Ambition, invasion and a dead parrot: Why Arsenal vs Tottenham is more than a game

Arsenal have been annoying Spurs for years: they’ve moved in on their turf, stolen their captain, imitated their style and even managed to get them relegated. For the May 2006 FourFourTwo magazine, Mat Snow investigated the rivalry – with a little balancing help from a Gooner or two...

Every football club and its supporters like to nurse a sense of injured innocence, a myth of victimhood which can be trotted out to justify any unsporting act on or off the pitch.

For Arsenal, it is Manchester United, the Northern bully using its institutional weight to crush its plucky Cockney rival. For Man United, the capital-M Media is determined to stitch them up every chance it gets. For Liverpool, the whole known universe conspires to do down the red half of self-pity city.

As for Tottenham Hotspur, it is Arsenal, the carpet-bag club which moved in on their manor, tried to siphon off their fans, stole their top-flight status, hijacked their keeper, lured away their captain and, perhaps most gallingly of all, pirated their style.

Arsenal hate Spurs for the usual reason: because they’re there. Spurs hate Arsenal because they shouldn’t be there in the first place

All paranoid nonsense, of course. Except for the last one. Spurs have a case. Where most local rivalries are about no more than that, locality, Spurs’ disdain of Arsenal carries the extra charge of morality.

Arsenal hate Spurs for the usual reason: because they’re there. Spurs hate Arsenal because they shouldn’t be there in the first place.

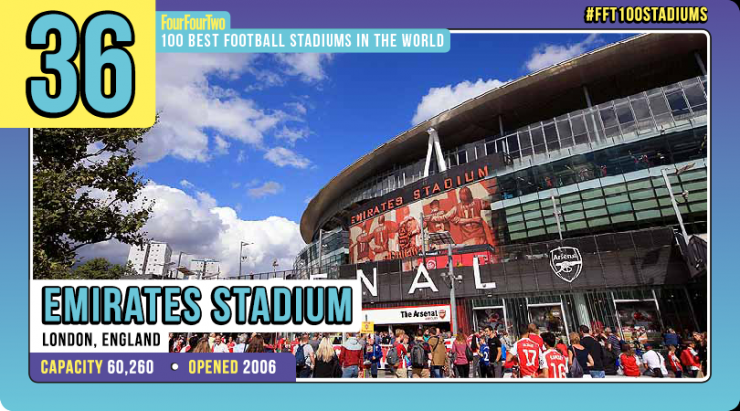

On April 22 2006, a capacity crowd will witness the final encounter between Arsenal and Spurs at Highbury, whereupon the junior club decamps a few hundred yards back in the rough direction of where it was founded, in the bowels of the arms industry south of the Thames in Woolwich.

From dar-as-sina ab, meaning place of manufacture, the very word 'arsenal' is derived from Arabic, so the move to the Emirates Stadium marks a return to the club’s etymological roots too. (As a teenager living in London, Osama Bin Laden followed Arsenal. Fact.)

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

The club which shouldn't be there

In between its flit from the death factory in 1913 and up-market move this summer to a converted rubbish recycling plant handily situated for the King’s Cross red light district, Arsenal have cultivated an air of Establishment pomp.

Just as a fly-by-night finance house will adopt the trappings of pillared and pedimented permanence to camouflage the fact that it’s no better than a clip-joint or casino, so Arsenal marbled its halls and filled its boardroom with blazered Old Etonians.

“Good old Arsenal!” its fans in flat caps would cheer during the club’s era of dominance in the 1930s – aptly known as the Great Depression – but it was good and old in the same way as a Georgian-style executive development is good and old: a thin veneer of sprayed-on class that may fool snobs but not connoisseurs.

For that hugely successful transformation, Arsenal owe everything to bent businessman and Tory MP, Sir Henry Norris. Readers of FourFourTwo will already know something of this hulking crook in bowler hat and pince-nez; an expanded version is to be found in the book Rebels For The Cause: The Alternative History Of Arsenal Football Club, by Jon Spurling, who, being a Gooner, can hardly be accused of anti-Arsenal bias in his interpretation of the facts. (As for yours truly, my sympathies are obvious; But in the finest traditions of FFT, Arsenal’s side of the story will be treated with all the fairness it deserves.)

