Bobby Robson at Barcelona: How one stormy season became the making of Pep Guardiola, Jose Mourinho and Ronaldo

In a Barcelona team that brought Bobby Robson, Jose Mourinho, Ronaldo and Pep Guardiola together, not even success was enough to avoid a bitter ending

This piece on Bobby Robson's stint at Barcelona was first published in the December 2021 issue of FourFourTwo – subscribe now!

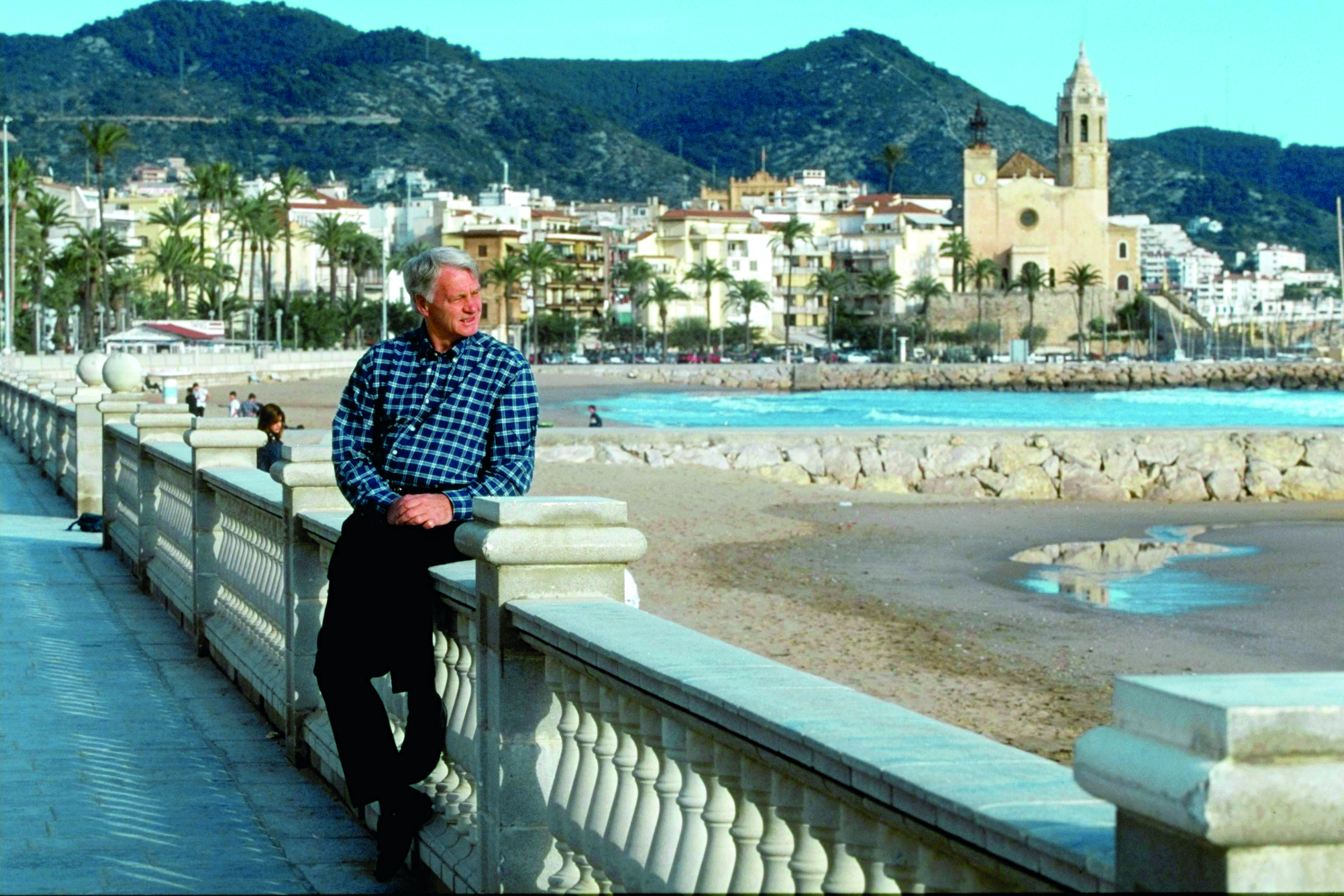

Everybody should see the sea, or a mountain, or walk in the woods each day of their lives,” Elsie Robson had told her husband, Bobby. And so each morning, the former England boss would drive along the promenade, looking over his right shoulder at the endless azure of the Mediterranean before hitting the motorway to training.

