Borussia Dortmund: Inside Europe's most happening club

FFT discovers the secret formula of Germany's most enviable outfit and their mercurial coach...

"What, in heaven’s name, are Monsters of Mentality?” Borussia Dortmund coach Jurgen Klopp treats FourFourTwo to one of his trademarks – a brief but bellowing burst of laughter – as we ask him the question.

Then he strokes his 10-day beard (another trademark) and takes his time to answer the question, knowing he is talking to a foreign magazine whose readership might not be that familiar with his team’s recent history.

We are sitting in the plush lobby of a hotel in La Manga, southern Spain, where the club are conducting their winter training camp to prepare for the second half of the Bundesliga season. And, of course, the knockout rounds of the Champions League – a competition for which many now consider the German champions dark horses. Well, maybe even horses of a lighter hue.

“I think it was after the Mainz game that I coined this term,” Klopp finally says. He is referring to an intensely fought Bundesliga match, played three days after Dortmund had run riot in the Champions League once more, beating Ajax 4-1 in Amsterdam. Away at Klopp’s former club, Mainz, Dortmund fell behind early but came back to win thanks to a brace from striker Robert Lewandowski, Poland’s incumbent Footballer of the Year.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

“What I wanted to express in that moment was that my boys just don’t give in,” Klopp says. “This has been another season in which they had to face new challenges. Often – not always, but often – they have dealt with them remarkably. If you then find yourself in a Bundesliga game that doesn’t go your way, only a few days after a fantastic Champions League outing, yet prove that you are willing to go beyond your limits... well, this constitutes outstanding mentality for me. The boys buckled down and turned the game around.”

SEE ALSO Editor David Hall went to Spain and fell in love with Dortmund

He pauses for a moment but never glances sideways, like so many people will do during a conversation. Throughout conversation his eyes rest on you, not in an unfriendly manner, but firmly. The same intensity and focus that he brings to a game or a training session is also on display here – and will be again later, during an unusual photo shoot.

“Actually,” he continues, “this is what thrills me about football and what fascinates me the most about my team. Because having talent is one thing, but much more important is what you do with it. And in this regard we have been well on track for a couple of years now, I think.”

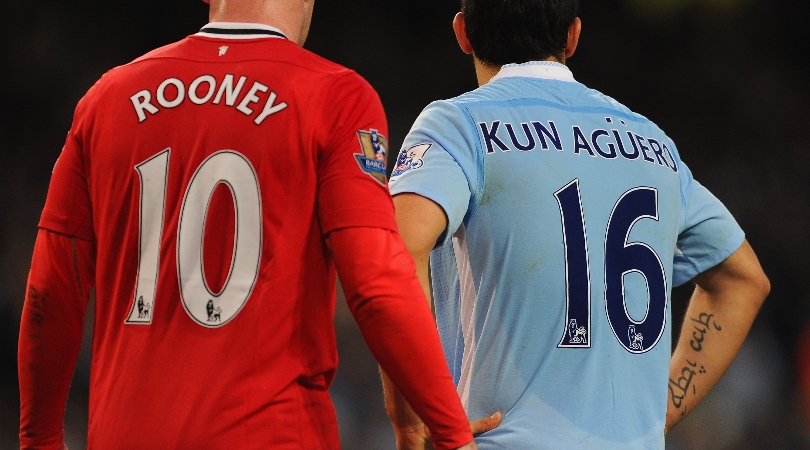

His team’s rise has indeed been steady rather than sudden, although most people outside Germany didn’t really sit up and take notice until Dortmund’s masterful display at the Etihad in early October. While there’s no denying that the team’s performance was nothing short of spectacular that day (“It was one of the best games I’ve ever seen, and I’ve seen a few – we were almost terrified out there at how perfectly our plan came together,” says Klopp), it wasn’t the first time that a bunch of youthful unknowns from Dortmund had totally outplayed a star-studded City side.

In August 2010, the two clubs contested a pre-season friendly in Dortmund. The Citizens had just spent £74m on new players in the preceding month alone, but the most conspicuous men on the pitch were wearing yellow rather than sky blue: a then-obscure nimble Japanese midfielder by the name of Shinji Kagawa – signed for only €350,000 – and an 18-year-old with silky skills called Mario Gotze, who’d been playing for Dortmund since he was nine.

As Klopp’s team took City apart, easily winning 3-1, the club’s supporters in the stands slowly began to suspect that something really big could be shaping up here. Yes, it was only a friendly. But the team had such fluidity of movement and an almost palpable sense of enthusiasm that there was a definite buzz in the stands.

