1971 Cup Winners' Cup Final: How Chelsea geared up for their first European triumph

Cocktails and high jinks were hardly textbook prep for Chelsea’s 1971 Cup Winners’ Cup Final against Real Madrid – but their sozzled stars made sure the party didn’t stop. Sadly, the headache would strike with a vengeance...

This story about Chelsea's victory in the 1971 Cup Winners' Cup first appeared in the May 2021 edition of FourFourTwo

Thursday, May 20, 1971. It’s 11am at the Hilton Athens Hotel, but 27-degree heat is already searing down on the poolside concrete. Among scorched football fans and bikini-clad holidaymakers, a group of Chelsea players ruminate over the UEFA Cup Winners’ Cup final a day before. The Blues had been moments away from beating the mighty Real Madrid to secure the trophy, when sweeper Ignacio Zoco levelled with the last kick of normal time. A replay was scheduled for Friday.

“All the lads were gutted we hadn’t won the first match, so some of the players went out,” Chelsea captain and legendary hardman Ron ‘Chopper’ Harris tells FourFourTwo. “Some came back on time… some came back later.”

With the second showdown mere hours away, the late Peter Osgood – the talisman now immortalised outside Stamford Bridge in statue form – decided to take the edge off with Scottish winger Charlie Cooke and cult hero forward Tommy Baldwin.

“We were only having a few beers – they always say before the match you shouldn’t be drinking,” Baldwin tells FFT, beginning to chuckle. “That wasn’t really drinking, it was like having a mouthwash!”

Osgood wrote in his 2003 autobiography of demolishing a “conveyor belt of cocktails” in the sunshine that day, remembering it as “one of the few times I saw Alan Hudson refuse a drink”. No saint himself, mercurial midfielder Hudson had found his team-mates living it up and wasn’t impressed, reminding them of one of the biggest matches of their careers the following day. Osgood told him, “You go home, you have to do my running tomorrow. Don’t worry, young Huddy. I’ll win us the game.”

“It was unplanned, one of those things that creep up on you,” Cooke recalled in his own memoir. “A couple of snifters and the hours can flash by, and it didn’t occur to us at the time that we were being irresponsible. Fans were dropping by now and then and having some banter, and it was a terrific, relaxed afternoon. We never intended it to be what it turned out to be.”

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

With the team having been strategically booked into the Apergi Hotel in Kifissia, 11 miles outside the lively city centre, the trio had broken manager Dave Sexton’s strict rule of being back in time for dinner at 7pm. Baldwin – a substitute for the first match – remembers being caught sneaking into the lobby by his boss.

“He fined three of us. I went, ‘All right, fair enough’ and turned away to go to my room,” he continues. “‘By the way’, Sexton told me, ‘you’re starting tomorrow!’”

This was Chelsea back in 1971, though – as famous for their antics on the King’s Road as they were for any feats on the pitch...

It was the second campaign in a row where Chelsea had made it all the way to a major final. The 1970 FA Cup showpiece captured Britain’s imagination: North vs South, brawn vs beauty, Don Revie’s uncompromising Leeds against Dave Sexton’s west London wideboys.

The truth about the two teams is blurrier than the stereotype. Leeds boasted players of superb technical ability – Billy Bremner, Peter Lorimer, Norman Hunter – while any player on the end of a challenge from Harris, David Webb or even Osgood wouldn’t forget about it in a hurry.

The dies were cast, however, and the final – which again went to a replay after a 2-2 draw at Wembley – became a bloodthirsty battle between bitter rivals. Premier League referee Michael Oliver re-watched the second game at Old Trafford, half a century on, and said he would have issued 11 red cards (they wouldn’t be introduced to English football for another six years).

The 1970 replay was eventually decided by a bundled Webb header in extra time and still stands as the fifth most-seen television broadcast in UK history, as a mammoth 28.5 million people tuned in.

With eyes averted their way, though, the Blues characteristically failed to trouble the 1970-71 league title race, and their defence of the FA Cup ended in the fourth round at home to Manchester City.

