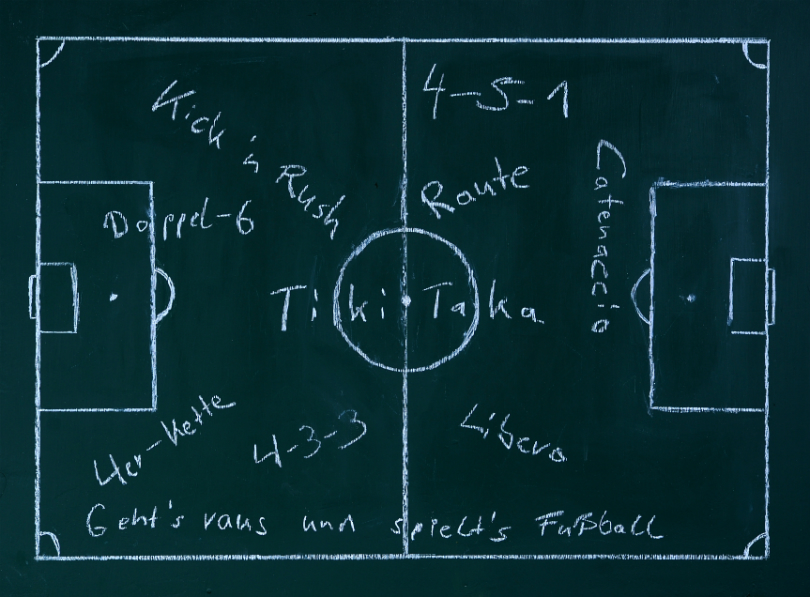

6 football tactics that changed the game as we know it

Tactical revolutions have come in various guises. Michael Cox guides you through the most impactful ones the game has seen...

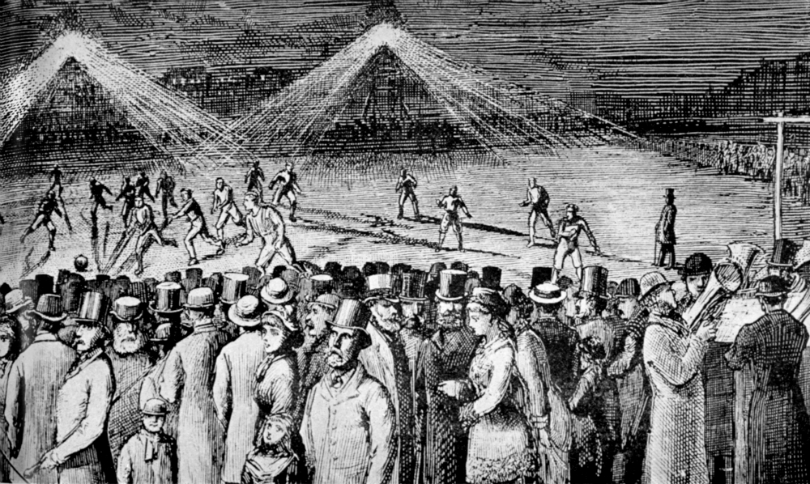

1. The combination game, 1870s

Early football games were based around dribbling. Players would receive possession and move directly forward in possession, with teammates largely concerned with ‘backing up’ to collect the ball if it ran loose

Modern football is largely based around passing, but it wasn’t always the default approach.

Early football games revolved around dribbling. Players would receive possession and move directly forward in possession, with team-mates largely concerned with ‘backing up’ to collect the ball if it ran loose. In terms of a player’s intentions when receiving the ball, football during the 19th century was arguably more similar to rugby league than modern football: passing was rare, and essentially a last resort.

An alternative approach, however, was being developed. The Queens Park side of the 1870s dominated Scottish football and provided all the players for their match against England in 1872. Although the English players were much stronger, and built for for a more rudimentary style of football, the Scottish players worked properly as a team, attacking in pairs and slipping the ball to one another on the run.

This approach was startling to the English players, unaccustomed to the concept – the idea that a ball could be deliberately passed to a team-mate in a better position had barely been considered. Inevitably, this combination game maximised the talent of players and created more of a harmonious team. Equally inevitably, the idea spread across Britain – and then the rest of Europe.