Clearly, an already good side had taken the next step and was on the verge of being very good. In a way, this game was the starting point of a string of performances so amazing that some Dortmund fans reputedly still wake up at night with the sudden fear that it’s all been just a dream.

An adult season ticket is as cheap as £160

But it wasn’t the beginning. As happens so often (especially at this club, as we’ll come to see), the beginning was a moment of crisis. “It was about three-and-a-half years ago that we chose the path we are now pursuing,” says Klopp. “We had a string of bad results – six Bundesliga games without a win – even though we didn’t play badly. With 10 games left before the winter break, we held a training camp and told the boys they would get an extra three days off over the festive season if they – as a team – covered more than 118 kilometres in each of those 10 games.”

This distance equals 73.3 miles. In most of the following 10 games, the players would exceed this mark by a considerable margin, but they didn’t manage to reach it in every game. Yet the coach granted them their extra holidays regardless. “I did that because the extra effort the team put in immediately translated into more liveliness on the pitch,” Klopp explains.

“We were more assertive, we created superiority in numbers – all the things you associate with additional effort.”

Effort is, indeed, a key word here. Dortmund have been in the international headlines quite a lot this season, and not because they dominated a Champions League group containing the reigning English, Spanish and Dutch champions.

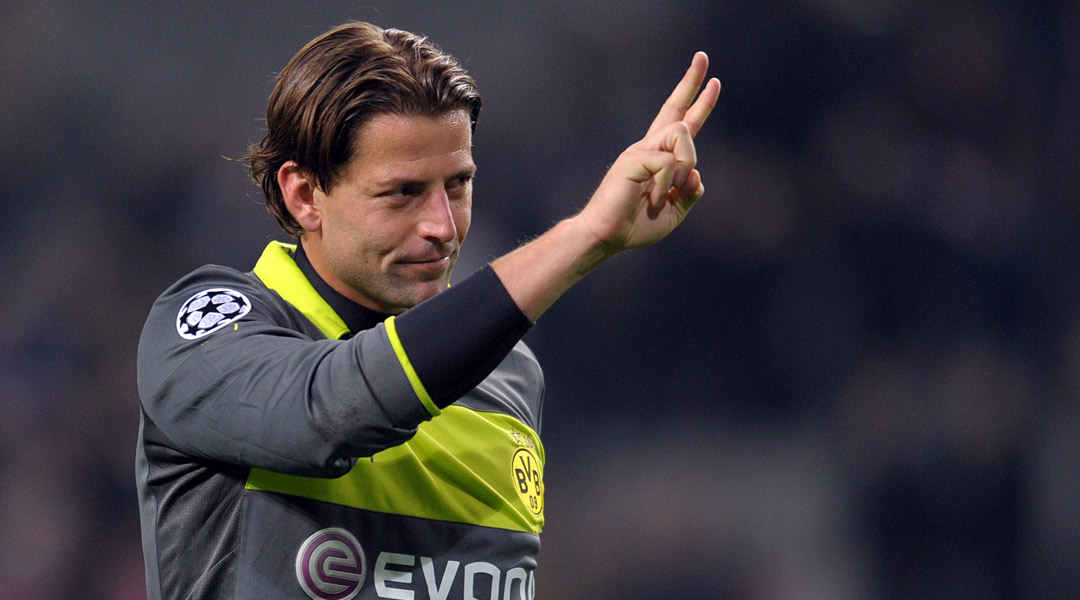

There’s also the side’s youth: the average age of the XI that started the game at the Etihad was barely 24, a figure distorted by the presence of veteran goalkeeper Roman Weidenfeller, the only team member older than 27.

Then there’s the fact that so many players are homegrown – nine men who saw action in Manchester hold German passports. And we mustn’t ignore one mind-boggling detail, especially when you look at the company Dortmund kept in that group: only one player in the entire squad has cost the club more than £4m (more about him in a minute).

Finally, Dortmund have become a bit of a pet subject for those English fans and writers who bemoan the state of the modern game, because Dortmund’s large support is not only faithful and passionate but has the enviable luxury of following this exciting team at a more than reasonable price (the cheapest adult season ticket sells for £160) while watching domestic home games from what is said to be the largest terrace in the world.

But the one thing that has left the most lasting impression on the rest of Europe this season is something else – the team’s football, an often thrilling style based on constant movement that is breathtaking in every sense of the word.