Twice before, Robson had declined this delightful way of life. He’d rebuffed Barcelona’s advances out of loyalty to Ipswich during their early-80s pomp, and later honoured his national service with the Three Lions, suggesting Terry Venables to Blaugrana chiefs instead. Aged 63, he didn’t say no a third time in the summer of 1996, although life in Catalonia wasn’t exactly his way of taking his foot off the accelerator and accepting a more relaxing job.

Johan Cruyff had just left the Camp Nou. Robson couldn’t speak a lick of Spanish, instead relying on his trusted translator at Sporting and Porto: the younger, dashing Jose Mourinho. The new Barça boss once described himself as a gunslinger arriving into the Wild West and having to convince a saloon full of towering figures to follow his lead. Robson was acutely aware of how intensely integrated the club was to Catalan culture, likening Barça games to battles; away grounds to foreign fortresses to storm.

It was also a fractured city, with the recently dethroned Dutch sheriff’s silhouette still looming large. This town wasn’t big enough for the both of them. Someone had to succeed Cruyff, though, who had been dismissed after a series of spats with president Josep Lluis Nunez.

“Robson came in at a difficult time,” says defender Abelardo, who had joined the club from Sporting Gijon two years earlier. “Cruyff had been such a massive part of Barcelona for getting on a decade – it was never going to be easy taking a job where the previous coach had established such a huge reputation.”

Nor was it straightforward to split Cruyff from the club he had come to define. The face of Total Football had become a mercurial architect in middle age, reshaping Barcelona in his image from foundations to skylights. He had delivered Los Cules’ first European Cup in 1992 and written the blueprint for how youngsters at La Masia would learn to play the game. He wasn’t sacked so much as overthrown.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

“Cruyff was the ghost in the machine – he haunted my early days,” Robson later confessed. Cruyff frequently watched matches from the stands, while his son Jordi was on the books when Robson arrived, only to join Manchester United for £1.4 million in the Englishman’s first summer.

Robson and Mourinho had marched into a club mired in political turmoil; one with egos and outrageous talent, but no major trophy to show for two seasons’ toil and backbiting. It was a team fully in transition: captain Jose Mari Bakero was featuring less and less, with a 25-year-old Pep Guardiola starting to wear the armband regularly. It was also a side that would perhaps never really feel like Bobby Robson’s, whatever he might achieve during his two-year contract.

The pressure was immense. At least those morning drives along the sea could help take the edge off.

"Ronaldo at Barcelona? He's not a man, he's a herd"

“Bobby,” notoriously frugal president Nunez snapped, “You know your job depends on this?” Robson’s seat in the dugout was still cold, yet Barcelona had just broken the world transfer record on a 19-year-old, simply on his recommendation.

“When Ronaldo came to Barça from PSV, there wasn’t the internet or social media, but there was a runrun – the buzz about him was gigantic,” recalls writer and LaLigaTV pundit, Graham Hunter. “There was a feeling of lots of elements all coming together in a cocktail, and there was a festival atmosphere about the Bobby Robson era.”

Laurent Blanc, Luis Enrique, Fernando Couto and a returning Hristo Stoichkov had signed that same summer, but there was no doubt who claimed top billing. It took the Brazilian just five minutes to announce himself as the new matador in town. With little more than a swivel and burst of pace, he danced past two defenders before unleashing a 25-yard opener in the first leg of the Spanish Super Cup against Atletico Madrid. By full-time he’d destroyed Los Colchoneros with another goal, following a glorious elastico assist for Ivan de la Pena in his side’s 5-2 win.

The carnival had arrived. A supercharged Ronaldo plundered 13 goals in just 11 league appearances as Barça reached the summit, two points ahead of Real Madrid. “I once saw Ronaldo score a goal for Barça where he beat five or six players,” Robson later reminisced of one such early match to FourFourTwo. “Diego Maradona at his best was the best I ever saw. Ronaldo would be a close second, though.”

That goal remains a vivid postcard moment two and a half decades on. The north-west city of Santiago de Compostela is the final destination of a 500-mile Catholic pilgrimage from southern France, and one night there

in October 1996, Ronaldo gained possession by the halfway line and mimicked the route. Zigzagging past a handful of defenders, he picked up speed, then spun out of their orbit. By the time the ball hit the net, Robson’s look was one of astonishment. The reaction is as iconic as the goal itself.