Norris was a self-made and very well-connected property developer who knew who to lean on, whose wheels to grease and where the bodies were buried. Already a director of Fulham FC, his ambition was to command a London super-club.

Woolwich Arsenal had a mud-heap pitch, a fan-base restricted to an inaccessible corner of Kent, and a load of debt. Like Chelsea nearly a century later with Abramovich, the Woolwich Arsenal board nearly bit his hand off when Norris made his approach.

While retaining his directorship of Fulham, Norris became Arsenal’s chairman and tried to merge the two clubs

While retaining his directorship of Fulham, Norris became Arsenal’s chairman and tried to merge the two clubs to play at Craven Cottage, crucially north of the river. The League weren’t having it, nor his follow-up plan for each club to maintain separate identities while playing at the Cottage.

Plan C was to relocate Arsenal to Highbury, just far enough south of Tottenham and Leyton Orient to have a chance of attracting the masses of potential fans in the inner suburbs just north and east of the City of London.

The underground railway station at Gillespie Road – renamed Arsenal in 1932 – would deliver the punters direct to the turnstiles, guaranteeing gates that would justify Norris’s £125,000 investment (£50m today) in the hitherto dead-end club.

Plan C provoked outrage from all quarters: fans of Woolwich Arsenal, Spurs, Orient and even Chelsea united in condemning a scheme that would abandon one set of supporters and undermine the other three.

The Tottenham Herald caricatured Norris as a spike-collared Hound of the Baskervilles prowling round the Spurs roost, and mounted a campaign to keep the “interlopers” out. “They have no right to be here!” the local paper thundered, a sentiment echoed by Spurs fans ever since.

A vision backed by determination for fruition

Norris, a ruthless politician as well as a malignantly visionary strategist, was not going to be over-ruled by the FA a third time. He packed their inquiry with allies and got the vote.

Next, he squared local residents fearful of a riff-raff invasion every other week, and, thanks to a personal testimonial by his old pal the Archbishop of Canterbury, reassured the Catholic Church that the six acres of land belonging to St John's College of Divinity he proposed buying as the site for the club would observe the Sabbath and be free of liquor.

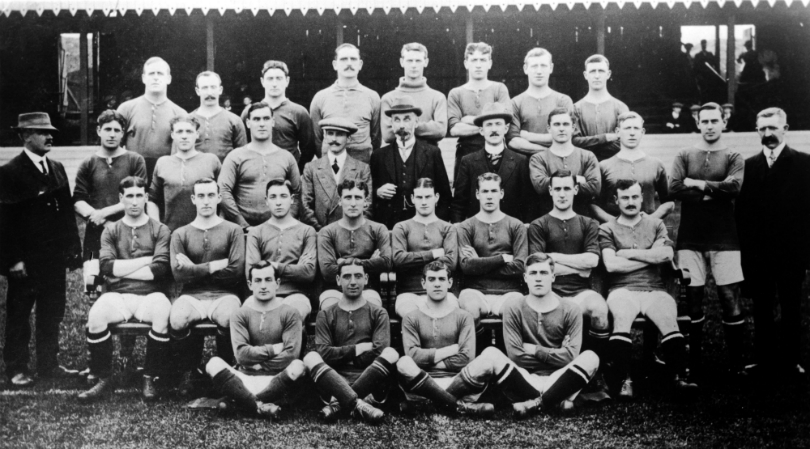

Arsenal played their first competitive game at Highbury, against Leicester Fosse in the Football League Second Division, on September 6 1913.

What of Spurs? Originally a cricket club, Hotspur FC was named after the rebel son of the Earl of Northumberland, whose family had owned Northumberland Park and other land around Tottenham.

Sir Henry Percy, nicknamed Harry Hotspur, was immortalised by Shakespeare as the chivalrous anti-hero of Henry IV Part One (his catch-phrase: “By heaven, methinks it were an easy leap/To pluck bright honour from the pale-faced moon”). The aristocratic cavalry to Arsenal’s roundhead artillery, the gulf in class between the two clubs goes right back to their roots.

The first London team to win the FA Cup – as Southern League amateurs, to boot – Spurs joined the booming Football League in 1908 and were promoted to the First Division in 1909. From that peak they slid until bottoming the table at the end of the 1914-15, when the Great War intervened.

