1974: What change at the top meant for England's elite

What happened last time top three changed bosses

Just imagine if Sky Sports News had existed in the despicably, delightfully dirty decade they call the 1970s.

We’re picturing a brown corduroy ticker, the Soccer Saturday gang smoking tabs, and an appallingly sexist segment in which Georgie Thompson reads out betting tips under a disco glitterball. If they had, then the ever-eager channel may have combusted from over-excitement in the month of July 1974.

The spring of 2013 has been compelling, with Manchester United, Manchester City and Chelsea all finding new headmasters to oversee the next footballing term. But if the last time England’s top three clubs did such a thing is anything to go by, the results could be extraordinary. Rewind 39 years and the status quo evident at England’s champions, Leeds United, runners-up Liverpool and third place Derby County, was shattered beyond recognition.

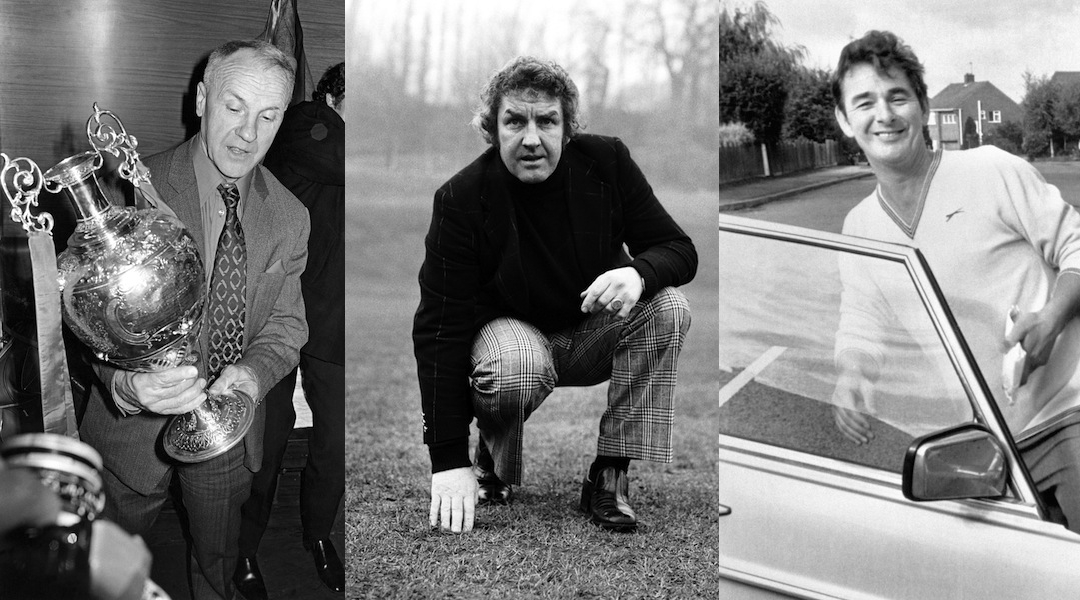

On July 4, 1974, Don Revie accepted the FA’s offer to manage England, ending 13 glorious years in the Elland Road hotseat. Eight days later, Bill Shankly gob-smacked football in general and Liverpudlians in particular by announcing his retirement after 15 years reconfiguring the Reds from zeroes into heroes.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

And a fortnight after that, Brian Clough – who’d started the season as the don of Derby, a club he’d transformed beyond recognition in six years, before enjoying a brief sojourn at Brighton & Hove Albion – took over at Leeds, a team he famously didn’t like very much. As all this was going on, the Rams were quietly adjusting to a new regime headed by Dave Mackay.

While Revie’s wish to have a crack at the England job was understandable, Shankly and Clough’s decisions were met with incredulity. In a Twitterless age, news spread slowly, and somehow seemed more monumental: witness the late, great Tony Wilson – an unabashed Manchester United fan – roaming Merseyside streets for local news programme Granada Tonight, gleefully informing Scousers that their messiah had packed it in.

One mullet-toting lad is so distraught it’s almost as if the soon-to-be Factory Records kingpin has informed him that his mum and dad have just driven their Ford Capri off the Albert Dock and won’t be home for tea.

