How the Premier League breakaway happened: The first season of 1992/93, as told by its heroes

In 1992, a group broke away from Division 1 to form a brand new league with an exciting revenue model. With the Premier League now over 30 years old, FourFourTwo remembers the first-ever Premier League season

Today marks 30 years of the Premier League: on August 15, 1992, the first round of Premier League matches were played – signalling the end of 104 years of the supremacy of the Football League. Here's how it all happened...

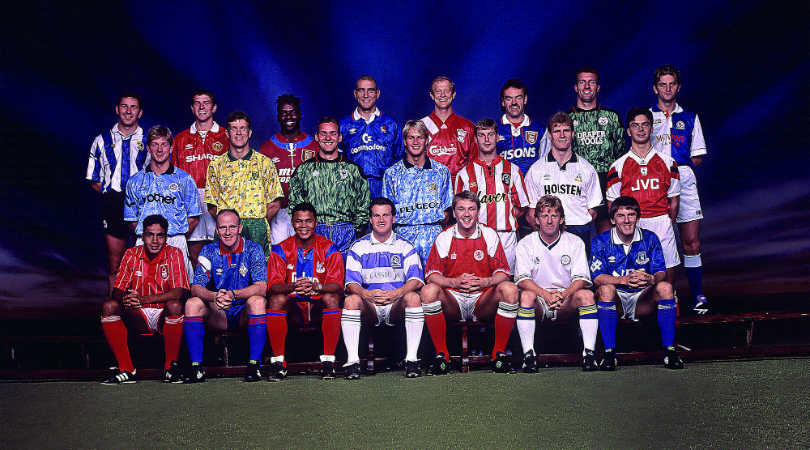

Leeds United midfielder Gordon Strachan and Oldham’s Andy Ritchie marshal David Hillier, Gordon Durie, Alan Kernaghan (of Arsenal, Tottenham and Middlesbrough respectively) and 17 other footballers representing each top-flight team from a hotel onto a coach.

Safely on board, Ipswich defender John Wark and Southampton goalkeeper Tim Flowers swap jokes, while Tim Sherwood of Blackburn looks a bit pensive, blissfully unaware of the gilet-loving banter cliché he will later become. While inside a shiny television studio, Chelsea’s hatchet man Vinnie Jones sashays front and centre of a photoshoot, with Ian Butterworth from Norwich, Ian Brightwell (Manchester City) and Peter Beardsley (Everton) looking on. The brooding keyboard, interspersed with the odd electronic blip, builds.

“You turn me on!” yelps the unmistakably earnest clarion call of Jim Kerr from Simple Minds’ 1985 hit Alive and Kicking, as Arsenal’s Swedish midfielder Anders Limpar is given some breakfast in bed from (presumably) his wife. Team-mate David Seaman makes a save in his back garden. Cut to a changing room and Jones, Durie, Sherwood and John Salako are all having fun in the shower…

Aston Villa winger Tony Daley and Wark pump iron. New Tottenham signing Darren Anderton performs a few sit-ups. A bewildered Strachan looks quizzically at a pair of trainers. Jones, still shirtless and warming to his future Hollywood career, re-imagines a hairbrush as a moustache.

Transported to White Hart Lane, Anderton and Porsche-driving Paul Stewart mingle with fans, N17’s answer to a depleted New Kids on the Block. One petrified young supporter is helped up onto a police horse. Man City manager Peter Reid implores his team “to get that ball back as soon as we can” in a nondescript dressing room. Emboldened by Reidy’s “all the very best, boys”, 22 actors (you never get to see their faces) run down a tunnel in club colours and out into the blinding light, as Kerr’s seminal lyrics crescendo to “ba da da dah dah dah, ba da da dah dah dah”.

“The FA Premier League…” then declares the baritone voiceover – as a long-haired player, suspended against a sunset, leaps very high to head a football – “live, only on Sky. It’s a whole… new… ball game.”

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Thirty years ago, in August 1992 – two years before FFT drew its first breath – Sky marked the new Premier League era with an advert so ’90s it could have come doused in Lynx Africa. Careering into view amid a backdrop of half-built post-Taylor Report stadia, garish blazers and cheerleaders emerging from some oversized Christmas crackers, the replacement of the old First Division was barely recognisable from today’s multi-million-pound behemoth full of the world’s best players.

