Brothers in armed conflict: Why Dinamo Zagreb vs Hajduk Split is more than a game

After the break-up of Yugoslavia, Croatia's big two quickly settled into mutual loathing... from the March 2007 issue of FourFourTwo

It’s like a scene on the French Riviera. Expensive yachts, drenched in sunshine, bobbing up and down in the bay in front of the palm tree-lined promenade, with its packed cafes and their overworked espresso machines. But this isn’t the Cote d’Azur, it’s the Riva in Split, Croatia, a cheaper, less pretentious version of France’s Mediterranean coast.

Take a closer look at the people sipping cappuccino and sparkling water and you’ll notice that an inordinate number are wearing football shirts: Hajduk Split shirts to be precise. From pensioners walking their dogs to babies in prams, the crisp white jersey with the club’s distinctive red-and-white chequered crest is everywhere.

Not many of the people enjoying their Sunday afternoon on the Riva will be going to tonight’s match, however. Instead, they’ll be watching on the dozens of big screens that the cafes have had specially installed – it’s the safest place to be when Hajduk take on their bitter rivals Dinamo Zagreb.

Five hours before kick-off, 500-plus fans are already gathered, drinking beer, lighting flares and burning blue shirts

A five-minute walk in the direction of Hajduk’s Poljud Stadium shows why. The Stari Plac is the club’s old ground and today houses the headquarters of the Torcida, Hajduk’s hardcore supporters. The contrast with the atmosphere on the Riva couldn’t be starker. Five hours before kick-off, 500-plus fans are already gathered, drinking beer, lighting flares and burning blue shirts with the letter ‘D’ on them.

The singing is loud too, though there’s little variety, the words “f**k”, “Dinamo” and “Zagreb” appearing in virtually every chant. A donkey draped in Hajduk colours is paraded around the sweaty, beer-sodden street, as fans cheer and maul the poor animal like a stripper at a stag party, yet despite the raucousness, there are few police present – the majority are at the stadium, awaiting the arrival of 2,000 Dinamo Zagreb supporters.

FourFourTwo asks one Hajduk fan if he’s expecting trouble. “Yes,” he says hopefully, “I think so”, and given the recent history of this fixture, his optimism is well founded. Few derbies in the Balkans, arguably anywhere Europe, are as explosive as Dinamo versus Hajduk, with violence marring every single match. But it wasn’t always so…

The Split

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Slaven Bilic is in an awkward position. As head coach of Croatia, the former Everton and West Ham defender has to be diplomatic about the biggest match in the domestic calendar, but given that he joined Hajduk at the age of nine, it’s not easy.

Hajduk-Dinamo games were like a big celebration. It was the only chance Croats had to make an expression of our nationality. The fans sang the same songs, it was fantastic

That said, when Bilic played against Dinamo before the break-up of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s, matches between Croatia’s two most successful clubs were one big, patriotic, love-in. “The games were like a big celebration,” explains Bilic, in his intriguing half-Scouse, half-Cockney English accent. “It was the only chance Croats had to make an expression of our nationality. The fans sang the same songs, it was fantastic.”

Back then the enemy was Serbia and anyone and anything that emanated from Belgrade, particularly Red Star and Partizan. Indeed fans of Hajduk and Dinamo, in an expression of allegiance with their Croatian ‘brothers’, would often attend each other’s matches if they were playing opponents from the Yugoslav capital.

Supporters from both clubs enlisted in the Croatian Army and police, and fought and died in Croatia’s War of Independence between 1991 and 1995, while both sets of fans claim to have acted as a catalyst in the move towards civil war.

Early in 1990, with nationalist fervour simmering, Hajduk were at home to Partizan Belgrade. With 10 minutes to go, the hosts went 2-0 down. “At that time,” explains Bilic, “the mood in the country was very difficult. Yugoslavia was on the verge of breaking up and tensions were very high.

"After we conceded the second goal, hundreds of our fans broke down the perimeter fences and ran onto the pitch. They chased the Partizan players, but they didn’t beat them like many people said.”

For Red Star’s visit to Dinamo, violence seemed inevitable. Much of it was pre-meditated: rocks had been stockpiled, fans used acid to burn away security fences

Far more violent, and significant, was the match between Dinamo Zagreb and Red Star Belgrade on May 13 1990. For many, the events that day symbolised the start of the disintegration of the Yugoslav Federation. Two weeks earlier, Franjo Tudjman had been elected as President of Croatia on a fiercely nationalist ticket, vowing to lead the republic to independence.

