Anchovies, turncoats and lighters: Why Olympiakos vs Panathinaikos is more than a game

Athens: the cradle of democracy but also of a class war that rumbles to this day. From FourFourTwo magazine, December 2005

It’s a baking hot August afternoon in Athens, and FourFourTwo is feeling ill at ease.

August 28, 2005 marks the first day of the new Greek season, and the city's Olympic Stadium is playing host to the country’s most eagerly anticipated game: Panathinaikos versus Olympiakos, rich versus poor, underachievers versus all-conquering champions, all played out before 60,000 bloodthirsty, baying locals.

If the fact that the stands around us are alive with flames isn’t of concern, the arrival, just yards from our seat, of a group of dangerous-looking youths carrying lighters most certainly is.

“They've been waiting outside so they can sort out any Olympiakos fans looking for trouble,” smirks the man beside us, who moments earlier had been standing, jumping and swearing at the visiting players. “When they find Olympiakos fans, they steal their scarves or banners and burn them as a sign that they have won that battle.”

Sure enough, small pockets of fire rage around the stadium, each new flame greeted with another almighty roar of approval. The front of the man’s Panathinaikos shirt bears the legend ‘Everybody Sucks’. On the back it says ‘Except Us’. Welcome to the siege mentality of the Athens derby.

'The fans hate each other, the players hate each other and the managers hate each other too,' explains FourFourTwo’s neighbour, summing up the relationship nicely

Tension is never far from the surface when Athens’ big two meet. Rival fan gangs regularly clash before, after and often during games, and with a history of brawling between the players too, emotions are rarely kept in check.

“The fans hate each other, the players hate each other and the club managers hate each other too,” explains FourFourTwo’s neighbour, summing up the relationship nicely. “We hate what Olympiakos represent, which is why winning this game is one of the most important things for us this season.”

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

According to Panathinaikos nut George, who runs the greenwebfans.com online community, the rivalry is very easily defined. “We are humans and they are dirt,” he spits, his voice already croaky from pre-match shouting. “Every Panathinaikos fan knows that he is superior, even when he meets a Gavros fan at the age of five.”

I was born hating Panathinaikos because my father hated them and my grandfather hated them. We were born into a low class and we are not as rich as them

The word Gavros translates as ‘anchovy’, a reference to the fact that Olympiakos are located in the city’s port area of Piraeus. “The majority of Gavros fans have mothers who are hookers who ‘work’ near the port,” laughs George. “Their fathers are young sailors who slept with a hooker.” To spread the word, he rejoins his green-shirted crew as they belt out another chant based on prostitutes, sailors, and Olympiakos players.

Earlier, Markos, an Olympiakos regular, offered an alternative view. “I was born hating Panathinaikos because my father hated them and my grandfather hated them. We were born into a low class and we are not as rich as them, that’s the difference between them and us.” That social distinction provided the initial marker for a rivalry which has grown more fractious with every encounter.

Rapid degeneration

Panathinaikos – abbreviated to PAO – was founded in 1908 by a group of athletes born in Athens (hence the name), who sought a team to represent their noble standing. Olympiakos arrived some 17 years later, formed by residents of the port town of Piraeus who wanted an alternative – they named it after the Olympic games, the noblest expression of the sporting spirit.

Piraeus may only be 10 miles from the centre of Athens, but its inhabitants thought themselves independent of the bourgeois city-dwellers. The Athenians, meanwhile, considered the port to be where the poorest people lived and the loosest morals prevailed. The differences soon became apparent on the football pitch, as matches between the two degenerated into a battle of the social classes, a fight for pride and prestige as much as the result itself.

The first violent skirmishes between the club’s followers broke out in April 1933, when fans clashed furiously after a League Cup semi-final was abandoned at half-time because of a freak rainstorm. With the tone set, resentment simmered on a high heat until finally erupting again in March of 1949, when Olympiakos fans became angered that one of their players had been knocked unconscious and trampled over as the referee waved play on. Invading the pitch, they administered justice of their own by hospitalising two of the visiting players.

Olympiakos were reduced to nine men after half an hour. With the match suspended twice and the referee having to seek shelter from missiles raining down on him, the first half lasted 66 minutes

And so it continued, with general ill feeling periodically punctuated by acts of violence and bloodshed. At the Greek Cup Final in June 1962, two players were dismissed for fighting inside the first five minutes. Olympiakos were then reduced to nine men after half an hour after the red mist descended again, and with the match suspended twice and the referee having to seek shelter from missiles raining down on him, the first half lasted 66 minutes.

