Action Replay: 'Clown' Tomaszewski helps Poland's 'donkeys' deny England

Dominic O'Reilly recalls the ultimate upset.

If Poland qualify for the World Cup, “it cannot be pretended that they would be anything other than remote outsiders,” wrote Brian Glanville in the matchday programme (price 10p) on Wednesday 17 October 1973.

“England, almost ex officio, would be among the favourites, the old warhorse, eternally responding to the trumpets. As they doubtless will, tonight.”

Glanville’s views echoed those of a nation. As England prepared for their World Cup qualification showdown with Poland, Alf Ramsey’s side were universally expected to ease their way into the following year’s finals in West Germany.

No matter that for England it was win or bust, while Poland, at the top of the group going into this final match, needed just a draw. These were the days when qualifying for major tournaments was a formality for the English. The 1966 and 1970 World Cup sides were fresh in the memory and, though a young Poland side had shown promise by winning Olympic gold in Munich the previous year, no one seriously thought these unheralded Slavs from behind the Iron Curtain could stop England.

15.11.72 Wales 0-1 England

24.01.73 England 1-1 Wales

28.03.73 Wales 2-0 Poland

06.06.73 Poland 2-0 England

26.09.73 Poland 3-0 Wales

17.10.73 England 1-1 Poland

Even when England suffered their first ever World Cup qualifying defeat in a brutal match in Chorzow with Alan Ball sent off, no one in England was too concerned. When the Poles used the same roughhouse tactics to beat Wales and top the group, it was still assumed that their limitations would be exposed at Wembley, particularly when Ramsey’s side thrashed Austria 7-0 in a warm-up friendly.

“There was such confidence in the camp,” recalls England and Leeds defender Norman Hunter. “Alf said that the reports he’d had of the Poles were that they weren’t the best of sides – if we did our best we would get the win we needed.”

Striker Allan Clarke expected the Poles to be overawed by a capacity crowd of 100,000 on their first appearance at Wembley. “Not many countries liked coming to Wembley back then,” says the then Leeds United striker.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

“By the time Wembley closed all sorts of teams had won there, but it was different back then. And Alf’s attitude was always, ‘Let them worry about us.’ He knew that you don’t need coaching at international level and that tactics don’t win matches, individuals do.”

And when it came to individuals, England believed they were superior. “There was so much talent around you could have selected two or three England sides and there would have been nothing between them,” says Manchester City’s England midfielder Colin Bell. “We were lucky to follow the lads who’d won the World Cup too. That gave us a lot of confidence.”

The world in 1973

Perhaps England should have looked at what was happening in the world around them, for the game took place against a backdrop of global crisis and the emergence of a new world order. As the Yom Kippur War raged in the Middle East, the oil price rocketed as the Arab-dominated OPEC announced an embargo against the US and other nations that provided military aid to Israel. Economic power now lay in the Persian Gulf.

A ceasefire held in Vietnam, but US vice-president Spiro Agnew had just resigned and Richard Nixon would soon follow. Britain had finally joined what was then called the European Economic Community under PM Ted Heath, but the Tories would lose power the following year.

Soundtracking these events, Pink Floyd released Dark Side Of The Moon and Elton John came up with Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, while Martin Scorsese, Robert De Niro and Harvey Keitel made their names with Mean Streets and Bruce Lee’s Enter the Dragon inspired kung fu kicks in playgrounds across the world. Roger Moore stopped being a Saint and became James Bond and a British institution was born as the Wombles made their first appearance on our screens.

Not even football could stand still. The Dutch had created total football, with players free to roam over the pitch, and the Poles would soon play their part in upsetting the old powers and assumptions. Unheralded they may have been, but despite missing their main striker, the powerful and aggressive Wlodja Lubanski, Poland had plenty of talent. There was Grzegorz Lato, whose thinning hair made him look older than 23, nippy winger Robert Gadocha and midfield maestro Kazimierz Deyna, who would play for Manchester City before dying in a car crash in the USA aged 42.