Yes, there are regular flashes of individual brilliance: Gotze’s flicks and tricks, say, or the way Marco Reus, Germany’s Footballer of the Year, controls the ball while running at full speed, or all those moments when Mats Hummels – a centre-back, for chrissakes! – moves upfield and sprays nonchalant passes with the outside of his foot like a reborn Franz Beckenbauer.

But above all, what stands out is the total team effort. “The pressing game is important for us,” explains Robert Lewandowski. “It is our strength and we work on it all the time. We train it constantly.”

A few hours before FFT sits down with the striker who is currently targeted by so many clubs, Borussia held an arduous, demanding training session under the Spanish sun to hone the team’s pressing. Or rather, what they call Gegenpressing in Germany – counter-pressing.

The idea is that if an attack is thwarted, if you lose possession anywhere near the other team’s penalty area, you don’t retreat and regroup but do the exact opposite – you move further upfield to win the ball back immediately.

It’s what Spain and Barcelona do so well and what many teams have tried to copy. Dortmund are one of the few to have done it successfully, perhaps because Klopp’s ‘Monsters of Mentality’ understand that putting in that extra effort pays off; they have realised that running, running, running will be rewarded. And so everybody runs, even strikers like Lewandowski, a player who would in the past have been labelled a targetman.

“In modern football, everybody has to run and play pressing, whether he’s a defender or a striker,” says the Pole. “It’s not a problem for me as a striker because I know that pressing gives us a chance to score goals, as we’ll often win the ball high up the pitch, close to the other team’s penalty area, in the danger zone.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by another of the team’s dangermen, 23-year-old Reus. “The offensive players benefit from the fact our counter-pressing is so good, because we get to the other team’s goal much quicker,” he tells us. “But in a way that’s just a bonus. The idea of counter-pressing, Klopp points out, is that it’s “the shortest route to defence”.

Like everything else he does, he uses this strange turn of phrase with deliberation. Because while his players do run a lot, they rarely have to cover large distances at a stretch. A short sprint is all it takes for an attacker to put pressure on a defender who’s just won the ball. But isn’t this approach very risky, when there’s all this space behind you when you push that far upfield?

“No, not at all,” Klopp interjects before the sentence is even finished. “It’s not risky because it all happens so far away from your goal. The only problem with counter-pressing is that you cannot train it as a tactical measure. You can’t tell the players: ‘you stand here and if this happens, you run there’. Instead, you have to train the impulse. It has to be an impulse to move into a ball-winning position immediately after losing the ball. You don’t teach a situation; you teach the impulse until it becomes a natural action.”

The finer points of these drills are actually the responsibility of Klopp’s long-time Bosnian assistant, Zeljko Buvac, while the boss keeps a watchful eye and shouts instructions and encouragements.

Mourinho approached Klopp and asked: “Where’s your tracksuit?”

Communicating with people, and not just players, is obviously one of Klopp’s most impressive skills. The noted German monthly Stern ran a piece about him last year that was headed ‘The Art of Motivation’, and it’s an open secret that his presence at this club is a major reason why players want to come to Dortmund.

Last winter, Bayern Munich – Germany’s most famous, most successful and most moneyed club – openly courted Reus, who was then under contract at Borussia Mönchengladbach. A high-ranking club official went as far as to say: “If Bayern really want to get a player, the club will sign him. We have enough power of persuasion in every regard to bring him to Munich.” Seventeen days later, Reus announced he would join Dortmund in the summer. One reason for his decision is that he was born in Dortmund and sometimes watched the team from the stands as a kid.

But it goes without saying that professional footballers don’t choose their employers simply on account of sudden pangs of nostalgia. “Klopp and I had a talk,” Reus tells FFT. “He has a way of convincing you quickly. He has a vision a footballer understands; a vision I like and which suits me. I was looking forward to training under him.”

Reus says this not long after a gruelling training session during which he didn’t just have to chase balls and put defenders under pressure all the time, but was also asked to play in defence himself at one point, as part of a back four made up entirely of offensive players. But like everybody else on this team, he seems to actually enjoy putting in all that extra effort. “Playing for Borussia is a lot of fun,” Reus says. “It’s a loose, casual club.”

This is evident not only on the pitch but off it. During our chat, Klopp is clad in comfortable sportswear. Not because he’s just come back from the training ground or to please the club’s supplier – it’s just the way he usually looks. Unlike quite a few modern coaches, he doesn’t follow the games from the sidelines dressed in the latest Italian threads, exuding calm assurance. Instead he jumps, darts, gestures, points, waves and hollers, applauds and complains, celebrates and mourns with total abandon while donning a hooded sweater and a Borussia baseball cap.

