Barcelona's irresistible attack excels in the one area Bayern Munich's fails miserably

Michael Cox says Pep's German champions lack the fearsome dribbling that saw them dismantle the Catalans in 2013...

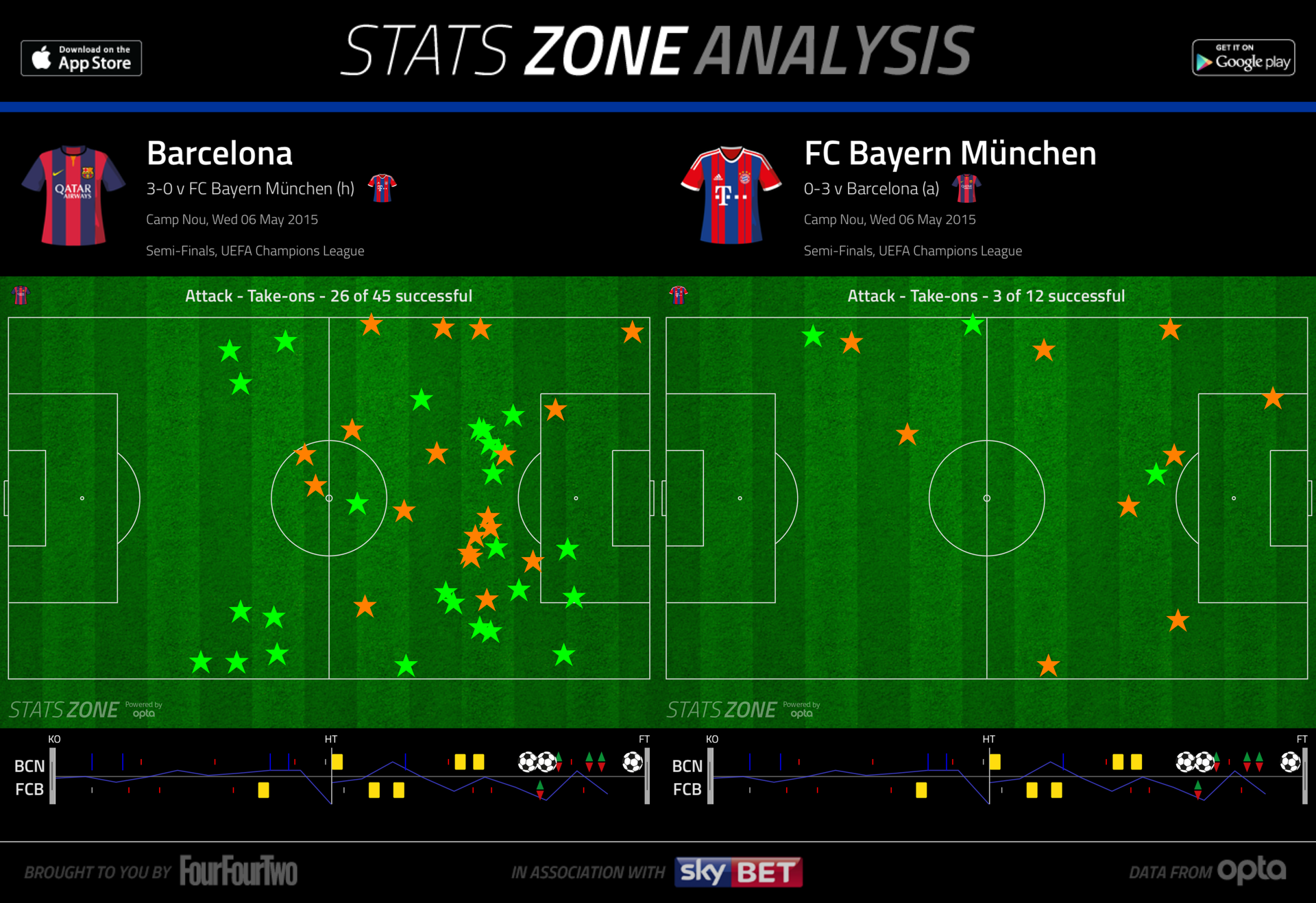

Looking back over the course of history, the development of football tactics isn’t really about formations or pressing, but about precisely what you do with the ball. In the early years, the major debate was about passing versus dribbling – and, in a very different way, that contrast was evident in Barcelona’s 3-0 victory over Bayern Munich last week. The passing game was, in itself, a huge innovation. Early football teams based their game around dribbling aggressively towards goal, with team-mates often ‘backing up’ to collect the ball if the player in possession was dispossessed, perhaps comparable to Rugby League. It was Queen’s Park, in the 1870s, who became the fathers of the modern ‘passing game’, which prioritised combination play over individualism. The modern Barcelona and Bayern Munich sides, of course, are primarily passers. They completed more than 1,000 between them in last week’s game, and one point of interest was the fact Bayern dominated possession, registering 55% – almost unheard of for an away side at the Camp Nou. But far more interesting were the dribbling statistics – and there, the difference was stark. Barcelona completed 26 of their 45 attempted dribbles, while Bayern’s figure was a somewhat pathetic 3 from 12. This, more than the passing, was arguably where the game was lost.

Dribble kings

There’s unquestionably been a shift at Barcelona over the last three seasons – since the Pep Guardiola reign ended, actually – to become more of a dribbling side. This is essentially because of the identity of Barca’s starting players. With the addition of Neymar, a tricky dribbler from the left, and Luis Suarez, a more physical, scrappy runner with the ball through the middle, they have changed their approach in the final third. It was once all about passing – Leo Messi would dribble, but others would make off-the-ball runs. Now, Barca’s attackers beat opponents solo. That was particularly obvious last week. Messi beat opponents 9 times – including the brilliant shuffle onto his right foot which pole-axed Jerome Boateng for Barcelona’s second goal – while Neymar beat 5 opponents in possession. Suarez and Iniesta were on 4 each.