“Honestly, that goal was a disgrace,” says Abelardo. “You can see Robson putting his hands on his head in disbelief after Ronaldo scored, but we all did. I remember looking around and everyone was in the same pose. The best I’ve seen, totally unrepeatable by nearly any footballer alive. Maradona against England, Messi against Getafe and Ronaldo against Compostela. That’s it.”

Barcelona were beginning to click under Robson, with the festival feeling still flickering into autumn. Ronaldo followed his mesmeric Compostela strike with a sublime hat-trick at home to Valencia, battering through players like a wrecking ball through condemned buildings. Los Che boss Luis Aragones could only snarl on the touchline, perhaps aware that he would be replaced within weeks by Jorge Valdano, who famously declared of his predecessor’s tormentor, “Ronaldo’s not a man, he’s a herd.”

An 8-0 October annihilation of struggling Logrones was to define Robson’s tenure in many ways. The Camp Nou’s Cules olé’d their appreciation, but critics were less impressed with Bobby’s bulldozing Barça.

“The headline the next day in Diario Sport was ‘Muchos goles, pero muy poco futbol’,” says Hunter. “‘Lots of goals, but very little football’. There was a bit of snobbery from some sections, although it wasn’t a rebellion against him. There were plenty who adored Sir Bobby because they thought he was un caballero – a gentleman.”

Robson took the stick personally, however, calling it “cracking comedy”. He saw the split in the press as a reflection of a split fanbase, many of whom still mourned Cruyff’s more measured methods. Despite some factions not warming to their new coach, the team were still flying in La Liga by mid-November and into the Cup Winners’ Cup quarter-finals after despatching both Larnaca and Red Star Belgrade. Increasingly leading video sessions and compiling opposition scouting dossiers, Mourinho had become a media master.

“He didn’t manipulate the journalists, but he was very clever in making sure his profile was high,” explains Hunter. “He served Bobby well in that he had a knack of steering press conferences into safer waters.”

Barcelona managed to stay unbeaten long after Robson’s seaside excursions had turned chillier, until they surrendered their run at the hands of Athletic Bilbao in late November. Mourinho wasn’t quite so diplomatic on that occasion, contesting decisions and squaring up to Athletic’s lollipop-wielding coach Luis Fernandez. Mourinho’s swagger was simply staggering, and Fernandez – a Doberman of a boss – couldn’t believe the bottle. Guardiola had to drag the Portuguese away.

A 2-0 loss in December’s Clasico followed, before Barça squandered a two-goal lead at home to relegation fodder Hercules, losing 3-2. By now they were playing catch-up in the title race and jeers had replaced cheers at the Camp Nou. Meanwhile, Ronaldo – now the youngest ever recipient of the FIFA World Player of the Year prize – was embroiled in rows with club chiefs about when he could depart for international duty.

“It was a paradise of great football and great people,” says Hunter. “Yet for Bobby, plenty of s**tty things were also going on.”

Call it a comeback

Carrer d’Elisabeth Eidenbenz is a narrow road just behind the Camp Nou, with portly palm trees and overgrown grass. There’s a car park behind a mesh fence on one side, but it used to be the site of a training pitch.

This fence was a window into the world of Robson’s Barcelona, and the pavement used to be where fans, journalists or smitten girls, there to catch Ronaldo, would congregate. “My only manager was Cruyff until Bobby arrived,” right-back Albert Ferrer tells FFT, “but Bobby didn’t want to be the protagonist – he just wanted to be the coach of a team and create a good atmosphere.”

Robson and Mourinho’s dynamic was that of a headmaster and teacher overseeing the class. They worked perfectly together. Bobby’s first instructions to Jose at Sporting were, jokingly, that he was too handsome to stand near him. Even five years later in Catalonia, Robson maintained a professional distance from his players, while Mourinho was more matey with the group.

As a fellow native Portuguese speaker, Jose proved an ally for Ronaldo, and would often talk tactics and philosophies with Guardiola and Enrique. The former became Mourinho’s closest cohort; they hailed from markedly different backgrounds, yet their footballing philosophies were rooted in the practical ideals of building play from a solid foundation at the back.

“We saw and heard lots of things,” recalls Hunter about those days on the pavement. “Mourinho had come over from Portugal with Bobby and learned from him; Guardiola had a fantasy about what life at traditional old English football games would be like. I can’t tell you if they considered each other outright friends, but they were two very bright minds with a degree of international curiosity and experience. There was a click.”

Anglophile Guardiola was a favourite pupil of Robson’s, who appreciated his midfielder’s courage in speaking up at half-time. Pep in turn adored his manager, even writing to him years later asking to join Newcastle.