The reason you may not be familiar with this image is that – out of respect for the competition’s unspoken dress code – Klopp has decided to tone down his act and wear more stylish clothing during games in the Champions League. (Which is why Jose Mourinho approached Klopp ahead of Dortmund’s home game against Real Madrid in October with a mischievous grin. The Madrid coach extended his hand and greeted him with the words: “Where’s your tracksuit?”)

Saying that Klopp has moulded the team in his image would be stating the bleeding obvious. But he seems to have done more: namely, inspire the whole club.

During our entire three-day stay at the posh golf hotel in La Manga, we only saw one single member of Dortmund’s large contingent who was dressed in anything but informal sports clothes; even the press officers and the stadium announcer wore tracksuit bottoms and T-shirts while capping their evening in the hotel bar.

The single exception was the supporter liaison officer, who was there to assist the two dozen fans who had followed the team all the way to the southern tip of the continent. He wore blue jeans. You get the impression that Dortmund follow the example set by the coach and are deliberately cultivating their image as a down-to-earth, relaxed, welcoming club.

Our in-depth look at the club’s inner workings did not begin in La Manga but a few weeks earlier, in snow-covered Dortmund.

Even here, at the club’s headquarters, the same easy-going approach was in evidence. Nobody in the spacious building was in any way formally dressed and when we sat down with Dortmund’s leading executives for a chat about the past, present and future, CEO Hans-Joachim Watzke and director of football Michael Zorc needled Carsten Cramer, the marketing director, because he was wearing a suit jacket.

If the press officer hadn’t repeatedly reminded us that FFT had been granted “unprecedented access”, it would have felt like visiting a groovy late ’90s internet start-up rather than stepping into the inner sanctum of Europe’s most happening football club.

But it used to be different. Very different. At the turn of the century, Dortmund all too often exuded the sort of blasé standoffishness you associate with Wall Street brats who think they’ve made it because they are juggling somebody else’s millions.

At the time, Dortmund had just become the first (and so far only) club in Germany to float shares on the stock market. The club were also branching out into other businesses, even starting their own sporting apparel company from scratch, and trying to have success on the pitch the way everybody else did it – by signing star players for huge transfer sums and paying them absurd wages.

It all went horribly wrong, and since this disaster was ultimately the real beginning of the current renaissance – more than either of the Manchester City games mentioned, more than Klopp’s decision to ask for more effort after six winless games in 2009, even more than Klopp joining Dortmund the year before that – it’s imperative to have a look at what happened back then and why.

“If you tell a German fan he is just a customer, he is going to kill you”

After many years during which the league was regarded as dour and unglamorous, it has now become trendy among hip football people to see the German Bundesliga as something of a promised land: a competitive and fan-friendly league largely free of the excesses – financial and otherwise – commonplace elsewhere.

A lot of this is actually true, but what often gets overlooked is that the German club structure is totally different from the English model, making comparisons difficult, even impossible. In fact, when the Dortmund people we met during our extensive stay at the club use this very word – verein, which translates as “club” – they are essentially talking about something entirely different from what an Englishman understands by that term.

English football clubs have been businesses almost since the game’s dawn. In Germany, they were actually prohibited from being businesses until the turn of the millennium and even now they aren’t really proper companies. Traditionally, German clubs have been public, non-profit, multi-sports associations operating for the common good of the community they represent and run by their members.

It was only in the late ’90s, when that system seemed antiquated among the hustle and bustle of the football boom, that clubs were allowed to turn their professional football divisions into limited companies, with proper CEOs instead of the old-fashioned presidents and so on, in order to become more professional and attract investors.

However, a rule was put in place that said 50 per cent of the shares of such a limited company, plus one share, had to remain in the possession of the parent club. This is the now-famous ‘50+1’ rule. At the time, it was considered counter-productive in some quarters, because how can you attract an investor if you deny him the chance to actually take control of the enterprise he sinks money into?

But now, after a decade of Russian oligarchs, Arab sheiks, American entrepreneurs and Malaysian businessmen buying up the English game, this strange rule suddenly looks quite attractive, as it basically means that German clubs cannot be bought or sold and cannot be owned by an individual or a company.

“In the long run, it’s the better solution,” Hans-Joachim Watzke, Borussia’s CEO, replies when we ask him why he and most of his Bundesliga colleagues are such fervent advocates of the 50+1 rule even though it discourages private investment.