Talk of a breakaway from the Football League wasn’t anything new. The Big Five clubs (Manchester United, Everton, Liverpool, Arsenal and Spurs) had first discussed the possibility of the split with Greg Dyke – then the managing director of ITV and later the FA chairman – in October 1990, and a deal was eventually reached with the entire 22-team division in February 1992.

The top-flight would now retain all money from a yet-to-be-agreed exclusive television rights deal, instead of having to divide it equally with the rest of the Football League. For their part, the FA stated they were acting in England’s interests because the new Premier League would be reduced to 20 teams within two years to avoid World Cup exhaustion. They omitted to mention that 14 of those 22 top-flight clubs had already signed up to an independent breakaway anyway.

Almost immediately, the PFA threatened to strike, concerned that clubs, not players, would be the only ones to profit.

“To a man, we were all willing to back our union, as it was something that would benefit everyone, in the same way you had the miners in the ’70s,” the former Sheffield United striker Brian Deane tells FourFourTwo. “They convinced us this was the right thing to do. I don’t really want to talk too much about the PFA, but I think that we were all in the right.”

Tony Cottee, then of Everton, agrees.

“I wouldn’t say we were taken advantage of, but there wasn’t a fair split of the money,” Cottee tells FFT. “We wanted to be fairly rewarded for what we put into the game. The wages compared to what the clubs earned weren’t relative. There was going to be more money in the game, so I don’t think there was anything wrong with it. Things have probably gone a little too far the other way now...”

"Future sold for pie in the sky"

Strike averted, the next stumbling block was the deal for exclusive television rights. With Dyke central to the Premier League’s existence, ITV were the early frontrunners, proposing £84 million across four years. Offer and counter-offer between ITV and a joint BSkyB and BBC bid (for both live rights and highlights) soon followed until Premier League chief executive Rick Parry arranged a meeting at London’s Royal Lancaster hotel on May 18 for all chairmen to vote.

Backed by BSkyB’s Rupert Murdoch in his joint takeover of Tottenham, Spurs chairman Alan Sugar contacted the satellite broadcaster’s chief executive Sam Chisholm from the hotel lobby, instructing him to “blow them [ITV] out of the water”. Sky bid £304m over five years, for 60 live games per season. They won a majority by just one vote, Sugar being allowed into the ballot despite a vested interest that his own company Amstrad made the satellite boxes for Sky.

“Future sold for pie in the sky,” said the Guardian. They weren’t alone. BSkyB was currently losing £10m a week.

“Sky came at the right time for football,” Andy Melvin, Sky’s executive producer of football in 1992, later told FFT. “When we started, the BBC and ITV were in the comfort zone.”

Melvin’s brief – given to him by the director of sport David Hill, a spiky Australian who had revolutionised the coverage of cricket Down Under – was simple. “David handed me this blank piece of paper,” Melvin later explained. “He said: ‘My order is just to make this really fucking good’ – so I was like a kid in a sweet shop.”

By 1993, Sky recorded a £63m profit. In February 2015, they paid £4.2 billion for their share of the television pie.

Not-so-humble pie

The “whole new ball game” advert was Sky’s first attempt at giving football its mass appeal. Every top-flight club featured, the focus on trying to attract a family audience.

“That’s where it all began,” recalls Darren Anderton, who had joined Tottenham from second-tier Portsmouth that summer for £2.5m and missed the first photoshoot because he was on holiday in the US. “It was pretty daunting to be asked to do the advert and interviews every week, but it was great fun. I’m fortunate to have been there while the league changed. It was very special.”

Former Aston Villa winger Daley, who spends much of the advert shirtless and holding dumbbells, agrees. “It must be one of the most homo-erotic things ever seen on TV!” Daley, who spent 10 years with Wolves as strength and conditioning coach, tells FFT with a chuckle. “I got so much stick for doing it. Even now, people at work see it, do a double-take and say, ‘what’s that?!’

“If it was done now it would be slightly different, but who knows? Maybe I owe my entire career to those few seconds on the advert!”

The first Premier League season began at 3pm on Saturday August 15, with Sky having to wait until the following day for their first live game. “There was a lot of publicity around the change,” recalls Sheffield United striker Deane. “There was a razzmatazz to everything; it was almost American with Sky getting a player from each team involved in the adverts and kits. We knew that this was the start of something.”

