Bonkers by the Bosphorus: Why Fenerbahce vs Galatasaray is more than a game

The Istanbul derby: so violent the authorities tried to ban it, so bitter the whole world is watching, so important the fans of two teams will do anything. Steve Bryant and Dan Brennan reported for the February 2006 FourFourTwo magazine

“You are all sons of whores,” come the chants of Galatasaray fans, as they tear up their seats and hurl chunks of red and yellow plastic onto the pitch of their team’s crumbling Ali Sami Yen Stadium.

By Istanbul derby standards, the 351st clash between ‘Cim Bom’ and their arch rivals Fenerbahce has been a fairly quiet affair. The target of the home fans’ vitriol is not, though, their friends from across the Bosphorus, who have just sneaked a 1-0 win, but their own club’s management and directors.

It is probably just as well that Galatasaray’s prim and polite chairman Ozhan Canaydin has boycotted the match in protest at Fenerbahce fans being allowed to attend.

In all some 1,000 away supporters, crammed into one small corner of the stadium, have managed to make it into the ground, and their mood is, by contrast, ecstatic.

Victory has set a Fenerbahce club record of 12 league wins on the trot and carried the champions six points clear at the top and well on track for a historic third straight title. To add considerable insult to Galatasaray’s latest injury, the small blue and yellow wedge of Fener fans, though outnumbered 30 to one, have severely embarrassed the massed red and yellow ranks of the Cim Bom.

“Ali Sami Yen’s gone silent, they’re all listening to us,” sang the jubilant away contingent in the second half, and they had a point. During the first half, the drums, whistles and songs of the Galatasaray fans drowned out whatever noise the small cluster of ‘Yellow Canaries’ dared to make.

But by the 80th minute, after yet another failed attempt by faded national icon, Hakan Sukur – these days known even to Galatasaray fans as Donkey Hakan – the home support is utterly subdued.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

“We won the football match, but we also won the fans’ ‘game’ decisively,” beams Cuneyt Aytac of Fener supporters group Antu after the match. “We are very happy with this result.”

Global dimension

Indisputably the biggest event in the Turkish football calendar, the showdown between the Yellow Canaries and Cim Bom is a game with a global dimension, too.

Supporters munching on their doners and meatballs outside the Ali Sami Yen have travelled from across Turkey; some have even ventured from across Europe, with fans from Germany and Holland swelling the numbers. And with a sizeable football-mad Turkish diaspora scattered across the planet, the games also draw a crowd in smoke-filled cafés from Hackney to Moscow.

Forget Glasgow. Forget Barcelona. This is the biggest derby in the world. I’ve been coming since I was 12. I don’t smoke or drink, I just save all my money for this

“Forget Glasgow. Forget Barcelona. This is the biggest derby in the world,” boasts Galatasaray supporter Gökhan ahead of the latest set-to. The 20-year-old has made the 870-mile journey from Gaziantep near the Syrian border – a 26-hour schlep on the train.

“I’ve been coming since I was 12. I don’t smoke or drink, I just save all my money for this,” he adds, munching on pine nuts, the nibble of choice for the Turkish football fan.

Two hours later, it seems an awful long way to come for what has been, by common local consensus, one of the flattest derby encounters in years. His team look a pale shadow of the flagship Turkish side that used to humble European giants on a routine basis and that defeated Arsenal to win the UEFA Cup in 2000.

But even in defeat, Gokhan can draw comfort from slagging the opposition. “Fenerbahce are the worst team in the world,” he mutters. “The foulest, the lowest, the most dishonourable. They’re nothing and their fans are even less. We don’t hate them because they’re big and rich, it’s more than that. Galatasaray are an ethical team, honourable. But Fenerbahce are all about money and buying success.”

A Cim Bom banner inside the ground reinforces the view that these days Galatasaray find themselves clutching at reasons to be cheerful: “Success comes and goes,” it tells the players, “but your nobility is enough for us.”