For Red Star’s visit to Dinamo’s Maksimir Stadium, violence seemed inevitable. In fact, much of what happened seems to have been pre-meditated: rocks had been stockpiled, while fans used acid to burn away security fences. It’s widely believed that Red Star fans actually started the trouble by ripping up seats and throwing them onto the pitch, but when the Serb-dominated police force failed to take action, Dinamo fans invaded the pitch and running battles with the law ensued.

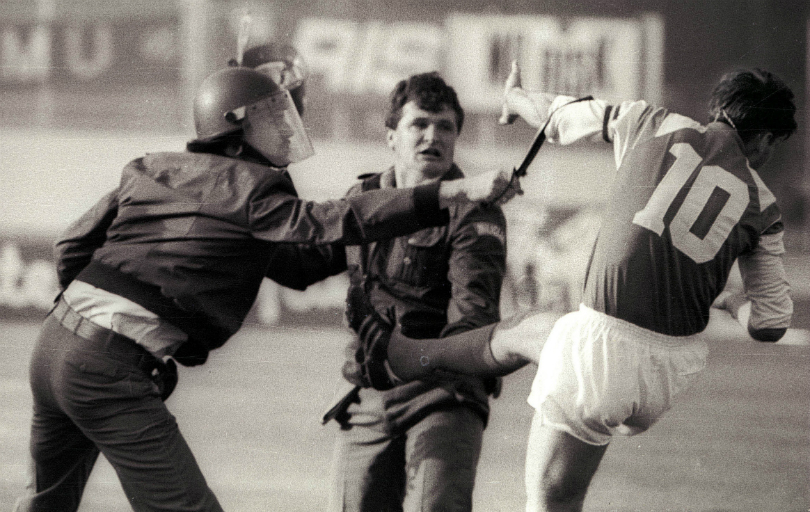

It was the best thing I’ve ever done. I had to defend our people and I wanted to fight the injustices that were being done that day. The frustrations that had built up for so many years just exploded

As the police laid into the Dinamo supporters, the players were enraged, none more so than Zvonimir Boban. Amid the chaos, the Dinamo captain simultaneously jumped up, kicked and punched a policeman before being dragged away. Red Star players had to be rescued from the rioting by police helicopters, while a total of 138 police officers and fans were injured.

Boban’s actions earned him legendary status in Croatia and a six-month ban from the Yugoslav national team, causing him to miss the 1990 World Cup, but he insists he has no regrets: “It was the best thing I’ve ever done. I had to defend our people and I wanted to fight the injustices that were being done that day. The frustrations that had built up for so many years just exploded.”

NEXT: From brothers in arms to bitter rivals

From comrades to enemies

After all they had been through as allies – on the football pitch and the battlefield – how did Dinamo and Hajduk become such bitter enemies? One theory suggests that after the break-up of Yugoslavia and the formation of independent football leagues, the two clubs were left with no obvious enemy, so a new rivalry had to be invented.

With Dinamo and Hajduk accounting for 14 of the first 15 Croatian championships, football was the obvious hook to hang it on, but very rarely does a rivalry based solely on football produce such bile and bitterness. Other factors are usually at work, and this case is no exception.

I pay my taxes here in Split and all my f**king money goes to Zagreb, that’s what p***es us off

“When Croatia became independent,” explains Split-based journalist Zdravko Reic, “Zagreb became the capital and we reverted to the old-style communist system of centralist government. So we went from centralist control from Belgrade to centralist control from Zagreb.

"If you want to get a good education you have to go to university in Zagreb, if you want to get a good job you have to go to Zagreb. I pay my taxes here in Split and all my f**king money goes to Zagreb, that’s what p***es us off.”

Socio-economic data would appear to back up Reic’s claim – nearly a quarter of Croatia’s 4.5 million population lives in Zagreb and unemployment there is low, whereas Split’s two major industries, tourism and shipbuilding, suffered immeasurably as a result of the war.

Reic’s final argument, though, takes some beating. “In 2005 Croatia hosted the World Beach Volleyball Championships,” he says, indignantly. “So, given that the Adriatic coast has some of the most beautiful beaches in the world and Zagreb is 100km from the sea, where do you think they hosted the tournament? In f***ing Zagreb! They took the sand from Split and flew it up to Zagreb – unbelievable!”

Unsurprisingly, the perception of centralist rule from Zagreb has also affected the politics of the national team. The President of the Croatian Football Federation is Vlatko Markovic, a former coach of Dinamo Zagreb, and the main reason why Croatia haven’t played a competitive match outside the capital since 1997.