But Europe was a different story. Having first dispatched Greek side Aris Thessaloniki – a “bunch of dirtbags” according to Osgood – then eased out CSKA Sofia with a pair of 1-0 wins, Sexton’s men overcame a 2-0 deficit against Club Brugge in the quarter-finals. They ran out 4-0 victors after extra time at Stamford Bridge, in what Baldwin says was “the best game I’ve ever been involved in”. FA Cup foes (and Cup Winners’ Cup holders) Manchester City awaited in the semi-finals, with two injury-ravaged teams playing out a pair of dour matches. But it mattered not: Chelsea won each by a solitary goal.

When it came to the final, Real Madrid were a pale imitation of the team that had won the first five European Cups from 1956. They could have come up against Chelsea in the competition’s inaugural year, in fact, were it not for the shameful xenophobia of Football League secretary Alan ‘the Dictator’ Hardaker, who blocked the 1954-55 English champions’ invitation. Worse, he told Times journalist Brian Glanville that his issue with European football was “too many wogs and Dagoes”. Manchester United ignored his ruling the following year.

Real’s period of European Cup domination may have installed a philosophy that still pulsates through the club today, but back then Los Blancos had lost their shine. One member of the 1956-winning side – and the subsequent five successes – was amazingly in the line-up to face Chelsea some 15 years later. Paco Gento, now 87 and honorary president of the club, was a lightning-quick left-winger and Alfredo Di Stefano’s ultimate foil. “That was the best thing I’d ever seen,” gushed England icon Bobby Charlton.

He was in 1956, anyway. By 1971, Gento was 37 years old, decidedly less rapid and reportedly smoking 70 cigarettes a day. The rest of Madrid’s XI comprised the fag-end of their celebrated ‘Ye-ye’ generation – the all-Spanish side named after The Beatles’ She Loves You refrain, with the club’s rule of La Liga in the 1960s mirroring the Fab Four’s prominence during that decade.

Amancio Amaro, Pirri, Manuel Velazquez, Ramon Grosso and Zoco remained Madrid mainstays by the time Chelsea met them in the Greek capital, but much like their musical Merseyside counterparts, the magic was over by the early ’70s.

Real continued to be led by the great Miguel Munoz, but the 1969-70 season had ended with their worst league placing for 19 years (6th), and they had qualified for Europe only by winning the Copa del Rey.

Despite making the final, Munoz’s outfit had hardly lived up to their reputation in the lesser continental competition either. After navigating past Maltese minnows Hibernians and Austrian club Wacker Innsbruck, they faced a quarter-final which is remembered fondly in one corner of Britain. Cardiff were serial Cup Winners’ Cup entrants thanks to their monopoly of the Welsh Cup, and pulled off a historic Ninian Park triumph when the Second Division Bluebirds stunned Real 1-0 in the first leg. Two goals at the Bernabeu ultimately spared the Spanish giants’ blushes, before Pirri’s 82nd-minute effort meant they squeezed past PSV in the semis. It definitely hadn’t been pretty, but Real Madrid were on their way to Athens.

They were on their way a lot sooner than Chelsea, arriving the weekend before the final so that Munoz could fine-tune his wayward charges in four training sessions. What about the west Londoners’ meticulous preparation? “We never really thought about other teams,” shrugs Baldwin. “We simply worried about ourselves. We’d work the rest out on the day.”

“I was 25 in 1971,” Chelsea fan John Sestak tells FFT. “Two mates and I decided we had to go to Athens. The club were running an offer where you would fly across to Greece, stay one night and fly back the next day. It was £35 to fly out from Luton by jet. I had a row with them because I wanted to go by propeller plane, which was a tenner cheaper. In the end, I relented.”

More than 4,000 fans joined John on his journey, when the phenomenon of heading abroad to watch football was in its infancy. “The Greeks had seen nothing like it,” says Match of the Day statistician and Chelsea programme editor Albert Sewell. “The Shed took over Omonia Square and decoratively, incongruously demonstrated their arrival in the world’s oldest city of culture.”