A week before they lined up at Wembley, the Poles had the better of a friendly draw with Holland in Rotterdam. England, according to Lato, had been warned.

“A Dutch player told the English team that we were dangerous. We say in Poland, ‘Don’t try to skin a live bear’, meaning don’t take something for granted, but England did. Mind you, even our press were saying 5-0 to England.”

In England, Poland were dismissed as no-hopers. With their old-fashioned haircuts and little moustaches the Poles were ripe for teasing in a country where David Bowie had just toured as Aladdin Sane, Slade and Gary Glitter had married pantomime to glam rock and, whether in Afros, sideburns or platform heels, the fashion was for excess.

The crowd whistled during our anthem; they kept shouting ‘animals’ and threw cans. It was not what I’d expected from a civilised country"

Among the Poles only centre-half Jerzy Gorgon, with his tumbling gold locks, looked the part. As for the rest: “The English press ran our photos and said, ‘He looks like a murderer, he looks like a clown’,” recalls defender Leslaw Cmikiewicz. “The crowd whistled during our anthem; they kept shouting ‘animals’ and threw cans. It was not what I’d expected from a civilised country.”

Playing to the gallery in the TV build-up to the match, Brian Clough labelled Polish goalkeeper Jan Tomaszewski “a clown”, advising ITV viewers to settle down and enjoy an English victory. His sidekick Peter Taylor joined in by calling the Poles “donkeys”. But English arrogance was to come back to haunt them. “Clough trod on my honour,” says Tomaszewski. “But what he said gave me extra verve and energy.”

If Tomaszewski was annoyed by the insults, however, his first concern was with avoiding humiliation. “Walking onto the pitch at Wembley, I had legs of jelly. I was thinking, please don’t let it be another 7-0. I didn’t want to be remembered for letting in lots of goals at Wembley. I would gladly have lost 10 years of my life to get a draw because we felt it was a 100-1 chance, maybe 1000-1.”

As the teams were introduced to FIFA president Sir Stanley Rous, England’s self-assurance frayed Polish nerves. “The Poles looked terrified of us,” recalls Allan Clarke.

“We stood to attention. We’d only played maybe 15 internationals and were still learning,” adds Tomaszewski. “England were so relaxed, chewing gum and looking like they thought they would get three in the first half and then play around.”

Entertained in the build-up by the bands of the Grenadier Guards and Scots Guards, who played an eclectic collection of tunes including a few West End show numbers and the best of The Seekers, England’s fans now cleared their throats.

For Jan Tomaszewski, it was an unforgettable moment. “I never again heard noise like the roar when they started the anthem. I tried to say something and couldn’t hear my own voice. England played with 12 men at Wembley because of the crowd.”

Adrenaline takes over

It was a mild autumn evening, the pitch was in good condition and the touchlines had been pushed back to give England extra room to break down a Polish team who were expected to pack the defence. England fielded the same side that had hammered the Austrians, with Clarke, Martin Chivers (Spurs) and Mick Channon (Southampton) up front, and Bell, Tony Currie (Sheffield United) and Martin Peters (Spurs) providing attacking options in midfield.

Poland knew what to expect. “The manager said there would be an onslaught,” says Tomaszewski. “He told us to slow it down and last as long as possible.”

In the third minute, the plan almost went out of the window. “I dropped the ball in the area and because of the noise of the crowd, I didn’t realise Clarke was advancing,” explains Tomaszewski. “Just in time I dived on the ball and got kicked in the hand. There was no malice, it was a fair challenge but it woke me up. Without it I would have carried on in a daze and who knows what could have happened.”

In fact, Clarke’s challenge had broken a bone in Tomaszewski’s hand. “The physio used pain-killing spray and I got on with it. Adrenaline took over and for the rest of the game, I didn’t feel a thing.”

