How Brighton went from the brink of extinction to the Premier League – told by their heroes

Almost 25 years ago, Brighton were on the edge of oblivion. After two decades of hard work and heartbreak, they're now a Premier League staple – and they could go top with a win over Crystal Palace...

An edited version of this Brighton feature originally appeared in the September 2017 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe!

There were 28 minutes remaining at Edgar Street, and hope was starting to evaporate. Brighton & Hove Albion were losing 1-0 at Hereford on the final day of the Division Three season. Homeless, they were heading for non-league.

Fans huddled in the packed Blackfriars End terrace were bracing themselves for the worst – not just relegation, but possible oblivion. The Goldstone Ground had been sold from under them. After 96 years of existence, it looked like the end – thanks to an own goal from Kerry Mayo, a boyhood Seagull in his debut season as a pro.

“If I’d had time to think about it, I would have tried to place it and probably missed,” Robbie Reinelt tells FFT over 20 years on, recalling the moment he came off the substitutes’ bench to carve a place in Brighton history. “Craig Maskell’s volley rebounded off the post, and in that split second I just hit it. The supporters went absolutely crazy. Kerry jumped onto my back and told me, ‘You’ve just saved my f**king life.’”

Reinelt’s goal was enough to give Brighton the point they needed, as the fourth tier’s bottom two clubs went head-to-head in a dramatic shootout for Football League survival. That day in 1997, Brighton survived, Hereford went down. Today, they stand five divisions apart: Hereford in the Southern Premier League, Brighton in their fifth season in the Premier League.