Subverting the paradigm

Istanbul derbies don’t fit neatly into any of the classic paradigms for local rivalries. There is no ethnic split between the clubs and no religious divide, although historically, at least, social class played a part in forging the identity of each.

In the 1970s, Kurthan Fisek, a leading Turkish academic (and Fenerbahce fan) summarised the differences between Istanbul’s three leading clubs thus: Galatasaray, he said, were the club of the Europeanised aristocracy, Fenerbahce the club of the bourgeoisie, while the city’s third club, Besiktas, were supposed to be the team of the working classes.

Fisek’s definition holds some water but, according to local sportswriter and radio broadcaster, Bagis Erten, the modern reality is more fluid. There are unsurprisingly, plenty of posh Besiktas fans and no small number of poor Galatasaray supporters.

Other major derbies have ethnic or religious differences or class at their roots; here, each of the three big clubs has to compete for every new-born child

“Other major derbies may have ethnic or religious differences or class at their roots, but in Turkey, things are different,” says Erten. “Here, choice of club is like a kind of democratic citizenship. Anyone can become a supporter of any club. Each of the three big clubs has to compete for every new-born child.”

Besiktas, Istanbul’s oldest club, having been founded in 1903, represent a third way of sorts. They don’t inspire the same intense hatred among either of their neighbours, and any success is tolerated by both.

The perception of Besiktas as the team of the working classes is bolstered by the fact that in recent decades the club has drawn much of its core support from the traders, porters and labourers who work in the maze of shopping lanes around the old fish market in the Besiktas district, on the European side of the Bosphorus. They have also tended to attract the sympathies of Istanbul’s beleaguered minority groups, the Greeks, the Armenians and the Jews.

Galatasaray’s roots, meanwhile, lie at the opposite end of the social spectrum. The club was founded by old boys from Istanbul’s equivalent of Eton.

The Galatasaray High School in the heart of the European part of Istanbul is a 400-year-old institution built to provide a French-language education for the elites of the Ottoman Empire, and it was there, in 1907, that Ali Sami Yen convinced a group of his friends that they should start a football team, presenting them with a ball repaired with leather cut from his own shoes.

“Our aim,” he wrote, “was to play in an organised way like the English do, to have a set of colours and a name and to beat non-Turkish teams.” Two years later, in the first ever Istanbul derby, they defeated Fenerbahce 2-0 with one of the goals scored by an English ex-pat by the name of Horace Armitage.

NEXT: Switching allegiance

Switching allegiance

Armitage was the first of 54 players to play for both clubs. Changes of allegiance being relatively commonplace, they don’t tend to generate too much heat. The recent case of Israel international midfielder Haim Revivo is a notable exception.

A Fener fans’ favourite, Revivo walked out on them suddenly in January 2003, claiming ill-treatment and, not short of offers from around Europe, appeared to cock a snook at his old employers by signing a two-year deal across the Straits.

He probably thought better of his decision when, during a stint laid-up in hospital, he looked out of his window to see the building besieged by angry Fenerbahce fans brandishing banners bearing the legend ‘Traitor’. A few months later he was heading back to Israel.

Today, all three big Istanbul clubs are a fusion of a wide variety of commercial and sporting interests. The leading Turkish clubs are rarely, in fact, just football clubs, but go under the broader sobriquet of sports clubs.

Besiktas is nominally a gymnastics club. Galatasaray has its own basketball team, an athletics squad, a rowing team, and even a team of equestrians. And it has even gone back to its educational roots by establishing its very own eponymous university.

Expanding fanbase

With commercial growth, the fanbase of all the clubs has expanded, and now embraces supporters from across Turkey, with all of the country’s ethnic minorities well represented. The Kurdish rebel leader Abdullah Ocalan – as far from the image of a French-speaking aristo as you could hope to find – may have spent the 1980s and 1990s waging a violent separatist campaign against the Turkish state, but he still found time to follow the fortunes of his favourite team.