“Whenever you have investors, some kind of corporate demeanour begins to engulf the club. And that’s not our mentality. The German fan wants to have the feeling that he is a part of the whole. In England, the fan is now basically a customer and can, by and large, live with that.

"But if you tell a German supporter that he is just a customer, he’s going to kill you. He has to feel connected to the club and that’s only possible through the 50+1 rule, because when you really get down to it, the parent club’s members are still in control. Of course we run the limited company autonomously, but if the members one day think I should leave, they can sack me.”

“Also, what’s wrong with wanting to be master in your own house?” Dortmund’s director of football Michael Zorc chimes in. “I wouldn’t want to be dependent on the whims of a powerful investor. And the fact that some English clubs are still in a better financial situation than we are has nothing to do with Mr Glazer or some Sheikh spending money; it’s because they earn much more from television deals and international marketing.”

The 50-year-old Zorc was born and raised in Dortmund and played in more league matches for the club than any other player. In 1997, he was part of the team that upset Juventus in the Champions League final to bring club football’s biggest trophy to Dortmund. It was the proudest moment in the club’s history, but in a way it was also the moment when things began to go wrong.

Having made it to the top, the club desperately tried to stay there by signing big names for huge sums (the nadir being Marcio Amoroso for £22m).

When clubs were allowed to turn their football divisions into businesses, Dortmund jumped at the chance and not only set up a limited company but also went public in October 2000. It earned the club a ton of money, but that was soon spent on transfer fees and wages, whereupon Dortmund suddenly found themselves in football’s dreaded vicious circle: you need an expensive squad to be competitive and regularly succeed in Europe, because only that guarantees enough income to sustain the squad.

It was around this time that Watzke got involved with Dortmund, initially in the parent club. “In a prospectus which was published for the shareholders in 2000 or 2001,” he says, “I saw that Borussia Dortmund were ‘seeking to develop other business activities in order to become independent from sporting success’. It was the greatest rubbish I’ve read in my entire life. If you stink on the pitch, it’ll never work. Which is why our credo now is: it’s only about football.”

When the team at last began to stink, Dortmund’s high-flying hopes crashed to earth. Suddenly there was no more money coming in to pay off the debts and in early 2005 the club came within a whisker of having to declare bankruptcy, which under the German system would have meant automatic demotion to amateur football. The club’s fate was very literally in the hands of a ragtag group of small-time investors who – through an investment fund – had lent the club money and were now told they might have to wait longer than planned to rake in a profit. Had these men and women put their collective foot down and said they wanted money right here, right now, Borussia Dortmund would have gone belly up with immediate effect.

The psychological effects of that tension-filled day, on both the club’s fans and officials, cannot be underestimated. It not only taught a large contingent of the team’s support that there are things more important than silverware, it has also governed the club’s politics ever since. “There’s a headline above everything that we do,” says Watzke. “That headline is: we want to have maximum sporting success, but we will never again go into debt for it.”

Watzke, who is 53 years old, comes from the Sauerland, a rural, hilly region of Germany whose inhabitants are said to be conservative and down to earth, gruff but honest. Many people who know him well say that he fits that cliché rather nicely.

And it seems to be true – sitting at that round table with FFT, he doesn’t try to be charming (he isn’t even particularly friendly) or come across as suave. But he obviously calls the shots. And it’s also telling that the man sitting between him and Zorc, the marketing director Carsten Cramer, hardly gets a word in. If these three men want to transport the message that Borussia are not a business but still a good old-fashioned football club, then they are doing a neat job.

“Having young players extends your credit limit with the fans”

But the business aspect is important. Money is vital – and who would know this better than these men, whose club learned the hard way what happens if you don’t keep an eye on the balance sheet?

“In only 18 months, we cut our budget from €57m to €24m,” says Watzke, who was brought in to save the club. “The problem was that people still thought of us as a Champions League club and that 75,000 or so came to watch the home games. But we didn’t have the team anymore to meet these expectations. The older players were mentally already on the hop, looking for new clubs.”

These were difficult years for the club and their massive support. (The mythical terrace, the South Stand, holds 24,500 people alone, almost all of whom have season tickets. Dortmund now have the highest average attendance in European football – 80,645 per home game – but even in the worst years following the near-crash, the average attendance never sank below the 70,000 mark.)

Watzke and Zorc will also readily admit that they made “a few mistakes as regards the coaching job” – there were three gaffers in the 2006-07 season alone. And yet the seeds for success were sown precisely during this period.