Even the Blades’ programme for their season-opener against Manchester United joined in the fun and games. Boss Dave ‘Harry’ Bassett dressed up as Santa, with Deane covered in tinsel and club captain Brian Gayle wearing a Christmas cracker hat. Why?

“Harry said that we only started playing well after Christmas, so if we had the party before the season started then we would be ahead of the curve,” says Deane. “Turkey, all the trimmings. It was just a bit of fun, but we had a great team spirit.”

Spurred on by festive thoughts, despite an unseasonably hot day in Yorkshire, Deane scored after only five minutes after ghosting in between Manchester United centre-backs Gary Pallister and Steve Bruce from a long throw-in to register the new league’s first goal.

“We’d been working on that set-piece all summer so that was the most pleasing thing at the time – it wasn’t the most spectacular goal,” says Deane, who also got the second in a 2-1 victory. “One of the lads told me that it was the first one in the Premier League. I had no idea. There were a lot of very good players around: Mark Hughes, Alan Shearer, Teddy Sheringham, Ian Wright. So to get the first ever goal, and be associated with those players, was a proud moment for me.”

Head in the Sky

The following day, Sky had their first chance to show what live Premier League football could offer, as Liverpool travelled to Nottingham Forest. No more mowing the lawn or afternoon walks – Super Sunday was born.

“The build-up was unbelievable,” Forest keeper Mark Crossley tells FFT. “It was like going into an FA Cup final, a family show, instead of a normal league game on a Saturday afternoon. The Trent End was only half-built at the time, and all of a sudden you had millions of viewers worldwide and a guard of honour from some cheerleaders...”

Sky were certainly keen to play to the crowd.

Teddy's big goal at 0:40

“Football will never be the same again,” exclaimed Richard Keys, who had moved across from his weekday morning cuddle-fest on TV-AM in a two-sizes-too-big bottle green blazer along with a pastel-coloured tie.

Five hours of coverage – punctuated with favourable comparisons of the pitch to Keys’ front lawn, plus some delicious primary colour credits and synth-pop soundtrack – from the City Ground would follow. Teddy Sheringham cut inside from the left-wing to score the game’s only goal past Liverpool’s new goalkeeper David James.

“Yeah, it gets mentioned every now and then!” Sheringham tells FFT. “Even 25 years on people talk me through it. It’s something nice to be remembered by, especially as it was a good goal, but you didn’t know how big it was all going to become back then. Three games later I’d been sold to Tottenham [for £2.1m] where I won the Premier League’s first Golden Boot, which I’m also very proud of. The live games and the dancing girls gave everything a little bit of pizzazz. Mind you, so did Richard Keys’ jackets and his dodgy barnet...”

But it was on Monday Night Football that Sky really sought crossover appeal, beginning with Manchester City’s 1-1 draw at home to QPR.

“Mondays are now officially part of the weekend!” cheered Keys, his attention drawn to the Sky Strikers cheerleaders dancing around some fireworks. “Impressed with what’s going on in the centre circle, boys?”

Keys, Andy Gray and Chris Waddle may have been that night – the less said about which, the better – but things seemed a little contrived. Match balls arrived courtesy of parachutists, while the pre-game and half-time entertainment from washed-up pop bands earned mixed results over the course of the whole season. Scottish electro-rockers The Shamen were mercilessly booed off at Highbury, while Curiosity Killed the Cat’s decision to wear Chelsea shirts before Southampton’s 1-0 home defeat to Manchester United at the end of August went down as well as you would probably expect. Whether that unpopular performance contributed to the band’s split just a month later is mere conjecture.

It’s a knockout

Seven days after Curiosity’s Dell death throes, the heavyweight boxer Lennox Lewis arrived at Carrow Road for Norwich vs Nottingham Forest. “My favourite teams are Arsenal, West Ham and Crystal Palace,” said the future world champion, before turning his attention to Brian Clough for a pre-match prediction. “Nottingham, because I like the manager. He’s kinda funny.” The Reds lost 3-1.

“One of my first games for Tottenham was a live game at Coventry on a Monday night,” Anderton remembers. “My only previous experience of playing on television was the FA Cup semi-final against Liverpool the season before for Portsmouth. It was such a novelty to have that level of entertainment on the pitch before a bog-standard league match.”

Perhaps Sky’s best football offering came from Andy Gray’sBoot Room, where the former Everton goal-getter would sit in front of a Subbuteo pitch and talk through the previous weekend’s tactics. Sound familiar? “Andy and I were drinking one evening, he was on Rolling Rocks and I was on San Miguels,” Sky’s then head of football Andy Melvin later told FFT. “The brown bottles were defenders and the green ones were attackers, and we were aware that a few people were watching and listening in.

“Football tactics should be discussed in a grown-up way and so Andy Gray’s Boot Room was introduced, and that then inspired the tactical discussions on Monday Night Football.”

The change to a much more serious product was welcomed by many. “They had bands, obstacle courses with people running through silly gates,” then-Oldham manager Joe Royle tells FFT. “They soon realised it didn’t work and that fans are serious. The whole game was exploding. If you want the money, you’ve got to do what you’re told – it’s quite simple. We’d had some Sunday cup games and the occasional Friday night match, so it wasn’t particularly new. There was just plenty more of it.”

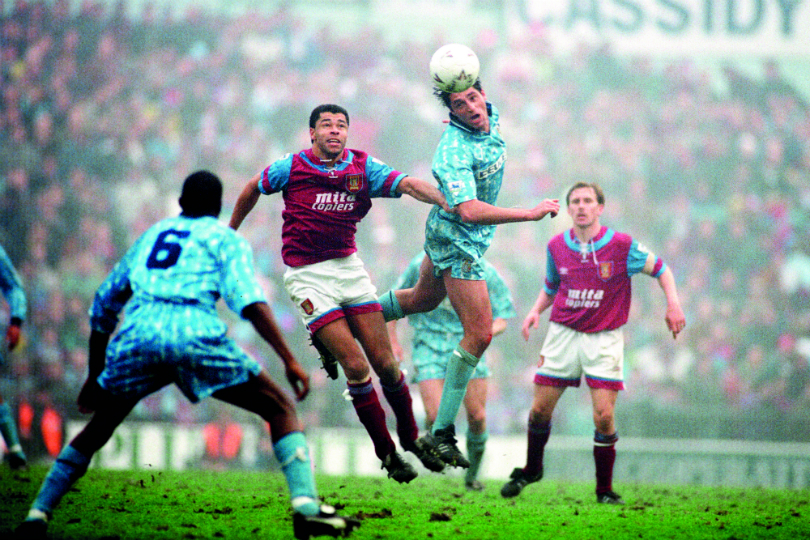

Matches in front of the live cameras brought their own allure, too. “The lads were always at the mirror before a TV game, jostling for space,” recalls Villa’s Daley. “To be honest, it’s not any different now! It was a novelty for all of the lads. You could feel the sense of more people watching you because of the cameras. Everyone wanted to go out there and try to do their best.”

And the players quickly adapted to their revised matchday routines. “It was unheard of to play at 4pm on a Sunday, or 8pm on a Monday night, but you just had to get on with it,” recalls Cottee. “Playing-wise it was still business as usual for us. The thing was, teams can now get a private jet back from matches. If we had a long away trip back to Everton on a Monday night, we’d be back on the coach home. We’d stick a load of beers on the coach, stop for some fish and chips and you’d be great. That’s the way we all lived and we got on with our football.”

It wasn’t exactly the ‘win or lose, always on the booze’ days from the 1970s, but socialising remained an essential part of the scene during 1992/93 Premier League football.

“We would regularly go out on a Saturday night for a few drinks, often on a Tuesday, too, if you had the Wednesday off,” reveals Forest keeper Crossley. “It wasn’t like you were committing a crime, that was just the norm. Fans would mix with the players as well. It was common sense. If you weren’t playing well, you wouldn’t go out. You can’t do it now – players are more like role models.”

Gradually, things began to change.

“It was just tradition,” says Daley. “Foreign players were a big part of that and there was a shift towards professionalism, with more sports science and fitness coaches that came along with them. You had to be able to move along with the times.”