“The squad had many strong personalities,” continues Ferrer, now a LaLigaTV pundit. “Pep Guardiola, Hristo Stoichkov, Luis Figo, Ronaldo, Giovanni, Laurent Blanc, Luis Enrique, Juan Pizzi... but players with this personality helped us through any challenge.”

Robson’s biggest challenge at the Camp Nou came in March 1997 against Atletico in the Copa del Rey quarter-final second leg. Disapproval boomed in the giant bowl after a dreadful first half where Atleti had strolled into a 3-0 lead; Barça fans waved their white handkerchiefs en masse.

“I thought it was snowing in the stadium,” remembered Robson of that night. Atletico and Barcelona were frosty enemies as it was, but unbeknownst to the manager, Blaugrana directors had decided to sack him should the scoreline remain. Those inside the dressing room insist that Robson was unusually calm. What happened next took the Camp Nou’s collective breath away.

“Well, I guess Ronaldo happened,” laughs Abelardo, who played that night. “He scored twice and within little more than five minutes we were back to 3-2. [Milinko] Pantic quickly scored a fourth for Atletico, then Figo and Ronaldo brought us back level before Pizzi’s late winner. With players of that class you’re never out of a game. Beating a team as good as that Atletico 5-1 in just one half shows the level we were at that season.”

Barça’s comeback was as exhilarating as anything the venue had ever witnessed: pre, during or post Cruyff. Still, though, the press suggested that Robson’s players had staged a half-time rebellion in the dressing room. It took Guardiola, captain in the extraordinary remontada, to rubbish that theory the next day. “I thought, ‘I want to be a manager’ because of how he handled that situation,” he glowed years later.

Atleti and Barcelona faced each other six times that season, scoring 37 goals. On that March night, there was plenty of football too.

Backstabbed in the boardroom

Spectacular or sober: those were the two states of Robson’s Barcelona. In mid-April, another Ronaldo hat-trick obliterated Atleti’s barricades in a 5-2 win; a month later, Barça ground out a disciplined, mature 1-0 Clasico victory to close a yawning gap behind Real Madrid to five points.

Las Palmas were slain 7-0 on aggregate in the Copa last four, while Barça beat Gabriel Batistuta’s Fiorentina in the Cup Winners’ Cup semis. They may have been fighting a losing battle in the league, but were competing on three fronts with a stacked squad. “Bobby kept things simple,” says Ferrer. “He wanted to keep the momentum.”

Barcelona had two final dates circled in the calendar: the Cup Winners’ Cup against Paris Saint-Germain in May, and the Copa del Rey against Real Betis in June. Each night, Cules got to see the two faces of their team.