Markovic is on record as saying the players prefer playing in Zagreb and, given that they’ve never lost a competitive match in the Maksimir Stadium (England being the latest victims), it’s a stance that is difficult to argue against. Even so, it irks the football-loving public of Croatia’s second biggest city.

To appease them, four months before Croatia were to take part in Euro 2004, the national team played a friendly against Germany in Split’s Poljud Stadium, but the Torcida asked locals to boycott the game and demanded the Federation start hosting some competitive matches outside Zagreb. Only 12,000 fans turned up at Hajduk’s 35,000-capacity stadium, but their demands continue to be ignored.

Journalist Dejan Bauer, a colleague of Zravko Reic based in Zagreb, offers an alternative view. “In Zagreb, we have a saying, ‘When it’s raining in Split, Zagreb is to blame’.” Bauer stops short of saying people from Split are lazy and have a chip on their shoulder, but the inference is clear.

In Zagreb, we have a saying: ‘When it’s raining in Split, Zagreb is to blame’

“Let’s just say Zagreb is near Vienna, everything is very organised and efficient, whereas in Split the people have a very ‘southern’ or ‘Mediterranean’ attitude.”

Slaven Bilic is one of the few people FourFourTwo meets who gives a balanced assessment. “Both Zagreb and Split are great cities,” he says. “Zagreb is more like London: it’s big, people are busy, always working and you never get to see your friends.

"I live on the beach in Split and my assistant coach, [former Derby star] Aljosa Asanovic, lives at the other end of town. It takes me six minutes to drive to his house. When you live in Split you can see your best friends four or five times every day. The two cities are just very different.”

Torcida vs Bad Blue Boys

The merit and commitment of Hajduk’s and Dinamo’s hardcore support is another major source of antipathy. Derbies are as much about the Torcida and the Bad Blue Boys as they are about the teams.

Few clubs, though, are as closely associated with their city as Hajduk Split. If you believe local folklore, only three things truly symbolise Split: the Marjan hills which overlook the city, the Diocletian Palace and Hajduk. Indeed, it’s impossible to walk through the streets for more than a minute without coming across graffiti relating to the club or the Torcida, both of which boast impressive histories.

The club was formed in 1911 by students returning from Czechoslovakia who had been blown away by the passion created by both Sparta and Slavia Prague and wanted their own team to support. Hajduk, named after a group of bandits who fought against Ottoman and Venetian rule from the Middle Ages onwards, won two Yugoslav league titles in the 1920s, but it wasn’t until 1950 that the Torcida were created.

So amazed were the Hajduk fans at the organisation and enthusiasm of Brazilian football fans at the World Cup that year, they named their own supporters group after them.

Like the Torcida gangs in South America, Hajduk’s fans were trailblazers. In their first year, they provided the team with Rio-style support for the title decider against Partizan Belgrade, the first time torches, banners and mass chanting had been seen in this part of Europe. Hajduk won the game and their third league title, but the football authorities were shocked at the frenzy of popular support on display.

The Yugoslav regime, which regarded Hajduk as ‘their’ club, were horrified that supporters could organise themselves in such numbers without the leadership of the Communist Party. In response, Torcida founder Vjenceslav Zuvela was given a three-year prison sentence and Hajduk’s captain was expelled from the Party.

Dinamo fans have also had their fair share of run-ins with the authorities, most notably in 1993 when club president Franjo Tudjman dropped the Dinamo name and re-branded them Croatia Zagreb. Tudjman’s thinking was that Dinamo was a communist identity and Croatia Zagreb could serve as an advert for his new country in prestigious European competitions. For such a skilled populist politician, the renaming of his, the capital’s and the country’s most popular club was a rare misreading of the public mood.

The Bad Blue Boys immediately launched a vociferous campaign to abandon the change. It didn’t happen until after Tudjman died in 1999 and his party was defeated in parliamentary elections a year later, but at the first game back as Dinamo Zagreb, the Bad Blue Boys celebrated by fighting police in the stadium.

The roof is leaking and we haven’t got the money to repair it. Dinamo fans get financial support from the mayor of Zagreb and local government

The Torcida’s HQ resembles a working mens' club: smoky, badly lit, a bar and pool table. “Look at this shitty clubhouse,” says Torcida member Ivan Pupacic. “The roof is leaking and we haven’t got the money to repair it.

"Dinamo fans get financial support from the mayor of Zagreb and local government. We rely on money from our members, and you know what, we prefer it that way, because when politics and sport mix it always ends badly. That’s what makes us real fans, not puppets for the politicians.”