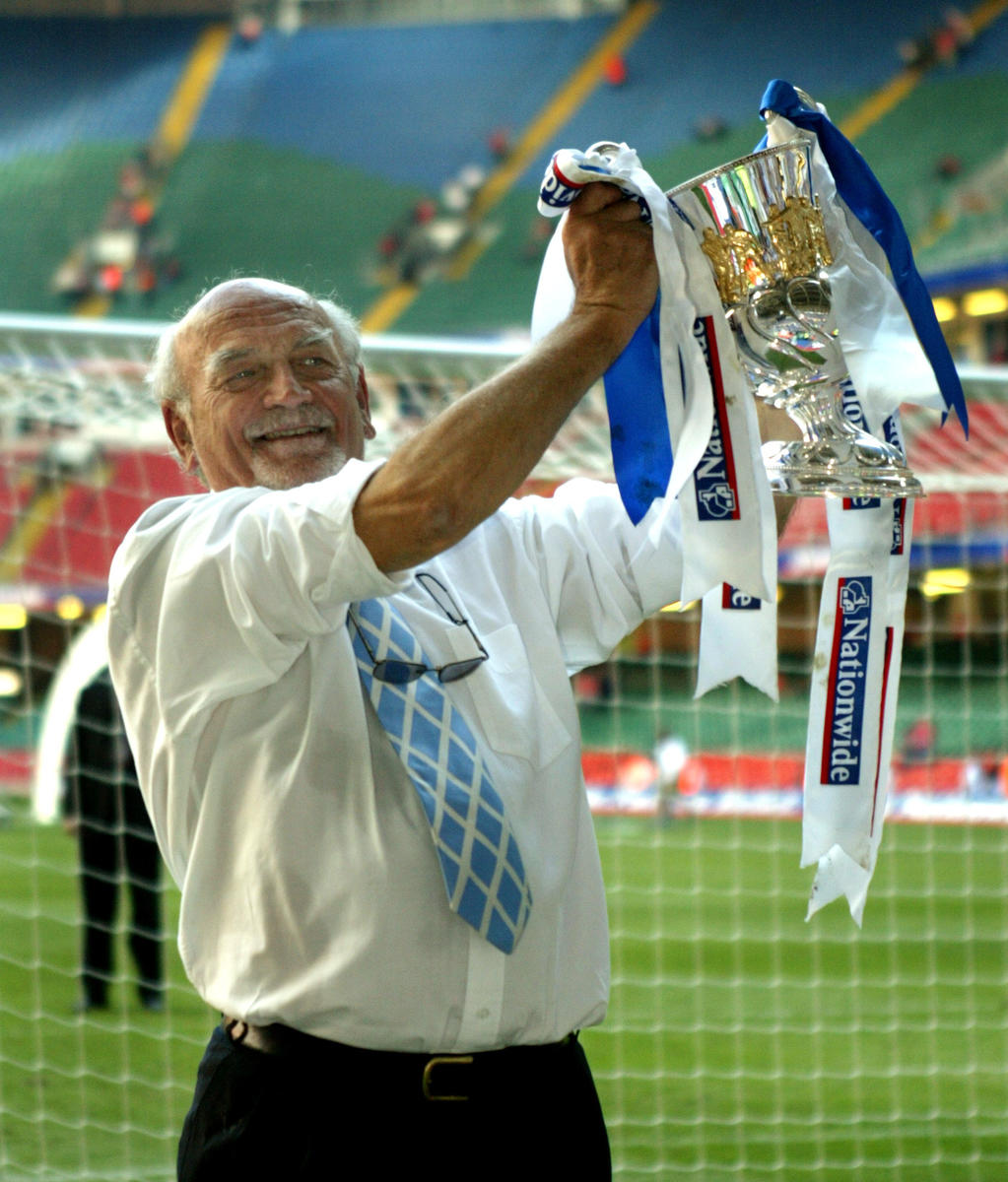

“We make any player we sign very aware of the history of this club,” Chris Hughton told FourFourTwo during his tenure as Brighton manager, during which he guided the team into the top flight in 2017. “We’ll show them a video of the history – from where the club were, to where we are today.”

“We could get to the Champions League and every supporter who was around in those days would still tell you the Hereford game was the single most important game in Brighton’s history,” says lifelong Seagulls fan Alan Wares. “If we’d lost, there would be no Brighton & Hove Albion any more. We wouldn’t have been accepted into the Conference as we had no home.”

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Head a mile up the hill from the seafront in Brighton and you'll find a reminder of where things went so badly wrong for the club. It’s a nondescript retail park with a Nando’s, the sort that you will see in countless towns and cities up and down the country. This one is different, though. Wander to the other side of the main road and an information board details the site’s significance. This used to be the Goldstone Ground.

“Many of us try to avoid driving past it,” says Paul Samrah, one of the most significant fans in Brighton’s rise back to prominence. “My wife thinks I’m crazy but we’ve all got our idiosyncrasies and that’s mine. Even now, all these years on, it’s still too painful.”

Brighton were in the FA Cup final in 1983, but 12 years later they were in the third tier and experiencing financial issues. The news still came as a bolt from the blue: the club were set to sell the Goldstone.

“Sure, the club were in a bit of a pickle but they didn’t have to sell the ground,” Wares insists. “If they had wanted to restructure the finances, they could have done so in a way other than the nuclear option.”

Brighton were to leave the stadium at the conclusion of the 1995/96 campaign, destination unconfirmed. Portsmouth’s Fratton Park seemed the most likely, but all that was known was that the club were departing Brighton, with no concrete plans for when they would return.

Unhappy with owner Bill Archer and chief executive David Bellotti, anger among fans snowballed when it emerged that an important section of the club’s constitution had been changed – with the removal of a clause that prevented shareholders profiting from asset sales if the club folded. The clause was later reinstated, its omission described as an oversight, but by then the relationship between board and supporters was irreparable. Samrah and his fellow fans formed the Brighton Independent Supporters’ Association, and protests grew.

Meanwhile, the team were busy getting relegated to the fourth tier. They were already down when they faced York in their final home match of 1995/96 – what looked to be their final game at the Goldstone. More than 1,000 fans invaded the pitch, protesting right in front of the directors’ box. Supporters broke both crossbars, forcing an abandonment, with the match later replayed on a Thursday morning.

“When the game was abandoned I thought, ‘This is a moment’,” Wares says. “It was absolutely necessary. We were screaming and no one was listening.”

He adds, with a shake of the head, “The FA was more focused on Euro 96.”

