Back the juggler? How Michael Knighton wowed the Old Trafford crowd, but not the boardroom

Many Manchester United fans are unhappy with the current ownership structure of their club, but things could have been very different had infamous property magnate Michael Knighton been able to complete his buy-out of the club 25 years ago. Andy Mitten tells the tale of the deal that never was...

Saturday August 19, 1989. It’s an hour before kick-off and Manchester United are about to start the new season with a home game against champions Arsenal, but the only thing on the mind of United’s long-serving kitman, a Gorse Hill born and bred former taxi driver named Norman Davies, is finding a strip for United’s new chairman-elect Michael Knighton.

In rare Mancunian sunshine, 47,000 watched as Knighton ran onto the pitch wearing boots and a United training top, before juggling a ball in front of an ecstatic Stretford End, who went home even happier after United's 4-1 victory.

United’s supporters were so thrilled because Knighton, a charismatic property speculator, had come in with an offer to buy out the unpopular then chairman Martin Edwards, and the promise of pumping enormous sums of money into rebuilding parts of the stadium.

You can't please everyone

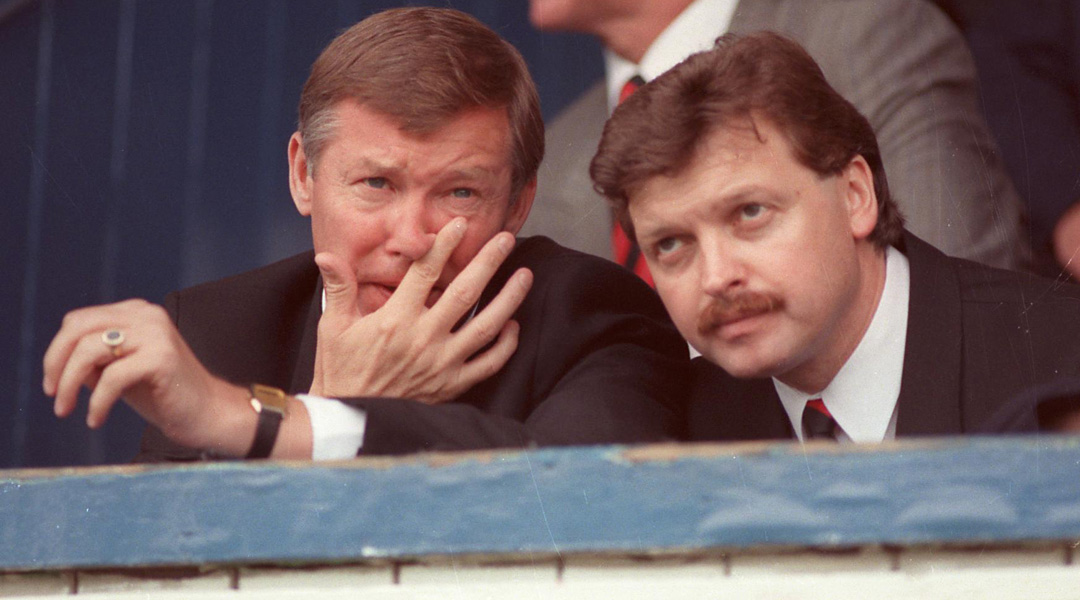

Knighton’s performance did not generate the same response elsewhere. As he watched Knighton on a monitor from his office alongside Arsenal manager George Graham, Alex Ferguson had a bad gut feeling about this publicity stunt from a man who had yet to conclude any deal. The mood was far worse in the directors’ box.

“I was horrified,” admits Martin Edwards. “Absolutely horrified. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. I kept saying to myself, ‘What the hell have I done?’ I realised that I’d made a big mistake. The other directors felt the same. They cringed and began to turn on Knighton."

Many still find it hard to believe that Edwards seriously contemplated the sale of one of football’s prime assets, but he still maintains it made perfect sense. There were serious problems at Old Trafford; the 47,000 gate that day was almost 10,000 over the average crowd from the previous season, and a figure which would not be bettered for over a year.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

United’s average attendance had slipped below Liverpool’s the previous season as the club finished 11th in the First Division. The average was 38,000, but crowds as low as 23,368, 26,722 and 30,379 had watched United’s three final league games of the season against Wimbledon, Everton and Newcastle. The club took just one coach of travelling fans from Manchester to a league game at Queens Park Rangers, witnessed by a paltry 10,017.

Edwards told his under-fire manager Alex Ferguson that he was going to sell the club, saying: “If you know anyone who would be prepared to buy my shares for £10 million, with a guarantee that he will spend a further £10 million on renewing the Stretford End, then he can have it.”

Ferguson, who enjoyed a good relationship with his chairman, asked him why he wanted to sell, and concluded that Edwards felt he could never win the fans over and had no other way out. Michael Knighton appeared as a potential purchaser of United that summer.

A different economic climate

“I wanted to sell the club to Michael Knighton for two reasons,” Edwards explains to FourFourTwo at his home in Wilmslow, Cheshire. “I had a huge debt to the bank, almost a million pounds. Since a rights issue in 1978, I’d put over £400,000 of my own money into the club. My house was the security against that debt. I couldn’t go on feeding that debt forever and I wasn’t comfortable. This was pre-Sky television, when the economic climate was very different in football.