Before long, the conversation inevitably turns to violence. “The Bad Blue Boys have a history of using knives, whereas we’re more old-school: we just use our fists.”

NEXT: They told Nico Kranjcar, "To us you're already dead"

Getting an alternative viewpoint is not so straightforward. “I can’t talk on the phone,” says Bogdan Urukalo of the Bad Blue Boys. “The cops will be tracing this line. And I can’t meet you in ‘Shit’ either. The police will be on our trail and you won’t be able to get near us. It’s best if you meet us somewhere outside the city before we head to the stadium. I’ll e-mail you.”

Three years ago, a convoy of Dinamo fans was ambushed by the Torcida. When Dinamo fans in one car refused to get out, flares were thrown inside, leaving them no option but to evacuate

Three hours before kick-off, FourFourTwo is in a quiet café in a sleepy village 20 miles outside Split. Inside, Bogdan and three pals are drinking coffee and smoking cigarettes. “This will have to be quick,” he says anxiously. “We could be attacked at any minute. We’ve hired cars with Split number plates so there’s less chance of the police trailing us, but you never know.”

Their fears are understandable. Three years ago, a convoy of Dinamo fans was ambushed by the Torcida. When Dinamo fans in one car refused to get out, flares were thrown inside, leaving them no option but to evacuate. Shocked and dazed, the four supporters were then badly beaten.

But if ambushing cars is an increasingly common tactic – and it is – so too is pre-emptive action by the police. Driving back from our pre-match meeting with the Bad Blue Boys, the news on the radio is that 20 Torcida members have been arrested and detained in dawn raids. They won’t be at the match tonight. Bogdan will and, in our brief interview, he sums up his thoughts on the derby. “They’re jealous of us. We’ve won more Croatian league titles than them and have more money than them.”

Crossing the divide

Dinamo’s superior financial muscle has often lured Hajduk’s best players to the capital, but the most notorious move between the clubs, in January 2005, saw Niko Kranjcar move the other way. Kranjcar was not just Dinamo captain, he was a product of their youth team and the son of famous Dinamo player and coach Zlatko.

When Nico Kranjcar joined Hajduk from Dinamo, the Bad Blue Boys lit 200 blue candles in a ‘D’ shape outside his home with a banner saying ‘To us, you are already dead’

It’s difficult to grasp how much of a stink his departure caused. The Bad Blue Boys told the midfielder, now with Portsmouth, that he’d never be safe walking the streets of Zagreb and, just in case he didn’t get the message, lit 200 blue candles in a ‘D’ shape outside Kranjcar’s home with a banner saying, ‘To us, you are already dead’.

Yet Kranjcar, who admits to “getting really caught up in the rivalry”, still believes the move was justified. “Dinamo had been playing badly for six months and everybody blamed me,” he explains. “I didn’t agree and I didn’t agree when they cut my salary. The vice-president then said I wasn’t wanted anymore, so what could I do? I could have moved to Russia but it was two years before the World Cup and I wanted to keep playing in Croatia.”

In Split, 10,000 Hajduk fans turned up at his unveiling and Kranjcar was an instant hit with the Torcida. Yet as he reflects on his days in Croatia, Kranjcar puts his finger on one of the more intriguing elements of the rivalry between Hajduk and Dinamo. “There’s too much violence and hatred,” he says. “We’re the same people from the same country – I don’t know why we can’t have the same goals in life.”

Familiarity breeding contempt

Strip away the mutual hatred, and the Torcida and the Bad Blue Boys are very similar creatures. One common theme is an alarming level of anti-Semitism and racism.

It should hardly come as a surprise given that 60 Croatia fans created a human swastika in the stands during a friendly against Italy last August, yet seeing the Nazi symbol daubed outside the Poljud Stadium and talking to members of the Torcida with ‘Eighty-Eight 88’ T-shirts on (the number represents the letters HH which means Heil Hitler) is still disconcerting.

And Dinamo’s supporters are just as bad. “Hajduk are Croatian nationalists, they’re right-wing, just like we are,” says Bogdan. “We don’t care for black people, Arabs, Jews or Serbs because thankfully they don’t live in our country.”

Dinamo were almost relegated two seasons ago, but it wouldn’t be the same without them. We just want to see them playing s**t

His comments back up the theory that the rivalry is formed out of necessity rather than a genuine mutual hatred. You can’t help thinking that if football reverted to an Adriatic League, as there is in basketball, comprising teams from the former Yugoslav state, the Serbs would return to being the enemy.