Ending, meanwhile, the last pre-War season fifth in the Second Division, upon the return of peace Woolwich Arsenal would not expect to resume League football in the First Division. And yet they did – at Tottenham’s expense.

NEXT: Theories and conspiracies

Theories and conspiracies

Now there is a theory that Tottenham had repeatedly been frustrated over the years in its dealings with the Southern League, London FA and Football League because it had already acquired a Jewish support which was not smiled on by the football establishment in those days of widespread and open prejudice.

Moreover, so the conspiracy theory goes, the FA waved through Norris’s plans to build Highbury at the end of the Seven Sisters Road from Spurs for the same reason that the Catholic church granted the land – to undermine London’s top club on the grounds that it was too Jewish. Nothing can be proved.

What is certain is that Norris persuaded the 1919 FA League Management Committee that the fairest way to expand the First Division by two clubs was for the bottom club (Spurs) to be relegated and the next-to-bottom (Chelsea) to be reprieved on the grounds that its position was entirely due to a result that the High Court ruled had been fixed.

Manchester United’s 2-0 victory over Liverpool had saved the Red Devils’ top-flight status at Chelsea’s expense; that reversed result now doomed United and saved the Pensioners. Three clubs from the Second Division would make up the 22 – the top two at the end of the 1914-15 season... plus Arsenal, the fifth.

The official reason the committee gave was to reward Arsenal’s “long service to League football”

The official reason the committee gave was to reward Arsenal’s “long service to League football”, despite the fact that Wolverhampton Wanderers, who’d finished a place above Arsenal in 1915, had actually been in the League longer. The idea that visiting First Division directors might have voted for Arsenal because they looked forward to weekends away in the capital with somewhat more relish than trips to Wolverhampton or third-lying Barnsley is, of course, absurd.

As is the suggestion that the Committee President, ‘Honest’ John McKenna of Liverpool, in championing Arsenal’s cause was repaying Norris for his support in whitewashing his own club’s murky role in the match-fixing scandal of 1915. Or indeed that he received a cut-price house in Wimbledon through Norris’s estate agency...

Sick as a parrot – literally

When the news of their unwelcome new neighbour's bizarre promotion at Tottenham’s expense reached White Hart Lane, the club parrot, which had been presented by the captain of the ship on which Spurs voyaged home after their 1908 tour of Argentina, fell ill and expired. Hence the football cliché ‘sick as a parrot’. Arsenal have that on their consciences too.

Since then the fortunes of the clubs have see-sawed, seldom in equilibrium. Arsenal have never left the top flight; Spurs have oscillated. Tottenham’s glory years in the ’60s coincided with Arsenal’s spell in the wilderness that touched bottom on May 5 1966 when just 4,554 turned up at Highbury to watch them lose 3-0 to Leeds. Tottenham have never fallen quite that low.

For the fans, the animosity really started upon Tottenham’s return to the First Division after their 1919 relegation: on September 23 1922, trouble spilled out from the pitch onto the terraces at White Hart Lane when Spurs lost to two Arsenal goals scored by, wait for it, Reg Boreham.

“Spurs... the finer artists... extreme daintiness,” The Sportsman’s match report puffed its pipe appreciatively; “but Tottenham lost because they had nearly all the bad luck going in an amazingly strenuous contest... yet one could not help feeling impressed by the sledgehammer opposition of the Arsenal.”

Never mind that Spurs did ’em 2-0 at Highbury the following Saturday: that first outcome has been all too typical of the 56 league defeats Tottenham have conceded to Arsenal, compared to 45 victories and 36 draws – artistry bludgeoned by industry, playing with a more noble but less effective philosophy than winning at all costs.

NEXT: Switching clubs

Switching clubs

Nor have Spurs been lucky in off-pitch dealings with Arsenal. Few players have crossed the divide, but two stand out for the damage done to the morale of Spurs fans at vulnerable moments in the club’s fortunes: Pat Jennings and Sol Campbell.

It seems bizarre to think that Jennings remains a White Hart Lane hero, given that the Northern Ireland goalkeeper deliberately signed for Arsenal to embarrass Spurs directors, not one of whom thanked him for 13 years’ illustrious service when he was released for just £45,000 at the end of Tottenham’s 1976-77 relegation season.