Galatasaray comes from a private school but most fans are not. And that creates problems. The management has always distanced itself from the fans. They treat us like stepchildren

Clues to Galatasaray’s Frenchified past are still occasionally evident, though. On the night FourFourTwo visits the Ali Sami Yen, a banner pays homage to the ‘Le Lion de Bosphore’.

And though the bilingual, privately educated elites that once formed Galatasaray’s fanbase are now a small minority, they still dominate the boardroom, something which continues to irk the club’s rank and file support.

“Galatasaray comes from a private school but most fans are not,” says Mehmet Aktop of ultrAslan (ultraLion), the club’s biggest supporters group. “And that creates problems. The management has always distanced itself from the fans. They treat us like stepchildren.”

Exemplifying Asian Turkey

Fenerbahce, on the other hand, have, under current chairman Aziz Yildirim, managed to put decades of internal fighting behind them. More than any other Turkish club they have cracked the merchandising game, selling branded paraphernalia by the bagful at their Fenerium stores.

Yildirim has also invested in the ground, making Sukru Saracoglu Stadium, on the Asian side of the Bosphorus, by far the best purpose-built football venue in Turkey.

In this sense, Fenerbahce – a club built on the new money of an economically thriving Anatolia – is a microcosm for the rapidly modernising Asian Turkey: ambitious, hardworking, financially astute.

The club’s identity with the Asian hinterland goes all the way back to Fenerbahce’s most famous fan: Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the hard-drinking general and statesman who is regarded as the founder of the modern Turkey in 1923, and who is supposed to have blessed Fenerbahce with a wish for their “eternal success”.

Laying claim to the support of such a talismanic national icon is controversial, but most now accept that Ataturk did have a special affection for Fenerbahce, and the story of the great man’s visit to the ground by the shores of the Marmara Sea in 1918 is enshrined in the club’s official history.

This is the reason the older generations love Fenerbahce: the club played an important role in Turkey's war of independence, and we're very proud of that

The club and its fans are fiercely proud of their support for the war Ataturk fought against invading Greeks to establish the Republic of Turkey on the wreckage of the Ottoman Empire. Club folklore tells of midnight intrigue when Fenerbahce took advantage of its waterfront location to help smuggle arms and support from then-occupied Istanbul to Ataturk’s army in central Turkey.

"This is the reason the older generations love Fenerbahce," explains Antu’s Aytac. "The club played an important role in Turkey's war of independence,” he says, “and we are very proud of that.”

