Howdy! How remortgaging a house saved the 1994 World Cup

It almost never happened. But off the back of one man's mortgage, the USA put on a record-breaking World Cup that changed football forever. Jamie Trecker tells the inside story

It's safe to say that the 1994 World Cup was the first ever to be funded by a home equity loan. Twenty years later, it's difficult to remember a time when USA 94 was thought to be a massive bomb waiting to go off. Plagued by shoestring finances and nearly torpedoed after a bitter rift between FIFA and a leading executive, it almost never happened. A mere $300 million later, 1994 changed not only the sport in America, but around the globe forever. And all because US Federation lawyer Scott LeTellier mortgaged his house.

Until 1994, soccer in the States was underground. Since the collapse of the North American Soccer League (NASL) in 1982, the sport had retreated to urban parks and university campuses. A dying version of the game limped along indoors in an ill-supported league, finally expiring in the early-'90s, but few took the sport particularly seriously.

That's not to say soccer didn't exist in America – it's just that many Americans didn't notice it. Soccer does have a long history in the US: American football was directly derived from it, and in the original colonies, the game laid down long roots that run the length of the Atlantic seaboard. Nor was the game hidden. On any given weekend, you could see people playing games in organised leagues with ethnic roots – in parks in virtually every major city.

But the media paid little attention to it. The people playing soccer spoke with funny accents, often weren't white, and were thought (wrongly, as it turned out) the kind of folks who showed up to see other professional sporting events. The media's attitude was infamously summed up by the New York Daily News' Dick Young: Soccer is for 'Commie pansies'.

"The misconception was that there was no soccer here," says Andres Cantor, the broadcaster who made his name during the 1994 World Cup with his now famous "Goool!" call. "There were only a handful of reporters with me in Italy [in 1990], but people forget Hispanic television had been showing games each week since 1987. So why did people act surprised when 70,000 people showed up to see the cup?"

Just as there was no professional league, there was really no national team. Yes, the USA had shocked England back in 1950, but hadn't appeared in a finals again until 1990, after the US were named hosts for '94. Largely stocked by amateurs and college kids, the national team wasn't even close to being globally competitive.

"We never thought we'd play in one World Cup," says former USA defender Marcelo Balboa. "We had no clue what we were getting into. To see two or three reporters at a game? That was two or three more than we usually had."

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Getting the house in order

It was understandably difficult for many nations to wrap their heads around the idea that a country that wasn't playing at a top level could actually host the world's biggest sporting event. "Even we had doubts about fielding a team," says LeTellier. "But to suggest that a country that sent a guy to the moon couldn't pull off a World Cup was absurd. Yet many equated the level of our team with that of our organisation, and it drove some people berserk."

Why the US bid for the World Cup was a no-brainer for the men inside: they had the stadia, the sporting infrastructure, and most importantly, the immigrant population guaranteeing large crowds at every game. In fact, after the successful 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, the US made what the participants describe as an ill-thought out bid for the 1986 World Cup.

"We didn't show a lot of understanding of the basics – we submitted photos to FIFA of the stadiums covered with gridiron lines, and full of ads," says LeTellier. "It wasn't a great bid, and only the Olympic success that helped us to go back."

"There was no logical reason for us to get it in 1986," says Chuck Blazer, the former general secretary of CONCACAF, but then a member of the US Soccer Federation (USSF). "We needed to be much more professional."

Blazer and then-USSF president Werner Fricker made the next move, hiring longtime K-Street lobbying firm Eddie Mahe to shape the politics behind the bid. "We didn't have a wealth of assets," says Blazer. "We had no money, either. They allowed us to run up a half million credit."

And any money they did have soon ran out. "Werner went to his local bank, this little savings-and-loan in Pennsylvania, to put up $750,000," says LeTellier. "And that was great, but the bid cost us $1.5 million. But Werner said there should be no problem, the bank would cover us. So, I pulled the plug on my law practice to join up, and the day I'm supposed to come on board, Werner calls me and tells me the bank had been raided by the Feds, and not only are they not giving us a loan, they're calling the old one in. It was a disaster."