After a 35-minute break for half-time, extended to clam both players and supporters, plus a further 45 minutes of football, the teams entered extra-time with darkness rapidly descending on the Nea Filadelfia, a stadium with no floodlights. The referee had no choice but to suspend the match, with both sides bitterly blaming each other for the violence.

The Greek FA, concerned about the implications of a replay, decided against scheduling a second game, hence the history books recording that Greek football had no cup winner in 1962.

If the Greek Football Association thought the fans would mend their ways as a result of that encounter, they soon knew better. Just two years later, the sides were drawn to face each other in the Greek Cup semi-final, in a match played out during a heatwave. With the game goalless and neither side seemingly interested in attacking, the crowd became restless.

Murmurings quickly spread that the match had been fixed so that both clubs could make money from a replay, and when a rare opportunity ended up in the stands, the spectators had seen enough. As one fan plunged his knife into the ball, others rampaged through the stands and onto the pitch, leaving a trail of burning seats and advertising hoardings in their wake.

In 1973, it was the players’ turn to misbehave, sparked by a dispute over whether Yves Triantafyllos’ 18th-minute equaliser for Olympiakos had crossed the line. As Panathinaikos defenders harangued the referee, play was suspended for 10 minutes and when it did restart, a PAO defender wasted no time in punching Triantafyllos in the face to earn both players red cards.

Ten minutes from time, tempers boiled over again when PAO appeals for a penalty were turned away. Amid the chaos, PAO’s Athanasopoulos was sent off for attempting to stop the fist-fight between two other players and, in protest, the Panathinaikos players walked off. The Sports Court later awarded the victory to Olympiakos.

Any sport will do

Since then, violent outbreaks have been depressingly common (notably in 1986, when Olympiakos fans took their anger out on their own players’ cars after a 4-0 Greek Cup Final defeat), and the rivalry has even infiltrated other sports.

The intensity would still be present if these two teams were picked to play ping-pong

“If these two teams were picked to play ping-pong,” says former Olympiakos keeper Dimitris Eleftheropoulos, now at Roma, “the intensity would still be present.” To prove the point, when the two sides faced each other in basketball’s EuroLeague semi-final in 1994, Olympiakos edged out PAO after another violent encounter.

The fans, players and management of Panathinaikos responded by openly supporting Spanish side Badalona in the final, a very deliberate, very public snub which merely served to heighten the ill feeling between the clubs.

Nor have the men running the clubs done much to quell the hostility – quite the opposite, in fact. Olympiakos president Socrates Kokkalis rarely misses an opportunity to brand PAO “chickens” in the press, while Panathinaikos president Angelos Philippides outdid furious fans and players alike in March 2002 when he attacked referee Makis Efthymiadis for awarding Olympiakos a last-minute penalty in a 1-1 draw.

Unbelievably, Philippides then had the nerve to claim that Olympiakos were only in the headlines because of the activities of their Ultras. “While Panathinaikos is putting Greek football on the front pages with its European successes, fans of another team are making front page news by bringing the game into disrepute,” he said after rioting Olympiakos fans broke shop windows after a league game at Xanthi.

NEXT: Those who dared swap sides

Later that season, as hostility escalated, Panathinaikos players claimed they had been intimidated by Olympiakos security staff, accusing them of breaking down the dressing-room door and threatening players before the title-decider between the two sides in May. Olympiakos won the game 3-0 to take their eighth title in nine years and their 33rd in all.

The only reason the 'Anchovies' had success is because their president has gained control of the referees and the Greek FA

And despite the brave face PAO fans present, therein lies a more recent source of resentment. Struggling to keep pace, Panathinaikos have won just six titles in the last 20 seasons, and 19 in total.

They point to, and arguably clutch at, a superior record in European competition as the only Greek side to have reached a European Cup Final (even though it was back in 1971, when they lost to Ajax at Wembley) as well as three semi-finals. In contrast, Olympiakos’ best performance is a quarter-final appearance in the 1999 Champions League.

“The only reason that Gavros has had a run of success in Greece is because their president has gained control of the referees and the Greek FA,” shrugs George, as if his unsubstantiated theory is fact. “As a result, Panathinaikos and the other Greek teams not only have to beat Gavros, they have to beat the referees, then beat the Greek FA. It is sad, but it’s the way it is.”

Laughing dismissively, Markos disputes such accusations. “We don’t care what they say about Kokkalis because their owners are even worse than he is,” he shrugs. “We are the best team in the country not because of cheating but because we sign better players every season.”