Until then, the Torcida and the Bad Blue Boys will have to be happy hating and fighting each other. Torcida member Ivan Pupacic even admits he wouldn’t want to see Dinamo relegated. “They were almost relegated two seasons ago, but it wouldn’t be the same without them. We just want to see them playing shit.”

With the best Balkan players playing abroad, interest in domestic football isn’t exactly flourishing in this part of the world and even derby matches can fail to live up to their billing. A week ago, Red Star and Partizan contested Belgrade’s ‘eternal derby’ in front of 21,000 fans, just half the capacity of the Stadion Partizana, while only 8,000 attended last season’s cup semi-final between the two sides.

But there are no such concerns 200 miles away in Split. Half an hour before kick-off, the 45,000 capacity Poljud Stadium is jammed solid. The only empty seats are either side of the 2,000 Dinamo supporters, flanked by two lines of heavily-armed police. The stadium is a sea of flags, flares and banners and the noise is deafening.

Slaven Bilic is watching the game with his nine-year-old son, Leo, from the safety of the VIP area, but there isn’t much to encourage the national team coach. It’s a scrappy affair, blighted by mistakes and play-acting. Hajduk look particularly nervous, and who can blame them? Their fans may be renowned for their loyalty, but it comes at a price.

When Hajduk lost a Champions League qualifier, fans broke into the stadium, dug 11 graves on the pitch in a 4-4-2 formation and left a banner saying ‘Be league champions or you’re dead’

The Torcida expect success. When Hajduk lost to Irish champions Shelbourne in a Champions League qualifier in 2004, fans broke into the Poljud Stadium, dug 11 six-foot deep graves on the pitch in a 4-4-2 formation and left a banner saying, ‘Be league champions or you’re dead’.

Tonight, the only players who seem capable of rising above the dross are Dinamo’s Luka Modric and Eduardo da Silva. Every time Brazil-born Croatia international Eduardo gets the ball, a chorus of monkey chants fill the air, but he seems oblivious.

Meanwhile, the rest of the players are more intent on fighting than winning. Seventeen minutes in, a couple of hefty challenges prompt a ruck involving all 20 outfield players. Seven minutes later, the match explodes again with Hajduk’s coach, Zoran Vulic, also getting involved. How nobody is sent off yet is anyone’s guess.

Then, on the half-hour, Hajduk take an undeserved lead from a dodgy-looking penalty, Mario Carevic converting from 12 yards. Cue the lighting of a dozen or so flares. Five minutes before half-time, the stadium still engulfed in smoke and the choking smell of sulphur, Eduardo waltzes past four Hajduk defenders and is up-ended in the box: another penalty, another goal.

Eduardo celebrates by kissing his Dinamo badge and running directly towards the Hajduk fans, who respond with more monkey chants and a hail of mobile phones.

In the second half, another 20-man brawl ends in Carevic’s dismissal and the visitors capitalise when Davor Vugrinec stabs home from five yards after a well-worked move: 2-1 to Dinamo.

Up in the VIP area, Dinamo staff are on the receiving end of torrents of abuse, including one skinhead accusing the club president of paying the referee, but with eight minutes to go, it’s the Hajduk fans who are indebted to the official Drazenko Kovacic when he awards their side a second dubious penalty.

The Poljud Stadium is said to be earthquake-proof and it needs to be when Pablo Munoz converts the penalty. The whole place trembles and the fireman whose job it is to put the burning flares into buckets of water is soon working overtime.

A bus carrying Dinamo fans is pelted with bricks and stones, smashing all its windows; this is “nothing special” for derby day

As the final whistle blows and fans stream out into the streets, FourFourTwo reflects on a classic derby, low on quality but with four goals, three penalties and one red card, played in an electric atmosphere. In the next day’s newspapers, the game enjoys front and back page coverage.

Almost as prominent as the scoreline is the arrest count – ‘Torcida 30, Bad Blue Boys 9’ reads one headline. The only major off-field incident occurs when a bus carrying Dinamo fans is pelted with bricks and stones, smashing all its windows, but according to Torcida member Ivan Pupacic, this is “nothing special” for derby day.

On the field, the result means the sides stay level on points at the top of the Croatian championship. Going into the winter break, the title race is, again, between the country’s big two. There will be a lot at stake when the sides meet in Zagreb on February 24. Bogdan Urukalo, for one, has the date ringed in red in his diary.

“We wait the whole year for this match,” he says, excitedly, like a child talking about Christmas. “I’m already thinking about what we will do for the next derby, it’s in my head all the time, I can’t wait.”

This feature originally appeared in the March 2007 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe!

World's Biggest Derbies • More Than a Game