The Best Footballers in the World… in 1966. Who comes top?

Had FourFourTwo been around (presumably under a different name) 50 years ago, who would have been in the FFT100? FFT’s launch editor Paul Simpson wonders...

Trying to decide the 100 best players of 1966 isn’t easy. There was no South American equivalent of the Ballon d’Or and many countries (Argentina, Brazil, Italy and Portugal, to name but four) didn’t select footballers of the year. That said, after poring over the events of an historic 12 months, certain players stand out.

In the lower reaches of this retrospective 100, you would find the usual blend of promising youngsters and fading veterans. The great Ferenc Puskas, who hung up his boots at the age of 39, might have featured on sentimental grounds. The magical, alcoholic Garrincha bowed out for Brazil against Hungary – his 60th cap and his first defeat with the Selecao. The only upside of that loss for Brazil was that a 19-year-old Cruzeiro midfielder namd Tostao, who would entrance millions in the ‘beautiful team’ of 1970, scored their consolation goal.

Another 19-year old to make his mark was lanky midfielder Johan Cruyff, whose 16 goals powered Ajax to the Dutch title. Cruyff was not an entirely unknown quantity – he was on the scoresheet as Ajax overwhelmed Bill Shankly’s Liverpool 5-1 in a foggy European Cup match in December – but, outside Germany, few had heard of 20-year-old Gerd Muller, a short, ungainly but nifty centre-forward whose goalscoring instincts seemed truly clairvoyant.

Muller was prolific enough, in his first Bundesliga season with Bayern Munich, to earn a call-up to the Mannschaft, although he didn’t make the final 22. Eight years later, his goal in Munich would crush Cruyff’s hopes of winning the World Cup.

There are countless players above the lower reaches but below the top ten, which means it's probably best to group them by trade: defenders (including goalkeepers), midfielders and forwards (wingers and strikers).

NEXT Which keepers and defenders get the nod?

The boys at the back

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Russia’s captain Valery Voronin was a stopper who, with the intelligence and technique to play on either flank, pointed towards a more creative future

Gordon Banks’s idol Lev Yashin could still turn it on in goal, as he showed with a stupendous save against Hungary in the World Cup quarter-finals. Ladislao Mazurkiewicz – Mazurka to teammates – was already showing the quality for Uruguay and Penarol, who won the Copa Libertadores and the Intercontinental Cup (against Real Madrid), that would prompt Yashin to anoint him as his successor.

The changing nature of the defender’s role was reflected in the World Cup. While England’s Jack Charlton and West Germany’s Willie Schulz epitomised the best of the old-school destroyer, Russia’s captain Valery Voronin was a stopper who, with the intelligence and technique to play on either flank, pointed towards a more creative future.

One pioneer of the new style was Velibor Vasovic who, as centre-back in the Partisan Belgrade that reached the 1966 European Cup final, impressed Ajax’s coach Rinus Michels with his willingness to turn defence into attack. Vasovic, who gave Partisan a shock lead against Real Madrid, would later help Michels perfect Total Football.

A decade after they had been pioneered by Hungary and Brazil, attacking full-backs were still in vogue. Giacinto Facchetti raided forwarded as an auxiliary attacker in Inter and Italy’s catenaccio system, and the ability of England’s full-backs George Cohen and Ray Wilson to make overlapping runs helped persuade Alf Ramsey that he could ease wingers out of his side.

The men in the middle

Pirri was the ideal central midfielder: energetic, brave, intelligent, good in the air and exceptional on the ball

In midfield, intensity was beginning to be as influential as natural talent, and 1966 produced its share of tireless heroes. The tragicomic vicissitudes of Alan Ball’s managerial career have obscured his qualities as a player; a master of the short game, always available to collect a pass out of defence and find a team-mate, Ball was good enough to break the British transfer record in 1966, when Everton paid £110,000 for him.

As good as Ball was, Real Madrid’s Pirri was arguably better. Though he – and Spain – disappointed at the World Cup, he was the coach on the pitch in the Real Madrid side that won its sixth European Cup in May. A former centre-forward, inside-forward and right-half, Pirri was the ideal central midfielder: energetic, brave, intelligent, good in the air and exceptional on the ball.

Yet 1966 was also blessed with its fair share of artists. Uruguay and Penarol playmaker Pedro Rocha was so gifted he could do whatever he wanted with the ball. And let’s not forget Antonio Rattin, captain of Argentina and Boca, whose red card against England – for nothing at all or consistent dissent, depending on your politics – has overshadowed the fact that he was described thusly by Bobby Moore: “Powerful, fine skill, good appreciation of what was going on around him. Knew the game inside out.”