Swapping green for red

This summer, Olympiakos signed five new players, parading them before the press just days after the fixture list had been released. But no one was interested in the thoughts of Yaya Toure, Tasos Kyriakos, Mihalis Kapsis or Charilaos Pappas.

Instead, all eyes were on Cypriot striker Mihalis Konstantinou, the self-confessed boyhood Panathinaikos fan who ran his four-year contract down with the Greens before joining Olympiakos this summer as a free agent. The move shook the foundations of Greek football.

Konstantinou had originally turned down Olympiakos in favour of signing for Panathinaikos in 2001 for £7.5m. Though some way short of prolific in his first three seasons at the club (18 goals in 64 league matches), he quickly became a favourite of the PAO fans.

I am turning a page in my life and I don’t want to speak about the past. I believe I honoured my contract with Panathinaikos for four years

It helped that many of his goals were spectacular efforts, and it helped that he scored two crucial goals against Olympiakos to win the 2004 Greek Cup Final. But it helped far more that Konstantinou had been a Panathanaikos fan all his life. “I even had posters of our players on my bedroom walls,” he proudly boasted.

Little surprise, then, that the Olympiakos supporters had been the first to barrack Konstantinou whenever they could. They called him a palto, which literally means a coat, but refers to an over-priced purchase that’s not worth the money. The two Olympiakos-supporting newspapers, Protathlitis and Fos, quickly capitalised, labelling Konstantinou a palto at every opportunity. But that was then, before the move to Piraeus.

“I am turning a page in my life and I don’t want to speak about the past,” Konstantinou told the press. “I believe I honoured my contract with Panathinaikos for four years. That contract was over and afterwards I received an offer from Olympiakos. I will give my best and I believe I will score lots of goals for my new team.”

The irony of his first game being against his former team was not lost on Konstantinou, but he was quick to play down its significance. “That game would come eventually, so it doesn’t matter that it will be my debut for my new club.”

It clearly matters to the Panathinaikos fans, whose Ultras compose a song for Konstaninou’s debut which they distribute via SMS and the internet before the game (even if something is lost in the translation):

“Mihalis, look at what a sorry sight you are.

You have become a rat and you never respected us.

We will call you a sorry arse forever.

You would even have joined Attila’s Turks if there was money in it for you.”

Not everyone will be joining the chorus. “Singing would be like honouring the bastard,” spits PAO fan George. “But it’s OK, because maybe in 10 years he will sell one of his kids to earn some more money.”

Nor can Konstaninou count on support from Olympiakos fans. “I cannot sing for someone I wanted dead,” says Markos ruefully.

As the players run out for their pre-match warm-up at the Olympic Stadium – Panathinaikos’ temporary home while their Apostolos Nikolaidis is refurbished – the home fans direct their abuse and frustration at Konstantinou.

Just a few hours earlier, some 100 of them had greeted the Olympiakos team bus with a shower of bottles and expletives, and as Konstanatinou works through his stretching exercises, the Greens unfurl a banner proclaiming: “We knew that you were not a man. We did not know that you were a greedy parasite.” As the tension builds ahead of the kick-off, the PA system blares out a Cypriot song about money, with the implication quite clear.

I was disgusted with the way Panathinaikos treated me: they insulted me. They're probably happy now that I'm at Olympiakos: they have an excuse for their actions

Though he may be the focus of most attention, Konstanatinou is by no means suffering alone today. Olympiakos goalkeeper Antonis Nikopolidis is another defector on show, having spent 15 seasons at the Olympic Stadium.

He’d almost certainly still be with the club today, were it not for a contract dispute in December 2003, when Panathinaikos refused to match his £400,000-a-year wage demands. Demotion to the bench followed, before Olympiakos stepped in and snatched him away.

Panathinaikos fans accepted that their club had treated him badly, but to this day they struggle to comprehend how he could have moved to their most despised rivals.

“I was disgusted with the way they treated me at Panathinaikos,” said Nikopolidis, by way of explanation. “They insulted me and I think they are probably happy now that I moved to Olympiakos because they now have an excuse for their actions as they can claim they knew my intentions.”

On his first return to PAO’s Apostolos Nikolaidis stadium last April, Nikopolidis was man of the match, though he couldn’t prevent a 1-0 defeat, the goal scored, ironically, by Konstantinou.

To welcome him back, the home fans had printed giant banknotes with his face on them and strung up a dummy of him from a noose. Nikopolidis refused to react to the abuse until, midway through the second half, he sarcastically applauded a song about his family and the prostitutes of Piraeus.

Unsurprisingly, fans continued the song until the end of the game, then went home and penned an amended version for today’s game…

“Antonis, you are a traitor, and a pussy.