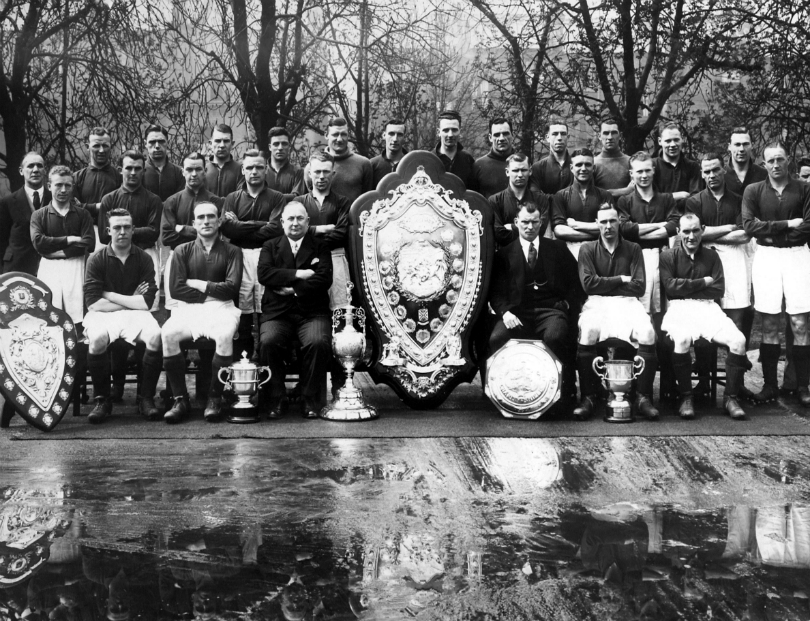

2. The WM, 1930s

While tactics and formation are sometimes used almost interchangeably, most significant tactical developments have been about style rather than shape. The WM, however, is an exception.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

The ‘pyramid’ system – essentially 2-3-5 – had reigned supreme until the mid-1920s, when a significant change in the offside law meant attackers required only two opponents between them and the opposition goal, rather than three. Early 20th century teams had understood the value of the offside trap, but the change made it significantly more difficult, and risky, to perfect. Teams could play forward much more quickly.

Arsenal manager Herbert Chapman realised that adapting to the new offside law was necessary. Chapman decided his centre-half – then referring to the player in the centre of the pyramid’s three-man midfield – would have to drop deeper, between the two full-backs, forming a three-man defence. This change the nature of defending entirely, and provided a more solid foundation for the rest of the side.

Because the centre-half’s retreat left the side short in midfield, the inside-forwards dropped back, leaving one centre-forward and the two wingers higher up the pitch. This became 2-3-2-3, or WM. Teams now had a sufficient number of players at the back, and had beefed up their midfield too – it was no longer all-out-attack.

3. Hungary’s positioning, 1950s

Hungary’s 6-3 thrashing of England in 1953 is one of the most famous games in the history of football – England were completely outwitted in a tactical sense. The crucial thing about Hungary’s performance was relatively simple: they confused England by deploying key players in roles which surprised England.

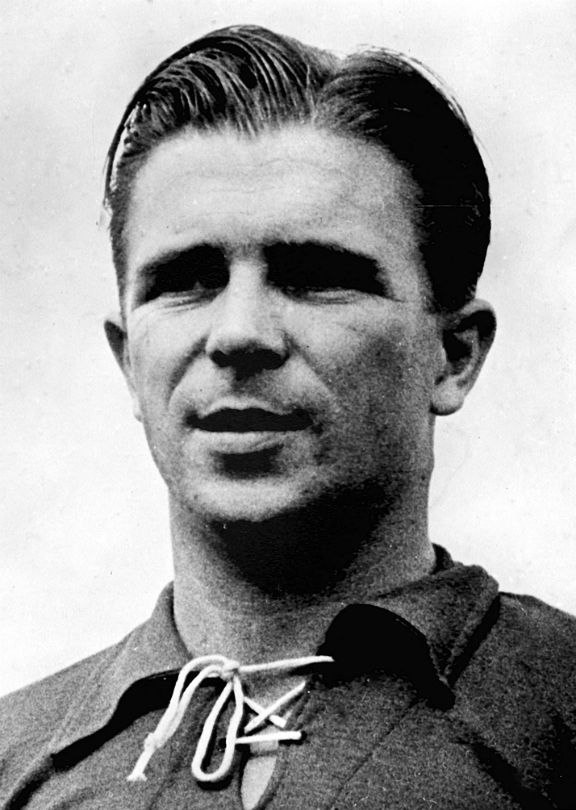

Though not the star man, centre-forward Nandor Hidegkuti was the catalyst for Hungary’s incredible performance. He wore the No.9 shirt, and therefore was expected to play as a striker, engaging in a physical battle with England’s central defender.

Instead, he dropped deep away from England centre-back Harry Johnston, dictating the game almost as an extra midfielder in oceans of space and providing regular passes to the other four forwards.

Defensively, too, Hungary did things differently. Jozsef Zakarias was a midfielder but dropped deep to become, essentially, a second central defender, pushing the full-backs wider into the positions they play today. This idea spread quickly, with a back four soon considered the default approach across the world. But Hungary’s achievement was greater than that, effectively popularising the art of getting attackers into space, rather than playing directly up against an opponent.