Fricker, who passed away in 2001, tried to bridge the gap by enlisting Patrick Nally, of West-Nally. His solution was to broker a deal with NBC and provide a $1m line of credit from Midland Bank in the UK. One problem was that Nally was disliked by FIFA. Another was that FIFA wouldn't sign off on a TV deal they weren't party to. The biggie, according to LeTellier, were the terms of this loan: "It would have rendered us responsible for all the costs, with him [Nally] getting all the revenue. He would have made $60-70m."

So LeTellier mortgaged his house. "I started using this equity line, and they must have thought I was into drugs, because in four months, I was over $100,000 in the hole. I was paying everything for the bid, including my own salary, from this loan."

What saved the tournament was a Hail Mary pass from an American football player. Heisman trophy-winner Dick Kazmaier worked for Manufacturers Hanover in New York and personally guaranteed an $8m line of credit to the bid committee. "Kazmaier's boss, John McGillicuddy, only gave us the loan because Kazmaier said he would be good for it," says LeTellier. "It was just in time, because my loan was tapped out." But the problems didn't end there.

"Shortly before 1990, I got a call from FIFA," says Alan Rothenberg. "They were very upset about the lack of progress, and told me they were seriously considering moving the cup elsewhere. They asked me if I would take it over and organise it, and I said: 'Sure. How?' They told me that I had to become president of US Soccer. I wasn't even a member."

What Rothenberg was, though, was trusted by FIFA. He had successfully helped steer the sport at the '84 Olympics, had built up a close relationship with Sepp Blatter and had the professional experience that many in the Federation lacked. FIFA were very unhappy with Werner Fricker, who was alienating many of those in the international community, as well as some at home.

"He was being attacked by everyone," says Rothenberg. "If the news wasn't positive, he went nuts. He just couldn't understand the media," adds LeTellier. "Then Paul Breitner, the former Germany player, was quoted as saying our bid was going to be given up, because we had all these financial problems. It became a feeding frenzy, and Werner just fuelled it by being belligerent. Then FIFA found out he was talking to Nally, and they were outraged."

After a blistering campaign, Rothenberg won election to US Soccer's presidency, but inside the organisation, people were worried because they simply didn't know him. "It was distrust, because I was an outsider," admits Rothenberg. "But I also had no idea what the status of the outfit or the management was. Then I found out the organisation was bankrupt, and I wondered what I'd gotten myself into."

Rothenberg made some changes, but retained much of the core staff. And with FIFA's help, they got another lifeline. "We got a line from the Swiss bank that was FIFA's bank, and I don't know whether it was a wink and a nod, but that gave us the cash flow. Then we had that first ticket sale, and it was a huge success. That started to create the sense that this was a hot ticket and that it was sustainable."

Coverage, charges and changes

The Americans still had a major problem – the country is huge, and the venues spread out. Here, those roots of American soccer played a critical role. Turning on its head the old joke that Americans play soccer so they can avoid watching it, USA 94 was staffed largely by volunteer soccer enthusiasts, keeping costs down and maximising profits while ensuring that the core fans of the sport were able to take an active role.

On top of that, the Americans had to convince the stadiums to take a chance on an event few US sports executives knew much about. LeTellier, who was charged with scouting for the arenas, laughs now at the deals he was able to cut. "We did a flat-rate rental," says LeTellier. "We had no idea what the crowds were going to be, and they didn't have any confidence. They would have been better to take the points, but they all had the same doubts we had."

There were still things to be done, including selling it to a suspicious media at home and abroad. US Soccer worked feverishly to convince FIFA that fundamental changes had to be made in the way that teams and players interacted with journalists.

