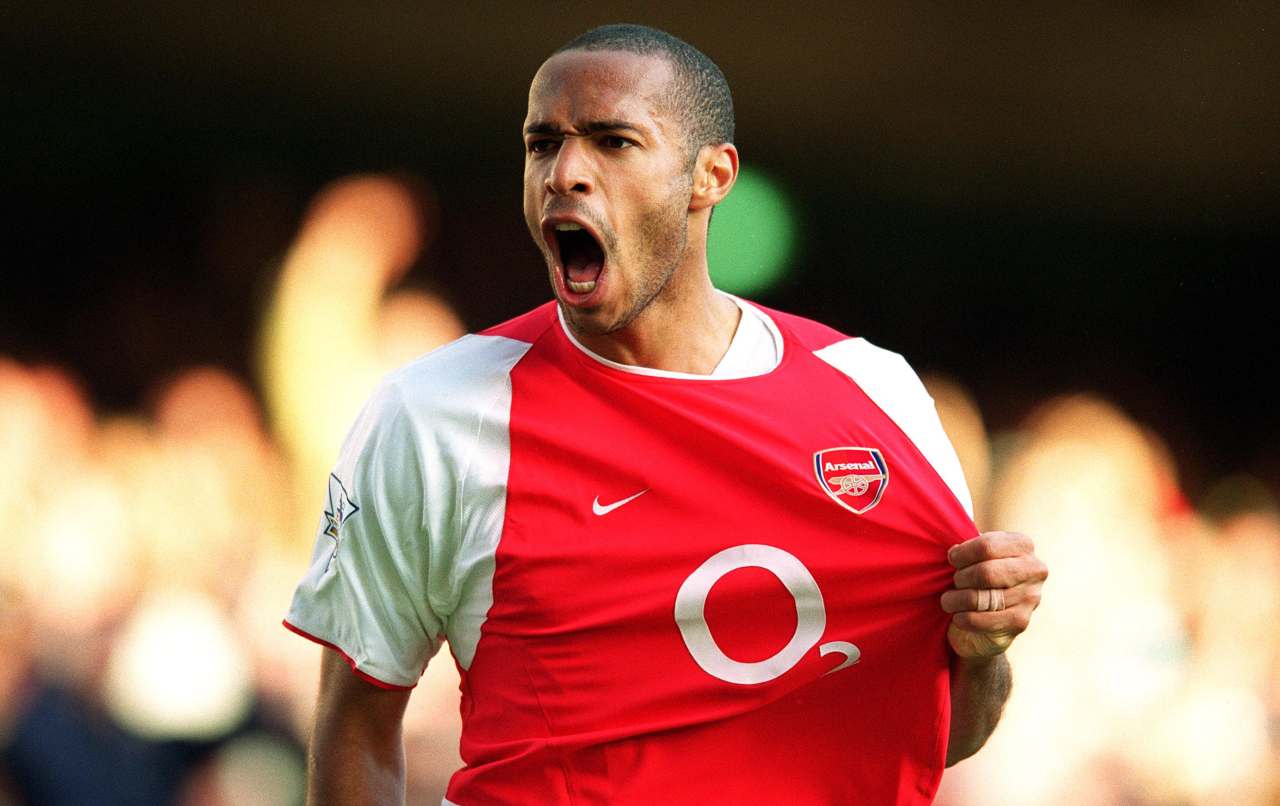

Arsenal legend Thierry Henry chats to FFT: “Why did I want to become a manager? Maybe because I’m crazy”

Thierry Henry made Arsenal fans the envy of football over eight years in north London, but little has gone his way in the dugout to date. The Gunners great talks FFT through his battle as a boss – and why the dream of coaching his beloved club will never die

This feature first appeared in the April 2021 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe now!

”There’s one thing that Arsene tells me all the time. ‘Enjoy the ride and all the best,’ he says, ‘because it’s not easy...’ And, yes, he’s right. It’s not.”

Thierry Henry briefly bursts into laughter as he repeats Arsene Wenger’s words, but he’s never been so serious about anything in his life. He’s recounting the most regular piece of advice he’s received from his former Arsenal boss since embarking on his own management career.