“We sat down and first had a look at the status quo,” explains Watzke. “Then we asked ourselves: what is it people expect in this part of the country, the working-class Ruhr area? The answer was that they expect an honest effort and that you give your all. So that informed our new philosophy. We defined the brand as: real and intense. The football should be intense, while we should be real.”

To that end, Borussia began to offload experienced, overpaid players and started signing young and hungry talents. Zorc, who found most of these players and brokered the deals, admits that “this had economic reasons, too” as expenses had to be cut drastically. But it also fitted the new maxim to go with youth.

Dortmund were the first German club to do this on a larger scale, perhaps also encouraged by the unexpected success then-national coach Jürgen Klinsmann was having with putting faith in young, untried players.

In a way, the club were at the right place at the right point in time and benefiting from another, earlier disaster. Germany’s dismal showing at the European Championship in 2000 had led to a complete restructuring of the country’s youth set-up, with centres of excellence springing up everywhere and clubs being forced to invest heavily in their facilities.

On the one hand this was a problem for Dortmund, as the club had postponed the fulfilment of this requirement for so many years (preferring to spend the money on players’ wages) that Watzke was given an ultimatum – build a modern training complex or risk relegation as punishment – just when money was tightest. But on the other hand, it was a godsend because after years and years of talent dearth, there were suddenly promising kids coming through when Dortmund needed them the most.

Naturally, youth is not a quality in itself. Dortmund found kids who could not only play a bit, but were also budding Monsters of Mentality. Four years ago, for instance, Zorc decided to sign a then-20-year-old midfielder from the second division by the name of Kevin Grosskreutz. He was pretty good, but not supremely talented. The main reasons why Zorc targeted Grosskreutz were that the player was a tireless runner and almost pathologically passionate about the club.

Grosskreutz, you see, was born in Dortmund, used to play for the club’s youth teams as a boy and even carried a season ticket for the terraces. Whatever his shortcomings, he was a perfect embodiment of the new Borussia. “Having young players extends your credit limit,” Watzke says with a smile, relishing the play on words. “But not with banks, as in the old days. With supporters! In 2009, the average age of the squad was 22. If these players make mistakes, the fans will forgive them.”

All that talk about what the fans want is not mere lip service – not at Dortmund, not in Germany in general. Again, many of the things you may have heard are indeed true. Yes, you can watch your team from the standing areas with a beer in your hand; yes, the tickets are comparatively cheap and the atmosphere is usually excellent; yes, highlights of the games are shown on public television an hour after Saturday’s matches have ended. But these things haven’t been granted by benevolent clubs or associations. They still exist because the supporters have fought for them.

It may be a Teutonic characteristic, but somehow German fans have the knack of organising themselves and creating pressure groups. While FFT was in Dortmund, for example, the fans kept utterly quiet – no singing or chanting whatsoever – during the opening stages of the games as a protest against proposed new safety measures.

And they did that at every ground in the professional game! This spectacle made you understand why Borussia don’t have just the one supporter liaison officer we met in La Manga but no fewer than five of them.

However, there can be a downside to fan power. We were early for our meeting with the club’s top brass in Dortmund and thus took a walk around the building that houses the club’s headquarters. On the ground floor, there is a merchandise store. Somebody in a white protective suit was about to clear the windows, because they had been attacked with paint bombs overnight.

The interesting thing was that the perpetrators had been careful not to stain any other part of the building – just the merchandise store – and that the paint balls were black and yellow, Dortmund’s colours. Clearly, the message was that the club’s own fans had done this to protest against... well, who knows? The projected new league regulations, maybe (which could lead to a reduction of the number of tickets allocated for away fans), or perhaps the commercialisation of the game.

It’s a sensitive issue, particularly for a club which seeks to be intense and real yet has to earn money. Maybe that’s why Cramer, the marketing man, is so quiet during our talk with Dortmund’s leading executives. “We are only a side issue here,” he says at one point, meaning the salespeople. “This is a football club and these gentlemen exemplify that,” he adds, meaning Watzke and Zorc.

Still, in his own way Cramer is just as important as the other two. He came up with the motto that now adorns a lot of the club’s merchandise – Echte Liebe, ‘Real Love’ – and has been very supportive of FFT’s idea to profile Borussia, knowing very well that there is a huge market waiting to be conquered and that there are many things about his club, from the tradition and the support to the coach and his team – that make Dortmund an attractive proposition for a foreign audience increasingly disillusioned with the modern game.