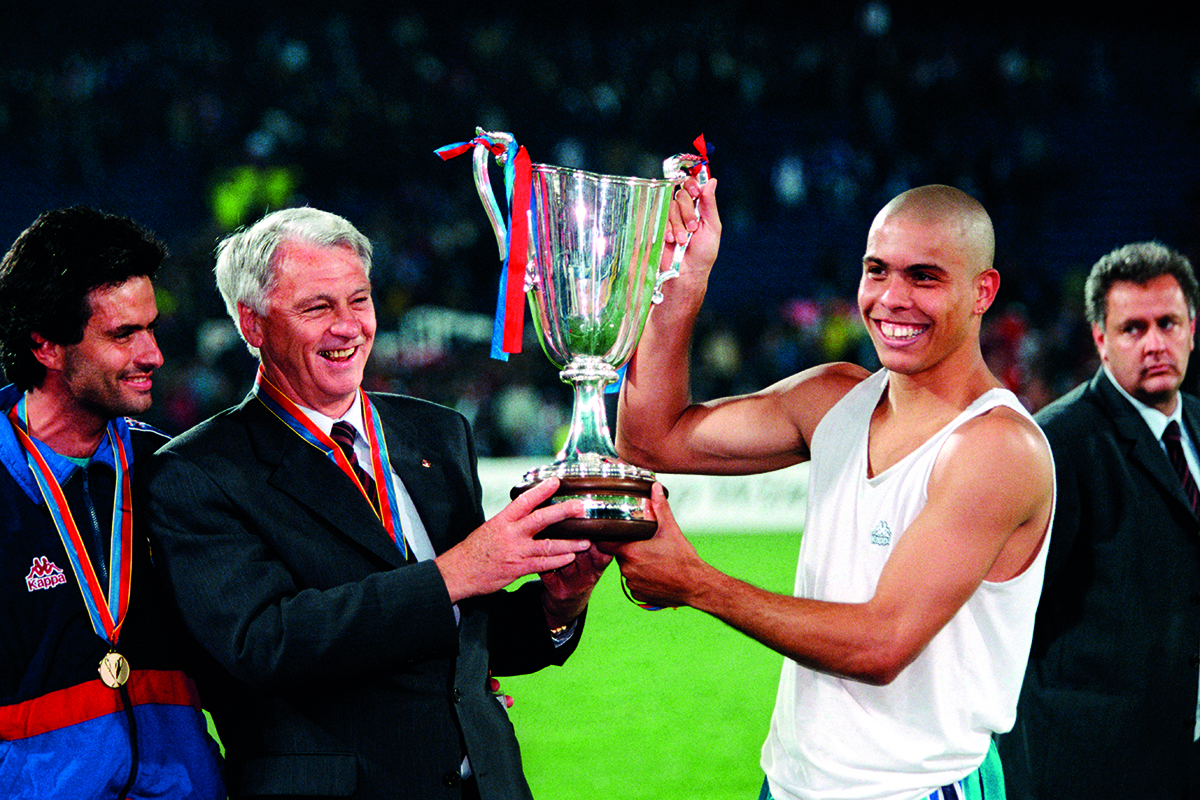

“Beating PSG was amazing,” says Abelardo of the first finale in Rotterdam. “They were the defending champions and had a great team, but I do think we were better on the night, even if it was only a Ronaldo penalty that sealed the trophy for us.”

Guardiola and Mourinho embraced at the final whistle, bouncing up and down on the spot. Ronaldo held one arm of the trophy, Robson the other, a big smile spread across the manager’s face. The celebrations were controlled, unlike the raucous Copa del Rey final at the Bernabeu in Madrid.

“I sat behind the goal with Barcelona fans and it was absolutely mental,” remembers Hunter. “It was 3-2 and went to extra time; it was a slugfest, it was fantastic, all the fans were going crazy. When Barça finally won, they played the club anthem in the Bernabeu over and over again.”

The two showpieces were six weeks apart. In between, worlds came crashing down.

Doomed Hercules needed little fight to beat a Ronaldo-less Barcelona 2-1 on June 1. The Brazilian’s last goal for the club came a week prior against Deportivo La Coruna, his 10th scoring league game in succession mere days before he was called up for Le Tournoi. As the title slipped from Barça’s grasp in his absence, O Fenomeno agreed to join Inter for another world-record fee. It was Figo, not Ronaldo, who inspired that Copa del Rey triumph, R9 having left a week earlier.

“That was a huge surprise for everyone,” says Abelardo. “We all thought Ronaldo could define an era at Barcelona, similar to what Leo Messi would do a decade later. We were shocked that the directors would let a player like that leave, one who would guarantee 30 goals a season.”

Robson wasn’t amused either, but worse was to follow. Amid whispers about his own future, he asked Mourinho to eavesdrop into conversations that the directors were having. His worst suspicions were confirmed before the Copa del Rey final. Louis van Gaal was to replace him; an overlooked clause in Robson’s contract gave Barça the right to move him upstairs to an ambassadorial role.

This caballero was seldom as distressed. He was the calmest man on that fretful night against Atletico, took the slugfest Betis final in his stride and didn’t get overly involved in Ronaldo’s intra-club conflicts. A few months previously, he’d turned down an offer from his beloved Newcastle to stay in Catalonia (“no one sacks Barça,” Nunez had retorted). Now, Robson was white-hot with fury. “I’ll tell you what you can do,” he told a sheepish Joan Gaspart, Barça’s vice-president tasked with breaking the Van Gaal news. “Get rid of him. I want the job.”

Robson hadn’t exactly failed. Barcelona missed out on the title to Real by two points, though the Copa del Rey celebrations at the Bernabeu – which doubled up as Robson’s leaving bash – perhaps softened the blow. The Cup Winners’ Cup victory had restored their European reputation and, after putting his neck on the line for Ronaldo, the striker had delivered 47 goals in 49 games. What more could Bobby do? Despite everything, he still felt like he’d embarrassed his bosses.

It ain't what you do…

In 1989, Johan Cruyff and Louis van Gaal fell out over a misunderstanding at a Christmas dinner. The Ajax legends never reconciled. Cruyff viewed himself as an expressionist; he saw nothing of himself in Van Gaal’s football, despite their shared roots and similar values.