That career may have been short so far, but Henry has already been through enough stresses to understand the subtle humour Wenger intends – akin to the advice he might offer someone heading off for their first day as a lion tamer, or a daredevil about to hurl themselves over Niagara Falls in a barrel. Good luck, son: you’re going to need it. If you don’t come back, it was nice knowing you.

Football management is almost as perilous. Admittedly there is a reduced risk of being horribly savaged by a big cat, but some of the sport’s most iconic names have had their reputations torn to shreds after an ill-fated venture into battle.

France’s greatest ever goalscorer and Arsenal’s greatest ever player, Henry could have sat at home for the rest of his life and watched Premier League Years on a loop. But he didn’t want to do that. He had a burning desire to become a manager – and at the beginning of 2021, that desire remains as strong as ever. His three-month spell with Monaco from October 2018 was as brief as it was difficult, then came a challenging year in charge of MLS outfit Montreal before he resigned for personal reasons to be closer to his family. So what now?

Over the course of a lengthy conversation with FourFourTwo, Henry’s determination to make it is to become abundantly clear. This is not a man who’s content to manage solely by virtue of his status, with little knowledge of football below the very elite. He’s poured his heart and soul into it, caring as deeply about succeeding in Ligue 1 or MLS as he did during any title race with the Gunners, and working just as hard to make it happen.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Sat in front of us is a man clearly keen to outline his philosophy. And if you ever need to know anything about Newport County or Bala Town, he can tell you about them too…

“When the war is over, the soldier can cry”

Nothing has been stress-free about Henry’s managerial career. After thrusting himself into a relegation battle at Monaco – only to be swiftly thrust back out of it again – his first season at Montreal became dominated by COVID-19 chaos. The Canadian side were affected more than most.

Appointed three months before the 2020 campaign got underway, Henry took four points from his first two MLS games in charge when coronavirus put a stop to everything. Montreal didn’t kick a ball until July’s ‘MLS Is Back’ mini-tournament in Florida. They then briefly returned to league action in Canada, before quickly having to switch their home matches to New Jersey due to restrictions over cross-border travel.

“When you’re a new coach with new ideas, it’s very difficult to put something in motion when you have to stop every two months,” explains Henry. “You need to understand something with me – I like to state facts and sometimes if you state facts, people think you’re complaining. I’m not, but it’s tough to stop and go all the time with a new culture, a new way of playing.

“We went to MLS Is Back as one of two or three teams a month behind everybody in terms of training, then if you don’t perform, you get hammered. You play in Orlando – hot, humid – then you return to Montreal, go into quarantine for 14 days and can’t train, then you come out of quarantine and have to play straight away.

“Then we had to play all our games away from home. We made the play-offs, but last year was very challenging.”

This had all added further complications, in a profession that’s highly complex at the best of times. “It’s time consuming – you have to think for everybody,” says Henry.

The Frenchman had known for a long time that he wanted to take on the challenge of management. Following retirement, he soon established himself as a pundit on Sky Sports – his most notable moment perhaps grabbing Jamie Carragher’s leg in meme-tastic shock, after Brendan Rodgers’ Liverpool dismissal was announced live on air in October 2015. Henry could have remained at Sky for years, watching managers come and go from afar, without making the move into the pressure cooker himself. So why didn’t he?

https://t.co/1ynq7QJmbc pic.twitter.com/HqXgmbldLyMarch 12, 2021

“Maybe because I’m crazy,” he chuckles.

“I knew I was always going to stay in the game. As a player, I’d always been interested in tactics and challenging my coach. I was a real pain in the neck. If they didn’t put the cones exactly where they were supposed to put them, I was like, ‘It’s too short’. I was always challenging, ‘Why are we not playing like this?’ It was even a bit too much at times. But I was always thinking about games and watching games. What can you do better?

“So I said to myself, why not become a coach? It’s a passion, it’s what I like to do. I go onto the field and you have to tell me to stop. Sometimes the players are like, ‘Coach, we’ve been on the field for a long time’ and I say, ‘Oh yes, sorry...’ You feel the pressure, because you’re a manager. Were you feeling pressure when you were about to play, too? Well, yes, but it’s like breathing. I don’t think about breathing.”