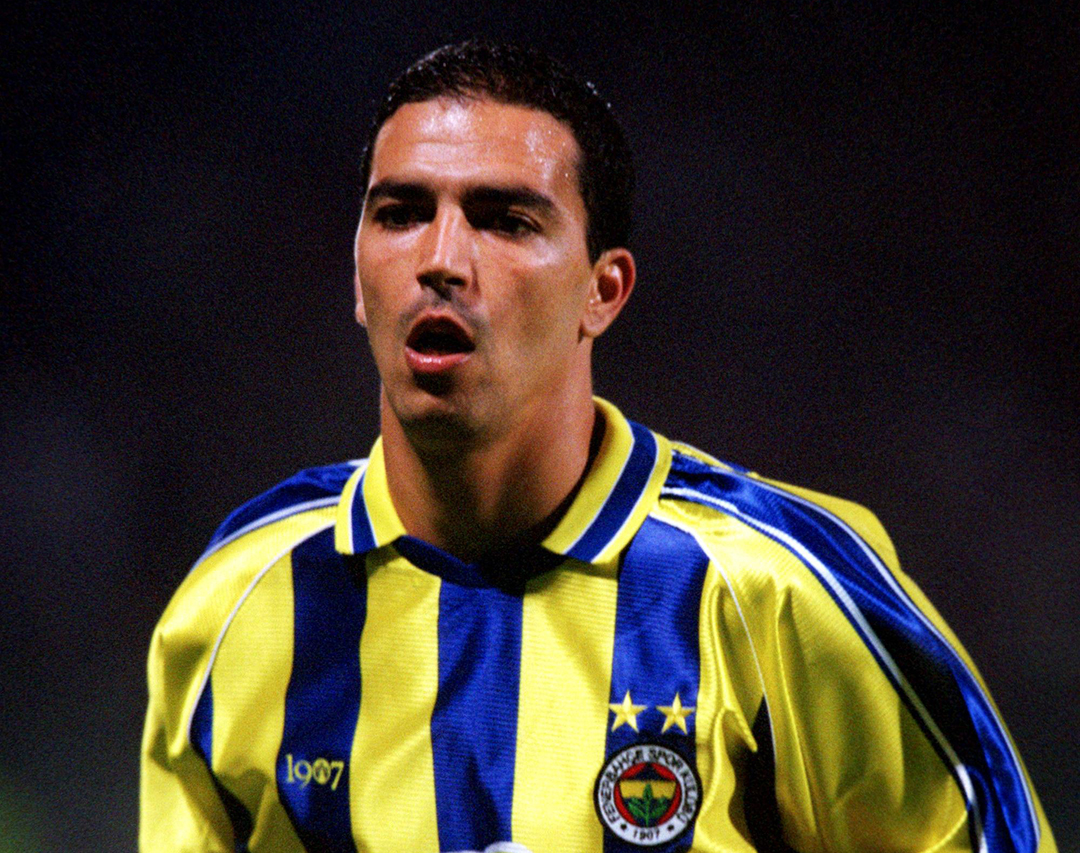

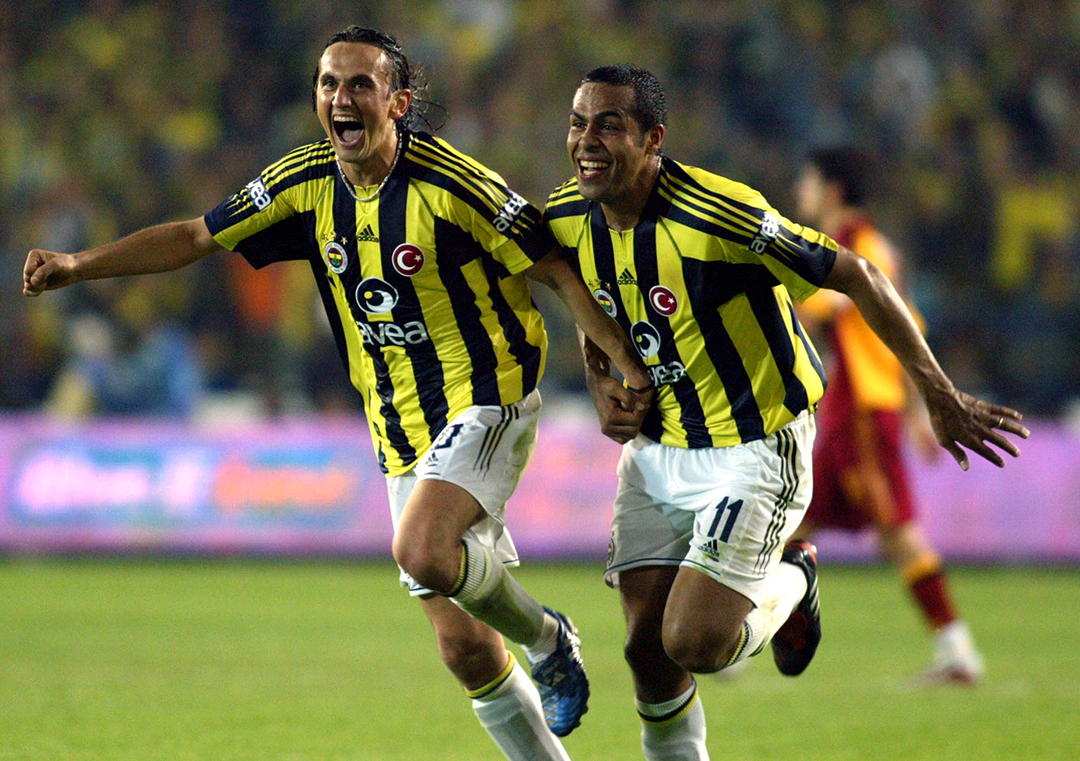

Though falling some way short of matching Ataturk's iconic status, the players from both clubs are fully aware that the Istanbul derby is their main opportunity to earn their stripes, a chance to write themselves into the history books. Take the example of Tuncay Sanli, whose goal opened the floodgates in Fenerbahce’s now legendary 6-0 win over Galatasaray in November 2002, says it was the game that set him up for the rest of his career.

“That was my most important match ever. It was my first Galatasaray match and I scored. There have been other important derbies for me but doing well in the first one is very, very special as a Fenerbahce player,” he tells FourFourTwo.

That pasting added further heat to what was already a particularly spiky encounter. There had been more trouble than usual before the game, the kick-off being delayed by thick clouds of smoke from scores of flares, and visiting fans had to be frogmarched out of Sukru Saracoglu by the police for their own safety.

Away restrictions

These days restrictions on away supporters mean that sort of situation is avoided, but Sanli mourns the old days when the grounds were split 50-50 between the two sides. “Nobody wants trouble, but in the past the atmosphere was better and of course we need our fans, we want to hear them.”

The 6-0 win probably ranks at the top of Fenerbahce’s many recent derby victories. Close behind is another 1-0 smash and grab at the Ali Sami Yen, back in 2000. Galatasaray, then boasting Gheorghe Hagi in his pomp, were reigning supreme at home and in Europe, beating all-comers on their way to their UEFA Cup triumph. Predicting a basketball score for the match, the Galatasaray officials had enraged rival fans by requesting an enlarged scoreboard for Fener’s visit.

But it didn’t go to script. The only goal was scored by the visitors’ Ghanaian Samuel Johnson, and the victory inspired a Fenerbahce corruption of a Galatasaray song that Yellow Canaries fans love to this day:

“Galatasaray say they’re conquerors of Europe,