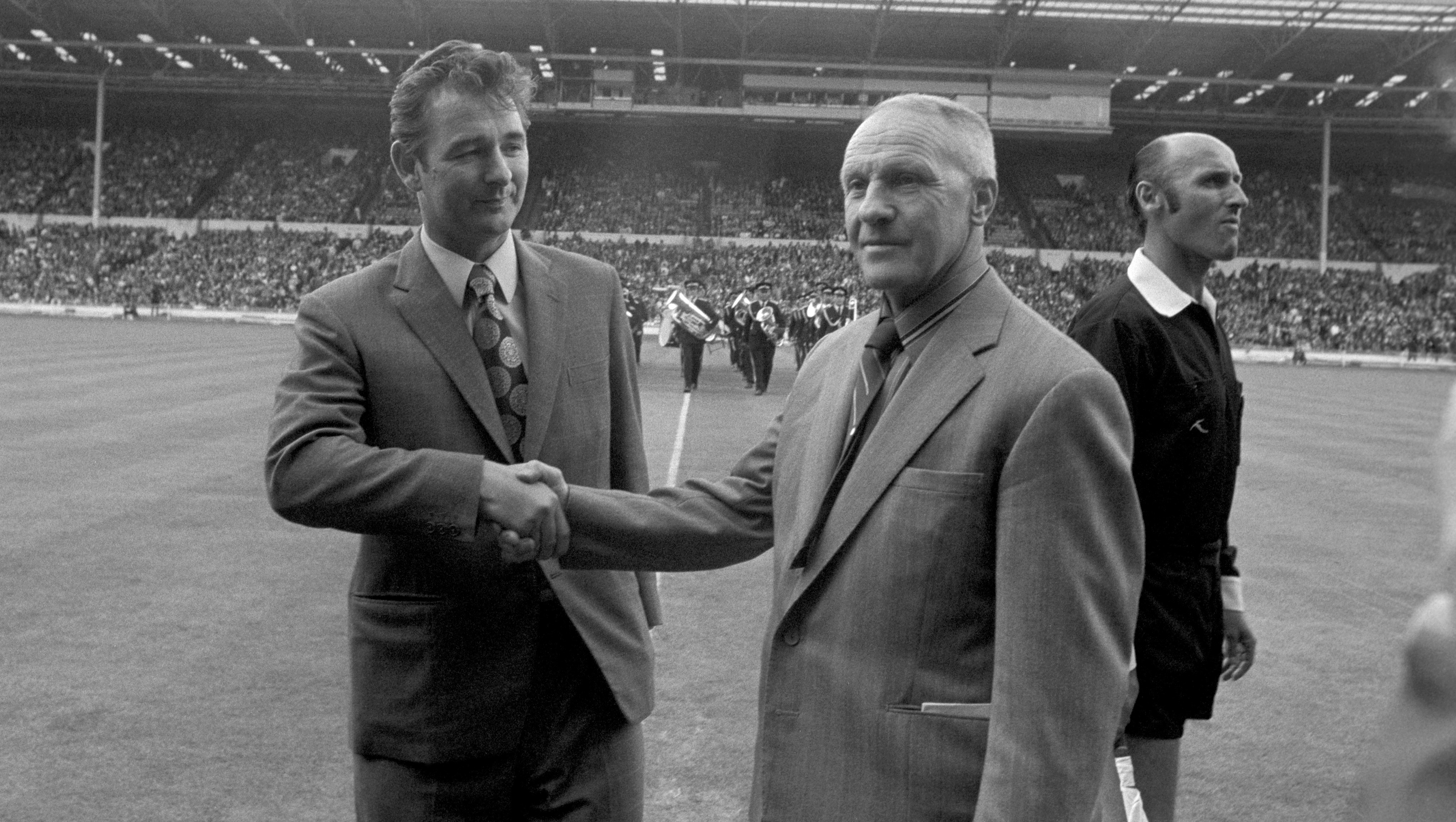

The image of Shankly and Clough leading out Liverpool and Leeds for the 1974 Charity Shield match is pricelessly distressing: arguably the two most quotable men in football history, gloriously dapper, quietly stewing on the worst decisions they’ve made in their entire life.

Anyone who has read David Peace’s The Damned United will be aware of how Clough’s 44 hellish days at Leeds panned out. Riddled with inaccuracies though it may be (and Peace always maintained it was a fiction), the central narrative remains undeniable: he hated them, and they hated him. By October, Jimmy Armfield had taken his place.

