10 things you need to know about the Manchester clubs' humble beginnings

Forget here and now for a minute as Jon Spurling brings you tales of the pair's intriguing upbringings – including the dirty deeds that propelled United into a new era...

1) Naming difficulties

Two church wardens, anxious to stem the tide of unemployment, drunkenness and loutish behaviour of Gorton’s young men, formed St Marks (West Gorton) in 1880.

Initially it was part of a multi-sport endeavour, with rugby and football played on alternate weekends, as well as a cricket team in the summer.

A cluster of football clubs around the Gorton area existed at that time, with the St Mark’s side adopting the name Gorton AFC in 1884, following an unsuccessful merger with neighbouring side Belle Vue.

The club was hampered by an ongoing struggle to find and keep hold of suitable playing fields in its early years. In 1887, an unused piece of land on Hyde Road was discovered which offered the ideal setting for a football ground. As a result of this move the club changed its name once again and became known as Ardwick FC to reflect their new location.

2) "A pleasant game"

The ‘Gortonians’ had established themselves in the northern football scene, picking up victories in various cup competitions against local rivals. Newton Heath, who became Manchester United, faced the Gorton side numerous times throughout the 1880s and 1890s.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Newton Heath dominated the early period of this rivalry recording a 3-0 victory in the first-ever Manchester derby in 1881, and was described by the Ashton Reporter as "a pleasant game".

At this time, the clubs were just two of many fledgling sides in the Manchester area, and the fixture had no special significance. Both clubs grew in stature as the 1880s progressed.

The pair became the dominant teams in the Manchester area; the winner of the Manchester Cup was either Newton Heath or Ardwick every year between 1888 and 1893. Newton Heath joined the First Division, and Ardwick the new Second Division in 1892.

This local pecking order had already been highlighted in 1886, when Newton Heath hammered Gorton 11-1, which led to “much drinking and carousing among Heath followers,” noted Athletic News.

3) Toxic atmosphere

Manchester United’s ancestors were formed in 1878 as Newton Heath LYR Football Club. Secretary A. H. Albut procured the use of the Bank Street ground in June 1893 and it was at this juncture that the club’s fame grew.

The condition of the Bank Street pitch was, at least, an improvement on that of first ground North Road (described by United scribe Richard Kurt as “an assault course-cum-minefield”).

But Bank Street was notorious for the proximity of a chemical works. In the 1894/95 season, Walsall Town Swifts turned up at the ground and were greeted by what they regarded as a "toxic waste dump".

After lodging an official complaint about the environs to the referee, they took to the field only to be beaten 14–0. However, the Football League ruled in favour of Walsall and the match was ordered to be replayed. The Swifts only lost 9-0.

4) Meet the early-day poster boys

Relegated at the end of the 1892/93 season, Newton Heath may well have fallen into the abyss if it hadn’t been for the legendary financial juggling of Club Secretary A.H. Albut.

One of his more visionary ideas was to propose the Newton Heath Social Club, where players and fans could mix on equal terms over a pint and a game of snooker.

Albut – equally adept at dealing with both the press and accountants, knew that in order to keep his club’s heads above the financial parapet, the team needed to have a fair share of small-town heroes on the books.

Arguably the most high profile was the popular Belfast-born Jack Peden, the first Irishman to play in the Football League, or perhaps goalkeeper-hating Bob Donaldson, a tough Scottish striker of whom one team-mate commented: “When Bob goes up in the box, everything else has to go down.”

5) A dodgy scribe

Following Newton Heath’s 4-1 clobbering of West Brom in October 1893, the match report by the Birmingham Gazette’s William Jephcott so enraged Albut that he took the newspaper to court. Jephcott accused the “heathens” of using “dirty tricks” and “simple brutality”.

Several of the Heath’s leading lights took to the witness box, with Jack Peden claiming he kicked the Albion keeper in the stomach only because “I mistook his stomach for the ball because I was temporarily blinded by the sun.” After much deliberation, the judge ruled in favour of Newton Heath, but awarded them “the smallest coin of the realm”. Outraged by receiving just one farthing, (Albut had banked on receiving “a few hundred pounds”), the club continued to flirt with bankruptcy for the rest of the 1890s.

6) Being more like Bury

By the early 20th century, success on Manchester’s football fields lagged well behind that of rivals in Liverpool, Birmingham and Sheffield. The region’s most successful team had been Bury, twice winners of the FA Cup by 1903, and a younger club than either of its big city rivals.