They say all their fans are gay,

They say they are a star in peoples’ hearts and moon upon their souls,

But we f**ked their mothers nicely, Galatasaray.”

Nothing is so guaranteed to enrage a Turk as an insult directed at his mother. But the Galatasaray fans return the insult with interest, with a reference to one of Fenerbahce’s frequent European debacles.

“You went to Europe,

And disgraced us,

The gay canary,

How Barcelona f**ked your mother!”

NEXT: Short of the Euro elite

Short of the Euro elite

Given Fenerbahce’s Champions League mauling at home to AC Milan several days before they face Galatasaray in the first derby of the 2005/06 season, the jibe can be easily tweaked to suit the circumstances and remains a particularly effective response. Local kingpins they may be right now, but their aspirations to join the European elite look as unattainable as ever – a fact that their own head coach Christoph Daum admitted recently.

Let’s be realistic: before we run around saying how great we are, we need to develop young players more effectively – and we need to stop throwing things at buses and players

“There’s a big difference between the Champions League and the Turkish Supercell League,” said the German. “Let’s be realistic about Turkish football’s place in the international scheme of things. Before we run around saying how great we are we need to develop young players more effectively and we need to stop throwing things at buses and players.”

All in all, the last couple of years have been a rapid comedown for Turkish football, following the delirium of Galatasaray’s UEFA triumph in 2000, and a third-place finish for the national team in the last World Cup. The fact that their clubs have reverted to whipping boys in Europe has been compounded by the national team’s failure to make it to Euro 2004 or Germany 2006.

That stark reality makes the battle for local bragging rights all the more important. Fenerbahce head the overall tally with 130 wins to 113. And these days, Galatasaray have to delve some way back in time for derby victories to cherish.