Henry coped with pressure as a player to become an all-time great. Not everything was perfect – Ireland supporters are unlikely to forgive or forget his Hand of God moment in qualification for the 2010 World Cup – but few have enjoyed a career so resoundingly successful. It brought him the 1998 World Cup, Euro 2000 and the 2008-09 Champions League, as well as league titles with Monaco, Barcelona and his beloved Arsenal. Recently, FFT crowned him the best player in Premier League history.

“Thank you for that,” says Henry, humble enough to accept every single compliment, no matter how many he’s already received during his life. “I wouldn’t change anything about my career. I’m happy with what I did, and sometimes that’s not so much about winning. Winning matters, but it’s what you transmit to people.

“That’s why my relationship with Arsenal fans is special, because we cried together, we experienced joy together. They felt what I felt – we were as one. When people see your heart, they’ll like you. Sometimes it could be, ‘Whoa, he doesn’t look too happy today, he’s having a go at someone or he’s about to lose it’. But people can relate to that – it shows that you’re human.

“Without your team you are nothing, as you talk about individuals when the team wins titles. But I’ve learned to appreciate individual recognition – you realise that you must have done something OK with your team and left a print. Not only with trophies, but the way you played, the way you battled, the desire to always show up.”

The GOAT. The King.Call him what you want: he's ours and he's the best the @PremierLeague has ever seen 💯🐐 @ThierryHenry 👑 pic.twitter.com/M0rAG0I4vwAugust 17, 2020

Henry didn’t just drive himself on, he drove his team-mates to ever greater heights, too. When Netflix screened their 10-part series about basketball legend Michael Jordan last year, perhaps the finest insight yet into the relentless mentality of an elite sportsperson, former Arsenal striker Carlos Vela told the US media that Jordan’s approach very much reminded him of Henry.

“Thierry tried every day to be the best and pushed the young guys to work more, to bring everything to every training,” revealed the Mexican, now at LAFC.

Henry was engrossed by the documentary, too – even if he shrugs off the comparisons between Jordan and himself.

“It’s not me – that’s what a champion is, period,” he says. “If you want to win, you have to go through all of that. For me, that’s just normal – being demanding with yourself, being demanding with others. You have Michael Jordan, the best player in history, coming in early every day and working hard, and he’s more gifted than you. So as a team-mate, you’re going to come and not at least be at his level of work ethic? Otherwise, where are we going?

“Then, when the war is over, the soldier can cry. At the end of everything that Michael Jordan won, the players all wrote about what the team meant to them, then put pieces of paper on the fire. That was the very first time they saw him opening his heart – I thought, ‘Yes, because the war was finally over. He’s going to show you everything now, but not when he’s battling’.”

New York to Newport

To the outside world, Henry’s playing career seemed like plain sailing. He’s quick to remind FFT, however, that certainly wasn’t the case when we ask what it’s like to start again as a manager – slowly working his way up the mountain, having previously stood on the summit as a player.

“Nothing new,” he replies. “People always see the finished article, but don’t remember my struggle. In 1998, nobody thought I was going to be picked in France’s final World Cup squad. Then after I won the World Cup, I was the only player from that squad who didn’t have a pass from the manager – even if they weren’t playing well at their club, they would go to the national team.

“For a couple of years, I went to play for the under-21s. I didn’t fake any injuries, I didn’t say, ‘No, this is not my level’. I went to play. People don’t remember that. I didn’t start one qualifying game for Euro 2000. Nothing. I came back for the friendly just beforehand, made the squad, and then the rest is history. There was a lot of stuff like that.

“People often get confused about my time at Juventus – I was playing well there but left for different reasons, because of [managing director] Luciano Moggi. If you don’t respect me, I’m gone, and that’s what happened. At Arsenal, for the first few months I was on the bench behind Davor Suker, Nwankwo Kanu, Marc Overmars, Dennis Bergkamp... People remember the end, but I’ve had to battle in my life. No one ever gave me anything, and that’s how it should be.

“Now it’s the same as a coach. I keep on trying to say to people, ‘Hey, listen, I played but it’s over, done’. That part of me is dead. Now I need to do what I need to do to get better as a coach.”