4. Catenaccio, 1960s

Herrera complained that teams who copied his system did so in a more defensive manner than they should, and focused entirely on the spare man in defence without an attacking full-back which allowed quick attacking

“Catenaccio” – meaning door bolt – is often used interchangeably with ‘defensive football’, but was actually a specific defensive system that changed the nature of how teams defended, and revolved largely around the concept of a sweeper.

While Austrian coach Karl Rappan was the first to experiment with a sweeper behind the line of defence, the Italian Nereo Rocco popularised it in Italy with Triestina, constantly changing his system but always maintaining the sweeper.

This led to Argentine coach Helenio Herrera using a similar system with Inter Milan. His version used a sweeper behind a back four, who were all given strict man-marking responsibilities and played extremely aggressive, physical football. The sweeper remained behind as a spare man, effectively an insurance policy.

Inevitably, this meant Inter were generally outnumbered higher up the pitch, and struggled to command the midfield zone or find overloads in attacking positions. Herrera complained that teams who copied his system did so in a more defensive manner than they should, and focused entirely on the spare man in defence without an attacking full-back which allowed quick attacking.

Nevertheless, many teams looked to outnumber their opponents at the back, and therefore concentrated heavily on not conceding.

5. Total Football, 1970s

Perhaps the most revered tactical innovation in the history of football, Rinus Michels’ 'total football' system he used with Ajax, Barcelona and the Netherlands exposed the limitations of man-marking.

In Michels’ teams, players didn’t have a fixed position, constantly interchanging to drag opponents out of shape. Footballers were expected to be capable of playing in defence, midfield and attack, creating an incredibly universal side: Holland started their defending from the front, and their attacking from the back.

While sometimes considered to be about players spontaneously moving where they pleased, in reality the approach was more systemised: players would generally swap positions in ‘vertical’ lines – a right-sided defender running forward, for example, would then be replaced by a right-sided midfielder. Lateral swapping was rarer.

Johan Cruyff was the posterboy for this style of football: theoretically a deep-lying centre-forward but wandering across the pitch into much deeper positions. His team-mates essentially responded to his drifts by moving into the vacated space. That was the key to the system – always finding space.

- Johan Cruyff: The player, the coach, the legacy

- How Johan Cruyff reinvented modern football at Barcelona

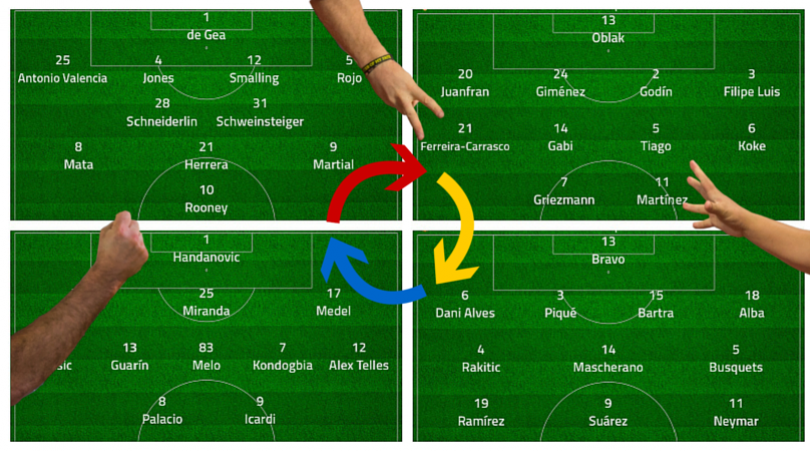

6. Tiki-taka, 2010s

There has arguably already been a backlash: counter-attacking teams are prevailing more over the past couple of years

You can trace the development of Barcelona and Spain’s modern football through all these tactical innovations, but between 2008 and 2012, they put more emphasis upon ball retention than any side in history.

Always determined to overload the midfield by deploying more players in that zone, Barça demanded to have control of possession. Counter-attacking was rare – they would often turn down the chance to exploit space and instead retain possession in central zones.

While Barcelona were unquestionably an attacking side, Spain used ball possession primarily as a defensive tactic. They won World Cup 2010 by scoring only eight goals in seven matches (one of them in extra time in the final) but were able to keep clean sheets in all four knockout matches. Soon, every side in Europe was concentrating on ball retention.

There has arguably already been a backlash: counter-attacking teams are prevailing more over the past couple of years, and even Barcelona have become significantly more direct. It remains to be seen whether tiki-taka has a lasting legacy, but the initial sudden craze for possession football demonstrates that football tactics continue to evolve – and always will.

RECOMMENDED