Alfredo Di Stefano: Icon

The greatest legend in Real Madrid's history...

Countless footballers have earned winner’s medals, a place in the hearts of fans or their 15 minutes of fame. Some have produced moments of magic that linger forever in the minds of those fortunate enough to witness them or carried entire teams to glory, clinching immortality.

But few can truly claim to have changed history. And none can claim to have changed history quite like ‘The Blond Arrow’, Alfredo Di Stefano – a pioneer, artist, wit and winner, the most important player of all time.

Di Stefano jokes that he only became a footballer by chance. “One day,” he explains, “an electrician came to our house. He played for River Plate and he got chatting to my Mum. She told him I played a bit of football, so he took me for a trial. When I got there, I was asked who introduced me and I replied: ‘My Mum’.” It was a chance encounter that changed the game. As UEFA president Michel Platini puts it: “The history of football simply cannot be imagined without Don Alfredo’s extraordinary presence.”

"Better than Pele"

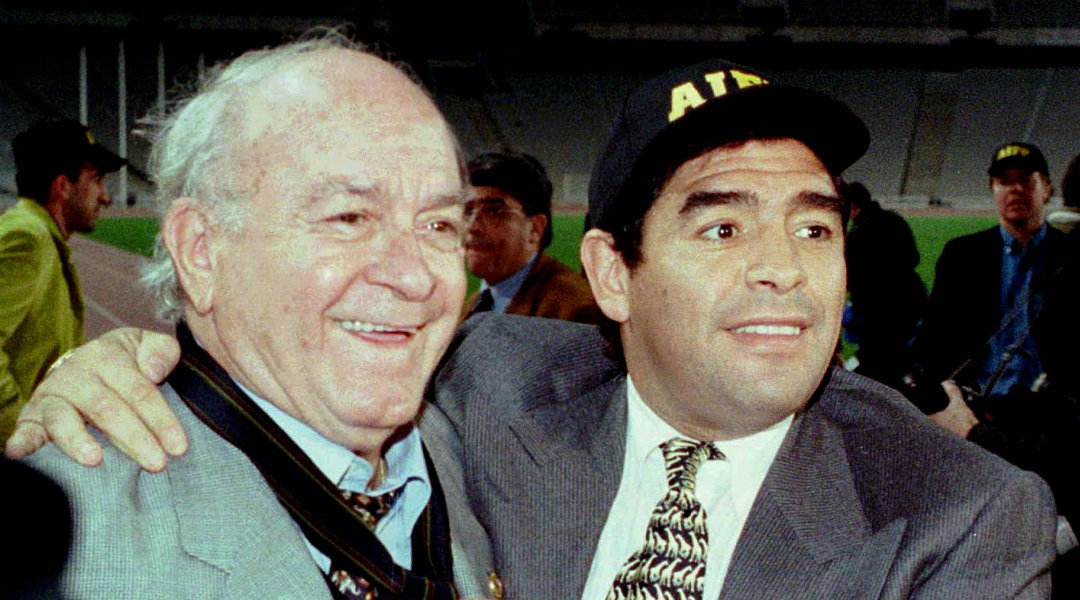

Diego Maradona may have taken tiny, tradition-free Napoli to an unthinkable Scudetto and Argentina to an improbable World Cup but, when it comes to a lasting legacy, that barely registers against the impact of the man who was born in Buenos Aires 60 years before the hand and feet of God defeated England. Di Stefano is the only man Maradona ever rated more highly than himself; the man who altered the face of football forever.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

When FIFA came to name the 20th century’s best player, they couldn’t decide between Pele and Maradona. Few could. Not even Maradona, who remarked: “I really don’t know if I was better than Pele.” What Maradona did know, though, was that “Di Stefano was better than Pele”. “The mere mention of Don Alfredo,” he insisted, “fills me with pride.”

The legendary Inter Milan and Barcelona coach Helenio Herrera agreed. “If Pele was the lead violinist,” he once said, “Di Stefano was the entire orchestra.”