One that stands out is their Turkish Cup victory in 1996, the infamous match in which head coach Graeme Souness earned a place in the derby pantheon with an act of adrenaline-fuelled bravado by planting a massive Galatasaray flag in the centre of the turf at Fener’s Sukru Saracoglu Stadium. It ensured him hero status with the Cim Bom faithful; but he almost sparked a riot in the process.

The next thing I remember is Graeme rushing past me with the flag. I hear they’re still selling T-shirts with that picture on it

Dean Saunders, who spent a season with Galatasaray in the mid-’90s and whose goal it was that gave Galatasaray a 1-0 first-leg lead recalls the encounters vividly. “I’d scored from the spot in the first game; I’d probably have been hung if I’d missed. And then we went to Fenerbahce for the second leg. It was hostile, very hostile, but great fun to play in.”

With the aggregate scores tied after normal time, Saunders was on target once more in the 115th minute, clinching a 2-1 aggregate win for the visitors. “The next thing I remember is Graeme rushing past me with the flag,” Saunders tells FFT. “I hear they’re still selling T-shirts with that picture on it.”

The win was a triumph for the small group of Galatasaray fans who’d braved the trip over the water. “All night we’d felt under pressure. We were outnumbered and it felt like we were Millwall fans away at Chelsea,” remembers Aktop. “Then we won and Souness came up to us and took one of our flags and planted it. It was the most natural and spontaneous thing.”

The jackasses back down

Such scenes are a far cry from the prevailing mood of the Galatasaray faithful for much of tonight’s derby.

Before the start of the current season, representatives of Istanbul’s three big clubs met with the police and the city governor to discuss how to handle their matches. Their decision to ban away supporters from all of the city’s derbies caused fury among fans, who blame hysterical media and club managers for exaggerating the level of violence at Turkish grounds.

In the aftermath of the violent scenes at the Turkey-Switzerland World Cup play-off last November, the authorities have been more determined than ever to use the Istanbul derbies to show the world, and FIFA in particular, that Turkey is capable of organising high-profile matches without trouble on or off the pitch.

Yet, predictably enough, the ban proved completely impossible to enforce. Earlier this season, ahead of their derby away to Besiktas, some 200 Fenerbahce fans disguised themselves in the black and white of the opposition to enter the stadium, before stripping off en masse to reveal their true colours. Surrounded by thousands of Besiktas fans, it was a risky move, but one that saw them score a major tribal triumph.

“The moment we started chanting, the two sides just separated naturally. The Besiktas fans gave us space. But then the police came in and kicked us out,” laughs Antu’s Aytac. “I don’t understand why the police were so surprised.

"We’d already written and faxed them saying that we didn’t accept this ban and that we were going to the match anyway. We even gave them our names and phone numbers. We’re not going to stop supporting our team just because some jackass says we can’t go.”

In the end, the “jackasses” backed down in time for tonight’s game, yet the arrival of the Fenerbahce team at Ali Sami Yen offers as clear an illustration as you could wish to see of the gulf between fan culture and the sterile FIFA fairplay paradigm that the Turkish authorities are keen to embrace.

Flowers, cologne and chocolates

Outside the ground, a phalanx of police, in full body armour, muscle onlookers – FourFourTwo included – out of the way to form a corridor that will allow the Fener bus into the ground. Galatasaray fans who can get close enough, hurl plastic cups and obscenities at the curtained windows.

Once inside, however, the Fenerbahce team are greeted with a bouquet of flowers. As they step off their coach, Galatasaray club officials hand out chocolates and splash lemon-scented cologne on the visiting players. It is the kind of slick piece of PR posturing that infuriates and alienates many Galatasaray fans.

“Cologne and chocolate?” says an exasperated Aktop, shaking his head in disbelief. “Sure, you shake their hands. You welcome them. That’s normal. But cologne and chocolate? It’s just embarrassing.”