“We have made some fundamental decisions to do with things that we consider part of our football culture,” says Watzke. “We forgo between €4.5m and €5m every year because of terracing, but it’s part of who we are. We have decided to always play in black and yellow [their second kit includes the same colours]. We have decided to not shut off the team from the world, which is why we have training sessions that are open to the public. And even though Mr Cramer felt slightly different about this, we decided not to open a merchandise store on the training complex.”

The under-9s alongside the Bundesliga side

The day after this meeting, we sit down with the team’s long-time captain Sebastian Kehl at said training complex – the one Borussia was forced to build at the height of the club’s financial problems. Until the late 1990s the area, which covers 180,000 square metres, was used by the British Forces.

There are now six full-size pitches and two smaller ones, on which each of the club’s many teams train, from the under-9s all the way up to the Bundesliga side. (“We want the little boys to be able to watch their idols,” says Watzke, “because this is what ‘real’ means.”) There are also two larger buildings and one annex. This is where FFT meets the captain, because this is where the Footbonaut is.

The Footbonaut (as seen in FFT Performance in January) is a training device invented by a creative mind from Berlin five years ago. Dortmund are the first club in the world to use it regularly. It looks like one of those bare, surreal rooms you might know from the horror film Cube, but in fact it’s a highly sophisticated ball machine – you have to properly trap a ball that’s coming at you and then quickly put it into a certain place. The hard part is that you don’t know where the ball is coming from or where it should go to until the last moment.

You wonder what Kehl is thinking, standing in this hi-tech gadget, on this state-of-the-art complex, and meeting an international magazine that wants to know why Borussia are taking Europe by storm, just eight years after nothing less than the club’s survival was at stake. He remembers these days better than most, because nobody has been at the club longer. The 32-year-old holding midfielder is now in his 12th season for Borussia, the only outfield player who has lived through the near-bankruptcy, the youth movement and Klopp’s total-effort revolution. Which means he’s in a better position than anyone else to explain how Dortmund managed to come back from the brink stronger than ever before.

“We had a clear idea of where we wanted to go,” he says, “and everybody pulled together, from the fans to the sponsors. Then Klopp put that new philosophy into practice, with many young and talented players who’ve developed fantastically.”

It’s a testament to Kehl’s status somewhere between elder statesman and club icon that Dortmund never got rid of him, not even when Klopp introduced a style better suited to younger legs. “Thanks to Klopp, I have learned a new way of playing the game,” Kehl says. “But I have always been known as a player who covers a lot of ground and who defends aggressively, so I guess the system suits my skills.”

Perhaps the real question is not why he wasn’t let go but why he chose to stay. After all, many regulars toyed with moving when money became scarce; they were “mentally on the hop”, as Watzke put it. “I felt at home here,” Kehl explains.

“Over time, the club has become close to my heart and it has given me a lot. Emotion, honesty – they live that here. When the club had problems, I felt an obligation to give something back.” And then, as his eyes wander over to the Footbonaut, he gives you an unprompted answer to the question of what he’s thinking when he sees all this.

“I’m happy that I was rewarded for it,” he says. “In sports, there are always ups and downs, but I guess what I’ve experienced here over a short period of time is unusual. That’s why it’s awesome to have this success now. It makes me proud.”

The man who made it all happen, who is most responsible for the success, was a defensive midfielder with far more brains and commitment than talent, who played 325 games in the second division for a small, unfashionable club called FSV Mainz. In 2001, when he was only 33, he was promoted from the playing staff to the coaching job. Over the course of the next seven seasons, he not only took the club to the Bundesliga for the first time in Mainz’s history but kept the team there against all odds for three years.

“The reason we decided to sign Jurgen Klopp was this Mainz team,” says Watzke. “They weren’t Real Madrid, but they were unpleasant opponents. They had a plan, they had an enormous will and they always seemed to have more players on the pitch than you did. We felt that the man who had created this team spirit and this mentality could also do it for us.”

In the summer of 2008, Dortmund signed Klopp, whose contract at Mainz had run out and who was looking for a new challenge, a bigger club. Watzke later said he knew he’d made the right decision on Klopp’s first day on the job. During the initial press conference, the coach said he couldn’t promise titles but he would promise what he termed “full-throttle football”. Then he told the journalists that “if games become boring, they lose their right to exist” – and Dortmund never looked back.

It’s true, there hasn’t been a single game in the four-and-a-half years since that day that left the fans feeling the team hadn’t done everything it could do (and then some). To say that Klopp is revered and his players are popular in Dortmund would be an understatement.

