Arsene Wenger’s major flaw – and why it impacts Arsenal now more than ever

Twenty years ago, a change of plan helped Arsenal win the Premier League – but it also revealed a great manager’s long-standing weakness, says Chas Newkey-Burden

Ian Wright appeared at the dressing room window, dressed just in his underpants, and swapped insults with Arsenal fans. As tempers rose, an onlooking policeman grabbed his radio and barked: “Haul Ian Wright out of the dressing room. I want to talk to him – now!”

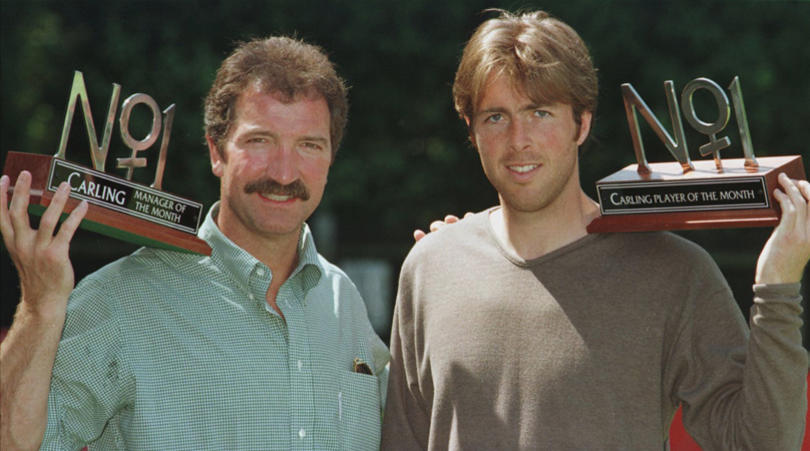

It was December 1997, five months into Arsene Wenger’s first full season at the club. After a 12-match unbeaten run, the Gunners had lost four games out of six – including a 3-0 reverse at Derby – and, on this fateful day, a 3-1 defeat to Blackburn. It left the club in fifth place, 10 points adrift of leaders Manchester United.

At the final whistle, before Wright’s panted ranting, Gunners fans had booed and thrown their scarves onto the pitch. The season was unravelling. The librarians were revolting. Something had to give – and it did.

Pointed fingers

The players called a clear-the-air meeting at the Sopwell House hotel in St Albans. Home truths were aired and fingers were pointed, never with more sharpness than when the back four demanded that central midfielders Patrick Vieira and Emmanuel Petit focus more on the defensive side of their duties. “You haven’t got a clue what your job is,” Tony Adams told them. “We need some protection.”

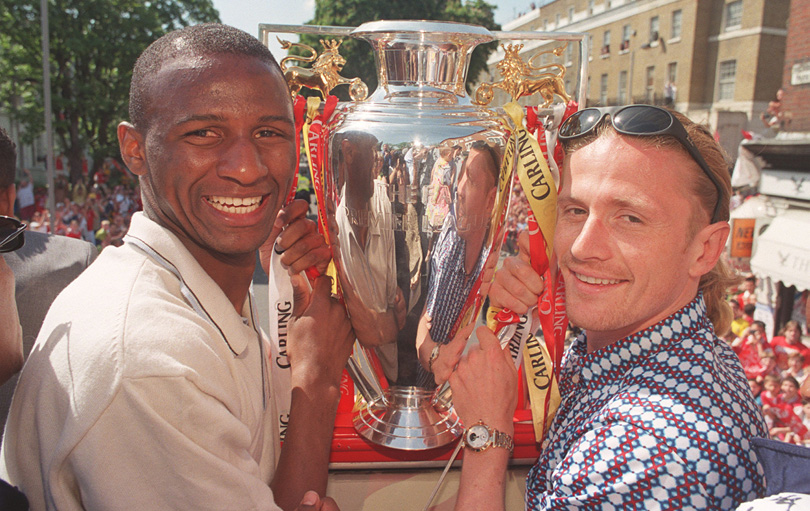

The Gallic duo responded positively and this simple tactical tweak changed everything: the team went on an 18-match unbeaten league run, lifting the title for the first time in seven years.

But why did it take Adams and his fellow defenders to identify such an obvious problem and to point out the simple solution? Isn’t that what the manager is there for?

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Critics of Wenger say this episode was the merely the first signal of a permanent weakness in his managerial philosophy; a laissez faire approach that largely delegates tactics and coaching to the players.

First impressions

When he first arrived in north London, back when the media sat adoringly at his lotus feet as if taking instruction from a Vedic sage, Wenger explained his philosophy was that a coach should simply provide a framework in which players can express themselves.

He has been true to his word: by all accounts, the boss says little to his players in the dressing room. Even at half time, Wenger largely eschews tactical switches from opposition to opposition, and almost never raises his voice. Instead, he simply encourages his players to be themselves and have faith that this credo will guide them to glory.

For Jose Mourinho and Pep Guardiola, it becomes like a game of chess. But Wenger is still all about purist expression

But other managers are increasingly obsessing over tactics. Should their team drop off, press high, counter-attack or opt for a possession-heavy approach? These bosses make tweaks throughout games. For some, like Jose Mourinho and Pep Guardiola, it becomes like a game of chess. But Wenger is still all about purist expression.