Birthdate 4 July 1926

Birthplace Buenos Aires, Argentina

Height 5ft 10in

Position Forward

And yet Di Stefano – denied the opportunity to exhibit his talent at the World Cup despite playing for three different countries, and having performed his magic in an age before mass television ownership, not to mention a country only just emerging from political and social isolation – has rarely been afforded the status handed to those two universally accepted greats.

His finest and most renowned moment came in the 1960 European Cup Final, when Real Madrid defeated Eintracht Frankfurt 7-3 at Hampden Park – a match the BBC in Scotland continued to show every Christmas for years; the only one that continues to sell, still in black and white, on DVD. A game in which, according to one report, Madrid “played like angels” in front of the highest-ever attendance for a European Cup final: just the 127,000.

It was a performance that the Guardian journalist Richard Williams described as “Fonteyn and Nureyv, Bob Dylan at the Albert Hall, the first night of the Rite of Spring, Olivier at his peak, the Armoury Show and the Sydney Opera House all rolled into one”.

Sir Alex Ferguson, watching from the stands, still remembers it as the finest game he ever saw; one in which, according to another paper the following morning, “Real flaunted all that has made them incomparable.” “To list Real Madrid’s team,” added this scribe, “is to chronicle greatness.” And the greatest of them all, the undisputed leader of the side, was Di Stefano – “a great amongst greats”, says Platini.

But while such sublime football, unfolded in front of a Scottish audience, thrust Di Stefano into British consciences, he would soon largely disappear from most minds, that game proving a fleeting vision of perfection.

CLUB

1943-49 River Plate 65 (49 goals)

1946-47 Huracan (loan) 25 (10)

1949-53 Millonarios 102 (88)

1953-4 Real Madrid 510 (418)

1964-66 Espanyol 47 (11)

INTERNATIONAL

1947 Argentina 6 (6 goals)

1949 Colombia 4

1957–61 Spain 31 (23)

In England, Maradona and Pele are followed by Best or Charlton; in France, by Platini or Zidane; in Holland, by Cruyff; in Brazil, by Garrincha; in Germany by Beckenbauer; across the world, by a combination of them all. In Spain, where he played, it’s not that Di Stefano follows Pele and Maradona, it’s that he matches them. Exceeds them, even. Joaquin Peiro, the Spanish midfielder who played in the great Inter Milan team that won the European Cup in the mid-’60s, speaks for many in Spain when he says, “For me, the No.1 is Di Stefano.”

Those that saw him often, knew. Those that didn’t, missed out. Sadly there are many of them. In 1950 and 1954, his native Argentina did not go to the World Cup, in 1958 his adopted Spain did not qualify and in 1962 a muscle injury prevented him from travelling. His absence is one of the tragedies of the game. “If Di Stefano had played at the World Cup”, says Just Fontaine, “he would be recognised as the white Pele.”

Destroying orthodoxy

With that gruff, impenetrable accent, punctuated with Argentinian slang and the wisecracks that characterised him, Di Stefano insisted: “For me, it was always about the team.”

If FIFA struggled to decide between Maradona and Pele, there was no doubt when it came to naming the century’s best club. Having recently been named the club’s honorary president, Di Stefano collected the award on behalf of Real Madrid.

It was fitting that his award was about the team, about more than just one man – “he was my favourite player,” recalls Cruyff, “and what I most loved about Di Stefano was everything he did he did for the team.” Less fitting was that he should have to hand it over rather than keeping it himself. If anyone made Madrid the world’s most successful club, it is he.

Without Di Stefano, much of modern football does not make sense. Destroying the tactical orthodoxy of the WM formation with his constant movement and awareness, he propelled the game into the modern era. “Di Stefano turned still photographs into the cinema,” says Arrigo Sacchi. When he did an advert for tights, a photograph of him with his wife’s legs splashed across newspapers, it was a first for a footballer. And how many players could claim to have been kidnapped, as Di Stefano was in 1963 in Venezuela? Even if he did later insist with a smile, “they seemed decent enough kids.”

