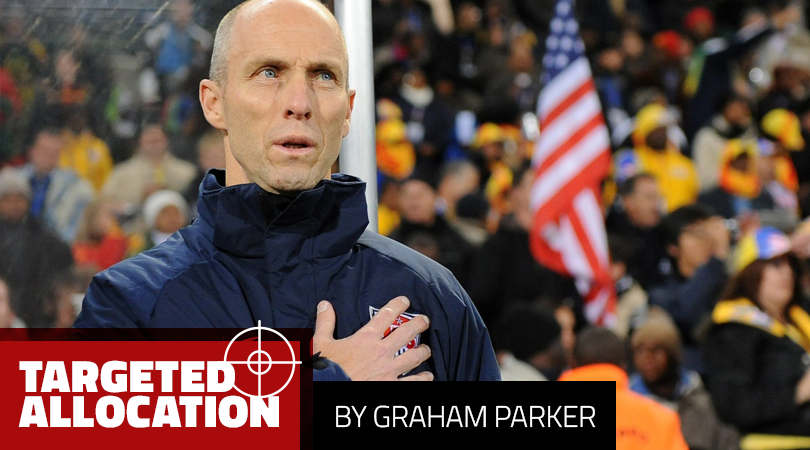

Bob Bradley's Swansea appointment also has U.S. football self-reflecting

Prejudices Bob Bradley will face in the Premier League are a good reminder for MLS and U.S. fans to assess their own biases, FourFourTwo USA columnist Graham Parker writes

Sometimes the football world gets perceptibly smaller.

On Monday, morning I was driving alongside the Delaware River, with New Jersey in sight through the fog. This being the era of digital globalisation, and wholesale imported content, I was listening to traffic reports from Manchester on satellite radio, followed by a live draw of the final qualifying round for the FA Cup, replete with Bishop Auckland, Chesham, Billericay Town and all the associations they evoked. I was enjoying the cognitive dissonance of the two superimposed parochial experiences when the news came through that Bob Bradley had been appointed Swansea City manager.

Yes, it’s a historic and symbolic moment for U.S. soccer and its fans — but what perhaps struck me first was how natural of a development it felt in that moment. As the programming shifted back to the U.S. and the understandable hype about the significance of this appointment kicked in, I was still thinking about the local news from Britain that I’d been listening to moments earlier, and thinking about how naturally this news fit there, right now.

Inevitable arrival

A U.S. coach in the Premier League was going to happen eventually, and of current credible candidates, Bradley has been on a shortlist of one for most of the past five years. That has been the case because, with characteristic lack of sentimentality or entitlement, Bradley has served his time in plain view. He has understood that in order to be considered for the type of job he has now landed, he must first make himself legible to those making the decisions. So he’s gone from challenge to challenge, and met each one, and in the process has translated an American soccer cradling into a European context where his skills can be read and understood within the sometimes-avowedly myopic world of English domestic football.

That’s not to say Bradley’s qualifications for the job will be instantly appreciated. New American owners installing an American coach has the potential to unsettle Swansea fans who’ve never heard of Bradley — though the New York Times reported on Monday that it was the club’s Welsh chairman Huw Jenkins who was most impressed by his meticulous preparations and knowledge when he interviewed him alongside Steve Kaplan and Jason Levien.

But Bradley is well prepared for that and will not be fazed. He has long known, if never quite accepted, that in the lopsided currency exchanges of the global game, a New Jersey football birthright doesn’t carry as much weight as, say, a Newcastle one. With that knowledge, he has scraped together his cultural capital the hard way. He may have been a top MLS coach and U.S. men’s national team manager, but it has been the period since he took the job with Egypt in 2011 which has set his course for Swansea. By conspicuously submitting himself to an extended apprenticeship that always held the danger of seeing him spiral off into obscurity, Bradley forced his way into consideration.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

It’s a small irony that as a coach, Bradley has taken the path vigorously touted by his successor in the national team job, Jurgen Klinsmann. Klinsmann has been damningly clear of the value of a European playing career for U.S. national team players, and he was visibly dismayed by the mass return of senior national team players to MLS in the lead-up to the 2014 World Cup – an influx that prominently included Bradley’s son, Michael, leaving Roma for Toronto.