The noise was causing havoc, though, preventing the Poles from communicating with each other. “Everyone had to rely on instinct and memory,” recalls Tomaszewski, “but it meant we could forget tactics and play with freedom. We gave ourselves over to spontaneity so it was like musicians making up some jazz rather than playing a symphony.”

Tomaszewski, his huge frame conspicuous in a bright yellow jersey, was like a footballing Charlie Parker, his performance an inspiration to his team-mates. “Jan was so brave and confident,” says Grzegorz Lato. “He was coming for crosses even 15 metres out. Anything he could reach he saved, anything he couldn’t, we kicked away.”

Everyone had to rely on instinct and memory, but it meant we could forget tactics and play with freedom"

But the Poles were having to soak up a lot of pressure, struggling even to escape their own penalty area. “We wanted to keep possession but England would not let up,” says Tomaszewski. “Every time we got the ball the crowd was silent, which was eerie, but England would soon get it back again.”

Not that it was easy for England to attack. “It’s hard enough trying to break down a team when they get everyone behind the ball,” says Colin Bell, “but they had 11 men in the box for much of the time.”

When the half-time whistle blew, the exhausted Poles traipsed back to the dressing room for some respite. “There’s no point lying, at half-time we were hanging on,” says Leslaw Cmikiewicz. “We knew it was desperate.”

But while the score was 0-0, Poland had hope. “The coach said, ‘Another 45 minutes and you’re in the World Cup finals’, and that filled us with spirit and determination,” says Lato. “He said every minute that went by would increase the pressure on England and we should take advantage.”

As the military bands entertained the crowd once more, though, no one was panicking in the home dressing room. “Alf just said, ‘More of the same and you’ll come out on top’,” says Hunter. “We agreed because we’d never seen such a one-sided game. It was world-class goalkeeping, but we were battering them with wave after wave of attacks.”

Suddenly, at the other end...

The second half began as the first had ended, with Poland camped deep inside their half. But with 57 minutes gone, Henryk Kasperczak broke out to find Lato with a pass. Hunter went for a block tackle on the halfway line, anxious to get the ball back upfield quickly, but to his astonishment, Lato skipped deftly past him. “I should have put him and the ball in the Royal Box,” laments Hunter. “But even then he had Peter Shilton to beat.”

Seizing the moment, however, Lato slid the ball to striker Jan Domarski, who had been waiting for his opportunity all night. “I was 15 metres out when the ball came,” he recalls. “The pass was quick so although the defenders were closing in I could hit it early, almost on the volley.”

I should have blocked it with my legs or stopped it with my hands but I did neither and the pace beat me"

Shilton, a spectator for much of the game, reacted slowly, and as the home fans watched in horror, the ball squirmed under his body and into the net. “I should have blocked it with my legs or stopped it with my hands but I did neither and the pace beat me,” he recalls. The goal was greeted by deafening silence. All of a sudden, the World Cup finals felt a very long way from England.

Six minutes later, the roar returned to the throats of the England fans when Martin Peters was adjudged to have been pushed over by Musial after intercepting a sloppy back pass by Domarski. The referee awarded what was seen at the time as a softish penalty.

Allan Clarke stepped up to the spot. After 21 unsuccessful attempts on the Polish goal, though, some England players were beginning to think this wasn’t their night. “I didn’t think we were going to score,” says Colin Bell, “and I remember Martin Chivers turned his back on it.”

As two nations held their breath, the calmest man was Clarke. “I’d always watch goalies in the warm-up and see if they were right or left-handed,” he explains, “so I knew where to put it.”

Tomaszewski, who would become the first man to save two penalties at a World Cup finals, remains impressed. “One down at Wembley and he was as unemotional as a statue, as if it was a training session. I dived right and he put it left. Or, as we say in Poland, he sent me to fetch the beer.”

England now had 27 minutes to secure victory and their place at the World Cup. “The crowd went crazy and the England attacking was just constant,” says Tomaszewski. “I was almost in a trance, I had no time to think or worry. I was in what people call 'the zone'.”