He contributed more than any other player to making the European Cup – then in its infancy – the biggest club competition in the world. Without him, it may never have got off the ground. Without him, Madrid might not have done either. In fact, without Di Stefano, Real Madrid do not make sense; their entire culture, values, and identity is bound up in what he brought to the club. Without Di Stefano there would be no galacticos, no jam-packed Bernabeu, no European dominance. No undisputed status as the world’s greatest club.

Madrid wouldn’t be the most successful club in Spain, their trophy haul dwarfing the rest of the country, Barcelona included. They definitely wouldn’t be the most popular club in Spain and possibly the world. “He made Spain Madridista. And he it was who carried Real Madrid across borders,” insisted former club president Ramón Calderón – and he’s right.

Even the relationship with Barcelona would be different, the Argentinian’s transfer to Madrid not the Catalans in 1953 proving a turning point and the ultimate bone of contention in the globe’s biggest footballing rivalry. His disputed transfer – involving River Plate, Colombian club Millonarios, Barça, Madrid, FIFA, and the Spanish state – still smarts at the Camp Nou.

When it comes to ruing the ones that got away, Barcelona’s failure to secure Di Stefano, who had already played three friendlies for them, must rank as the biggest mistake in footballing history. Or, according to Barcelona, the biggest con.

Don’t hold it against him but without Di Stefano there would be no arrogance, fawning press or pursuit of Cristiano Ronaldo, either. And, definitely don’t hold this against him, but some insist that Spain’s social and political history would have changed too.

After all, one Franco regime official, witnessing Madrid’s marauding European success, described the club as the “greatest embassy we have ever had” at a time of ostracism. Di Stefano stood at its head, the most important ambassador of all.

Football can be divided into a Before Di Stefano and an After Di Stefano. “The history of Madrid starts with him; his arrival was the beginning of Madrid’s legend,” claimed former striker Emilio Butragueno. Six-time European Cup winner Paco Gento insisted Madrid “were lucky to sign Alfredo. Nothing would have been the same without him.”

Luis Suarez, the Barcelona striker who remains the only Spanish-born player ever to be named European Footballer of the Year (the season after Don Alfredo), adds: “Di Stefano turned Real Madrid around and transformed them into a truly great team – Alfredo was the revolution.”

It’s no exaggeration. Di Stefano recalls with a cackle how in Argentina he told a friend that could sell a man a dummy and immediately get away. “But here in Europe,” he grins, “I had to sell 40 dummies”. So he sold 40. Despite the leap, he was an unimaginable success.

When the Blond Arrow joined Real Madrid in 1953, they weren’t a particularly good team. They hadn’t won the league in 20 years. They’d only ever won it twice. Barcelona, Athletic Bilbao, Atletico Madrid (then called Atletico Aviacion), and Valencia had all won more.

From the streets to the peaks

Throughout his later years Di Stefano kept a small medallion in his pocket engraved with “River Plate-San Lorenzo de Almagro, 1947” – the day of his first game back at River after a year on loan at Huracan – the day he singled out as the best moment of his career when FourFourTwo asked him for our 100th edition.

He remained lucid, sparky and funny as ever despite a heart attack in 2005. In later years he was always at his happiest talking of his time playing in Los Cardales, some 40 miles outside Buenos Aires, speaking with fondness of “players from the potreros [the rough streets] who would have made it but had to earn money for their families instead.”

And yet, for all that – and despite two South American Player of the Year Awards – his greatest triumphs came in Europe, where he turned that history on its head, making Real Madrid the biggest club in the world, laying the foundations for the Behemoth that now stands astride the Paseo de la Castellana.

He won eight league titles in 11 seasons; after just two in the years before Di Stefano, Madrid have won 30 since his arrival – more than half of those on offer. More importantly, Madrid won the first five European Cups, setting up a dynasty that remains unchallenged and defines the club: no football team has ever been as synonymous with a trophy as Madrid with the European Cup.