No such return followed for Bradley — despite the fact that he’d be pushing at an open door at most MLS clubs. Not that he’s been shy about using the U.S. media to push his claim that he’s in the same category as some of the top managers in the game, but he's also been willing to prove himself well out of his – and to be frank, most top managers’ – comfort zone. Having missed out on the Swansea job, do not expect Ryan Giggs to be submitting an application for the now-vacant position at Le Havre...

Seb Stafford-Bloor: Bob Bradley and British football’s distasteful distrust of American managers

Self-reflection for all

As for the idea that Bradley's appointment now becomes a referendum on U.S. coaching: that would appear secondary to the appointment being made in the first place. Being the coach he is, Bradley is unlikely to fail so dramatically that the subsequent credibility loss goes continent-wide, but even if he were to fail, the fundamental shift in credibility happened when the owners took a risk on him. An American coach in the Premier League is not an unthinkable Ted Lasso joke any more.

That's important in the way both cultures, on either side of the Atlantic, think of the game. In England, and yes, Wales, American ownership of Premier League clubs has gone from satire-ripe novelty to just-part-of-the-landscape in the last couple of decades. Astute coaches and sporting directors have found value in American players, too, though not without a struggle for those players to overcome the suspicion that they peak too late, or lack inherent footballing intelligence (never a quality that's invoked innocently). And yet throughout that period, American coaches have generally been told… not yet. Until now.

The thing is, certain ingrained prejudices cut both ways. American soccer has slowly moved out of an unsplendid isolation over the last couple of decades, and given the structure of MLS in particular, there has been a certain reluctance to open the league up to the open market of the global game. The financial restrictions and structure of single ownership create a certain cultural exceptionalism that is not always for the good of the game.

Just last week, I was speaking to Orlando City manager Jason Kreis about the way that the idea of "shared ownership" of a project had begun to erode in U.S. football circles. I'd meant it largely as a painful but positive development, signalling MLS finding its level as it integrated more with a wider global football economy. I'd mentioned that, for example, there was a time when dissenting opinions could be quelled "for the good of growing the game" in this country, but that that's no longer such an easy appeal to make as it expands indisputably established and as the central culture of it becomes more fragmented.

Kreis thought that was fair comment, but was keen to assert that as someone who'd been with the league since the beginning, he didn't "want to lose that sense of ownership – that this is our project." It was an oddly emphatic statement, though not out of step with a tone I'd noted in previous conversations during his time with NYCFC – it's the fate of this generation of American coaches, and Bradley's before them, to not exist just as individual coaches with their own particular merits, but as avatars of American soccer, benchmarking themselves before someone does it for them and by default embracing a collective chip on the shoulder.

Natural scepticism

From that logic, it's understandable why coaches and players develop a certain defensiveness about the U.S. game, and their unique ability to understand it. It's not the cultural cringe that used to defer absolutely to European wisdom, but in itself it represents a certain reflexiveness that can be healthy or unhealthy depending on the individual (with Kreis it seems to provide a healthy proportion of his drive to prove others wrong). And to be honest, it is a reflexiveness that can at times be not a million miles away from the knee-jerk reaction to Bradley's appointment in some British football circles.

It's hard to avoid, too. When I think of my own reaction whenever a foreign coach is appointed in MLS, my first response is nearly always scepticism about how they'll navigate and understand the particular qualities of salary caps, roster building and travel within this idiosyncratic league. But whatever truths there might be in that, and however unprepared certain coaches have proved to be, it's not a universal principle that holds regardless of the talents, aptitude and temperament of the coach who comes in, and neither I, nor anyone else, ought to start from that position.

Bradley just transcended such a prejudice in getting to the starting line with Swansea. He'll be fine with that. In his own words, the man just wants "a chance". And God knows he's earned it.

And in doing so, he has narrowed a certain trans-Atlantic gap in thinking – yet another shrinking of distance in the ongoing globalisation of football. But just as it is a chance for Premier League culture to reflect on itself and its own prejudices and insecurities, it's perhaps a moment to turn inwards and reflect not on what it means over there, but what this moment means over here.