Spurs fans may not have liked the direction Jennings chose to be pushed, but pushed he was

Spurs fans may not have liked the direction Jennings chose to be pushed, but pushed he was, and it was four years before Spurs had a keeper fit to fill Pat’s outsized gloves.

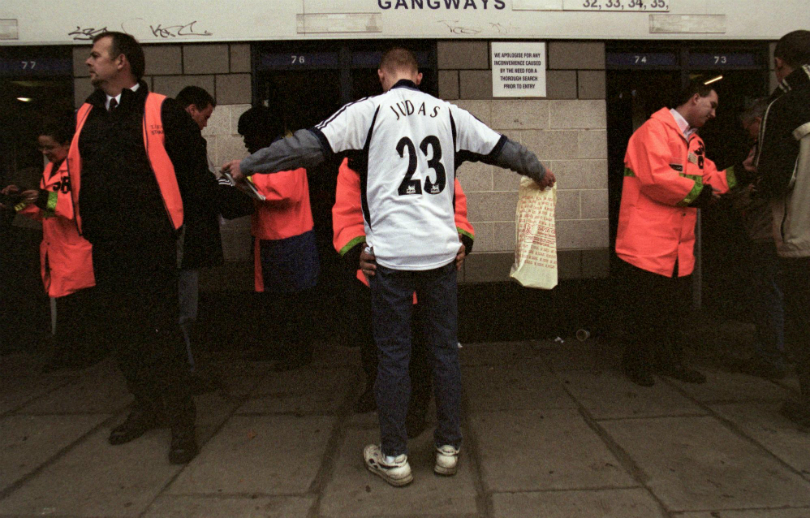

Being pushed was forgivable. Being pulled wasn’t. The last time Sol Campbell played for Spurs, it was as captain in April 2001 against Arsenal in an FA Cup semi-final at Old Trafford, injuring his ankle in a heroic effort that kept the margin of Spurs’ defeat down to 2-1. The next time he played at White Hart Lane, in November, it was in an Arsenal shirt.

He’d gone on a free that July after Arsene Wenger had publicly stated in April he would like to sign him. The Arsenal manager achieved his ambition in the face of Spurs not only offering Campbell 80 grand a week to stay but also a reported five-year contract offered by Barcelona.

Never in living memory was the derby so bitterly contested by Spurs fans as upon Campbell’s return; the phrase ‘cauldron of hate’ was coined for such atmospheres. Nor has the venom and vitriol directed towards Campbell by Spurs fans much abated, though the tone has softened since the initial purging hatred of the banners, boos and Judas chants.

Today you’ll occasionally hear sung from the cheaper seats knockabout ditties about his rumoured private life that, with some clearly vile exceptions, are homocomic rather than homophobic: the idea of this rock-jawed juggernaut in a romantic clinch with Michael Barrymore (to the tune of Verdi’s La Donna E Mobile) makes him a figure of fun who can be laughed off rather than an object of hate who can’t.

Whether such mockery is less acceptable in a football ground than it is in Little Britain is a topic for a heated debate

Whether such mockery is less acceptable in a football ground than it is in Little Britain is a topic for a heated debate on another occasion. Spurs officially are taking no chances: “strong action will be taken against those guilty... of harassment whether it concerns race, religion or sexuality,” warns the matchday programme.

But, after four years, the Spurs fans seem to have got to Campbell. His performance at White Hart Lane in October was a model of panicky ineptitude which set the standard for the rest of the season since.

When Arsenal fans, as they now do, grumble that Spurs are welcome to have Campbell back, Spurs fans can last feel satisfied that rough justice has been done: disloyalty is rewarded with disloyalty. Not that the bitterness has penetrated the boardroom.

Where relations between the two sets of directors in the past has seen coldly formal, today Arsenal vice-chairman David Dein’s son Darren is married to former Spurs vice-chairman David Buchler’s daughter, having previously dated Alan Sugar’s daughter. As an insider explained, belonging to the Premiership is too much of a good thing to let the small matter of time-hallowed mutual dislike get in the way.

The North London derby looks set to reclaim its title as the most keenly awaited fixture of the season

Campbell’s decline for Arsenal coincides with Ledley King’s assured establishment at Spurs: defensive rock, captain and frequent England choice. The Spurs end of the see-saw seems to be swinging back up. Even St Totteringham’s Day – the date on which it’s mathematically impossible for Spurs to catch up Arsenal in the league; “it seems to come round earlier each year!” gloat the Gooners – might not be celebrated this season.