Madrid had other players, of course: Paco Gento and Ferenc Puskas were amongst the finest of their generation. But Di Stefano was the best; it was he who started it off, who led them. “For children of the 1950s, Di Stefano was above all a victorious sound on the radio, his name echoed round like a heartbeat associated with some success or other, transporting us to the Parques des Princes, San Siro or Hampden Park,” recalled the editor of sports daily AS, Alfredo Relaño.

Di Stefano was top scorer in the league five times, finishing his career with 216 in 282 games for Madrid – a figure that makes him the club’s second highest scorer in La Liga, behind Raul. He scored in every one of those five European Cup finals, becoming the competition’s highest ever goalscorer with 49 – a figure only surpassed by the Champions League generation, current captain Raul taking twice as many games. In total he scored 418 goals for Madrid.

More than a forward

And he wasn’t even a striker. Not really, even if he did wear the No.9. Goals alone do not account for two Ballón d’Ors and five Spanish Player of the Year awards. “He had it all,” said Fontaine. “He was quick, technically gifted, good in the air, a goalscorer, an organiser and a respected leader.” “He brought to Europe a tango made of perfect technique and terrifying acceleration,” added Platini. “He totally controlled the game. You looked at him and asked yourself: ‘how can I possibly stop him?’” recalled Bobby Charlton.

The answer, much of the time, was that you couldn’t – and Di Stefano knew it. Ten minutes into one game, he turned to Fidel Ugarte, a young defender, and said: “Are you going to follow me everywhere, sonny?” Nervously, Ugarte replied: “Yes, my coach told me I have to.” “OK,” shrugged Di Stefano, “you might even learn something.”

Calderon recalls listening to the radio and imagining “some kind of superman”. It’s easy to see why. Di Stefano was everywhere. L’Equipe dubbed him ‘L’Omnipresente’. “It’s no exaggeration to say that he played like three players put together,” said one biographer. “He was a midfielder who won the ball and started the play, a No.10 who controlled the game and delivered the final pass, and a striker who put the ball in the net. If you put together Redondo, Zidane and [Brazilian] Ronaldo, you might just get close to what he was.”

“The only thing he didn’t do,” says one former team-mate, “was play in goal.” “Actually,” Di Stefano grins, “I did once – for River when then had their first-choice keeper sent off.”

It's not just Di Stefano’s talent that won him such success and admiration, but his temperament too: his determination and desire to win, even if it meant sacrificing himself. Especially if it meant sacrificing himself. The great Italian Gianni Rivera recalls one occasion when Inter put two players on him. So Di Stefano simply ran around the most pointless areas of the pitch, sprinting about the full-back areas, seemingly running blind, tiring them out and leaving space for his team-mates. “He drove us mad,” Rivera sighed.

“He was the brainiest player I ever saw,” said Charlton, “and he oozed effort and courage. He was an inspiring leader and the perfect example to others.”

“I always saw football as a game in which you have to run and sweat,” Di Stefano said. And he could be sharp with his tongue and fiercely irritable with those who didn’t give their all in pursuit of victory. His quick-fire response to another Madrid great Amancio is the stuff of legend – the embodiment of what Madrid like to think they’re all about: talent and commitment wrapped in one.

Before a match, Amancio noted that his Real Madrid shirt was plain white. “Hey, my shirt has no Real Madrid shield on it,” he announced. “You’ve got to sweat for it first, sunshine,” replied Di Stefano.

Di Stefano certainly sweated for his shirt. Not that Eusebio cared: Portugal’s finest ever player still claims that swapping jerseys with the Blond Arrow was “the greatest satisfaction of my life”. Football will forever be grateful to an electrician from River and a mother’s love.

Ramon Calderon likes to tell the anecdote of a father and son strolling through a park and coming across a statue of Di Stefano. “Daddy,” says the boy, “was he a player?” “No,” says his father, “he was a team.” Not just any team either: the greatest team in history.