It must have grated to see Van Gaal in his dugout far more than it ever had watching Robson. However, perhaps the latter’s tenure reaffirmed something to all three of them: it’s not just what you win at Barcelona – it’s how you do it.

More than a decade later, in 2008, Robson’s protégé would learn this. The outstanding candidate for the Camp Nou throne following stellar spells at Porto and Chelsea, European heavyweight Mourinho was overlooked in favour of Barça B boss, and old pal, Guardiola. Mourinho, like Robson before, was furious – he felt belittled.

Barcelona knew Mourinho was more than capable of delivering trophies, while both he and Guardiola shared a raging intensity for rigour and detail. But it still wasn’t enough, and nor would it ever be: Guardiola was given the nod because he was a certified Cruyffista. Where once the pair were comrades on that training pitch tucked behind the Camp Nou, they would soon be very public adversaries.

Robson had no such time for bad blood after his own betrayal, wishing Van Gaal the best and accepting Nunez’s offer to become director of signings. He encouraged Jose to stay and learn from his successor.

“The decision to move Robson on felt very strange,” Abelardo tells FFT. “We still noticed him around the club, but there wasn’t the same day-to-day contact with him any more. I don’t know whether he enjoyed it or not, but he still seemed his usual happy self.”

Robson travelled the world in his new role. By day, he’d sit near the pool of whichever five-star hotel Barcelona had sent him to; by night, he’d scout. He had time to read, time for golf. It was a much-needed sabbatical.

“He was so wounded that I don’t think he was urgently keen to get back into coaching,” admits Hunter. “He definitely pushed the idea with anybody he talked to that his gentle revenge on the club was to keep taking their money for a wonderful job that allowed him to sit by the beach. There was a point where he said to me, ‘You know what? This is the greatest job in the world’.”

For a while, Robson took Elsie’s advice, saw more of the sea and took more walks in the woods. He would soon get back in a dugout, though; shortly before, Hunter had bumped into him at a Fulham restaurant.

“I’d written a column about why it was the right time for Bobby to go into management again,” says Hunter. “He soon responded by ringing me at home. I said, ‘You’ve lived the good life for long enough – you’re a people person. It’s about what gives you satisfaction and what you like doing.’”

Robson took the advice, first for a second spell at PSV, before making it to Newcastle after all in 1999. Management wasn’t just what he liked doing: he was exquisitely good at it. So good, in fact, that he said yes to one of the most difficult jobs in Europe – following the idolised Cruyff – and did so well that he forced his bosses to uneasily promote him.

That season’s Camp Nou cocktail remains one of Barça’s most memorable campaigns. Bobby had delivered two major trophies, won the fans’ respect and signed a phenomenon to remember for years to come.

Robson never did work alongside Ronaldo, Guardiola nor Mourinho again. O Fenomeno would fulfil his immense promise as a World Cup winner, always speaking fondly of his former boss. Guardiola received a letter back from Robson wishing him good luck ahead of the 2009 Champions League Final against Manchester United, meanwhile. Two months later, the old master passed away aged 76 after a long battle with lung cancer.

“If he’s half as good a manager as he was a player for me, he’ll do OK,” Robson once remarked of his midfield general.

Mourinho also ensured he kept in contact with his mentor, after the 1996-97 season prepared him for the future turmoil in which he would revel. It was those experiences at Barça which taught ‘the Special One’ how to survive on a touchline in the heat of Clasicos and cup clashes; how to handle the preying media; and what a dressing room crammed with world-class players looked like up close.

Perhaps Mourinho learned some deeper truths from that year in Catalonia, too. Make time for yourself, enjoy nature, always be the calmest man in the room and try to remain a gentleman when you can. And remember: success doesn’t necessarily deliver what you deserve. Even if, like Sir Bobby Robson, you take on the impossible job and win.

LaLigaTV is the only place to watch all of the action from the 2021-22 La Liga campaign

For a limited time, you can get five copies of FourFourTwo for just £5! The offer ends on May 2, 2022.

Mark White has been at on FourFourTwo since joining in January 2020, first as a staff writer before becoming content editor in 2023. An encyclopedia of football shirts and boots knowledge – both past and present – Mark has also represented FFT at both FA Cup and League Cup finals (though didn't receive a winners' medal on either occasion) and has written pieces for the mag ranging on subjects from Bobby Robson's season at Barcelona to Robinho's career. He has written cover features for the mag on Mikel Arteta and Martin Odegaard, and is assisted by his cat, Rosie, who has interned for the brand since lockdown.