and sold as bullion, but Kuper is not convinced.

“The story has holes,” Kuper claims. “For a start, the Rimet couldn’t be melted into gold bars because it wasn’t solid gold. Most likely, the German replica wasn’t all gold either. Moreover, the police had no evidence the trophy had been melted down. Indeed, the convicted Argentine gold dealer Juan Carlos Hernandez testified that he didn’t melt it down.”

Come mid-1984 and Brazil, in an attempt to restore national pride, had created their own replica, made from the moulds taken following West Germany’s 1954 win, and presented before a friendly match with England, which they lost 2-0.

This meant yet another replica was in existence, and yet the original Jules Rimet cup was still at large. Unless it was melted into gold that is, or lost in Germany way back in the 1950s. Obviously.

Back to today, and as the ritzy ball-picking soiree unfolds, spare a moment’s thought for poor World Cup 2.0, without even a name of its own. Sure, it’s worth millions (though experts would pour scorn on the suggestions it is solid gold, claiming it would be impossible to lift), but it will forever be a shadow of its predecessor.

A big hunk of unfulfilled potential and broken promises. Worth a fortune and somehow bitterly disappointing. Oh, and speaking of which, good luck to Roy Hodgson’s England in the draw.

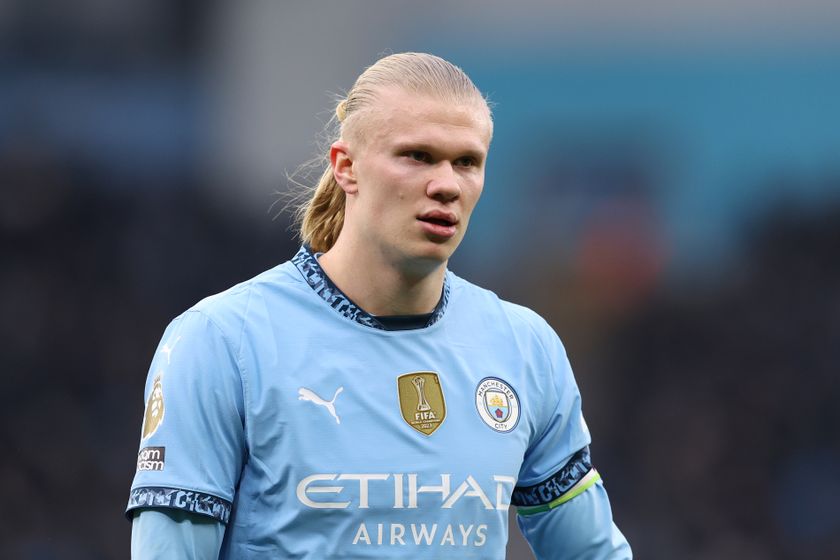

Is Erling Haaland injured this week? Premier League injury update

‘I remember the first time I was on Match of the Day, I had an absolute shocker. When I arrived home, I even got the piss taken out of me by my own family!’ Gary Lineker tells FourFourTwo about his unfortunate start to life on the flagship show