That process began shortly after he had brought his playing career to an end at New York Red Bulls in December 2014. Just a few weeks later he was in Newport, commencing his coaching qualifications via the respected courses of the Welsh FA. Over the course of a year he completed the UEFA Pro Licence, studying alongside other well-known names.

“Mikel Arteta and Freddie Ljungberg were on my course,” he says. “Mark Kennedy, too – I don’t know if you will know the rest?”

Among them was Newport County gaffer Mike Flynn, who has spoken about the many WhatsApp messages he received from the French ace during the club’s run to the FA Cup fifth round in 2019.

“Yes, he was there too – oh, I didn’t know if you knew him!” says Henry, his face lighting up. “Joao Tralhao also, who I took to Monaco as an assistant. That was great fun. We were always challenging each other and we’re still in touch – we have a group where we speak to each other all the time. Flynny achieved something in the cup, while other guys have also been doing very well with Bala Town and other teams in Wales.”

Could he tell Arteta had a sharp football brain? “Yes, Mikel was a holding midfielder and the holding midfielder is always the guy that gels things together, with more of a view of shape,” explains Henry. “Didier Deschamps was the same, too. Then [for Arteta] going to Manchester City and working alongside Pep Guardiola, he must have learned a lot.

“I wish him all the best. You always need a bit of time. It was really impressive what he did in the FA Cup with Arsenal last season, outstanding. The FA Cup is so important for Arsenal – as you know, the record we have in that competition is second to none…”

Henry also coached at Arsenal for a period, working with the youth teams. Then came the chance to join Belgium’s coaching staff shortly after Euro 2016.

“That was a great experience for me,” he recalls. “Everything I learned from Roberto Martinez, Graeme Jones, Richard Evans and Inaki Bergara the goalkeeping coach was exceptional, because they’d been through it all, from Swansea and Wigan.

“People talk about playing with three at the back – when Antonio Conte arrived at Chelsea with a 3-4-3, people went, ‘Oh my God!’ But Roberto Martinez had done that with Wigan in 2011-12, and when they needed to stay up, too. They had nine games left and won seven of them. They played out from the back with Gary Caldwell and Emmerson Boyce – I’m not having a go at them, but I remember them with other managers, then I saw them playing for Roberto and suddenly they were passing the ball 50 times. They won the FA Cup like that, too. I know they scored from a corner, but they gave Man City a real game in that final.

“With the Belgium team, you’re going to win matches more often than not with that quality, and also the way he sets his team up. I learned a lot. Listen, if you’re not ready and you arrive and put on some passing drills, if you don’t impress Romelu Lukaku, Kevin De Bruyne, Eden Hazard, Mousa Dembele, Dries Mertens, Jan Vertonghen and Vincent Kompany – not only are those players not stupid, but they’ve also had great managers. If you do some drills, they could look at you and say, ‘What is this?’

“Mertens’ football IQ is beyond anything I’ve ever seen before. I remember being with Graeme Jones on the bench during a game – you can see that we’re going to be exposed on the counter and you get up to speak. Dries already saw it. His brain is way ahead of a lot of players I’ve seen in my life.”

Henry was part of Belgium’s journey to the semi-finals of the 2018 World Cup, where they lost to his home nation after a famous victory over Brazil.

“That was the first time for me to see the World Cup like that,” he says. “Before, I either supported France or played for France. Then I found myself working for another country, and I loved every minute of it. We finished third, and when we came back to Brussels, the amount of people there to welcome us… wow. The day we beat Brazil was one of the best moments of my life.”

Monaco: Les Miserables

That success in Russia just confirmed Henry’s desire to become a coach in his own right. Three months later, the opportunity came – at Monaco, the club where he’d commenced his playing career.

If it seemed like the perfect first job for the Frenchman, it didn’t turn out that way. Henry found himself at the right club, at the wrong time. Champions League semi-finalists in 2017, Monaco had sold Kylian Mbappe, Nabil Dirar, Bernardo Silva, Benjamin Mendy, Joao Moutinho, Thomas Lemar, Tiemoue Bakayoko and Fabinho by the time he returned to the Stade Louis II in October 2018.

