Arsenal will continue to start behind – and Arsene Wenger has lost his disciples for it

The Arsenal boss is driven by principle rather than stubbornness but, as Alex Hess explains, it's done him no favours with the Gunners' fanbase

Arsene Wenger is a man who likes to defy common logic, so it’s apt that just one match into the new season, his side have already continued a pattern which spans numerous games. Inept, injury-ravaged and ill-prepared: Sunday’s loss to Liverpool may be Arsenal’s only fixture so far this term, but it was anything but an isolated event.

Half a decade ago, Arsenal followed up a miserable opening-day draw at St James’ Park with a home defeat by Kenny Dalglish’s Liverpool, Ignasi Miquel and Carl Jenkinson both making their league debuts, and Emmanuel Frimpong handed a first start (and duly being sent off). The following game took them to Old Trafford, and the 8-2 evisceration that followed – this time featuring Armand Traore at left-back and a very much out-of-favour Francis Coquelin – prompts Vietnam-style flashbacks among Arsenal supporters to this day.

The following season’s opening fixtures brought two points and zero goals from two eminently winnable opponents in Sunderland and Stoke, while 2013/14 saw Arsenal kick off with a 3-1 home loss to Aston Villa, their (at this point) sole summer signing Yaya Sanogo not deemed worthy of a cameo.

A year later, an injury-time winner snatched the barely deserved points off Crystal Palace, but one win from their next seven left Arsenal 11 points off the top before the clocks went back. Last year it was West Ham who assumed host-slaying duties at the Emirates’ curtain-raiser, Arsenal having used the summer to add not a single outfield player to their squad.

History repeats itself

Alex Iwobi – a player who’s completed 90 minutes once in the league – was anonymous on the wing, while Alexis Sanchez, a winger, scampered about up front to similar effect

In light of all this, Liverpool’s surprise rout last weekend was in fact nothing of the sort. A surprise, after all, should have little in the way of precedent; Sunday’s result was practically signposted.

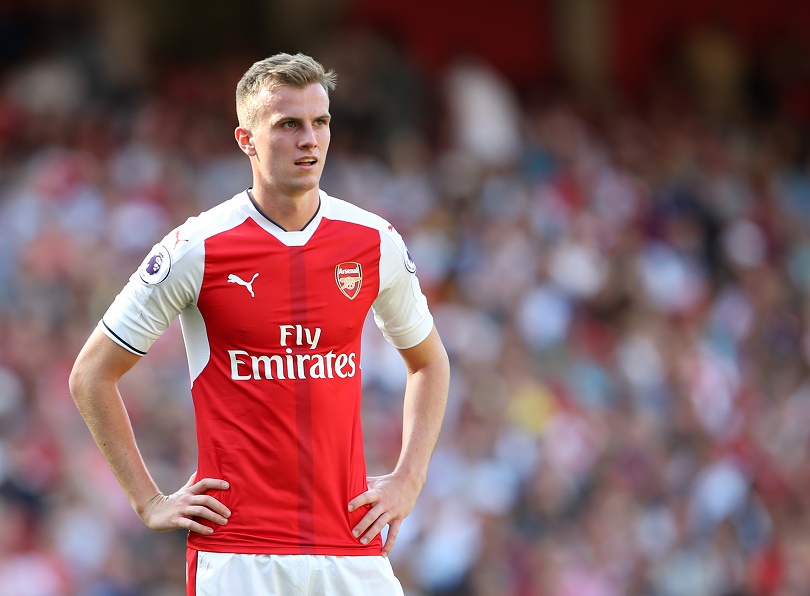

The usual motifs were all in place: the raw centre-back given the debut from hell; the bench lacking a game-changing goal threat; the summer’s worth of underwhelming transfer dealings congealing into a faintly mutinous atmosphere; the drone of boos that met the final whistle.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Wenger may currently be facing issues out of his control – injuries being one (though their regularity is alarming) – but he's far from a victim of circumstance. He's known for a fortnight, for instance, that Per Mertesacker wouldn’t be available, and his non-selections of Laurent Koscielny and Olivier Giroud were wholly self-enforced. And yet he still went into a game against likely top-four rivals with a 20-year-old – one with just 26 second-tier starts to his name – in the heart of the backline.

Sadio Mane takes advantage of some kind defending

At the other end of the pitch, Alex Iwobi – a player who has completed 90 minutes once in the league – was anonymous on the wing, while Alexis Sanchez, a winger, scampered about up front to similar effect.