They brought you Mihalis so you can have a friend.

We will f**k you Antonis, because your God is money.

F**k your Olympiakos.”

NEXT: Grab testicles, become hero

Grab testicles, become hero

Under the smoke of stolen spoils, the game kicks off and, as befits many derby games, it’s a tight, tense and tetchy affair. Konstantinou struggles to make any kind of impact, while Nikopolidis is called into making only one comfortable save, and the first half belongs to the more accomplished visitors. Clearly sensing the danger, Alberto Malesani, the former Parma coach now leading Panathinaikos, prowls his technical area, barking orders at anyone within shouting distance.

After half an hour, those orders fall on deaf ears as Olympiakos captain Predrag Djordjevic fires in a free-kick from the left for an unmarked Akis Stoltidis to head past Mario Galinovic in the PAO goal.

It’s a sloppy goal, down to an early-season lack of concentration, and as Konstantinou joins in the celebration, the cheers of the away followers are quickly drowned out by an irate roar from the Panathinaikos fans.

An hour in, and Panathinaikos are reeling again, this time from the dismissal of Ilias Kotsios for violent conduct. As Yiannis Okkas drops to the ground as though poleaxed by a sniper, referee Thanasis Briakos brandishes a straight red. “There was no contact,” snorts the man beside me. “The referee was just carrying out the orders of his boss, Kokkalis.”

The decision ends the game as a contest. Panathinaikos rarely threaten an equaliser – even after the arrival of substitutes Nordin Wooter and Igor Biscan – and in the final minute Djordjevic’s pace sends him clear to drill low past Galinovic and seal the victory.

It’s clearly too much for Panthanaikos central defender Nasief Morris, who turns towards the celebrating Djordjevic and kicks him hard on the calf. As Briakos brandishes red again, Morris removes his green shirt and throws it at the official as he trundles off.

On a day of dismay, the home fans admire the flagrant display of dissent and roar their approval as Morris heads straight down the tunnel. The authorities will be less generous, though, later banning him for four games and Kotsios for three.

At the whistle, according to unconfirmed reports, Olympiakos defender Grigoris Georgatos celebrates victory by grabbing his testicles and shouting, 'Now you can suck my d**k'

By the time Konstantinou is taken off in the final seconds, the PAO fans can barely muster an acknowledgement as he makes for the tunnel.

At the whistle, according to unconfirmed reports, Olympiakos defender Grigoris Georgatos celebrates victory by grabbing his testicles and shouting, “Now you can suck my dick” as the Panathinaikos players file by to their dressing room. True or not, such an act secures hero status for Georgatos among his own fans and suggests the hostilities are unlikely to die down any time soon.

In the weeks since the game, normal service has resumed. Olympiakos are cutting a swathe through domestic football and, at time of writing, are top of the table with a 100% record. Their European form is still off the pace, however, and after losing narrowly at Real Madrid, they still await their first away win in the Champions League after eight years and 26 games of trying.

Across the city, Panathinaikos are lagging in the league but seem well placed to progress from their Champions League group. “Once again we are hoping for European success as it seems the referees will do all they can to help Gavros win the title,” whispers George, two days after the derby, his throat still tender after several hours of shouting. “That opening-day result will set the tone for the rest of the season in Greece.”

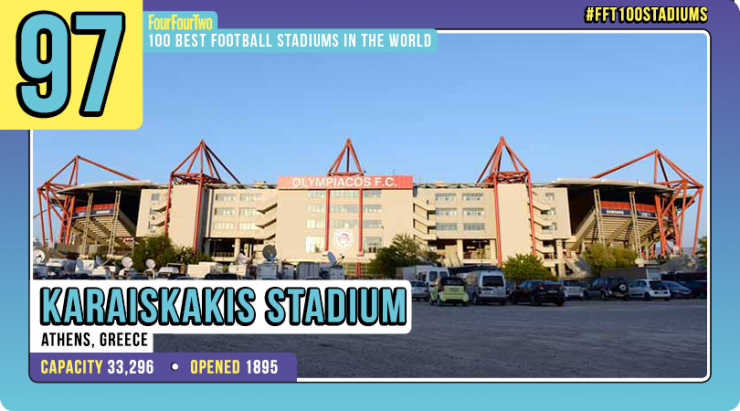

Like everyone else in Athens, he is already looking forward to the return game at Olympiakos’ Karaiskakis Stadium, scheduled for next January. It will take him until then to get his voice back.

This feature originally appeared in the December 2005 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe!