Keane, McCarthy and a divided nation: Ireland's 'Princess Diana moment' at World Cup 2002

The Republic of Ireland's first World Cup appearance in eight years was a mere footnote to the explosive events which occurred on this day 16 years ago, as Miguel Delaney explains

Please note: This feature was originally published in June 2014

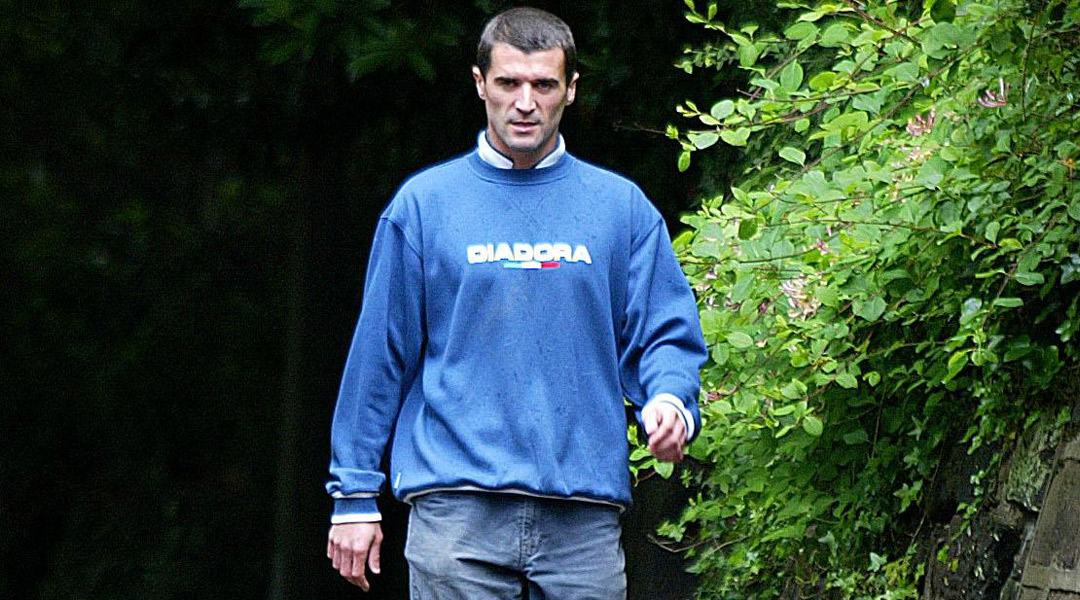

Roy Keane’s voice was actually beginning to crack and waver. For a few minutes, it seemed like that famously cast-iron will was about to give way too.

Much of the Irish nation, meanwhile, stood on edge. They were awaiting a moment that would decide the entirety of the team’s 2002 World Cup campaign – and it took place thousands of miles away from the stadiums of Japan and South Korea.

In Manchester on May 27 – just five days before Ireland’s first World Cup game for eight years, against Cameroon in Niigata – Keane had agreed to an interview with national broadcaster RTE. The captain’s initial decision for doing so was to set the record straight about what exactly happened on May 23, in the ballroom of Saipan’s Hyatt Hotel. There, a volcanic dispute between Keane and manager Mick McCarthy had seen Ireland’s most dominant player sent home.

Stick it

The parting shot has become legendary in its own right. It arrived after a decade of resentment between the pair – and one long and uneasy truce – had given way to Keane publicly criticising preparations, McCarthy confronting him about it in front of the squad while apparently mentioning the timing of certain injuries, and the captain detonating.

If World Cup camp cabin fever had played a part, and too much time in each other’s company had set the spark, Keane blew the door open: “Mick, you're a liar … you're a f***ing w***er. I didn't rate you as a player, I don't rate you as a manager, and I don't rate you as a person. You're a f***ing w***er and you can stick your World Cup up your a***. The only reason I have any dealings with you is that somehow you are the manager of my country! You can stick it up your b****ks.”

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Now, in a very different mood, Keane wanted to give his side of the story – particularly after the way Ireland as a country had been absolutely consumed by the event. Interviewer Tommie Gorman, however, decided to turn the exchange into something else. He tried to exhort Keane to go back.

The footage remains compelling, not least because Keane is so clearly on the verge of tears. This was not quite the unmoving monolith that had split a country. This was a man responding to all of Gorman’s references to compromise, to morals, to “all the little kids in Ireland” – even to the peace process in the north of the island.

“Is there a chance of you doing it again?” Gorman implored.

“The ball’s not on my side of the court now,” Keane responds.

It was an event that overshadowed every ball actually kicked by the team. The single noun of ‘Saipan’ has become shorthand for the entire campaign and all of the deep emotions it drew out. Despite an Irish tournament that featured two last-minute equalisers and a penalty shootout, these are the abiding memories. It is impossible to escape the lingering regret that there might have been even greater memories.

Ireland's "Diana moment"

Recently, Irish sports show Off the Ball devoted a segment celebrating the anniversary of Robbie Keane’s stoppage-time equaliser against Germany in that very tournament. It has a strong claim to be one of Ireland’s most historic strikes. Yet, even in that show, it kept coming back to an alternate history: to what would have happened had Keane played.

For a brief period, particularly in that Monday RTE interview, it looked possible. Keane ended, with his voice again wavering, simply saying: “I want to play for Ireland – we will have to see.”

It was impossible not to see him in the media, at the very least. For six days, the story led every news bulletin, and was on every front page. This was despite the fact that a general election had just taken place, and even saw returned prime minister Bertie Ahern offer to help heal the rift. He wasn’t the only one, as stories abounded of businessmen offering to put on private jets to return Keane to Japan the moment it was settled.

Clamour rose to just get Keane back. That feeling, though, was not universal. For some, the player had betrayed his nation. For the rest, less willing people had betrayed Keane. The debate adopted political and almost philosophical lines; about what a small country had a right to expect; about whether the player was a prima donna or the type of perfectionist needed. People were either on McCarthy’s side or Keane’s. The period was that intense, that animated. The volatility of the arguments about it were only matched by the depths of emotion on show, with people being filmed on TV openly weeping. One Irish Times editorial described it all as Ireland’s “Princess Diana moment”.

That was largely because of the deeply transformative effects of participation in Euro '88, Italia '90 and USA '94. The sheer jubilation was seen as a symbolic first departure from decades of economic misery.

Linchpin

In the time since, Keane had grown into the team’s singularly dominant player, with his unyielding attitude also put forward as representative of newly savvy Celtic Tiger Ireland. That was never more evident than in the qualifying campaign for 2002. He simply made McCarthy’s good young team so much better; proper competitors. Keane had been either the decisive or defining player in every game of consequence, not least the 1-1 home draw with Portugal – in which he and reigning Ballon d’Or holder Luis Figo were only scorers – and the landmark 1-0 win over Holland.

His notorious early challenge on Marc Overmars set the tone for the day. A famous picture by photographer Lorraine O’Sullivan fully revealed the tone of manager-captain relations. Amid the joy of victory, McCarthy and Keane shook hands, but the latter could barely look around.

They would not shake hands in the days before the Cameroon match. The anticipated entente never arrived. It didn’t even come down to whether one of them was big enough to be the first to say sorry, either. Indeed, the manner in which it all ended was almost appropriate, if also so unfortunate.

After a week of mixed messages and media chaos, and just after Keane’s conciliatory interview with Gorman, the Football Association of Ireland’s media department released a player statement backing McCarthy. The problem was that it was meant to be held back until after the manager himself had spoken, even though he now had so much to ruminate on.

That was it. Keane definitively withdrew. Ireland went on to draw three games out of four, and secure a respectable second-round elimination after a penalty shootout defeat to Spain.

What could have been

That, however, was just one of many ironies about it all. For one, Keane had been specifically railing against satisfaction at that kind of performance; of the perils of not adopting the right mindset. Secondly, it ensured this was ultimately a somewhat predictable end result – if after an erratic sequence of events – in a tournament famous for surprises and upsets.

With Keane in the team, Ireland could really have dreamt of reaching the semi-finals. Instead, he couldn’t reach a compromise. This was the tipping point of his tenacity. The ultimate winning mentality had become self-defeating.

Back in that interview, Gorman asked Keane whether, “in 15 years’ time, are you going to look back and ask yourself what it was all about?”

“There’s no doubt in my mind,” Keane responded.

It didn’t take 15 years. In 2013's celebrated documentary with Patrick Vieira, he expressed some regret. “To play in the World Cup... it would have been nice. A lot of people were disappointed, particularly my family.”

Disappointment and anger has now faded. An element of regret will always remain.

World Cup Wonderland: stories, interviews and more