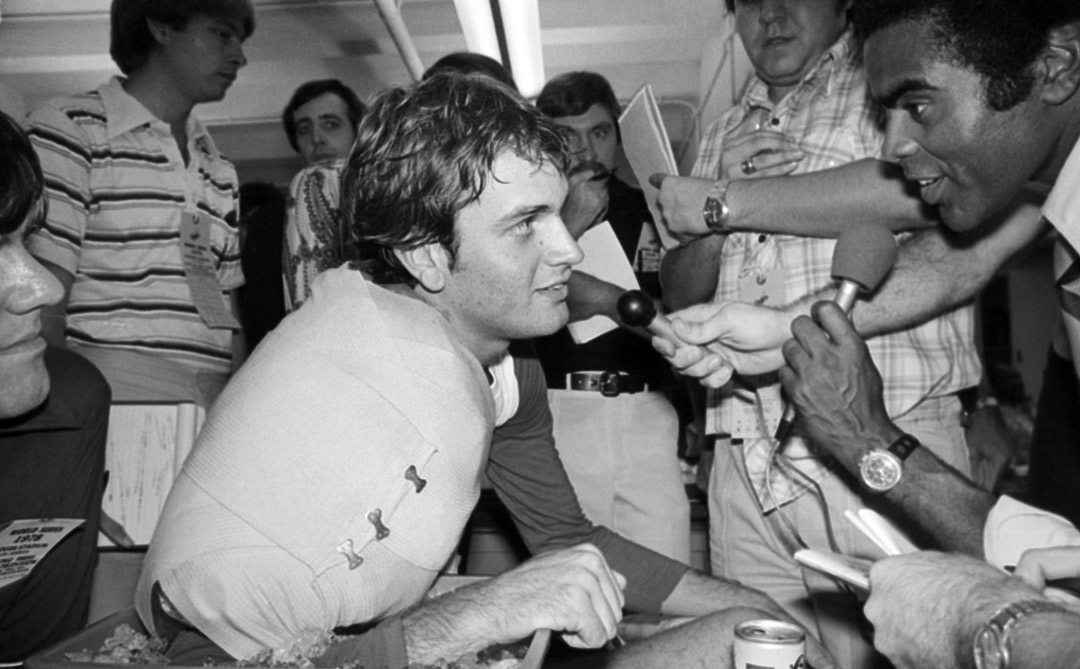

American sports have had a long tradition of close interaction with the media, allowing open locker rooms and mandating interview times for even the biggest stars. Soccer, in contrast, had always jealously guarded the 'sanctity of the dressing room', and many coaches and players had an antagonistic relationship with the media. That approach wasn't going to fly in a country where even Michael Jordan spoke before and after games, so FIFA were pressed to open training and stage press conferences.

Ironically, the American media were the last to realise just what they were covering. Incredibly, the rights-holding broadcasters ESPN didn't plan to air all the games live until a week before kick-off, and only after members of their staff pointed out they would be giving away viewers to Spanish-language TV. (Part of this reluctance might be explained by the fact that the games were scheduled not for American consumption, but for European prime-time, leading to some steamy mid-afternoon matches.)

But one thing ESPN did do right was air the games commercial-free, a radical move in a country whose sports have always been subsidised. To get around this, ESPN borrowed a tactic that has been incorrectly attributed to Fox's NFL coverage – stationing a clock and the score, with a sponsor's name, in the top left-hand corner. (In fact, Hispanic TV had debuted this.) It proved to be a game changer.

Another change that the Americans insisted upon was getting rid of yellow card accumulation in the first rounds in order to keep the stars available – a suggestion made by an American sportswriter who had seen Poland's Zbiginew Boniek suspended for the semi-final in the 1986 World Cup.

But the biggest change came in actually scheduling the matches: the USA convinced FIFA to let the seeded teams move around. "At past World Cups, you essentially had tiers of stadiums, because the big teams didn't move," noted LeTellier. "At the Olympics, we used a mix, and charged a lot – and were getting some astronomical crowds."

One piece the Americans couldn't control, however, was their woeful national team. That, and OJ Simpson, whose trial stole large television audiences.

Meanwhile, on the pitch...

The Americans had stumbled through to Italia 90 with a win against Trinidad and Tobago – a match some suggested had been fixed – and lost all three games at the tournament. "The first game [which the US lost 5-1 to Czechoslovakia], we had no idea what to expect," says defender Balboa. "It showed, and we got our ass handed to us."