After Ardwick’s financial collapse in 1894, club members proposed “a football club for Manchester” and Manchester City were accepted into the Second Division that summer, and promoted to Division One in 1899.

Newton Heath were relaunched as Manchester United in 1902. As Gary James and Dave Day point out in their article in Soccer and Society, it was “FA Cup success, football infrastructure and the establishment of Manchester’s football identity.” Both clubs promoted themselves to all sections of society, and their names – ‘City’ and ‘United’ emphasised what they hoped to represent to Manchester’s inhabitants.

7) City's first success

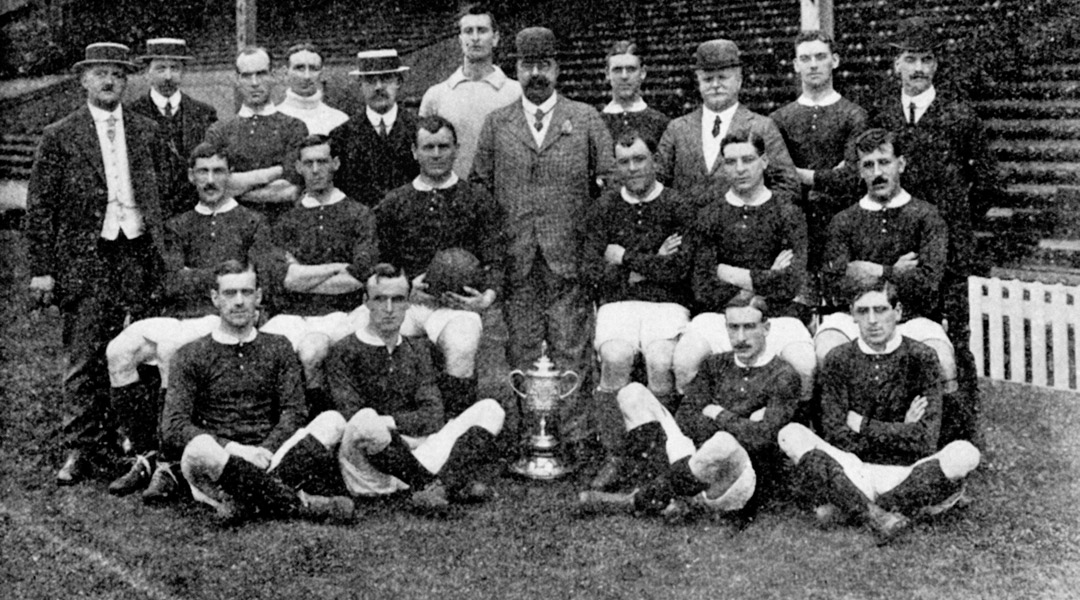

Manchester City made the breakthrough in the 1903/04 season, finishing runners-up in the Football League and winning the FA Cup after gunning down Sunderland, Middlesbrough, Sheffield Wednesday and Bolton.

Over 60 railway 'specials' took around 40,000 travellers from Lancashire to the final at Crystal Palace. The only goal of the game was scored by City’s Welsh skipper Billy Meredith. At the very moment Meredith scored, the hot air balloon deployed by Athletic News to gain unrivalled coverage of the match crash landed.

Initially, civic leaders and the police were reluctant to arrange for a civic reception to take place, but altered their plans as huge crowds gathered in force to welcome back the “team of the season”. Local newspapers left local rivalry out of proceedings, and portrayed City’s victory as “Manchester’s success”.

8) Meredith's match-fixing

Level on points with Newcastle United in the league in May 1905 and needing to beat Aston Villa on the final day of the season to seal the First Division championship, Manchester City froze on their big day and Villa won the game 3-2 at Villa Park. City finished third. Newcastle were crowned champions.

After the game Villa skipper Alec Leake claimed that City’s Billy Meredith had offered him £10 to throw the game. Meredith was found guilty of this offence by the Football Association, fined and suspended from playing football for a year. He was suitably brusque and up front about the whole affair, and City’s track record in financial chicanery.

City refused to provide financial help for Meredith and he went public, stating: "What was the secret of the success of the Manchester City team? In my opinion, the fact that the club put aside the rule that no player should receive more than four pounds a week... the team delivered the goods, the club paid for the goods delivered and both sides were satisfied.”

9) The fire sale that shaped a rivalry

As a result of this, the Football Association carried out a thorough investigation into the financial activities at City and concluded that they had been making additional payments to all their players.

Manager Tom Maley was suspended from football for life and City were fined £250. Seventeen players were fined and suspended until January 1907.