‘Chelsea’s vast armada’, as Sewell labelled them, outnumbered their Real counterparts by more than two to one, but the Blues were also backed by much of the 45,000-strong Greek crowd inside the Karaiskakis Stadium, 200 yards from the sea on the Piraeus coast. This was ostensibly on the promise that the Londoners would return the favour later that month, when Panathinaikos took on Ajax in the European Cup final at Wembley.

But there was a more symbolic reason that the locals took to Harris, Hudson & Co. Greece had lived under a hated and violent far-right military junta since 1967; civil liberties were severely suppressed as the world’s oldest democracy was dismantled, with the junta prone to torturing any dissenters – or worse. While the Greek authorities were keen to put on a sheen of libertarianism for UEFA and their big final, the regime’s ideology aligned closely with that of General Franco, who was ruling Spain at the time.

Real Madrid, rightly or wrongly, were firmly seen as Franco’s team, and the ground’s VIP areas – as recalled by Osgood’s agent Greg Tesser – “were full of self-confessed fascists”. The players emerged onto the pitch flanked by guards, before being paraded around the surrounding athletics track in an ostentatious ceremonial march that delayed the kick-off by five minutes.

The clash soon reminded Chelsea that while Real Madrid were not the power of old, they were still Real Madrid. The Ye-yes battered the Blues, even in the face of a tremendous left-footed hooked strike from Osgood which put the latter 1-0 up shortly after half-time. Only a series of saves from Peter Bonetti and resolute defending saved them. “We were a bit fortunate – the first game was a bit iffy,” Harris admits to FFT.

All of the pressure told eventually, and Zoco pounced on a miskick from John Dempsey to equalise. “I’d only just come on and they scored!” laughs Baldwin. “They had a table with the medals laid out near the touchline, which they immediately packed up and took away.” The military guard ready to greet the champions retreated, and with neither team finding a way through in a tense 30 minutes of extra time, a replay was booked in for two days later at the same venue.

“Imagine that,” laughs Harris. “We were in a major European final, and then made to do it all over again a couple of days later. Now, teams say they’re tired playing a couple of matches a week!”

While Chelsea’s players came to terms with a second game against the Spaniards, their travelling support – clearly audible on the video footage of the match – had even bigger problems. With many Blues fans booked on flights departing Athens the following day, were they really willing to head all that way and not get to watch the deciding match? To the chagrin of the British embassy, a large portion of them decided the answer to that was a definite ‘no’.

Fans slept on beaches, in hotel lobbies and in bars as travel agents hurriedly attempted to organise rearranged trips back to Blighty. Some supporters got even luckier.

“There were so many Chelsea fans who’d stayed behind, they came to our hotel with nowhere to stay,” reveals Harris. “Everywhere was so expensive. I was rooming with Marvin Hinton at the time, and we ended up letting a few lads sleep on the floor. We weren’t the only ones who did that – we had a fantastic following for the game and appreciated that everyone stayed in Greece.”

Presumably unaware of his players’ surprise room-mates, boss Sexton had other things on his mind. He allowed his team the Thursday off – something he would later regret given the Hilton trio’s plans – and contemplated how his injury-ravaged side were going to cope with a second encounter against Real in three days. Osgood and Dempsey were doubts, while midfield dynamo John Hollins was out. Nursing a knee problem, he settled for watching the replay sat next to Kenneth Wolstenhome as the BBC’s co-commentator.

The first match had not been televised in the UK, meaning those who stayed behind had to listen to coverage on the radio. A letter in a Chelsea programme the following season tells of a group of supporters who travelled not to Athens but Belgium, where the game was being broadcast live.

Baldwin – even if he wasn’t yet aware – was to come in for Hollins, allowing Cooke to drop slightly deeper and have more impact on the game. It proved a masterstroke: Cooke woke up on the morning of the replay “with the sort of hangover I would have paid silly money to relieve” – not that it appeared to dampen his eventual performance.

Daily Mail scribe Jeff Powell was in Athens as a young reporter. “The crux came down to Amancio and Cooke,” he tells FFT. “Amancio was a wonderful footballer and tore Chelsea apart in the first match – they dominated that game and should have won. Come the second match, Charlie got himself going and overran Madrid.”