In 1966, apart from a few Italian film directors like Pier Paolo Pasolini, there were no football hipsters as such. Yet in retrospect, the hipster’s idol would probably have been Andriy Biba, Soviet player of the year in 1966. Biba fulfilled the Bobby Charlton role as an advanced attacking midfielder in Victor Maslow's Dynamo Kyiv side, who may well have invented the 4-4-2 formation.

NEXT Which wingers get picked?

The wide boys

19-year-old George Best was dubbed ‘O Quinto Beatle’ by the Portuguese media after scoring twice in the European Cup against Benfica in March

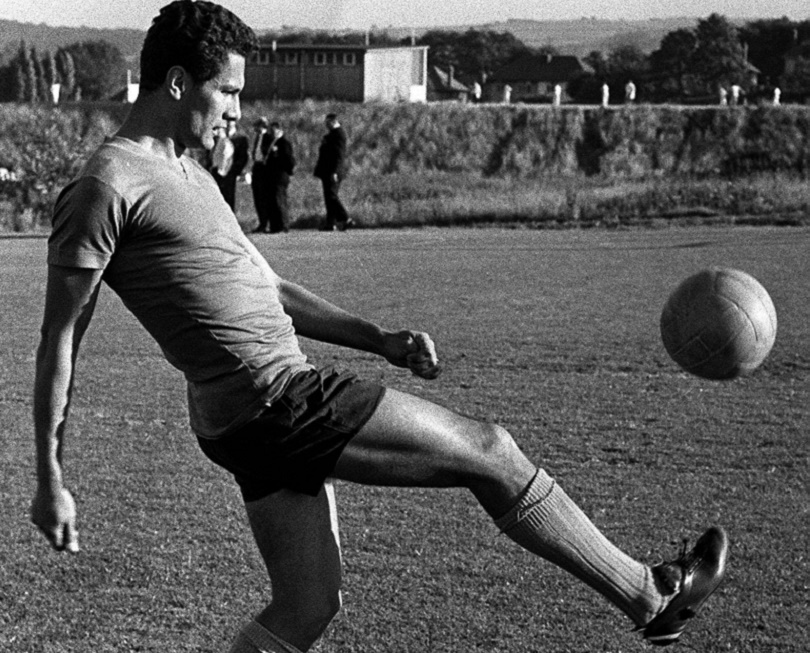

Although England’s World Cup winners were hailed as ‘Wingless Wonders’, 1966 was actually a kind of golden age for wizards on the wing.

Real Madrid’s European Cup winners had Paco Gento on the left (still effective as he turned 33) opposite Amancio, who was so tricky on the right he would, if playing today, inevitably be nicknamed Harry Potter. In Italy, Mario Corso, aka ‘God’s left foot’, defied critics who accused him of “hiding in the grass” and was instrumental as Helenio Herrera’s Inter won their third scudetto in four years.

And in Britain, wingers flourished. 19-year-old George Best was dubbed ‘O Quinto Beatle’ by the Portuguese media after scoring twice in the European Cup against Benfica in March. In Scotland, Jimmy Johnstone’s ability to jink through defences had won Celtic’s first Scottish title in 12 years. By the end of 1966, the future Lisbon Lions had cruised into the last eight of the European Cup.

The forwards

Jose Torres, who, despite playing alongside Eusebio for club and country, was one of the most effective centre-forwards in the game

Up front, even in an off-year when he was quite literally kicked out of the World Cup and Santos underperformed, Pele remained one of the world’s best forwards. Geoff Hurst came joint-14th in the Ballon d’Or voting, scant reward for becoming the first player to score a hat-trick in a World Cup final (a feat unmatched in the subsequent half-century). Even more remarkably, he wasn’t in the tournament’s all-star XI, losing out to West Germany’s Uwe Seeler, who had returned to form after tearing an Achilles tendon a year earlier.

On as many Ballon d’Or points as Hurst was Georgi Asparuhov, reductively tagged ‘The Bulgarian George Best’ because he was talented, good looking and drove an Alfa Romeo. A skilful inside-forward or centre-forward, Asparuhov scored Bulgaria’s only goal at the World Cup and, the year before, had inspired Levski Sofia to victory against Benfica.

Other strikers in contention would include: Jose Torres, who, despite playing alongside Eusebio for club and country, was one of the most effective centre-forwards in the game; Nantes’ hero Philippe Gondet, Europe’s most prolific league scorer in 1966 with 36 goals in 37 matches; and Belgian idol Paul van Himst – tracked by Barcelona and Real Madrid as the top scorer in an Anderlecht side in the midst of a record-breaking streak of five successive league titles.