Nowhere was that shift more keenly felt than at Manchester United. In 1991/92, the Red Devils lost the title to Leeds at the death, having played four games in seven days. Defeat to Aston Villa at the beginning of November 1992 left Alex Ferguson’s men 10th in the Premier League. “We were still reeling from the previous campaign,” centre-back Gary Pallister admits to FFT. “We were trying, maybe a little too hard, to right a wrong and missed out on putting the pressure on our rivals early on.”

Ferguson took his “last gamble in charge” according to the Liverpool defender-turned-pundit Emlyn Hughes, and recruited Leeds’ mercurial Frenchman Eric Cantona – one of 13 foreign players to feature during the first Premier League season, already labelled a “plague”. As Fergie later recalled: “He stuck his chest out, put his collar up and said, ‘look at me.’”

“We weren’t too sure, initially,” Pallister remembers, especially when Cantona constantly refused afternoon offers to play snooker. “He’d had a colourful career, to say the least, and we weren’t really sure how well he would integrate, given his reputation as a fly-by-night sort of player. But he was just a different class. He was the final piece of the jigsaw. First to training, he’d stay behind to do crossing and shooting every day. He was a consummate professional.”

It didn’t take long for that attitude to rub off on United’s youngsters. Ryan Giggs, who would go on to win the PFA’s Young Player of the Year, had scored an incredible solo goal against Spurs in September, but was struggling for consistency. Cantona soon became Giggs’s hero, because the Frenchman could spot how quick an opposition full-back would be in the warm-up. United only lost twice more for the rest of the season.

“Eric set the standard,” another of those youngsters, Lee Sharpe, tells FFT. “He had this arrogance, an air of class that a group of us teenagers or 20-somethings were in awe of. His ability was without question but it was also his attitude. Training was always at a game-pace with him.

“I can remember at the end of a couple of nights out, even though he didn’t really drink, we ended up having a chat about his philosophy. He psychoanalysed every game, so understood what he did well and what he didn’t do. It fascinated me. When things got a bit nervy, he was the one bloke you knew would unlock tight defences and create the one bit of magic that we needed.”

Yet, even the institutionally prehistoric were embracing the nascent, initially foreign, concept of marginal gains. Step forward the Sheffield United gaffer, Dave ‘Harry’ Bassett.

“Harry knew he had to be creative because we didn’t have the budget or talent, so he looked for any kind of edge,” recalls ex-Blades forward Deane. “He introduced us to psychologists, better nutrition and better conditioning. It was revolutionary. I know we were the first to do that sort of thing, because the guys that came in got jobs at three or four other clubs off the back of what they’d been doing at Sheffield United.

“The margins were much bigger then. Those changes might have given us 10 per cent, whereas now you’re only looking at 0.5 per cent because it’s become normalised. That was the difference between us staying up and going down.”

Indeed, the established order struggled in general. By the turn of the year Sheringham and Anderton were yet to really hit top gear at Spurs, while Arsenal were down in ninth and Liverpool languishing in 10th.

“The club was going through a transition,” Liverpool captain John Barnes tells FFT. The Reds’ campaign came to be defined by Ronny Rosenthal’s open-goal miss against Aston Villa in September. “Players were moved on and their replacements brought in too soon. Other clubs were spending the Premier League money, which meant they were able to compete with us.”

It certainly worked for fourth-placed Blackburn Rovers, for whom British-record signing Alan Shearer had scored 16 goals by the start of 1993. Table-toppers Norwich, meanwhile, were riding the crest of a wave.

“Norwich were a selling club who were never going to chuck big money at a mid-season signing to try to win the title,” striker Chris Sutton later recalled. “We had finished 18th in the previous season and only stayed up by three points, so when we got to 30 points in November we were all just thinking, ‘great, we’re not going down’.”

It was during those winter months, with the evenings closing in, that the Premier League struggled to escape the shackles of the old First Division, regardless of the change of name. Pitches deteriorated to ploughed fields, kits continued to resemble Jackson Pollock acid trips – a canary clearly having done its business on Norwich’s effort – and the fans voted with their feet. On January 26, just 3,039 people watched Wimbledon host Everton at the Dons’ temporary Selhurst Park home on a bitterly cold Tuesday night. It remains the Premier League’s smallest ever attendance. The difference between the top flight’s haves and have-nots was apparent.