Amancio agreed, as he told Spanish press after the first showdown. “If we stop Charlie Cooke, we will win the cup.” His side were in the wars as well, though: Pirri, who had led Chelsea a merry dance in Wednesday’s tie, had broken a wrist and struggled through the replay in a bandage. The 48-hour turnaround proved too much for elder statesman Gento, who retired to the bench.

The Karaiskakis Stadium was nowhere near capacity for the replay. Madrid’s supporters – and a portion of Chelsea’s – had gone home, while local enthusiasm had seemingly been expended. The 20,000 who did turn up were treated to a different game.

The Blues had been hailed as a defensive ‘trojan horse’ in the first clash, but took the initiative with an attacking display inspired by Cooke. Two men shrugged off injuries to play vital roles. Stopper Dempsey, who had made such a fatal mistake two days earlier, gave Chelsea the lead with a stonking volley – “goal of the decade,” says Baldwin – while Osgood’s driven shot from outside the area six minutes later put them 2-0 up before the break. A second-half strike from Paraguayan winger Sebastian Fleitas wasn’t enough for Munoz’s Madrid, making for a first trophyless season since 1952-53.

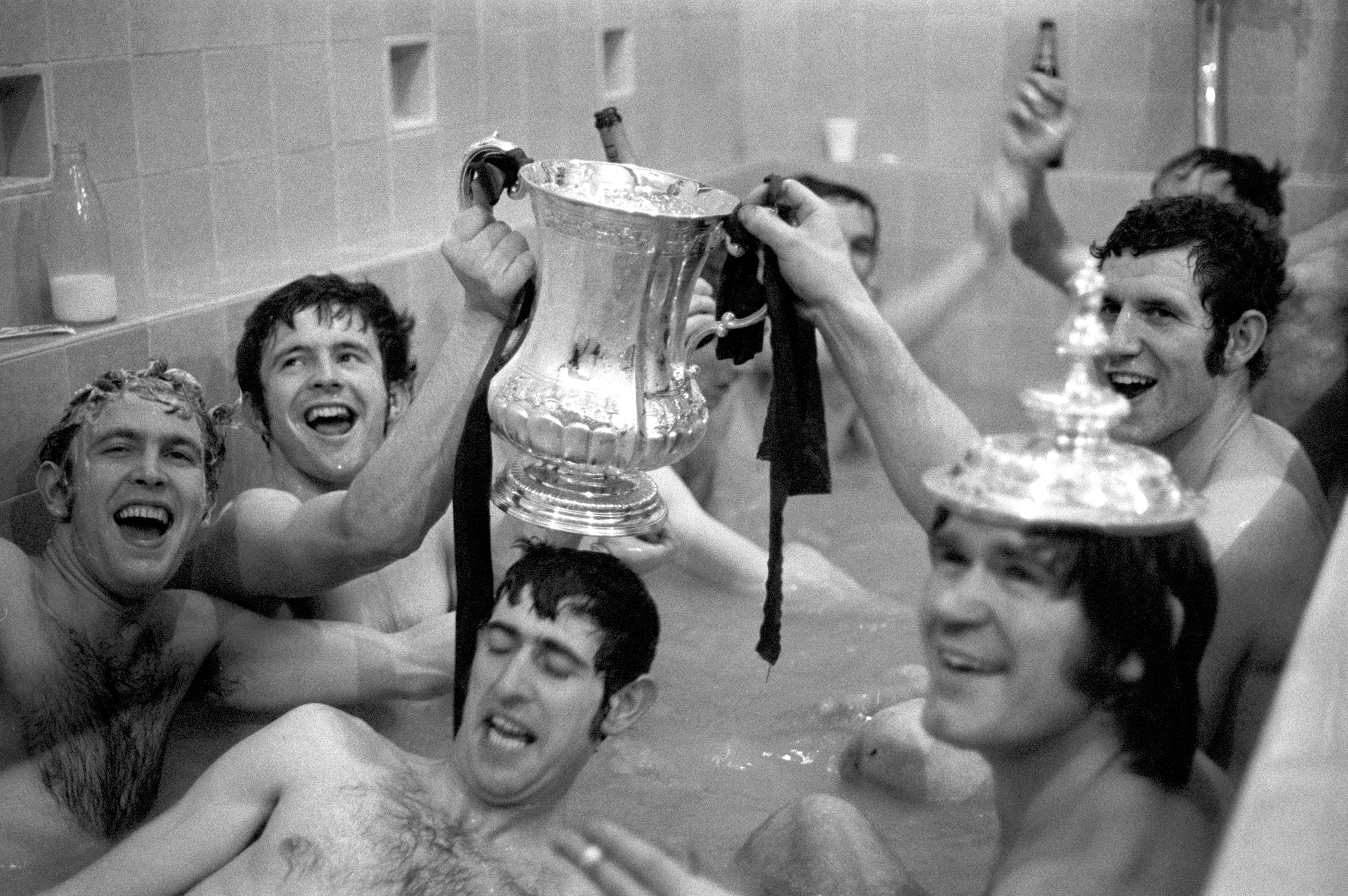

Osgood & Co, sporting their swapped white Real jerseys, embarked on a triumphant lap of the athletics track, joined by hundreds of presumably weary flag-bearing fans. Hardly encumbered with restraint before the match, the players were finally let loose.

“Charlie Cooke and I found this nightclub, and a couple of the press came along too,” Baldwin tells FFT. “We were smashing plates in the fireplace, like the Greeks do, and went to go home. This reporter came out and said, ‘Tom, Charlie – they want me to pay for all of that!’ He said, ‘I haven’t got any money’ – but neither had we, so we left him there with a big bouncer. I’m sure he was all right...”

With the King’s Road full of revellers – one World’s End pub informed The Mirror they had sold 1,000 pints that night – the bleary-eyed players were greeted by a huge welcoming party as they drove from Heathrow Airport to Stamford Bridge.

“It wasn’t like nowadays, when it seems as if Chelsea win a cup every five minutes,” says fan Sestak. “Winning those two trophies was like the World Cup in 1966, with street parties on the Fulham Road. This was the second big triumph – we were expecting it to go on for another 10 years.”