Even for the biggest game of his career, he stuck to his guns. In his biography of Thierry Henry, Philippe Auclair says that a couple of days before the 2006 Champions League Final, Wenger “casually” mentioned that he and his coaching staff would wait until the eve of the game before taking a look at how Barcelona generally lined up and played. Henry himself has expressed surprise at how briefly Wenger dwelt on the opposition in his talk ahead of the historic match.

Deviations from this approach are noteworthy because they are so rare. The 2005 FA Cup Final, when he packed the midfield and encouraged a parked-bus strategy; the switch to a 3-4-2-1 formation during last season’s run-in; and his rousing pre-match team-talk, which he delivered on the brink of tears, at May’s FA Cup final against Chelsea.

Otherwise, he has seemingly preferred to keep his hands off. The trouble is that the success of this sort of philosophy depends on the intelligence and character of his players at any given time.

Change in personnel

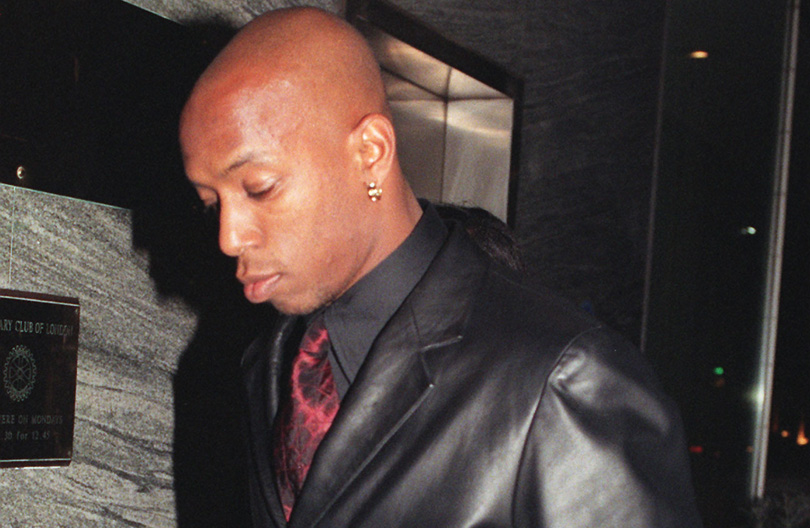

It worked well when his teams boasted players with the astuteness and stature of Dennis Bergkamp, Tony Adams, Patrick Vieira and Robert Pires. As Sol Campbell put it: “When I was there we used to police it ourselves. We had the characters to police it ourselves.”

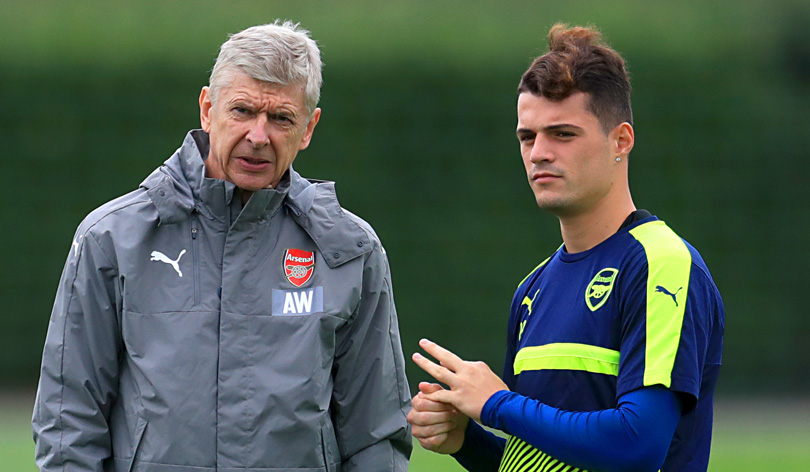

But Wenger’s squads in the Emirates era - featuring less cerebral creatures such as Nicklas Bendtner, Olivier Giroud, Alexis Sanchez and Granit Xhaka - clearly struggle with the hands-off approach. It’s as if they are crying out for leadership and direction.

Recently, during an illuminating interview with the Gooner Ramble Girls podcast, Lee Dixon shone a light on this Wenger weakness. It is worth noting that, unlike some Arsenal legends who have become droning bores, forever hissing against the manager under whom they enjoyed such success, Dixon is bright as a button and painstakingly fair.

Which is why his words about Wenger are so damning. “He doesn’t teach you what to do, he just expects you to go out and learn off the players around you,” he began.

For example, he remembered that Ashley Cole “couldn’t defend to save his life” when he was first breaking through at Highbury – he only became the greatest left-back in the world after Tony Adams taught him how to defend. “Arsene looked at it and thought: ‘Brilliant, Tony’s doing my job for me,’” said Dixon.

But is there anyone in the current Arsenal squad able to do Wenger’s job for him with the likes of Alex Iwobi, Rob Holding and Reiss Nelson? Is the boss’s approach to blame for the stunted development of Jack Wilshere, Calum Chambers, Theo Walcott and the departed Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain?

Quite possibly if you listen to Dixon, who was 32, with two league titles and a Cup Winner’s Cup under his belt, when the Frenchman arrived at the club.

“I loved playing for Wenger,” he said. “But I don’t think I’d have loved playing for him when I was 18. Because he wouldn’t have taught me anything.”

As the nights draw in and Halloween approaches, these words will send a chill down every Arsenal fan’s spine.