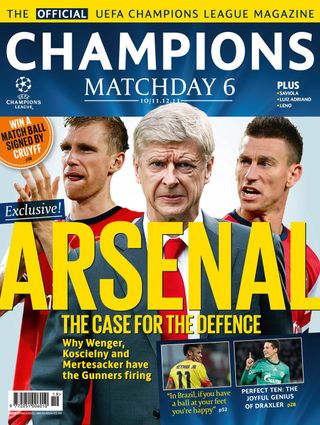

Analysing the superhuman resilience of Arsene Wenger

The Frenchman may be in his 18th year of managing Arsenal, but, writes Champions Matchday editor Paul Simpson, he is still steadfast in his vision for the club...

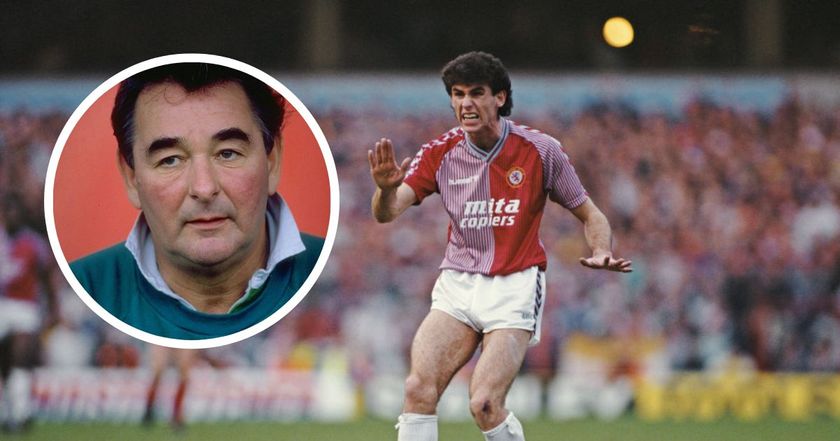

We live in an age where coaches are professionally obliged to be superhuman. An age in which – with every tactical ploy questioned by the Twitterati, every team line-up challenged by bloggers and every performance scrutinised by a horde of headline-seeking pundits – a manager can feel as if they are at the epicentre of, to quote Martin Amis, a “moronic inferno”.

Football management has never been a job for the weak-kneed, indecisive or plain idle, but the ritual sacking of coaches this season suggests the pressure is greater than ever.

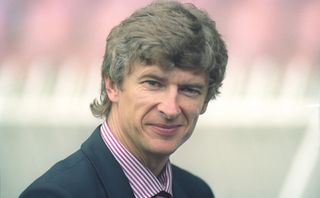

Arsène Wenger would probably disagree. In one interview conducted by this writer, it quickly became clear how punishing the years before he coached Arsenal had been for him.

Sitting in his office at the club’s London Colney training ground 11 years ago, Wenger was remarkably candid about his apprenticeship in the dugout – a time when, he said, he feared he would have a heart attack because watching his side lose was so excruciating. As he suggested wryly: “I would pray to God my team would win. Later I thought I ought to pray for better players.”

Unlike his friend Gérard Houllier, Wenger didn’t have a coronary. Even though his first club, AS Nancy – where he had been recommended by Michel Platini’s father Aldo – were relegated while he was in charge, he learned to cope. He built a stylish AS Monaco team that won Ligue 1 in 1988 but was denied more silverware by Bernard Tapie, Olympique de Marseille’s president, who paid off opponents with such largesse that one of his accomplices had to store a cache of banknotes in his back garden.

A life-changing crisis

For a man who cares as deeply about football as Wenger, this was more than a scandal – it was a profound, life-changing crisis. His modest playing career had started at AS Mutzig, a club renowned for playing the best amateur football in Alsace, in 1969. At that time, the game was held in such low esteem in France that “if you wanted to impress a girl at a party, it was better to say you were a student than a footballer.”

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

His game had always been more about tactical vision than technique and he seemed destined to become a coach. He had flourished at Monaco but the match fixing was an ugly, agonising, faith-testing, business.

If Wenger has sometimes seemed acutely sensitive – some say over-sensitive – to questions of morality in football, it is easy to understand why. In retrospect it was probably lucky for him, Arsenal and English football, that Monaco, after refusing to let him manage Bayern, dismissed him in September 1995.

His move to Japan, to coach Nagoya Grampus Eight, was an audacious bid to banish the ghosts of Tapiegate. Yet, in a new exotic culture he grew to love, he faced an even greater challenge.

In our interview, he made no attempt to gloss over how difficult his introduction to Japanese football had been: “You wake up in the morning, you can’t speak a word of the language, there’s no one who can really understand you and yet there are 20 or 30 players who expect everything from you.”

His sense of moral obligation – his belief that he could not go back on his word and break his contract – kept him going. Somehow he got his message across – the Nagoya players still recall his mantra: “Pass the ball into the future.” As the results improved, Nagoya won two cups. As he says in the current Champions Matchday: “Happiness in our life depends upon the next result.”

When Wenger came to Arsenal, he quelled the “Arsène who?” jibes by presiding over a scientific revolution and reinventing the club’s style of play. Since he took over in 1996, London Colney has become a mecca for ambitious coaches, with Laurent Blanc, Glen Hoddle, Jürgen Klinsmann, Ralf Rangnick and Matthias Sammer just a few of those who acknowledge his influence.

They are not coming to study Wenger’s tactical innovations. Once a firm advocate of 4-4-2, believing it was scientifically proven to cover more of the pitch, he has proved flexible enough to adapt to 4-2-3-1 and 4-3-3.

Yet his broader vision has remained constant. A fervent admirer of Rinus Michels’ Total Football, he has striven to create teams that are fluent, flexible and stylish in the tradition started by that innovative Ajax side. It hasn’t always worked, yet in a game where three defeats can spell dismissal, the consistency of his vision is impressive.

What coaches come to observe is how he runs his training sessions, the attention to detail at the facilities and to see if they can identify how it is that, as Gooners say, “Arsène knows”.

How can he look at a misfit on the wing at Juventus and see the greatness that would become Thierry Henry? The metamorphosis seems inevitable now but when Henry first signed, as Nick Hornby recalled: “My brother said we’d spent £10m on the French Perry Groves.”

Stubbornness or resolve?

Four years ago, Wenger told the League Managers Association: “I never have days when I think I can live without football.” Indeed, he admitted that, during a season, an hour without football was a rarity.

That hasn’t changed. Talking to Champions Matchday, he says: “When you are young, you think I will make it because I am talented. You learn slowly in life that you have to be absolutely committed.”

The flak he has endured in the last few seasons – ranging from legitimate criticism to xenophobic vitriol – has not created any self-doubt or affected his commitment. Where naysayers see stubbornness, others see resolve.

The fact that he shares the first five letters of his name with the club he manages seems richly symbolic. While it is still possible for Manchester United fans to look past Sir Alex Ferguson and glimpse the glory of Sir Matt Busby, Wenger has all but obscured the memory of such predecessors as George Graham, Bertie Mee and Herbert Chapman.

Wenger has become as synonymous with Arsenal as Steve Jobs was with Apple. And, though his departure from the club seems a distant prospect, he will be as hard to replace.

Champions Matchday is the official magazine of the UEFA Champions League. It is available across Europe on the newsstand and also comes in digital versions which can be purchased via Apple Newsstand. You can also follow the magazine on Twitter @ChampionsMag.

Most Popular