But four years later, the Blues were in the Second Division. Their rapid decline included the bitter departures of Osgood and Hudson, and stopping work only one stand into a full redevelopment of Stamford Bridge – a plan grandly named ‘the Stadium of the Future’. The East Stand, still there today, threatened to bankrupt Chelsea and hung like a millstone as the backdrop to two decades of yo-yoing between the top two tiers.

With the 1971 vintage demigods among fans of a certain age – and younger fans too – why did they not go one better and win the First Divison? The answer is possibly found in the bottom of a glass at the Athens Hilton.

“There was a King’s Road element about the boys,” explains journalist Powell. “They were a boisterous lot, which probably held them back. They were extremely talented – when the inspiration took them. Sexton was an intelligent coach, and when he could get hold of them they were formidable, but they were a swashbuckling, cavalier team and could have hot days and not-so-hot days.”

Captain Harris agrees. “If you went away somewhere and performed in front of only 25,000 and it wasn’t against a big club, the enthusiasm just didn’t seem to be there,” he admits. “The atmosphere wasn’t the same. We had three exceptional players in the side – Cooke, Osgood and Huddy. They pulled all the strings and the bigger the occasion, the better these lads performed.”

It took Chelsea until the late 1990s to taste success again, when stars such as Roberto Di Matteo and Gianfranco Zola matched the heroes of Athens by winning the FA Cup and Cup Winners’ Cup in consecutive seasons. The glamour of the King’s Road was back – they even beat Real Madrid in the 1998 Super Cup.

But did they do it on a hangover?

Subscribe to FourFourTwo today and get your first five issues for just £5 for a limited time only - all the features, exclusive interviews, long reads and quizzes - for a cheaper price!

NOW READ

EURO 2020 England stars show off retro Italia 90 Mash-Up shirt

CORINTHIAN FIGURES How the big-headed football collectibles took the world by storm

COVID-19 New lockdown guidance: What games will football fans be able to go to under new rules?