Clough bounced back and went supernova at Forest. Leeds never did. They finished 9th in 1974-75, Revie’s dream team disintegrated, and despite a European Cup final that season, gradually faded as a force. Revie’s record of two titles, an FA Cup, a League Cup and two Fairs Cups (plus 11 runners-up spots in major competitions) towered over his Elland Road successors for decades: only their 1992 top-flight title win rivalled anything their greatest gaffer did.

The salad days were over for Revie, too. His tenure as England boss was moribund; struggling to adapt to his methods, the Three Lions failed to reach Euro '76 and were missing out on Argentina '78 when he controversially jumped ship to coach the United Aarab Emirates. The incensed FA banned him for 10 years – he never returned to British management, coaching only Al-Nasr and Al-Ahly. Apparently they bore a longstanding grudge, sending nobody to his funeral in 1989 or granting a minute’s silence across England’s grounds.

Shankly’s withdrawal into the shadows was even more harrowing. Just 58, he soon regretted a decision he said was like “going to the electric chair”. Bored by civvy life, by August he was back attending training at Melwood but the Liverpool executives, worried his aura might affect Bob Paisley, asked him to desist.

The Scot began to advise other teams – including Everton, a side he’d once said he would close the curtains on if they were playing in his back garden – and became bitter about his treatment from an institution he’d led to three league titles, an FA Cup and a UEFA Cup. Seven years later he was dead at the age of 68. Co-incidentally, David Peace’s new book, Red Or Dead, is a meditation on Shankly’s disintegration.