City were forced into an unprecedented fire sale, and placed all their prize bulls up for auction at the Queens Hotel in Manchester. United manager Ernest Mangnall signed the hugely controversial Meredith – who’d used virtually every newspaper column, article and interview he’d been connected with to argue the case for player power – for just £500.

Mangnall also purchased three other talented members of the City side: Herbert Burgess, Sandy Turnbull and Jimmy Bannister. Supporters of both clubs, as well as local dignitaries and officials, were keen that the players should remain in the city.

The Queens Hotel auction altered irrevocably the fortunes of both sides for the rest of the century. Without such an event, argues United scribe Richard Kurt, “We could easily have become a small-time satellite forever orbiting around the sun of Manchester City.”

10) Sorry, we can't be friends

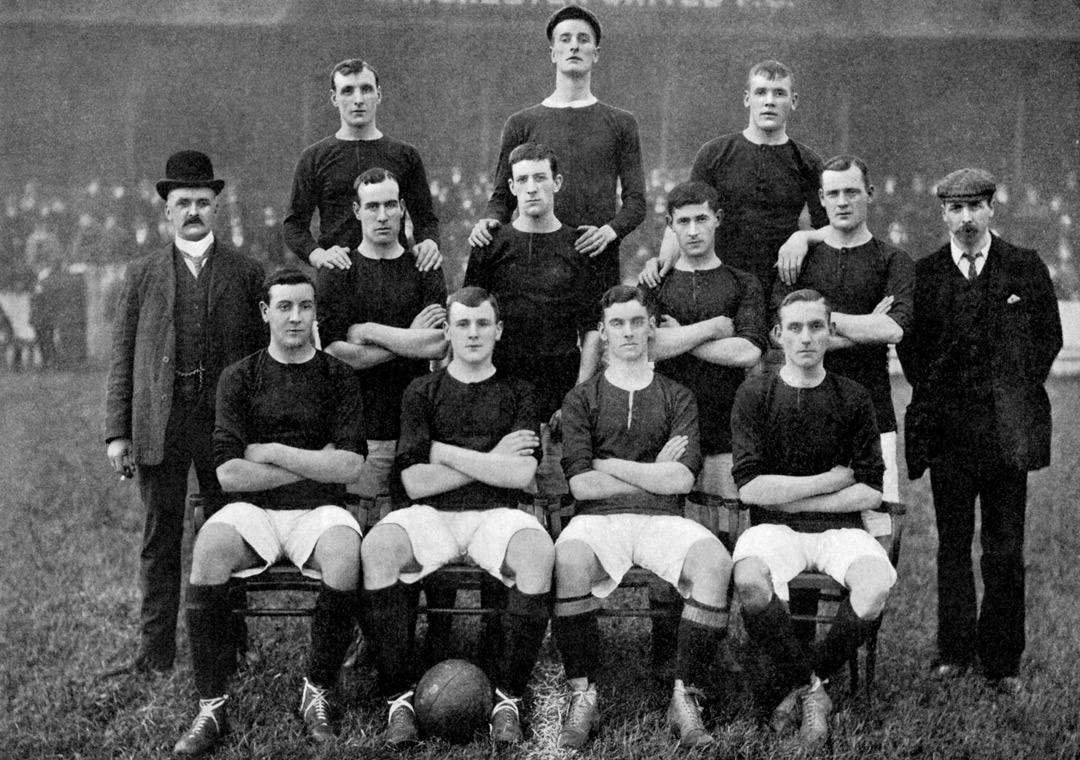

Instead, the former City players became the core of the United side that won the Football League in the 1907/08 season and the 1909 FA Cup Final. A tight-knit group, the former City players, along with United skipper Charlie Roberts plus activists at other clubs, formed the new Players’ Union in December 1907, with the twin aims of ending wage restraint and introducing freedom of contract for footballers.

The FA soon clamped down on the scheme. To show how close the two Manchester clubs remained, United requested that City director Albert Alexander led the 1909 homecoming after the FA Cup win.

A City official claimed: “This is a great moment for the town, even though United can be considered rivals.” It wasn’t a vintage year for City, though. As United basked in the limelight, they plummeted into Division Two.

Jon Spurling is a history and politics teacher in his day job, but has written articles and interviewed footballers for numerous publications at home and abroad over the last 25 years. He is a long-time contributor to FourFourTwo and has authored seven books, including the best-selling Highbury: The Story of Arsenal in N5, and Get It On: How The '70s Rocked Football was published in March 2022.