Arsene Wenger’s unlikely legacy: a new era of austerity for struggling Arsenal

Cautious frugality was a source of immense frustration for fans under their long-serving Frenchman – but where has it got them?

It felt like an indictment of management’s finest businessman. The great economist may have got the sums wrong. His successor sounded broke. “We cannot sign permanently,” said Unai Emery last week. “We can only loan players.”

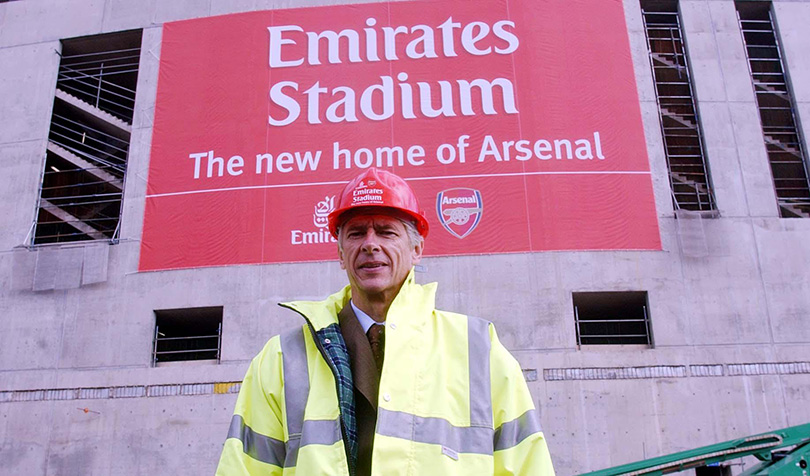

Arsene Wenger’s achievements included allowing Arsenal to pay back most of the debt incurred when building the Emirates Stadium. Now they may be forced to become a different type of borrower.

Wenger felt like football’s ultimate miser, guarding Arsenal’s money with Scrooge-like determination when supporters urged him to spend in short-term quests for success. Now his legacy looks doubly unwanted, with the north Londoners allegedly strapped for cash and outside the Champions League cartel. It sounds strange, given Wenger’s command of the figures, but Arsenal’s numbers are not adding up anymore.

Wasteful

They are not a byword for fiscal prudence now; nor, indeed, do they seem to be manning the barricades in defence of sanity against the increasingly mad world of football finances. Not when they are paying Mesut Ozil the Premier League’s second-biggest salary and he couldn’t even make the bench at West Ham last week. Some £18 million a year goes to a man outside the matchday 18; it is the definition of wastefulness.

Meanwhile, Arsenal, who once sat on a mountain of cash reserves approaching £200 million, now look relative paupers and Emery’s slender budget may be stretched further by the need to replace three departures on free transfers in the summer: the retiring Petr Cech, and out-of-contract duo Danny Welbeck and Aaron Ramsey.

Wenger was more risk-averse than most, but business planning in football feels inherently precarious. Arsenal’s economic model was predicated on Champions League qualification; now they may be denied the competition’s considerable revenues for three consecutive seasons. Had Wenger left two years earlier, their income stream from Europe would have been bigger.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

And yet Arsenal’s plight is certainly not entirely his fault. The suggestions that Sven Mislintat is going will leave the club’s transfer strategy in ruins after some £130 million that Wenger helped generate was spent (and Henrikh Mkhitaryan and Stephan Lichtsteiner also acquired) during the German’s brief reign as head of recruitment.

Meanwhile, Wenger used to bemoan “financial doping”, and Saturday brings a contrast between Roman Abramovich – who pumped another £69 million of his money into Chelsea over the last financial year, meaning the club's debt to him now stands at £1.13 billion – and Stan Kroenke, who displays no such largesse. Wenger’s former sidekick, Ivan Gazidis, reportedly landed himself a £1 million pay rise when he became Milan’s CEO. It indicated a skill at negotiating that was sadly less apparent with players; this particular Ivan may have been terrible at concluding their contract talks at a suitably early stage.

Free failing

Because while all clubs lose some money on out-of-contract footballers, Arsenal’s balance sheet has suffered particular losses. Samir Nasri, Robin van Persie, Gael Clichy and Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain were sold after entering the last year of their contracts, Alexis Sanchez swapped in the final six months of his. Arguably, Arsenal got the true market value of none.

Since 2013 alone, they have lost the retiring Per Mertesacker, plus Jack Wilshere, Santi Cazorla, Mathieu Debuchy, Tomas Rosicky, Abou Diaby, Nicklas Bendtner, Bacary Sagna, Andre Santos, Andrei Arshavin and Denilson on free transfers. Some were misfits; some, like the luckless Cazorla, the victims of misfortune; some ageing; some overstaying their welcome when Wenger’s loyalty proved misplaced. But the reality is that they cost the best part of £100 million and left for nothing.

In the process, Arsenal have recouped the least money among top-six clubs in the transfer market since 2015. It may explain why they perhaps failed to future-proof the squad.

The defence is too old, and while the £35 million Shkodran Mustafi should have been its cornerstone, he is not. Too much of their resources are concentrated on one position: their two biggest buys, Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang and Alexandre Lacazette, are both strikers. Too much of the money has gone to Ozil: Wenger had to be persuaded by the club to spend £42.4 million on him, and while he described the German’s £350,000-a-week deal as the “cheapest option” last year, his influence was fading by then. It is hard to escape the sense that it jarred with him.

Now the question with Ramsey is whether the false economy would have been giving him a huge pay rise or losing him on a free transfer. Either way, Arsenal were guaranteed to pay a price.

Always uphill

They often have. Circumstances have destroyed financial models. “Outside resources,” as Wenger termed investors like Abramovich and Sheikh Mansour, rendered it harder for Arsenal to compete for titles while paying for a ground.

When Arsenal’s self-generated resources were at their most stretched, they pioneered a quasi-socialist scheme among superclubs with a lower maximum wage and more equality in salaries. Unfortunately, that meant Robin van Persie and Cesc Fabregas didn’t earn dramatically more than the underachievers, and their underpaid best players started to be picked off by their peers while their overpaid worst attracted fewer offers.

Yet when Arsenal didn’t spend more recently, it was through choice, not necessity; a product of Wenger’s obstinate faith in the players he possessed rather than a chastening realisation he could not afford replacements.

But if that fiscal caution enabled the Frenchman to balance books during his 22-year reign, such a juggling act looks harder for the beleaguered Emery. If Sir Alex Ferguson bequeathed Manchester United a situation where his successors could spend vast sums every summer, Wenger’s legacy seems to include more austerity.

And hardship makes Emery’s job all the tougher.

Richard Jolly also writes for the National, the Guardian, the Observer, the Straits Times, the Independent, Sporting Life, Football 365 and the Blizzard. He has written for the FourFourTwo website since 2018 and for the magazine in the 1990s and the 2020s, but not in between. He has covered 1500+ games and remembers a disturbing number of the 0-0 draws.