The Monegasques had plunged to 18th in Ligue 1 at the start of the campaign, leading to the axing of Leonardo Jardim. If it seemed the only way was up, the reality was different. Henry could only pick up nine points from his first 11 league matches. His four Champions League fixtures delivered just a solitary draw with Club Brugge as Monaco finished bottom of their group.

In mid-January, hours after Mbappe had scored a treble in Paris Saint-Germain’s 9-0 rout of Guingamp, Henry’s 12th league game ended in a 5-1 home loss to Strasbourg. The club were 19th in Ligue 1, then lost at home to second-tier Metz in the Coupe de France. Henry was given the elbow, little more than three months after his arrival.

“We had 17 injured players, and 11 starters in those 17,” he reveals. “You’re trying to put something in progress, but I joined the club in October and didn’t even pass January. It’s very difficult to put something in place if you can’t carry on. Arteta had only one win in 10 [league] matches this season and he didn’t get the sack, because you need to trust the process. Arsenal trusted Arteta and rightly so, because he’s been trying to change stuff, to bring in players and play his way. Look at Ole Gunnar Solskjaer – people wanted him out, then he was top of the league. You need time to make it your team. It’s very difficult to analyse something and talk about what happened if you don’t get a chance.

“But I can only be thankful to Monaco for the opportunity they gave me. I’m upset at nobody – I still speak to the guys there. You know that in football, when you sign your contract as a coach, make sure the engine is still running – because the day afterwards, you might get the sack. I remember seeing [Manchester United assistant] Mike Phelan after I got the sack at Monaco – I went to see Arsenal vs United and he said, ‘Now I can say that you’re a coach!’”

Henry’s legendary status as a player in the principality was a millstone around his neck. From the moment he arrived, the eyes of the media were on him – other rookie managers wouldn’t be placed under the same scrutiny.

I know this is my path. I know it’s going to be bumpy, like my career was as a player. You either win or you learn – I always found out about myself in defeat rather than victory

Thierry Henry

“That’s something I have to live with,” he concedes. “If it’s good or bad, it’s going to be amplified, even if I don’t think it should be. I’m on my learning curve as a coach, but that’s how it’s always going to be.”

A chastening three months in charge of Valencia was enough to put Gary Neville off management, as he headed back to the Sky studio for good. Henry thought differently.

“You need to ask Gary why he didn’t go back into the game – that’s up to him – but nothing is easy,” he says, reflecting on the similarities of their first jobs in management. “People always jump to conclusions of, ‘Ah!’ But it wasn’t his team, and they weren’t his players or his style. When you arrive, it takes a little while to make it yours. I know this is my path. I know it’s going to be bumpy, like my career was as a player. You either win or you learn – I always found out about myself in defeat rather than victory. Some people are successful straight away, some aren’t. Mauricio Pochettino is a hell of a manager, but he only won his first trophy recently.

“Once, someone asked, ‘What’s success?’ It depends what the target was at the start. A lot of coaches have been successful but never won anything, then you have coaches that won stuff but never improved players. For me, it could be if you give a chance to a guy and they understand how to play. Let’s say they weren’t good on the ball, then two months later he pulls a ball down, he’s more composed, then he gets picked to play for the national team. That’s also success, because a coach has to make the players better – not only the team.”

Shut up and run

Ten months after departing Monaco, Henry moved to Montreal in November 2019. Asked how the move happened, he affords himself a wry smile.

“Well, I was available!” he says. “I knew MLS pretty well – I played there for four and a half years. Montreal is a fantastic town, a North American town with a massive European vibe. I thought it would be good for me, and a learning curve.”

That learning curve has involved adapting his style to a new generation of footballers. Many now respond better to the carrot, as opposed to the stick which inspired the pros he lined up alongside during the early days of his own career.

At Monaco, some said he was too abrasive. “Maybe Henry didn’t kill the role of the player inside of him,” suggested Russian midfielder Aleksandr Golovin. “Whenever things weren’t working out during training, he’d get nervous and yell a lot. Maybe that was unnecessary. He’d run out onto the field, start playing and show us some things. He’d scream, ‘Try to get the ball away from me’. He trusted younger players and I liked that, but there were times when he’d feel hurt and not speak to us. You could tell he didn’t fully transition into the role of manager.”