“It was an eerie atmosphere, because Selhurst is a pretty big ground,” recalls Cottee, who scored twice in a 3-1 win for the Toffees. “Whether it’s a claim to fame to score two goals in front of the lowest Premier League crowd, I don’t know!

“It’s a pretty amazing stat to look back on now, when you think that Bournemouth have got the smallest ground but sell out 11,000 every week. It summed up Wimbledon. Plough Lane was very intimidating and it was to their immense credit that they stayed up for so long.”

Indeed, what Cottee remembers most from that particular evening was a good old-fashioned tear-up involving Everton’s midfielder Ian Snodin and the Dons’ team.

“It’s one of the funniest things I have ever seen on a football pitch,” he laughs. “He slid in and sliced someone in two, so he deserved to get a kicking. We all piled in, then Snods starting crawling out on his hands and knees while everyone above him is going at it. We saw a picture of it at training the following day and all laid into him. ‘Snods, you started all this, what are you doing crawling out of it?!’”

It wasn’t just apathetic fans that resulted in low attendances. Since Lord Justice Taylor’s 1990 recommendation that all major stadia should be all-seater after the Hillsborough disaster, half-built stands were the norm. With clubs now finally able to afford the necessary improvements thanks to Premier League cash, more than half the 22 top-flight teams played in 1992/93 while work was carried out.

“It was strange,” says Cottee. “It did affect the atmosphere, as you’re only playing to three sides of the ground. For the home team it wasn’t good, but for the away teams it spurred you on.

“I understand why it all had to change – I was playing in that other semi-final [for Everton against Norwich] when Hillsborough happened, but it would be good to get safe standing back into England one day.”

Eager for their players to attack something resembling a group of supporters, Arsenal famously erected a mural while Highbury’s North Bank was being redeveloped. However, devoid of any black faces, or women, the club came in for criticism over it.

“People act unthinkingly in this way all the time,” said a spokesman for the Commission for Racial Equality. “This is a club with the league’s premier striker, who also happens to be black [Ian Wright]. One would think that they’re now conscious of the issues.”

The Gunners won eight of 21 home games, opposition players even raising their game when attacking the mural.

“On my first game back from an injury I scored the winner in front of the mural!” laughs Villa’s Daley. “I was absolutely buzzing. It didn’t do me too much harm.”

Indeed, it was keepers who struggled the most with half-built stands. “It really affected me psychologically,” Forest stopper Crossley says. “I felt a bit lost, because the Trent End was where all the noisiest fans gathered. Even your markings and movement were affected as there’s no one stood behind you.”

A statistic is born

It was perhaps no coincidence that Crossley made history during that season at Southampton’s Dell, a ground which saw very limited change. On March 24, he became the only player to save one of Matt Le Tissier’s 48 professional penalties. “I’m still living off that!” laughs Crossley. “It was only years later that I knew I was the only goalkeeper to save one. I always went off instinct. Fortunately, I went the right way that day.

“He hit it well enough, but it wasn’t quite in the far corner and he put the rebound over. He was on 99 Southampton goals and always says he didn’t want the 100th goal to be a penalty!

“When he was inducted into the hall of fame, his agent got hold of me and they set up a goalmouth. Near the end of the evening, I was waiting behind a curtain and he was given the chance to finally redeem himself. This time he went the other way, and I saved it again! To be fair, though, he only had a pair of shoes on.”

It’s to Crossley’s credit that the keeper independently brings up his other Premier League first. “I scored the division’s first own goal as well,” he smiles. “We were at Blackburn and Colin Hendry got a header down to my left, I lost the ball and it went in. I'm less proud of that one!”

Watch highlights of that inaugural campaign and one thing becomes clear – that Hendry header was not in isolation, as goal after goal came from crosses into the box.

“That’s the English mentality – for the striker to run across your front man and get on the end of it,” explains Sheringham, whose partnership with right-winger Anderton began to blossom during 1993. “That’s not always been the case in Italy, Spain or France, who all tend to play a bit trickier. The game has evolved now, and your traditional English, burly centre-forward – such as Alan Shearer or Les Ferdinand – have become a dying breed these days.”

Sheringham believes that the treatment of centre-forwards has also changed – for the better. “Every team had a centre-half nutcase trying to kill you,” he reveals. “Defenders can’t do that any more and have to read the game much better. It’s for the good of the game that players now stay on the pitch and show their quality.”

One foe in particular sticks in the mind of former Chelsea forward Tony Cascarino. With Ian Porterfield the Premier League’s first ever managerial casualty in March, Blues legend Dave Webb took charge until the end of the season. Cascarino came back from international duty with Ireland with eight stitches in his knee. High-flyers Blackburn awaited on Super Sunday.

“I was up against Kevin Moran and he kicked the shit out of me all game, just like any time I played him,” laughs Cascarino. “It was on the telly so I really wanted to play, and the stitches came out during the game! Webby just said, ‘It’s only a flesh wound, get on with it!’”

By April, the Premier League’s maiden title race would be between Manchester United, Aston Villa and Norwich, the latter’s unexpected challenge effectively ending with a 3-1 defeat against the Red Devils.

“We blitzed them,” United defender Pallister remembers. “They were pushing us really hard and we played our best football of the season.”

Next up for United were Sheffield Wednesday at Old Trafford and the most notorious period of injury time in Premier League history. With United 1-0 down with four minutes to go, captain Steve Bruce scored two headers to spark wild celebrations – not least from the assistant manager Brian Kidd, who fell to his knees on the pitch – and a 2-1 win. ‘Fergie Time’ was born.

“Everyone forgets that the referee pulled a calf and it took an age to get a replacement from the stands – that’s where your seven minutes of injury time comes from,” says Pallister, whose deflected cross set up Bruce’s winner. “That was our season’s defining moment. A year earlier, we’d dominated Forest at home but lost. We thought that history was repeating itself, because we couldn’t score before Brucey finally popped up. To win that match seven minutes into stoppage time was a sign.”

United kept on winning. When Villa lost to Blackburn and Oldham in successive weeks, the game was up.

“We just lacked that experience of challenging at the business end of the season,” recalls Villa’s Daley. “It was the fear of the unknown for us, but we’d had a great season.

“Paul McGrath was absolutely awesome that year. He barely trained because of his bad knee, but he was incredible. He’d had his problems in the past but was rightly voted as the PFA Players’ Player of the Year.”

That Oldham defeat meant United had won the inaugural Premier League without even kicking a ball.

“Fergie was on the golf course when he found out. He’d told us not to watch, but we didn’t listen,” Pallister says. “Half an hour after the match, Steve Bruce rang around the squad, saying that we could all go round his house for a couple of beers. That lasted until 4am. It was a bit of a heavy one, considering we had Blackburn the following day!”

United still won 3-1, ending a 26-year wait to become English champions.

“It was all about laying that ghost to rest, rather than winning the first Premier League,” says Pallister, who scored United’s third from a free-kick. As inaugural champions, the squad each won miniature replicas of the trophy, not a medal.

“I was the only first-team regular not to score, so I pushed all of the other lads out of the way and smacked it into the bottom corner. It was probably the night before’s beers that made me do it. I turned around and shouted, ‘I can’t fucking believe it!’ When I got home, I got a clip round the ear from my gran. ‘I can lip-read, you know!’ she said. The atmosphere that night was the best I ever experienced at Old Trafford.”

That week, the squad went to Chester races “and didn’t see a horse for the entire time that we were there” from the champagne enclosure, before beating Wimbledon on the final day. Eric Cantona was mobbed as the Dons doubled their biggest attendance of the season. Eighty per cent were United supporters, many of whom had made the journey from Manchester to south London.

That Saturday also witnessed the Premier League’s first great escape. Beginning with that 1-0 victory away at title-chasing Villa, Joe Royle’s Oldham won three games in eight days to stay up, including a final-day 4-3 victory against Southampton. The Latics needed to better Crystal Palace’s result at Arsenal to survive.

“There were so many radios around the dugout, you couldn’t not be in touch with what was going on at Highbury,” says Royle. Palace lost 3-0. “In true Oldham fashion, we made life difficult for ourselves. We were winning 4-1 but then Matt Le Tissier started scoring some silly goals and we ended up hanging on. The referee played five minutes of injury time – I was running up and down the stairs by the dugout so often he was even laughing at me – and the pitch was atrocious. They had a late penalty shout but we did it. Palace went down with 48 points, still a record. I rang Steve Coppell up the following day and he said to me: ‘I just had a funny feeling, Joe, that we wouldn’t do it.’”