We’re talking more about something like Echte Liebe here, real love, especially since a wholly unexpected but thoroughly deserved Bundesliga title in 2011 was bettered 12 months later by the first league and cup double in the club’s long history. And even though the Empire is striking back domestically (Bayern are running away with the league title this season), Borussia still continue to become better and better, as a surprised international audience has witnessed on the biggest stage of them all this season.

“To be honest, we were a bit surprised that people abroad are so surprised,” says Zorc. “Of course we never expected to win this tough Champions League group so convincingly. But we learned a lot last season, when we didn’t do so well in Europe.

"And we knew that the problem had nothing to do with lack of quality, because we had won five competitive games in a row against Bayern Munich, who were good enough to reach the Champions League final. So we were convinced all along that we were among the 10, 15 best teams in Europe.”

Ask what the problem was and you get many different answers, or maybe just different aspects of the same thing – experience. Watzke and Zorc say the young team had to adapt to a totally different “quality of football”.

Striker Lewandowski says: “We don’t make as many mistakes as we did last season.” Reus says: “This season we don’t create as many chances as the team did last year – but we take them better. That’s how you win games.”

The man who should know best strokes his beard, leans back in that comfortable hotel armchair and says: “Our defensive pressing has improved. We are now more straightforward and precise, even if we have to defend deep. That used to be a problem in the past, when we always tried to attack early, far upfield. But that isn’t always possible against strong opposition, so you have to know how to defend deep and then use the space in front of you.”

Klopp goes on to explain that his team learned this alternative approach not so much in Europe but rather in the domestic games against the mighty Bayern. “It’s this turnover game that has made us into a top team and helps us in the Champions League.” In layman’s terms, his enthusiastic kids who love to run so much are now playing it smart, too.

More top players will be lured to Germany

Where all this will lead is anybody’s guess. Told his team are considered dark horses for the Champions League, Klopp calls that “claptrap” and points out how strong their last 16 foes Shakhtar Donetsk are (“as English audiences will have seen”). Then he says: “I understand why people are saying that, considering how well we’ve played. But a few good games don’t make a Champions League winner.”

Yet one should not underestimate the club’s ambition. In the summer, Dortmund parted with more than €17m to bring Reus back to the club he left in 2006. It was the club’s biggest transfer since 2002 and it signalled not only that Dortmund’s financial health is more than just robust again, but that the club intends to go places.

Watzke says: “Our stated aim is that the German game will not have one but two lighthouses by the year 2020 and that the second one will not be red and white [Bayern’s colours, of course], as lighthouses usually are, but black and yellow.”

The players are very much aware of this; they know they are with an upwardly mobile club. “The club has really been transformed since it was on the brink a few years ago,” says Reus, “and we haven’t yet reached the end of the line. A lot is possible. Now that the foreign clubs can’t invest as much as they used to, the focus will be more and more on the German game. More and more top players will be lured to Germany because our clubs have kept their financial house in order.”

This is a forecast you hear everywhere these days. Sports business experts like the Frenchman Emmanuel Hembert, who works for the global management consultancy AT Kearney, predict a major comeback for the German Bundesliga on the European stage, particularly once UEFA’s Financial Fair Play concept kicks in.

As Zorc tells FFT, he is suddenly getting calls from Spanish and Italian agents trying to place their clients with German clubs who, in Zorc’s words, wouldn’t have been considered “chic enough” a few years ago.

Which is also why Dortmund aren’t too afraid of losing their best players. Lewandowski is probably the next to move to England, that’s true, but many in the squad have signed long-term contracts and, well, want to play for Klopp too much. Which raises the obvious question. What if Klopp goes?

“We rule out this possibility until 2016,” Zorc says matter-of-factly, while Watzke has an even more unusual answer: “We promised each other to see this thing through. I know this is rare in football, but that’s the way it is.”

The man who’s promised to ‘see this thing through’ rises from his armchair and leaves the lobby in La Manga. Not to retire for the night, though.

There’s still the matter of the exclusive photo shoot for FFT. And it is here, in this strange setting, that you realise the unusual bond that exists between him and his players.

With growing enjoyment, he watches the men he calls his ‘boys’ being photographed, yelling encouragements, cracking jokes, giving instructions, needling the footballers until they grin into the camera. It’s almost as if he’s assisting the photographer. Then Klopp is asked to step forward and strike a certain pose, pointing into the distance.

“It would be good if you yelled something,” suggests the photographer. “Just to make it more lifelike. It doesn’t matter what it is – the first thing that comes to your mind.” Klopp takes his stance, raises his arm, points his finger and then yells... “RUN!”