With Chelsea’s lock on the title probably secure for many years, Arsenal’s rivalry with Man United now seems to be a sideshow, so the North London derby looks set to reclaim its title as the most keenly awaited fixture of the season.

NEXT: Bonus! Famous fans of each side discuss the rivalry

It's all about the suffering

Racism, banter, geography, dread and idiot cousins: the fans describe Arsenal vs Spurs

Danny Kelly Spurs

"Being born and brought up near Highbury, I should be an Arsenal fan, and I used to get taken there and to White Hart Lane – my family are mostly Arsenal, and my girlfriend now is a season ticket holder. But even then I saw one lot was the Foreign Office in red shirts while the other were the true spirit of rock’n’roll – the white shirts represent purity to me.

"At school in Islington I was in a minority but it wasn't such a huge issue then – you didn't define yourself so much by who you were against. For me the crisis came in '71 when Arsenal won the Double and held the victory parade in Islington. My family trooped off with cardboard trophies, leaving me behind to hear the roaring from the High Street. At that moment I realised that life was not necessarily going to be fair."

Lloyd Bradley Arsenal

"In the '60s I went to school between the two grounds. Arsenal were the underdogs then. Most of the first XI supported Spurs, while more black kids, including me, played for the Arsenal playground team. My mates and I would go to Arsenal one Saturday and Spurs the next – and we'd support Spurs against any northern side.

That's what perturbs me about this season - Spurs aren't the idiot cousin down the road you can patronise anymore

"All real football fans are the same: it's about suffering, so gentle geeing up always gets to someone more. You couldn’t fight with kids then sit together in class on Monday. Spurs fans would talk about how we hadn’t any class, so recently we've loved taking the piss because we were more successful and playing good football. That's what perturbs me about this season – Spurs aren't the idiot cousin down the road you can patronise anymore."

Jim O'Neill Spurs

“The rivalry is more intense now than in the '60s and 70s. When Pat Jennings left Spurs for Arsenal he got applauded when he came back to the Lane, but Sol Campbell needs an armed guard. Back then, people would alternate, Tottenham one week, Arsenal the next. When Arsenal won the Double in '71, l spotted a bloke on telly my brother stood with in the Shelf [at White Hart Lane] supporting Arsenal at Wembley!

"Couldn't happen now, and not just because of the cost and having to book ahead. No one lives near the grounds anymore, they live out in Harlow, Stevenage, the suburbs. Also, the need to win at all costs and at all levels – managers, players, fans – is much more intense. I love watching Arsenal lose now almost as much as watching Tottenham win."

Arsenal were the dour and unattractive alternative to Spurs' glory glory side. Until the Wenger era that remained so

Simon Kanter Spurs

"Arsenal have always been the enemy and always will be, whatever Chelsea’s aspirations. Arsenal were the dour and unattractive alternative to Spurs' glory glory side. In 1971 they ground their way to the Double, unlike Spurs' 1961 free-flowing Double side. Until the Wenger era that remained so. It’s been hard to stomach watching Wenger's Arsenal playing Spurs-style football, especially while we've been so woeful in that respect."

Nick Hornby Arsenal

"In Fever Pitch I wrote that Spurs fans had a smug air of ersatz sophistication. That Arsenal under Wenger have played the space-age version of the football Spurs aspired to must have been extremely galling. The derby stopped being a big game, just sound and fury. Then they turned a bit nasty like in 2001 when Sol Campbell said he was leaving Spurs for Arsenal for football reasons, everybody knew what he was talking about and that ratcheted up an already bitter situation.

"Yet Spurs could absolutely have done what Arsenal did – they could have had Bergkamp, Petit and even Wenger. Now, this season, with Carrick, Robinson and Defoe, it's beginning to look the other way. The last few weeks I've remembered what it feels like to be a football fan. For 10 years it’s been like going to the cinema or a rock concert – you’re entertained, but at a distance. If Arsenal beat the likes of Sunderland by less than four goals, it felt poor value for money. Abramovich has brought back the importance of the derby. The Premiership doesn't matter because you can't win the f**king thing anymore."

This feature originally appeared in the May 2006 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe!

World's Biggest Derbies • More Than a Game