Henry also made headlines for an unusual incident after a press conference, pointedly staring at young defender Benoit Badiashile for not tucking a chair underneath the table before they departed the room.

This Thierry Henry moment! 🤨😅Two years to the day since he gave Benoit Badiashile the biggest glare you'll see 👀pic.twitter.com/g31CqtU59cDecember 11, 2020

“He would make examples of people and that annoyed a lot of people,” another player anonymously told Goal France. “He gave this haughty impression as if he wouldn’t consider anyone else’s opinion.”

Henry admits that he is adjusting his style as his career progresses. “I was educated in a certain way, but the new generation is now re-educating me,” he says. “What I knew for a fact and was sure about since I was young, it’s totally different today. You open a door for someone these days and it’s almost like you’re a king. I do it because I’m polite and that’s how it should be.

“Back in the days I played, whether it was right or wrong, if you didn’t play, then you had your answer. You don’t play, so figure it out. Now the coach has to come to you, explain why you didn’t play, but that you might play in two days. A coach is more of a philosopher now – a bad guy when you need to be a bad guy, but also your best friend. The psychology of the game has evolved a lot. You can never say to a player any more, ‘Shut up and run’. ‘Can I have an explanation?’ ‘No.’ The only explanation you needed back in the day was, ‘You’re not playing, so figure it out.’ You can’t do that now.

A coach is more of a philosopher now – a bad guy when you need to be a bad guy, but also your best friend

Thierry Henry

“You can’t stop players having their phones, either. The first thing they do now when they go back to the dressing room is check what’s been said on social media. I’m like, ‘Don’t you want to speak to your team-mates?’ But it is what it is – how are you going to battle with what’s happening in the world? Everyone is moving on.

“It’s a learning curve because I grew up with guys at Arsenal like Tony Adams and Martin Keown. If I didn’t understand, they weren’t going to talk to me, they were going to kick me, because that’s what I was going to get at the weekend.”

Henry pauses, warming to the theme.

“I was talking to a friend recently, saying that when I was a player, if you’d asked me if I was tired, I was always going to say no. ‘Are you OK?’ ‘Yes, I’m OK’. ‘Do you want to play?’ ‘Yes, I want to play.’ If they were going to take me out of the team, I was going to sulk because I wanted to play.

“If you ask me whether I was really tired, yes I was tired. Was I in pain? Yes, I was in pain. But you couldn’t say it – it was taboo. It was a ‘shut up and play’ era, where you said, ‘I’m not in pain’. ‘Are you sure Thierry, you’re limping?’ ‘Yes I know, that’s the way I walk’. You don’t want to say you’re in pain or you’re tired, because if a guy goes in front of you, you think, ‘I might not play again’. Now as a manager, I find myself saying, ‘Hey, you’ve played three games in a row, so maybe you need to rest’. The game has changed.”

During his time at Monaco, he also courted controversy for an incident in the heavy loss against Strasbourg. Frustration got the better of Henry, who was overheard on a pitchside microphone shouting, “your grandmother’s a whore!” at opposition player Kenny Lala.

“Too many times, we’ve seen his frustration on the bench,” his former Arsenal team-mate Emmanuel Petit said at the time. “When you are a player, you have the power to change what happens on the pitch. He’s still learning what it’s like to have some of his power taken away, and how to behave. His body language and communication need to improve if he’s to succeed as a coach.”

Henry apologised for the Lala incident and has since avoided similar controversy. That doesn’t mean he’s lost his passion, though – last year, cameras followed the Frenchman on the touchline during a MLS match against Nashville, and the footage went viral as he metaphorically kicked every ball, constantly shouting instructions at his players.

Henry’s approach is much removed from the quieter touchline presence of his former Gunners boss Arsene Wenger.

“You have to be you,” says Henry. “Arsene was a lot calmer – most of the time with him it was with the fourth official. Marcelo Bielsa sits down, but sometimes you see that Jurgen Klopp loses it. Antonio Conte shouts from the first minute to the last – whether his side are losing 20-0 or winning 20-0. Everyone was happy with him when he was winning games with Chelsea, then as soon as he started to lose, people were talking about him on the touchline, saying, ‘Ah, I think sometimes he should calm down’.