More than 1,000 fans invaded the pitch, protesting right in front of the directors’ box. Supporters broke both crossbars, forcing an abandonment

“Liam Brady called it ‘a different kind of riot’ – that was a really good quote,” continues fellow supporter Steve North, an actor in London’s Burning who would later co-write two books about the team. Brady had managed the club, departing in 1995 because of disagreements over the way it was being run. A day after the York abandonment, he stood outside the Goldstone offering to put his own money in as part of a consortium to take over the club, but it was met with resistance from the board.

The pitch invasion brought a suspended three-point deduction, to be enforced if it ever happened again. In the end, it turned out not to be Brighton’s final game at the Goldstone, with the club granted a one-season extension before the bulldozers moved in.

The 1996/97 campaign brought more protests – at matches; at Archer’s Focus DIY stores; even in his home village in Lancashire – while some of the games were boycotted.

“We were boycotting against Mansfield but someone managed to get the gates open to one of the disused stands and we piled in – suddenly there were 2,000 of us on this terrace,” chuckles North.

The pitch invasions continued. When the fans ran on once more against Lincoln, the FA deducted Albion two points, leaving them 11 points off safety after a nightmare start.

Relegation to non-league appeared inevitable but the December arrival of Steve Gritt – formerly joint-manager with Alan Curbishley at Charlton – revived their form. They didn’t lose at home again for the rest of the season and beat Hartlepool 5-0 on Fans United day, with supporters from approximately 65 other clubs – which included Eintracht Frankfurt and rivals Crystal Palace – stood shoulder to shoulder with Brighton fans and their cause.

The protests finally persuaded Archer to sell up late in the season – to Dick Knight, Brady’s original backer – but there was no saving the ground. The final game there came on April 26, 1997, when Brighton beat Doncaster to move off the bottom of the league for the first time in 203 days, ahead of the Hereford showdown. The club would spend the next two campaigns playing at Gillingham – some 70 miles away.

Lewis Dunk knew the celebrations would be raucous, but he was not quite prepared for all this.

“I got off the pitch wearing just my pants,” the defender laughs.

“When the final whistle went, the fans poured on and within a few seconds I was mobbed. I gave my shirt away to somebody, then someone else started ripping my shorts off! I said, ‘Don’t rip them off, I’ll just give them to you!’”

This was an invasion for all the right reasons. Almost 20 years to the day since that final game at the Goldstone, the Seagulls had won at home to Wigan, effectively securing promotion to the Premier League – even if mathematical confirmation came a couple of hours later when Huddersfield drew at Derby.

I gave my shirt away to somebody, then someone else started ripping my shorts off! I said, ‘Don’t rip them off, I’ll just give them to you!’

“It was a great day,” smiles midfielder Steve Sidwell. “We came out of the stadium with the fans and we had a private function in town – there were no taxis so we thought, ‘Let’s get on the train with all the fans’. They loved it, we loved it – some players were crowd-surfing on the train! They’re memories that we’ll never forget. I’d been promoted to the Premier League before at Reading, but those celebrations were nothing like this.”

The heightened celebrations were understandable – Bournemouth, Swansea and Burnley had previously reached the Premier League after narrowly avoiding relegation to non-league, but even they hadn’t faced the devastation of losing their ground as well.

Newcastle pipped Brighton to the title, but it didn’t matter. “We had a parade and fans of other clubs said, ‘You’re having a parade for finishing second?’” Wares says. “No, we were having one for the previous 20 years.”

On the day Brighton reached the Premier League, Reinelt was watching from afar with a smile. “They’re back where they should be,” says the hero of the Hereford game, now a track maintenance man for Network Rail. “I’m proud to have played a part, although I feel awkward when people say I’m a legend. I went to an event recently and Brian Horton was there who played for the club for years, yet there was me who scored a handful of goals, and they were classing me as a legend. It’s weird but I’m proud, of course.”

The mood around Brighton has been transformed since the club’s darkest days – something Dunk has seen for himself, having grown up in the city. “My dad has told me about the Goldstone – he used to sneak into the North Stand without his dad catching him,” says the 25-year-old. “I was a Chelsea fan. If you drove around Brighton a few years ago, you wouldn’t have seen a Brighton shirt. There’d be no kids in Brighton shirts in the park. Now all you see is kids in Brighton shirts. The club’s improved so much.”