“The last four years we have been fourth, third and second, and we want to make progress again,” Wenger said pre-match – but the XI he sent out had as much the look of champions as Jean-Claude Van Damme resembles an Oscar winner. What is it with Arsenal and slow starts?

Non-negotiable principles

Wenger’s reluctance to abandon his methods doesn’t stem from a selfish desire to be proven right, but from his unwavering belief in a set of principles

At this stage, there's one accusation that prevails above all others; a Google search for “Arsene Wenger stubborn” returns over 77,000 results. The argument runs that Wenger, eternal believer in youth development, patient coaching and unearthing value in a cash-flooded market, spends every summer steadfastly refusing to compromise those beliefs, regardless of the rewards. He does so in the face of all reason, and to the manifest detriment of his club. Quite simply, he’s far too stubborn.

But perhaps a fairer characterisation than stubbornness would be idealism: Wenger’s reluctance to abandon his methods doesn’t stem from a selfish desire to be proven right, but from his unwavering belief in a set of principles: ones, it should be said, that most of his fans share even if many would happily sideline them in exchange for a league title or two. But idealism by its very nature knows no compromise: hence why his side lined up with Rob Holding and Iwobi on Sunday and not, say, Jose Fonte and Romelu Lukaku. The difference between stubbornness and idealism may seem like pointless semantics, but there’s an important distinction.

Which isn’t to say that Wenger’s not prone to mischaracterisations of his own. Generally speaking, he interprets his fans’ frustrations as the blinkered craving for novelty instilled by the fast-food culture of a world gone to the dogs. “If you want to make everybody happy, then just buy 20 new players and everybody is full of hope,” he said last week. “It is very difficult in the modern game. There is always demand for new – but new is just new. After six months it’s not new anymore.”

To Wenger, those jeering him from the cheap seats, clutching signs demanding he “Spend spend spend”, are simply a sad indictment modern football’s fetishisation of wealth, hysterical cash-obsessives driven by an irrational desire to match their sugar-daddied rivals pound for pound.

Cynics and critics

The point of all this is not that Wenger is necessarily right or wrong, but that his idealism is having the opposite effect to what you’d expect

But most of his critics would describe their frustrations not as stemming from Wenger’s reluctance to exchange the GDP of a banana republic for the planet’s best players, but simply from the fact that progress appears so achievable if only he would make the odd compromise – ones which are well within his club’s capability. It’s tempting to conclude that the truth lies somewhere in between, but in fact it probably lies a lot closer to the latter view than Wenger’s own.

The point of all this is not that Wenger is necessarily right or wrong, but that his idealism is having the opposite effect to what you’d expect. Idealists, typically speaking, are inspirational people; those who fill their disciples with hope and optimism and faith, however unrealistic their masterplan may actually be. Leon Trotsky, Jeremy Corbyn, Spartacus, Dr Evil: all different breeds of crusader, but all united in their ability to inspire a band of dedicated and undying loyalists.

In the cynical, mercenary world of modern football, with public alienation an epidemic, you’d think that effect would be multiplied: that a man who believes in something beyond money, medals and corporate-sponsored hashtags would exhilarate and inspire. Yet Wenger seems to have fostered the opposite: a band of cynics overly keen to jump on his every mistake, to see each point dropped as catastrophic and to wilfully read every deficiency of Arsenal’s as a personal failing of the Frenchman's.

Start of season woes

Which brings us back to the start of the season, and Arsenal’s repeated failings every time autumn dawns. For the typical football fan this is the annual period of hope and excitement, the moment to dream freely before fantasy's infinite possibilities are bludgeoned into submission by the harsh truncheon of reality. Speak to fans across the country at the start of August and the prevailing mood will always be one of wide-eyed anticipation; of glorious, foolish naiveté.

At Arsenal, though, it’s come to be a time of angst, misery and exasperation: a summer's worries cruelly vindicated as early ground is lost to rivals and the club’s 10-month orbit of fourth place recommences. Arsenal fans, forever in the Champions League yet forever unhappy with their lot, are often criticised for being unappreciative. But their real problem isn't a brattish intolerance of not finishing first, it's that actually doing so has come to seem implausible. The element of fantasy has been lost.

What unites the great idealists, whether or not they succeed in their cause, is that they succeed in igniting their followers' imaginations. Defying common logic as ever, Wenger is a great idealist who is doing precisely the opposite.