Under the watchful gaze of the police, the Fenerbahce fans assemble near the ground, before squeezing through a single narrow stairway into their allotted space in the south stand where their presence is, in a manner of speaking, welcomed by the home fans. The fact is that no true football supporter wants the Istanbul derby to be stripped of its fan rivalry.

Look at Italy. Look at Greece. Can you tell me a derby anywhere where things haven’t been thrown? This is our reason for existence – it shouldn’t threaten people

“Look at Italy. Look at Greece. Can you tell me a derby anywhere where things haven’t been thrown? The idea that you can ban away fans is an idiocy. How can that be possible?” asks UltrAslan’s Aytop. “This is our reason for existence – it shouldn’t threaten people.”

“They even want to stop us swearing,” fumes Antu’s Aytac. “It’s unbelievable. That’s part of the culture!”

Dean Saunders agrees that the passion of the Turkish support is something to be celebrated not sanitised. “Football means an awful lot out there. Players like Tugay (Kerimoglu) and Emre Belozoglu are more famous than the president. And sometimes the fans may go a bit berserk but that’s better than having no passion at all like some countries,” he says.

Tonight, fans and players alike seem to lack passion. The game’s only goal arrives seconds before the half-time whistle. Brazilian Marcio Nobre leaps to get his boot onto a high ball and send it past Galatasaray’s onrushing keeper Faryd Mondragon.

It’s the one moment of drama in an otherwise uninspiring game, dominated by Fenerbahce’s midfield enforcers Marco Aurelio and Stephen Appiah. Their pixie-like winger Tuncay Sanli shows the odd flash of inspiration down the flank, but for the most part there is little to coax a lonely Nicolas Anelka out of his default sulk mode.

The Galatasaray fans’ protest after the final whistle notwithstanding, the match passes without any of the predicted trouble. “Our fans were a little subdued,” admits Aktop. “Partly because after the Switzerland game there was a wave of stress and, in my opinion, excessive self-criticism.”

But then contrary to the image sold by the local and international media, most Turkish supporters will tell you that football violence has been on the decline over the last decade.

There used to be fights with stones and bats. Then in the early 1990s knives started being used and people started being killed rather than beaten up. I remember a guy killed in Macka, and another in Taksim

“There used to be all kind fights with stones and bats,” remembers Antu’s Aytac. “Then in the early-1990s these fist and stone fights became more dangerous and knives started being used and people started being killed rather than beaten up. I remember a guy killed in Macka, and another in Taksim.”

By the mid-1990s the three groups had agreed a “terrace peace” that laid down the basic ‘rules’ for ambushes and outlawing of knives. “Though there were isolated incidences of beatings here and there, after that there were no more clashes of large fan groups,” continues Aytac. “Things are much more ‘in order’ compared to 1980s and 1990s.”

Galatasaray fan Mehmet Aktop agrees that fans now police themselves more effectively than the authorities and he blames the media, who continue to represent Turkish fans as unemployed louts, and the “industrialisation” of Turkish football for blowing up fears of violence out of proportion.

If the establishment’s recent efforts to sanitise derby matches have done one thing, it is to strike a rare note of harmony among both sets of rival supporters. “One reason tonight’s derby was not one of the best,” muses Aktop, “was because they are doing their best to kill off all the pleasure and the tension that surrounds the game”.

His voice tails off as he shakes his head in dismay, but the glint in Aktop’s eye suggests neither Galatasaray nor Fenerbahce will back down without a fight. The next time the two sides meet, at the Sukru Saracoglu on April 23, expect normal service to be resumed.

This feature first appeared in the February 2006 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe!

Gregg Davies is the Chief Sub Editor of FourFourTwo magazine, joining the team in January 2008 and spending seven years working on the website. He supports non-league behemoths Hereford and commentates on Bulls matches for Radio Hereford FC. His passions include chocolate hobnobs and attempting to shoehorn Ronnie Radford into any office conversation.