All these players would have deserved their places in the upper reaches of FFT’s Best 100 Players of 1966. But who would make the Top 10?

NEXT The final selection

10. Silvio Marzolini (Boca Juniors and Argentina)

The only South American in the World Cup all-star team, Silvio Marzolini is arguably the best Argentinian left-back of all-time. At 26, he looked elegant even when he was tackling and loved to run with the ball – he rarely overran it either, instinctively sensing when the right pass was on. In 1966, he was slightly better than Inter and Italy legend Giacinto Facchetti and might be more highly rated if he hadn’t rejected lucrative offers to stay at his beloved Boca Juniors.

9. Helmut Haller (Bologna and West Germany)

Bologna’s Helmut Haller had moved to Serie A before the introduction of the Bundesliga and its consequent economic miracle for previously impoverished German players. He scored six during the World Cup, including the opening goal in the final. Effective, combative and histrionic when tackled, Haller inspired some to say that he’d learned to play football at Bologna and done the rest of his training at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts.

8. Ferenc Bene (Ujpesti Dozsa and Hungary)

Bene is now largely forgotten outside Hungary but he was a brilliant individualist, versatile enough to play anywhere up front. He scored four goals at the World Cup, and during Hungary’s 3-1 victory against Brazil (champions of 1958 and 1962) he and Florian Albert played some of the finest head tennis in the history of the game.

7. Gordon Banks (Leicester City and England)

As deserving of a place in the top 10 is Gordon Banks, whose nickname ‘Banks of England’ is a poignant reminder of an age when we implicitly trusted the banking system – and English goalkeepers. Banks’ impressive form at the 1966 World Cup is all the more remarkable considering the fact he'd missed the first nine games of the season after breaking his wrist while diving at a Northampton player’s feet during a friendly.

6. Mario Coluna (Benfica and Portugal)

Portugal captain Mario Colunagwas only 13th in the voting for the Ballon d’Or. Yet, blessed with enormous strategic intelligence, Coluna was as influential, at inside-left and left-half, for Portugal and Benfica as his fellow Mozambican, Eusebio.

5. Florian Albert (Ferencvaros and Hungary)

Hungarian centre-forward Florian Albert was blessed – or cursed – with exceptional game intelligence, as he never tired of telling his coaches. Deadly in the air and lethal on the ground, he won a standing ovation at Goodison Park for a dazzling performance in Hungary’s 3-1 win over Brazil. Selected as a striker in the World Cup all-star team, Albert was also joint-top scorer in the 1965/66 European Cup.

4. Bobby Moore (West Ham United and England)

England’s World Cup-winning captain has been so lionised it’s hard to see the player behind the legend. Yet as astute an observer as Matt Busby marvelled at his game intelligence: “He could see where the game was heading when the ball was 80 yards away – it cannot be explained unless clairvoyance has something to do with it.”

3. Franz Beckenbauer (Bayern Munich and West Germany)

Elegant, adroit and with a composure that belied his age – he was only 20 when he scored his first World Cup goal, against Switzerland – Franz Beckenbauer was voted the best young player of the tournament. Almost as inspired in attack as defence, he single-handedly changed the tactics of German football, establishing a longstanding national preference for a libero - although few were as imperious as the Kaiser.

NEXT Portugal's goal machine vs England's creator-in-chief

2. Eusebio (Benfica and Portugal), 1. Bobby Charlton (Manchester United and England)

Who was the world’s best footballer in 1966? The obvious candidates were great rivals and good friends, Bobby Charlton and Eusebio, famed almost as much for their integrity as their conspicuous genius. They shared, too, certain pathos. As a survivor of the Munich air disaster, it was easy to understand why Charlton might look haunted. The source of what Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano called Eusebio’s “sad eyes” remains more of a mystery.

As the creative linchpin of Sir Alf Ramsey’s World Cup winners, Charlton was probably the most influential player in that tournament, even though Eusebio, who scored nine goals as Portugal reached the semi-final, won the Golden Boot.

Neither player was perfect: at his best a player of fearful drive and marksmanship, Charlton sometimes struck passes which awed crowds but didn’t change the game. Eusebio ran in zigzags and scored goals from absurd angles but didn’t really like mixing it. During the 1966 semi-final against England, Portugal skipper Mario Coluna shook his fist angrily at his team-mate who hung back out of harm’s way.

Yet with Pele sidelined by injury, they were the best in the world in 1966: Charlton was voted European Footballer of the Year with 81 points, one ahead of Eusebio, the 1965 winner.

So if FourFourTwo had existed in 1966, its top 100 would almost certainly have started with Charlton, followed by Eusebio.

FourFourTwo's Best 100 Football players in the world 2016