As England piled forward in search of that all-important goal, even Hunter had a couple of shots, but they were leaving themselves exposed. “From the halfway line I had a good opening but I thought I was offside and hesitated,” recalls Lato. “Then I was through for a one-on-one with Shilton but [Roy] McFarland pulled me back. Still, better he did that than kick me brutally.”

"I thought, 'It ain't gonna be'"

For the Poles, clinging on, time seemed to stand still. For England, it was advancing rapidly, but Allan Clarke was convinced the winner was coming. In the dying minutes the Leeds man thought he had scored it with a volley from just a few yards, but somehow Tomaszewski pulled off his finest save of the night.

“I couldn’t even see their keeper, there were so many bodies,” says Clarke. “I remember thinking, that’s it, hitting the top corner, you little beauty. I’d half-turned to celebrate when I saw this yellow arm appear. He can’t have seen it, he must have put up his arm instinctively. As the ball dropped, it was kicked clear and that’s when I thought, 'It ain’t gonna be'.”

Tomaszewski admits he doesn’t know how he kept Clarke’s shot out. “I don’t know whether God told me what to do or if it was luck,” he chuckles. “But I knew then that they would not score again. The two saves from Clarke, at the start and finish of the match, were my crucial moments.”

I’d half-turned to celebrate when I saw this yellow arm appear. He can’t have seen it, he must have put up his arm instinctively"

There was still one last chance, though. With five minutes left, Ramsey, who said afterwards that his watch had stopped, finally sent on Kevin Hector for Martin Chivers. The Derby forward was almost an instant hero. “He hit a player on the goal line with a header from a corner,” recalls Hunter. “It might have been his first touch. But that was the story of the night, world-class goalkeeping by them and no luck for us.”

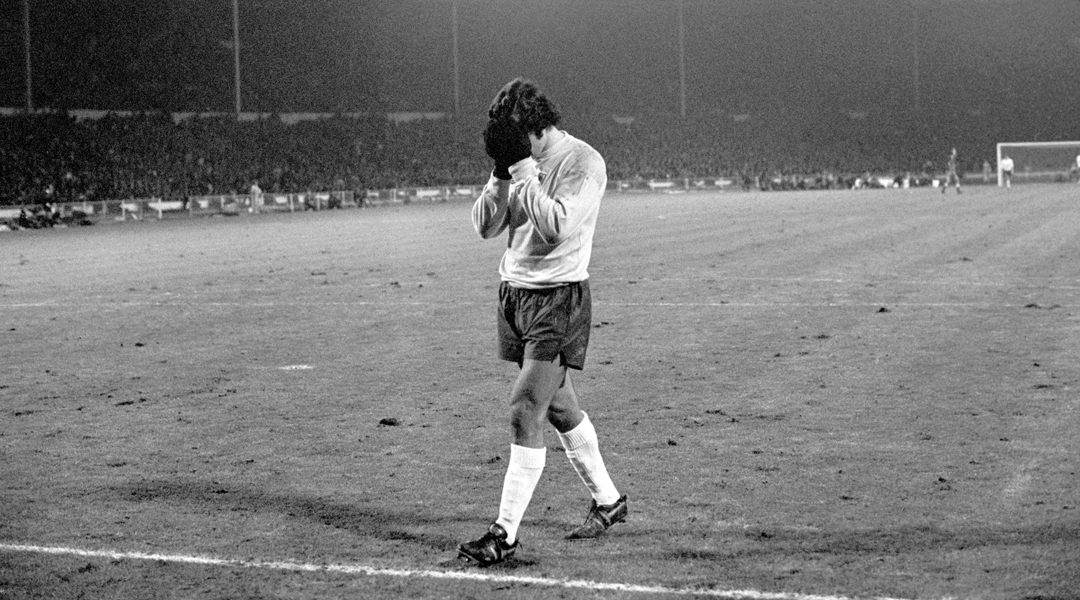

The whistle went soon after and the English players staggered disconsolately off the pitch. “Bobby Moore put his arm round my shoulder and said something, but to this day I don’t know what it was,” says Hunter. “I wasn’t able to take anything in. The dressing room was silent, we all knew we’d blown it.”