“If you just sit down and don’t do anything, people will go, ‘He’s not coaching, the team is suffering, why is he not getting up?’ Then if you coach your team, ‘Ah, that’s a bit much, sit down and let them play.’ If a guy sits, that doesn’t mean he’s not passionate, but this is me, I live the game. Be you. I’m a bit vocal at times – sometimes I shout too much, other times I don’t shout. That’s me.”

Thierry Henry was mic’d up during Montreal Impact’s recent game against Nashville 🎤 pic.twitter.com/vuHypC9K6COctober 28, 2020

He’s never tried to imitate Wenger, but he does talk to his old Arsenal manager and Pep Guardiola, his coach at Barcelona.

“Whenever I see a coach, I always speak to them,” says Henry. “Obviously I speak to Pep, and I speak to Arsene whenever I can reach him. We speak, because when I was a player and he was a coach, I was chewing his ear out. Now as a coach I want to know things.”

What did he learn from Arsene and Pep in those storied playing days?

“Arsene triggered my brain – I needed that at the time,” he says.

“I needed to be more confident, to realise what type of player I was and what I could do. I started to ask myself the right questions. I always blamed others, but I began to blame myself first. I started to see how I could help others instead of saying to others, ‘Hey, you need to help me’.

“Pep was a master of tactics. He can see so much that sometimes it might be a problem for him, because he sees a lot and he wants to change things a lot! Tactically, he’s a freak. The stuff I learned from him was incredible.”

Utopia with Lionel Richie

Back in February 2020, in Henry’s first two matches as manager, Montreal edged past Costa Rican side Saprissa in the CONCACAF Champions League, then overcame New England Revolution in his debut MLS fixture. Former Barcelona team-mate Bojan Krkic featured in that game – days later, ex-Spurs midfielder Victor Wanyama arrived.

But soon, the coronavirus shutdown took the whole world by surprise. When the MLS Is Back competition began four months later, Montreal won just one of their four fixtures following disrupted preparations – Canada’s more cautious approach to the pandemic meant Montreal had been among the last MLS sides given permission to restart training by local health authorities.

After the regular campaign resumed, the team returned to play three home games in Montreal, before travel restrictions between Canada and the US forced a relocation to the Red Bull Arena – Henry’s former home with New York Red Bulls – for the remainder of the season. By the end of the campaign, they had won eight games and lost 13 – scoring freely but conceding the most goals in the Eastern Conference – to finish ninth out of 14 teams and equal their position in 2019.

Under the Frenchman, a newly expanded MLS play-off format meant Montreal did at least feature in the end-of-season knockout event for the first time since 2016, Didier Drogba’s second and final year at the club. This time, they fell at the first hurdle, losing at New England Revolution – the team they had beaten on the opening day of the season in February. An immediate exit also followed in the resumed Champions League, against Honduran side Olimpia on away goals.

“The aim of the season was to qualify for the play-offs and build an identity,” explains Henry. “We reached the play-offs, but it was really difficult – I think it brought the team together on a human level. The players had to play in New Jersey and didn’t see their family for a very long time – you lose a game and return to your hotel room. I learned a lot about the human touch you need.

“But the year wasn’t perfect. We wanted to play out from the back and we made a lot of mistakes during that process, because you’re deprogramming players to reprogramme them, and they need to feel confident about that. When I went to Barcelona, it took me a year to understand what they wanted, and I wasn’t dumb.

“I don’t ask anybody to do something they can’t do – you’ll never hear me tell a guy to take the ball and dribble past five players. It’s a team effort – space, structure, positioning, understanding the ball travels faster than the player. You have to respect the philosophy and you have to fight, then everything after that is excusable.

“If you don’t fight, you don’t respect what we said we were going to do, you’re late or you don’t train hard, then no, that’s not on. That for me is unacceptable, and my players have always known that. But if you come up against a better team and make a mistake, OK – everyone makes mistakes.”