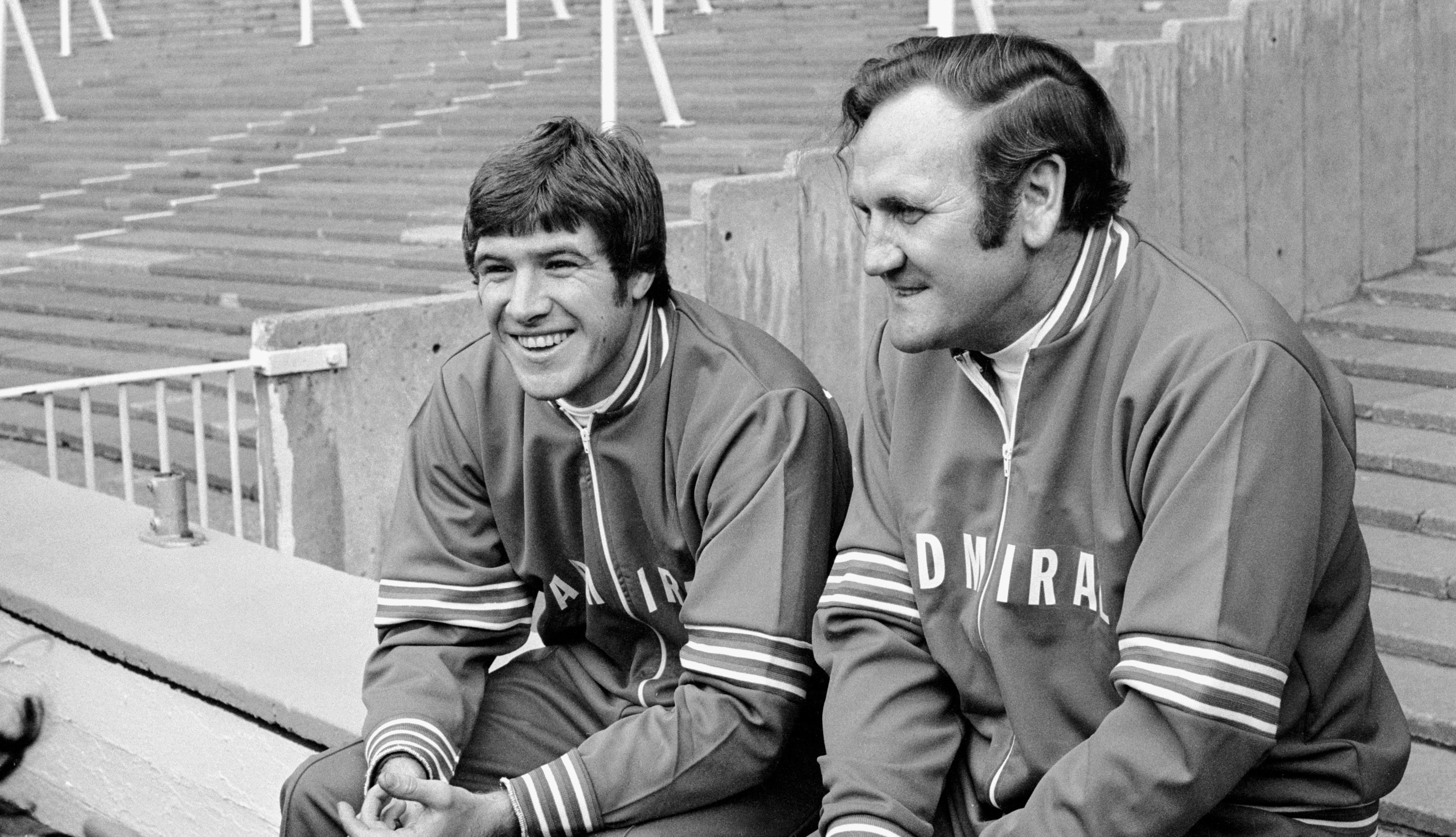

Not that Liverpool looked back. Paisley was even more successful than his predecessor, despite the avuncular north-easterner’s first team talk being: “I never wanted this bloody job, but it looks like you’re stuck with me.” A famously cuddly contrast to Shankly’s brusque wit, Paisley nevertheless possessed an astonishing football brain, and went on to mastermind six league titles, three League Cups, one UEFA Cup and three European Cups in his nine years at the helm.

But one of his Paisley’s most famous quotes – “I’ve been here through the bad times too – one year we came second” – was true of his debut season in 1974-75. The Anfield side finished two points off the top and only three points clear of seventh-placed Middlesbrough, with Ipswich, Everton, Stoke and Sheffield United also involved in a remarkably close title race.

However, the battle of the new gaffers was won by the least high-profile appointment, Mackay at Derby. A Clough signing for County, the Scot was arguably as effective as Old Big ‘Ead at the Baseball Ground.

After winning the league playing football to rival anything Liverpool produced, the following season he got County to an FA Cup semi-final, and was unlucky to be eliminated from the European Cup by Real Madrid. Mackay deserved longer in charge at Derby than he got, but after a poor start to the 1976 season, the axe fell. A Division Two title and Championship play-offs apart, the club have won nothing since.

So what can 2013’s incoming and outgoing men of management learn from history? And how do we crudely compare the generations?

The parallels between Shankly and Ferguson are obvious: Scots, socialists and firebrands who revolutionised reds (loyalists may deny it, but in a parallel universe, Shankly would have been a fine United manager, and Fergie worshipped by Kopites).

Fears that Sir Alex may go a bit Harold Bishop and end up wandering in to Old Trafford in his pyjamas, or that heartbreak will usher him to an early grave, however, seem unjustified. At 71, he is retiring 13 years later than Shankly, and has a richer life outside of football.

The shadow is more likely to loom over Moyes: should United be trailing 2-0 at home in a Champions League fixture, the temptation for the cameraman to focus on a watching Fergie, and for Clive Tyldesley to utter: “a penny for his thoughts”, will be overwhelming and depressing.

Moyes won’t get as much time as Shankly or Ferguson were afforded to succeed, but then he takes the tiller of a fully functioning ship – an inheritance similar to Bob Paisley’s.

The man most likely to mirror the colossal self-publicising of Clough, or get sacked after 44 days for doing or saying something bonkers? Step forward Jose Mourinho – although he’ll be going some to manage that at a place where fans and players worship him. In many ways, Rafa Benitez’s Chelsea cameo was The Damned United with a happy ending: a man loathed at a club he’d previously disrespected, who managed to leave Stamford Bridge mildly admired.

All of which leaves Manuel Pellegrini, the least-known and least focused upon, in the role of Dave Mackay: tasked with replacing a fan-loved figure who also brought long-craved success to an underachieving outfit, while ruffling a ton of feathers.

But whoever gets sacked, whoever has meltdowns, whoever dies, or chins a fan, or wins the Champions League, 1974-75 shows us that it’ll be unpredictable – and essential viewing... even if we don’t get Sky’s presenters cavorting under a glitterball.

Nick Moore is a freelance journalist based on the Isle of Skye, Scotland. He wrote his first FourFourTwo feature in 2001 about Gerard Houllier's cup-treble-winning Liverpool side, and has continued to ink his witty words for the mag ever since. Nick has produced FFT's 'Ask A Silly Question' interview for 16 years, once getting Peter Crouch to confess that he dreams about being a dwarf.