If you drove around Brighton a few years ago, you wouldn’t have seen a Brighton shirt. There’d be no kids in Brighton shirts in the park. Now all you see is kids in Brighton shirts

The Seagulls would return to Brighton at the Withdean Stadium in 1999, but not before more tribulations.

Even after avoiding the drop against Hereford, there was another scare in the summer of 1997, when the Football League voted on whether to expel the Seagulls. Although Dick Knight’s takeover had been agreed, it had not been finalised and Albion were yet to lodge a £500,000 bond confirming they’d fulfil the next season’s fixtures. Seventeen clubs voted to kick them out of the league, but 47 backed them. Eventually the takeover was completed – and Knight is regarded as a hero in Brighton for saving the club.

He soon began his quest to return the Seagulls to the local area – in the interim, the Gillingham groundshare meant a depressing journey along the M23, M25, M26 and M20 every couple of weeks. “We used to call it four motorways and a funeral,” explains Samrah. The crowds dipped to an average of 2,300.

“It was absolute bollocks,” says John Baine, a Brighton-supporting punk poet who introduces himself by his stage name of Attila the Stockbroker. “We were playing home matches 70 miles away with the worst team that we’ve ever had – even worse than the previous season. The only reason that we didn’t get relegated [in 1997/98] was because Doncaster were even worse.”

Attila had been a co-founder of Albion’s Independent Supporters’ Association and operated the PA system at the Priestfield. “We were playing Colchester on Boxing Day and to liven things up I decided to play Anarchy In The UK by the Sex Pistols,” he says. “It was on for about a minute and a policeman burst in and said, ‘Take it off, take it off, you can’t play that!’ I said, ‘Why not?’ He was livid. He said, ‘It’s obvious, it incites violence in the crowd!’

We were playing Colchester on Boxing Day and to liven things up I decided to play Anarchy In The UK by the Sex Pistols. It was on for about a minute and a policeman burst in and said, ‘Take it off, take it off, you can’t play that!’

“I looked at him and then said, ‘Well officer, I bought Anarchy In The UK in 1976 and never once has it made me think of being violent, but every time I hear In The Air Tonight by Phil Collins I turn into an axe-wielding psychopath. He didn’t laugh – I was banned from doing the PA. Dick Knight got in touch with the police and it was rescinded on condition I didn’t play Anarchy In the UK again. I played Smash It Up by The Damned and I Fought The Law by The Clash instead...”

Fortunes on the field began to pick up after the move to the Withdean, an 8,000-capacity athletics stadium on the outskirts of Brighton. With some temporary stands brought in from the Open Championship golf and a roof on only one side, luxury it wasn’t – but it was a home, and that was all that really mattered.

“Compared to Gillingham, the Withdean was paradise,” Wares says.

Bobby Zamora led the Seagulls to two successive promotions, before a young Steve Sidwell turned up on loan from Arsenal. “It was all very different back then,” Sidwell says of his first spell at the club, in 2002/03. “We were training over at the university and then taking the kit home to wash ourselves.”

The club’s aim was to build a new stadium they could truly call their own, but it took a lot longer than they’d ever imagined. Lewes District Council opposed plans for a stadium in Falmer in the east of the city, with concerns it could affect the beauty of the surrounding Downs. Cue a public inquiry overseen by the Deputy Prime Minister John Prescott, who gave the stadium the go-ahead – only for an error in his report to lead to a challenge from the council, controlled by the Liberal Democrats, and two more years of delays.

The supporters campaigned tirelessly over many years and formed the Seagulls Party, with Samrah & Co. organising various inventive schemes to keep the plea in the public eye – including sending Prescott a bouquet from every club in the country.

If Busted hadn’t split up that same week, the ugliest load of punks you’ve ever seen would have been appearing on Top of the Pops

“It was hugely time consuming – we would be up until 3am, then getting ready for work at 6am,” Samrah explains of those days in the thick of the Falmer For All campaign. “But would I do it again? Yes. It was all fun – it really was.”