For Bayern, amazingly, only one player showed an ability to dribble with the ball. Spanish left-back Juan Bernat completed 3 take-ons, but his attempts in this respect ended in disaster – when attempting to move forward down the left with the ball, he was tackled by Dani Alves, who squared for Messi to score.

The difference is illustrated neatly by the statistics, but it was obvious within the game too – Barcelona simply had another dimension to their attacking play.

Whereas Bayern’s pass-and-move football was often easy to read, and Barcelona’s defenders knew the way to defend against this approach, the Catalans' play had an element of surprise. Defending against Messi, for example, is so difficult because he’s an expert passer, dribbler and goalscorer. The same is true of Suarez and Neymar, and therefore Barcelona had the three most complete attackers on the pitch.

Men down

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

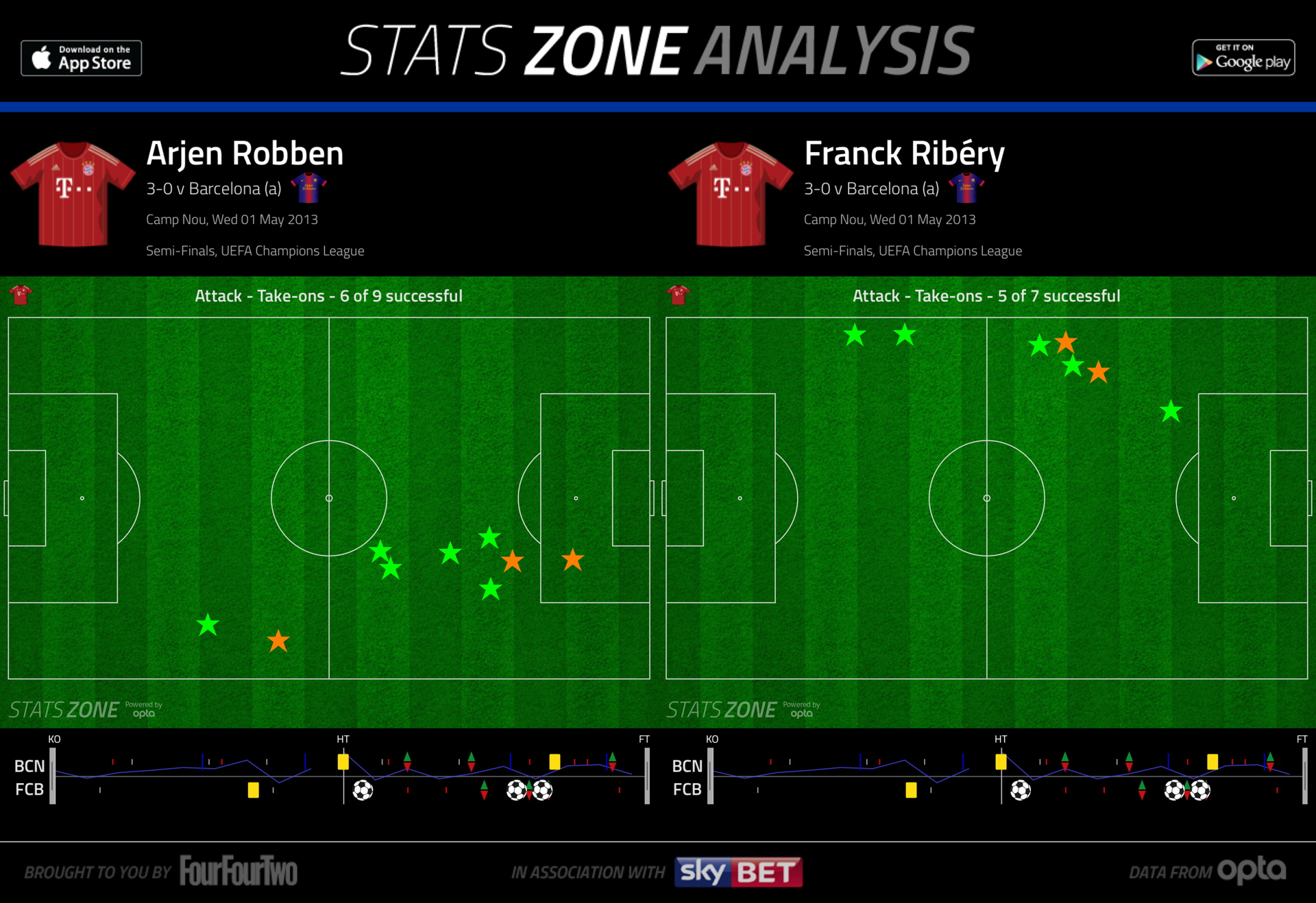

It’s something of a role-reversal from the meeting between these two sides a couple of years ago, when Bayern won 3-0 at the Camp Nou largely thanks to good counter-attacking football – and plenty of dribbling. The obvious difference is the absences of Franck Ribery and Arjen Robben this time around: two years ago, the positions of their dribbles summarised Bayern’s approach. They collected possession in their own half, roared past defenders and dribbled directly towards goal. This time, Bayern didn’t simply lack Ribery and Robben – they didn’t have any natural width or any attackers who can dribble.

Considering these two clubs pride themselves on possession play more than any others in Europe, it’s fascinating that dribbling has proved the difference. At the very top of European football it’s not enough to be good at one element of attacking – you need to be all-rounders.