“The second reason was that the Stretford End needed rebuilding and the price would have been around £7 million. I didn’t have the money. Something would have had to give. Michael Knighton arrived out of the blue and was prepared to give me £10 million, which was more than what my shares were worth. He also said that he was going to rebuild the Stretford End and would spend a further £10 million on that. It solved both my problems. And there’s another thing – what if I had turned him down and it became public knowledge that I had turned down the money which would have rebuilt the Stretford End? In hindsight, it sounds ridiculous given the wealth of the club today, but at the time it wasn’t a bad offer.”

Edwards’ first impression of Knighton was positive. “Michael Knighton is a very interesting guy when you first meet him,” he explains. “I thought he was serious, ambitious and I knew that he had backing from two very wealthy partners.”

Although later portrayed as a maverick fantasist, Knighton correctly identified the huge potential in United. He said that the club had a major pulling power which had not been exploited. He predicted that it would become a £150 million business within 15 years. (Within 11 years United were valued at over £1 billion). He commissioned a study which identified several areas for development at Old Trafford such as television rights, merchandise, a magazine and a hotel – all of which were exploited in later years.

With the club sale set to go through, Edwards relaxed and a previously parsimonious United spent heavily on Neil Webb, Mike Phelan, Gary Pallister, Paul Ince and Danny Wallace. There was much optimism among red ranks, and Knighton’s juggling act on the pitch was taken to show that he had a genuine love for United, projecting an enthusiasm and a warmth that the reserved Edwards rarely evinced.

But now the directors began looking for loopholes to get out of the deal. Edwards is quick to point out that this wasn’t purely motivated by their reaction to Knighton’s tomfoolery. “Of course, there was an element of self interest to them, as they wouldn’t have gained from Knighton coming in,” he says.

A swift exit

Ultimately, Knighton didn’t have the money to take over. Again, Edwards counters the widely held belief that Knighton had a made a fool of the United board.

“He’d proved that he had the financial backing, but then he fell out with the other two partners because they would have side-lined him eventually,” says Edwards. “Knighton realised what was going on and he wanted to be number one. The backers pulled away. When the pressure came on, Knighton couldn’t deliver the money.”

Knighton exited, Edwards stayed. Just over a decade later, Edwards would sell his United shares for £85 million.

Knighton wasn’t the first outsider with whom Edwards had negotiated about selling Manchester United. The controversial publisher and Daily Mirror owner Robert Maxwell had boasted about buying the club in 1984. A rampant egomaniac, Maxwell already owned Third Division Oxford United, but they were a long way from the perceived glamour of the top flight.

“I was never close to doing a deal with Robert Maxwell,” Edwards insists. “He approached me. He was a really big noise at the time. I agreed to a meeting with him, only because Roland Smith was involved in the deal. He had been on the board with my father Louis Edwards and was his friend. He wanted me to meet Maxwell. I agreed, but as far as I was concerned, it was private. What did Maxwell do? He announced to the world that there would be talks about him buying Manchester United.”

Edwards met Maxwell at his London office, Maxwell House.

“We had little common ground,” he recalls, “and I didn’t particularly like him. I felt that he was trying to get United on the cheap and we were miles apart. When I was leaving, he said, ‘We’ll do a joint press release.’ I got in the car back to Manchester, when I received a call from Maurice Watkins, (the club solicitor and director) who was at the meeting. Maurice said, ‘Maxwell has issued a press release.’ It was very one-sided, covering himself and against me.”

Edwards was strongly criticised by fans. “I look back now and I realise one thing,” he says, “I never won the PR battles. I didn’t win it with Maxwell and I didn’t win it with Knighton, did I? I was never interested in public relations and I’m still not. I’m disappointed in the modern world in the sense that people like Tony Blair and [Gordon] Brown, it’s all about image and PR. Where’s the substance? Did Winston Churchill need a PR man? No. If I had to make a statement then I made it personally to the press.”

Aliens, Frankenstein, God and Jimmy Glass

Other United chiefs felt the same. "The Knighton affair was a worrying time," said long time director Maurice Watkins, when asked to name a low point in his time at the club. "I liked Michael, but there was a danger that the club would go a different way."

Knighton ended up at Carlisle United and told fans that they would compete in one of the best stadiums in Europe. As anyone who has been to Brunton Park will attest, it didn't quite happen, but he had his moments and retained his eccentric reputation.

“I believe in alien beings. I believe in Frankenstein. I believe in God,” said Knighton after Carlisle goalkeeper Jimmy Glass had kept the club in the Football League with a late goal. “And most of all I believe in on-loan goalkeepers who can score goals in the 91st minute.”

But to this 15-year old fan stood on the Stretford End (right side), Knighton was the most exciting thing to happen at Old Trafford in a while. I applauded like the rest of the fans around me, sang 'Fergie, sign him on' and really did think that a new messiah had arrived.

A United messiah finally did start to bear riches at the end of that same season, but his name was Ferguson, not Knighton.

Andy Mitten is Editor at Large of FourFourTwo, interviewing the likes of Lionel Messi, Eric Cantona, Sir Alex Ferguson and Diego Maradona for the magazine. He also founded and is editor of United We Stand, the Manchester United fanzine, and contributes to a number of publications, including GQ, the BBC and The Athletic.