Middlesbrough and Nottingham Forest hadn’t even made it that far. Despite that opening-weekend victory against Liverpool, Forest’s 2-0 home defeat to Sheffield United in their penultimate match meant relegation for Brian Clough in his retirement campaign. Old Big ‘Ead’s farewell – wearing his trademark green sweater, his pockmarked face by then ravaged by alcoholism – at the City Ground was pure emotion.

“He would have retired if we’d won the FA Cup in 1991 – we all knew his health was deteriorating,” explains Forest’s Crossley, who watched from the bench having been dropped for an off-field misdemeanour. “I’ll never forget sitting there watching the 5,000 Sheffield United fans singing Brian Clough’s name. There were tears in Clough’s eyes as he went. There were some in mine, too.”

“Can I have a word from you, Brian?” asked one desperate television reporter, as the two-time European Cup-winning manager departed the stadium for the final time in 18 years.

“Of course,” said Clough. “Goodbye.”

The entertainment served up in the first Premier League season set the tone for what it has become. The day before Arsenal beat Sheffield Wednesday in the 1993 FA Cup Final, Spurs chairman Sugar sacked de-facto manager Terry Venables because he “knew nothing about the commercial side of the business”.

“All I could think was, ‘Why?’” says Anderton. “Terry had brought me to Spurs and believed in me. I was devastated.”

Anderton’s team-mate Sheringham concurs. “We all felt something really good was coming,” he says, “especially because me and Darren were telepathic at times. And even now I just want to pass the ball to him in charity games, because I know exactly where he wants it and vice versa. It was a huge surprise to me. It was simply a business decision.”

A bitter High Court battle for the club’s soul soon followed. Sugar won it, but not before dragging football’s reputation through the gutter with claims about transfer bungs. Football had become serial front-page news fodder, a mushrooming business increasingly fought over by the broadcasters, consumers and investors from foreign lands.

“There is no comparison to be made between 1992 and now,” says Cottee. “Not one single thing. You could argue that the ball is still round, but even that was totally different back in 1992. Stadiums are all-seater, pitches are immaculate, the money is on a different scale. The boots, the kit, training sessions, the diet and media. Maybe putting the ball in the back of the net still wins games. That’s it.”

Many people joke about being born 15 years too soon and question the beautiful game’s changing dynamic – or, in Daley’s case, lament the passing of the humble football moustache – but the truth is that no Premier League footballer from 1992/93 would change anything.

“It was a roller-coaster ride,” concludes Tony Cascarino. “When I left Chelsea in ’94, I was on £6,000 per week and remember thinking I was getting a great deal because I was nearly doubling my salary by getting £10,000 per week from Marseille. Two years later, most Chelsea players were getting about £20,000.”

If there is one club which encapsulates the Premier League’s 25-year journey, it is Chelsea. Stamford Bridge – open to the elements behind both goals, where players still parked their cars during matches – was decrepit and attracted no more than 10,000 fans a week. Their best player was Andy Townsend.

“We were a bang-average team, which had a few too many to drink and got into bit of trouble off the field too,” Cascarino says about those pre-Roman Abramovich days. “Now, people’s eyes light up when you say you played for Chelsea. Not one iota is it the same club I played for. Their season-ticket waiting list is now twice the size of what used to be our average gate. There’s a part of me that still misses that down and dirty link with the fans.

“Before my first day at the club, Andy Townsend said to me: ‘We meet in a café, just around the corner from the training ground.’ I arrived and the whole squad were tucking into a fry-up inside this battered caravan being propped up on bricks.”

When Sky boldly proclaimed ‘a whole new ball game’ back in August 1992, they weren’t joking.

Celebrate England's Euro 2022 victory by subscribing to FourFourTwo and getting three issues for £3

Andrew Murray is a freelance journalist, who regularly contributes to both the FourFourTwo magazine and website. Formerly a senior staff writer at FFT and a fluent Spanish speaker, he has interviewed major names such as Virgil van Dijk, Mohamed Salah, Sergio Aguero and Xavi. He was also named PPA New Consumer Journalist of the Year 2015.