As the 2021 campaign approached, things remained complicated. After a long delay, the MLS start date was finally set for April 3, then pushed back to April 17 – hampering attempts to organise a pre-season training schedule, amid continuing uncertainty about Montreal’s home venue.

In the end, with Montreal looking set to relocate to the US again, Henry had to take a very tough decision – the decision to walk away from the job in late February.

Days earlier, he’d seemed close to moving to Championship outfit Bournemouth – the Dorset side were reportedly set to approach Montreal, seeking permission to talk to Henry. It looked like he would get the job, only for the Cherries to do a U-turn – after a mixed reaction from fans, they announced that Jonathan Woodgate would remain in charge for the rest of the season.

Denied the perfect exit strategy, Henry decided he still had to step down as boss of Montreal. “The last year has been extremely difficult for me,” he said. “Because of the pandemic, I was unable to see my children. Due to the ongoing restrictions and the fact that we will have to relocate to the US again for several months, 2021 will be no different. The separation is too big a strain for me and my kids. It is with much sadness that I must return to London and leave Montreal.”

He made the decision knowing that it left his managerial career in limbo.

Ever since Henry moved into management, many have been watching on, wondering if he has what it takes to become Arsenal boss one day. The Frenchman has a long way to go to reach that level, but does it remain an ambition, even a dream?

“Listen, if you ask an Arsenal fan if they’d like to coach Arsenal one day, they’ll say yes,” admits Henry. “If you ask an Arsenal fan if they’d like to score a goal for Arsenal, they’ll say yes. When I speak about it, it’s a utopia. People get carried away whenever I say that it’s my club, but I have it in my blood – I’m an Arsenal fan. So if you’re asking me if one day I’d like to coach Arsenal, then yes. If you ask if one day I’d like to be Arsenal’s kit man, then yes. If you ask if one day I’d like to cut the grass at the Emirates Stadium, then yes.”

Listen, if you ask an Arsenal fan if they’d like to coach Arsenal one day, they’ll say yes. If you ask an Arsenal fan if they’d like to score a goal for Arsenal, they’ll say yes. When I speak about it, it’s a utopia

Thierry Henry

Henry stops just short of volunteering to be Gunnersaurus. “But it’s a utopia, and I am far from that. If you ask me am I dreaming, yes I’m dreaming. But when you’re not dreaming, you’re awake and there is a reality. Would I love to coach Arsenal? Yes. Would I love to go to Barcelona? Yes. Would I like to play for Arsenal again? I’d love to play for them again, but the reality is I can’t!

“I’m on my learning curve, I want to do well for the team I’m coaching, then time will tell. If you’re not successful, you’re not going to have those types of opportunities. I’m just concentrating on what I can control, and the rest is a massive utopia. Would I have liked to sing like Lionel Richie? Yes, but I don’t sing like Lionel Richie!”

Henry bursts into laughter again, before returning to make a serious point.

“Arsenal is part of me and always will be – half of my heart belongs to Arsenal, and the other half to my family,” he continues. “The understanding I have with Arsenal fans is something I cannot describe – it’s something I’m always going to miss. If I could relive one night, it would be when I came back on loan and scored the winning goal against Leeds. It was the third round of the FA Cup, Leeds were in the Championship at the time and it wasn’t the best goal ever, but I reconnected with the fans for one night... one more night. That was priceless.”

Right now, more nights like that as a coach seem like a long shot, but Henry will not give up – neither on his Arsenal dream, nor on becoming a successful manager.

It remains to be seen what path he takes from here. When he takes his next job, he will remember those words from Wenger. Enjoy the ride and all the best, Thierry. Because it’s not easy.

NOW READ

FEATURE Is blunder-prone Granit Xhaka partly a product of Arsenal's environment under Mikel Arteta?

QUIZ Can you name every club Thierry Henry scored against for Arsenal?

SOCIAL What's the funniest thing that's ever happened in football? We asked FFT followers for their answers

Chris joined FourFourTwo in 2015 and has reported from 20 countries, in places as varied as Jerusalem and the Arctic Circle. He's interviewed Pele, Zlatan and Santa Claus (it's a long story), as well as covering the World Cup, Euro 2020 and the Clasico. He previously spent 10 years as a newspaper journalist, and completed the 92 in 2017.