Ramsay’s first thought was to console his players. “Alf said, ‘I feel very sorry for all of you, you couldn’t have given any more or played any better, I suppose we were fated not to win the match’,” Clarke recalls.

The Poles went to a disco to celebrate and there they realised just how much they had shocked the English. “The DJ spotted us and kept playing songs from 1966,” says Cmikiewicz. “We ended up feeling sorry for the English supporters because some of them were in tears.”

'The end of the world'

The following day, the team returned to Poland and a reception that still astounds them. “Normally crowds and celebrating were orchestrated by the communists, but it happened everywhere we went,” says Tomaszewski, “and even now children still know our names by heart. Money comes and goes, the same with fame, but what we experienced and the effect it had on our people is priceless.”

Meanwhile, English football was plunged into despair: one newspaper described it as ‘the end of the world’. The players were devastated. “It sticks in my throat,” says Colin Bell. “If we’d replayed that game, we’d have played the same way and scored six. After a defeat at club level it would take me two or three days to get back in the swing, but it took three months to get over the Poland game. I was at the height of my international career, looking forward to the World Cup and that all fell apart in one game.”

Shilton, whose mistake proved decisive, still feels upset. “As a young player, I knew I had another chance but it didn’t matter. Even though I played in three World Cups, it never took away that disappointment.”

Clarke recalls a strange reaction when he returned to Leeds United. “Even the Jocks didn’t tease us when we got back, and that’s saying something. They knew we’d been so unlucky it was beyond a joke.”

Today in England, the result is still usually attributed to Tomaszewski’s inspired performance and dismissed as a one-off, but that analysis ignores what happened to the two sides over the next decade. The delirious Poles had come of age. “The ugly duckling became a swan,” says Tomaszewski. “We suddenly thought, we can do this, and from then on we would always take strength from that moment. Anyone bold enough to survive the ordeal of Wembley – fans, atmosphere and expectation – can survive anything. How did the pressure of the World Cup semi-final compare to Wembley? Like driving a Skoda after a Mercedes.”

Tomaszewski was later offered the chance to replace Pat Jennings at Spurs but Poland’s communist regime refused to let him go. The Poles, though, would go on to light up the World Cup where, in the absence of Lubanski, they put their trust in the pace of Lato and Gadocha and deservedly beat Italy and Argentina to top their group.

How did the pressure of the World Cup semi-final compare to Wembley? Like driving a Skoda after a Mercedes"

In the second round group where the winners reached the final, they defeated Sweden and Yugoslavia before losing to the West Germans on a sodden pitch in what was effectively a semi-final. Beating Brazil in the third place play-off was some consolation, however, and the Poles would also qualify for the World Cups of 1978, ’82 and ’86, finishing third again in 1982.

In contrast, in England the recriminations began. Shock turned to outrage and Ramsey was made the scapegoat, dismissed after 11 years in charge, to the disgust of his players. “The saddest thing was that we sacked the best manager we have ever had,” says Hunter. “It was diabolical after what he had achieved and I think we’d have done well if we’d qualified for the World Cup.”

But for England, failure became a habit. As the team stagnated under Don Revie, they would not qualify for another major tournament until the European Championship in 1980. Qualification, until then a formality, was suddenly an ordeal. Even now, English football has still not banished the ghost of Jan Tomaszewski. In that time, England have knocked Poland out of four World Cups and two European Championships but still the national side are haunted by that 1973 failure.

Fans and players who weren’t even born when Tomaszewski and his team-mates shattered England’s dreams, today view every qualification hurdle as ‘a potential Poland’. Not bad for a clown leading a herd of donkeys.