This would be unacceptable for '94, and Rothenberg knew it. So the US hired Serb svengali Bora Milutinovic, who had handled Mexico as 1986 hosts, so knew what he was getting into. Slate wiped clean, Bora isolated the team at a training camp in Mission Viejo, CA, where they'd stay for nearly two years.

"I was in Europe, and I would talk to the guys in residency – they were going nuts," says star striker Eric Wynalda. "Too many games, too many practices, too many mental games... they were spent. Some of them were losing it."

"Bora had us playing between 20 and 40 games a year," says Balboa. "But we were also pretty isolated. None of us realised what was going on until after the cup was over and we went to Disneyland, and guards had to come through and escort us because we were mobbed."

"We were essentially famous ping-pong players," says Wynalda. "Alexi [Lalas], Celo [Balboa], Tony [Meola] and Cobi [Jones] got a lot of attention with their funny hair. But no one thought we could hack it. There were a lot of question marks, but Bora deserves a lot of credit, because he had people ready."

Some of that was on display in 1993, when the Americans stunned everyone by making the final of the CONCACAF Gold Cup. In fact, that performance – and the crowds the competition drew – were directly responsible for the formation of MLS three years later.

"FIFA was upset that the pro league we'd promised hadn't been started," recalls Rothenberg. "But as soon as I saw the mess at USSF, I told them we have to wait until after the World Cup, and we hoped that the enthusiasm would give us the momentum. The success in 1993 gave me a chance to bring in two or three guys to build the business plan, and then we were able to use World Cup money to fund the start of MLS.

"Given the faltering of pro soccer in the past, if we'd stumbled, we'd have been dead. We had to have the best funding and the best players we could get, and frankly we had to lower expectations as well. There's a big difference between a cool Wednesday night game in a league and a World Cup, but on the heels of selling out all these games, if we started a league that drew 12,000 a match, people would claim it was unsuccessful."

Still, the Americans' performance was hardly a given. In the run-up to the World Cup's kick-off, the USA struggled, losing to Iceland, Sweden and Romania. But, in a harbinger of things to come, the USA beat Mexico 1-0 on June 4 – the first win against their border rivals since 1991.

The USA opened against Switzerland at the Pontiac Silverdome, an indoor arena. Temperatures on the field were over 100º. Wynalda scored the biggest goal of his career, leading the Americans to a 1-1 draw. "I don't think I'd ever cried during the national anthem," he said. "I wasn't crying out of fear – they were tears of enjoyment. It was just electric there."

"I lost my voice calling that game," recalls broadcaster Cantor. "Waldo's [Wynalda's] goal, that was one of the most meaningful moments of the entire cup for me."

Only one more goal would be scored by an American at the 1994 World Cup, but thanks to a fateful own goal from Andres Escobar of Colombia that gave the hosts a 2-1 win, the USA were able to get out of the group stage. "Thank God," says Wynalda.

"We knew it was going to be the one shot we had to promote it here," explains Balboa. "Nobody knew what it was, but slowly, all of America started talking about it and we started seeing ourselves on the news. The only thing that killed us was the OJ Simpson thing."

After the party

After USA 94, multi-million-dollar bonuses went to the Americans who had made the event possible. And why not? The successful tournament changed the economics of the World Cup, turning it from a million-dollar event into a multi-billion-dollar one. It also turned what some had naively seen as a quaint sporting event into a major sports business.

In the States, the effects were just as lasting. Today, more soccer is available on TV to American viewers than in any other country on the planet, with four full-time cable channels devoted to the world game. MLS has finished its 19th season, and is undergoing the growth (and growing pains) that come with success. The national team have qualified for seven straight World Cups, and go to Brazil as equals. Hundreds of Americans now play professionally in Europe, Latin America and the USA.

"Where would we be without it?" asks Balboa of '94. "We'd probably have no league, no one then would have given an American a chance. Now we have guys everywhere, and most of them were inspired by '94. That's a huge legacy. It really made the sport."