Fans even had a top 40 single – a Falmer protest version of Piranhas hit Tom Hark, which climbed to No.17 in the charts with help from Skint Records, the label behind Brighton’s very own Fatboy Slim. “We got incredible publicity out of it,” says Attila the Stockbroker, who wrote the new lyrics. “And if Busted hadn’t split up that same week, the ugliest load of punks you’ve ever seen would have been appearing on Top of the Pops.”

Eventually, the stadium campaign succeeded. “I remember going on one of the marches for the stadium with my family when I was young,” says Dunk, who was part of the club’s youth system during the Withdean days, before becoming a first-team regular in the first campaign at the impressive new Amex Stadium.

“The stadium was a massive boost for the club. No one wanted to play at the Withdean, although it worked both ways – we didn’t want to be there, but the opposition didn’t want to be there either. With the running track, the away supporters were about 200 metres away from the pitch – you couldn’t hear them, and they probably couldn’t even see the game!”The first ever league encounter at the Amex, in August 2011, was a victory over Doncaster – just as their final match at the Goldstone had been. “Like most of the blokes over the age of 40, I blubbed my eyes out,” Wares recalls of that day six years ago.

Current owner and Brighton fan Tony Bloom – a property investor and professional poker player who goes by the nickname ‘The Lizard’ – did much to fund the stadium as well as a huge, state-of-the-art training facility, which would be the envy of many other clubs already established in the Premier League. In the main, though, money has been directed towards infrastructure rather than large transfer fees.

“Some clubs do it the wrong way – they put a lot of money onto the pitch first, try to get success there and build around that,” says Sidwell. “Here it has been done in the correct way.”

“He’s been a wonderful chairman to work for,” says Hughton, who has stayed within his budget to produce a talented and cohesive side. “In this day and age, when everything seems to have gone crazy in the transfer market, we have had a very level-headed chairman.”

Glenn Murray was another to play for the club at the Withdean, and was taken aback when he returned for his second spell with the Seagulls in 2016.

“It sounds stupid, but it was almost like coming back to a brand new club with the same badge and same name,” the striker told FFT in 2017. “The club has grown at such a rate. We were in the League One relegation zone in my first spell, but Gus Poyet took over and the season afterwards we got promoted. The club owes Gus a lot.”

This all seems worlds away from Gillingham and those final days at the Goldstone.

You look around now at the 30,000 crowds and think, ‘Bloody hell, this is what we have created’. Out of the depths of despair, it shows you what can be possible. If everyone works together, it’s amazing what you can do.

“They used to say: ‘How are you going to fill your new stadium when you are only getting 5,000 at the Withdean?’” Attila says. “But I remember a Tuesday night game against Rochdale in the ’70s in front of 25,000. I would say, ‘Just you wait and see.’”

“This is our reward," adds Samrah.

“You look around now at the 30,000 crowds and think, ‘Bloody hell, this is what we have created’. Out of the depths of despair, it shows you what can be possible. If everyone works together, it’s amazing what you can do.”

On the day of Brighton’s final match at the Goldstone, Attila the Stockbroker sat down and penned a little poem.

“And one day, when our new home’s built, and we are storming back, A bunch of happy fans without a care, We’ll look back on our darkest hour and raise our glasses high, And say with satisfaction: we were there.”

Nearly 25 years on, that excerpt could not have been more prophetic.

Restock your kit bag with the best deals for footballers on Amazon right now

Subscribe to FourFourTwo today and get three issues delivered for just £3. The offer ends October 17, 2021.

ALSO READ

WHO'S THE BEST? FIFA 22 player ratings: Top 100 players revealed

NEW FEATURES What is Hypermotion? Everything you need to know about EA Sports' gameplay explained

FIFA 22 Everything you need to know about FIFA 22's new features

Chris joined FourFourTwo in 2015 and has reported from 20 countries, in places as varied as Jerusalem and the Arctic Circle. He's interviewed Pele, Zlatan and Santa Claus (it's a long story), as well as covering the World Cup, Euro 2020 and the Clasico. He previously spent 10 years as a newspaper journalist, and completed the 92 in 2017.