Bullfighter, stamper… legend: why Juanito is an all-time Real Madrid hero

No Madrid player is more beloved by die-hard Blancos than the irascible wideman, who died in a car crash at 37 – though Lothar Matthaus wasn’t a fan...

There are tears in Juanito’s eyes. “I’m cursed,” cries Real Madrid’s right-winger to the Spanish press corps at full-time of Real Madrid’s 4-1 defeat at Bayern Munich in the first leg of their 1986/87 European Cup semi-final. “I thought that I'd changed as a person and as a footballer, but clearly I haven’t.”

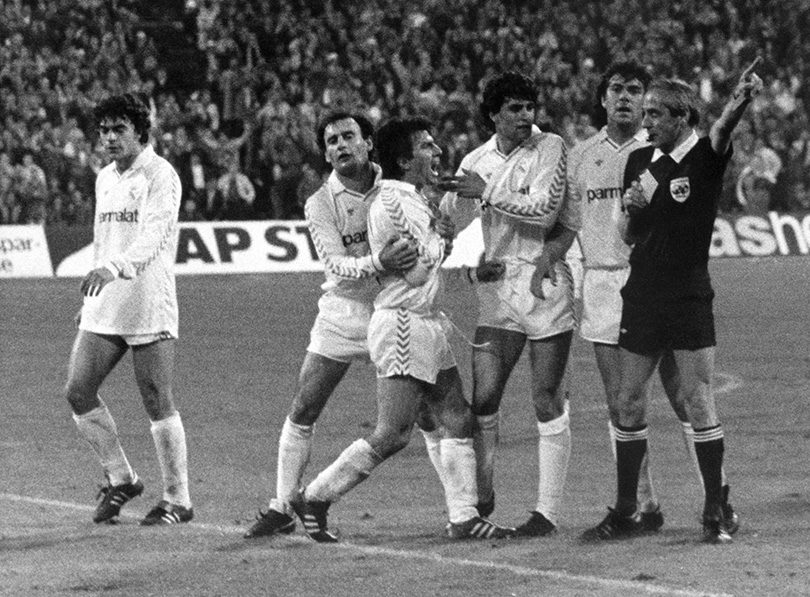

The emotional 32-year-old from Andalucia, with his all-encompassing will to win, has been sent off on a chilly April evening in Germany for stamping on Lothar Matthaus’s head.

“Things like this could result in my retirement from this sport,” he adds. “In those moments, you’re not yourself. There’s another person controlling you; you do things you don’t realise. Seriously – I didn’t know what I was doing.”

The video replays, shocking in their brutality, go around the world. UEFA decide to ban Juanito from playing in European competitions for five years. Real Madrid’s disciplinarian manager, Leo Beenhakker, can no longer tolerate this loose cannon with an extensive rap sheet of carnage that also includes spitting, punching a referee and even clandestine bullfighting. His summer sale to second-tier Malaga will soon be confirmed, ending a decade-long spell at the Santiago Bernabeu.

Los Blancos’ fans are distraught by his departure, however. Perhaps more than any other player, the winger had come to define madridismo – the very essence of what it means to wear the famous white jersey of Real Madrid. “If I wasn't a player,” Juanito once said, “I’d be an ultra sur.” One of them, essentially.

He was Madrid's version of John Terry: almost universally hated outside of his club but a winner who’d do anything for the cause. He’s a winner still present at every Madrid game, despite his tragic death in April 1992 at the age of 37.

“He was the opera singer; we were just the accompaniment”

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Juan Gomez Gonzalez grew up kicking a football with dad Juan Sr around the beaches of Fuengirola, a fishing village on the Costa del Sol increasingly loved by lobster-tanned, sun-seeking Brits in the 1950s.

Juanito’s route to Real Madrid would inform the rest of his playing career to follow: a triumph of hard work and never-say-die spirit. After three years in Atletico Madrid’s youth team, a serious knee injury forced the 17-year-old into semi-obscurity at Burgos, where he excelled. In his second season there, 1975/76, he almost single-handedly won the club promotion to the top flight – and then kept them there the next year. Prestigious magazine Don Balon named him player of the season.

“He was a crack,” team-mate Pepe Navarro recalled. “He was explosive. He’d drop his shoulder and be off. He was the opera singer, and we were just the accompaniment.”

Spain’s giants soon came calling, and Real Madrid beat arch-rivals Barcelona to the most coveted signature in the country. Juanito wasn’t the quickest, the most skilful or the most prolific goalscorer, even if he did win the Pichichi trophy in 1983/84 as the league’s top marksman. He was, however, the team’s correcaminos: the roadrunner who would never tire and never acquiesce to defeat.

“Juanito’s arrival was so important for Real Madrid,” said Carlos Santillana, the centre-forward and main beneficiary of Juanito’s right-wing supply line. “He had spark, and genius in doing what was needed. He was a winner and he’d sweat through his shirt for 90 minutes.”

He took his work home, too. The winger’s daughter, Jenifer, recalled: “Whenever Madrid lost, there were two days of silence. You couldn’t talk about football, and only about sport in general if it was in a very low voice. He hated losing, even if it was at cards.”

Juanito won three consecutive league titles with Real Madrid and reached the 1981 European Cup Final in Paris, where they lost 1-0 to Liverpool. And he was the team’s light relief, claiming that defeat was all the fault of his great friend, Santillana, for allowing his wife to wear unlucky yellow to the final. He was only half-joking: once, at a casino in the early ’80s, Juanito laughed at a team-mate for putting their chips on 13. When it came in, he kicked over the roulette table and stormed out.

Further success on the pitch was headlined by back-to-back UEFA Cup wins in 1985 and ’86, despite losing his regular spot in the starting XI during the mid-1980s to a group of youth-teamers led by striker Emilio Butragueno that was nicknamed La Quinta del Buitre – the Vulture’s Squadron. Juanito even acted as mentor and room-mate to Michel, his direct replacement.

- WHERE ARE THEY NOW? Real Madrid's homegrown '80s greats La Quinta del Buitre

It was his personality that Los Blancos prized most. The consecutive UEFA Cup triumphs were underpinned by some stunning second-leg comebacks to see off Anderlecht (6-1), Inter (3-0), Borussia Monchengladbach (4-0) and Inter again (5-1). He became the inspiration for the remontada, or fightback, that characterised this era of success for the Madridistas. “Every game, the same thing would happen,” recalled Michel. “We’d lose the first game away, then win at home. We would be in the dressing room and Juanito would come in and say, ‘How can you let that happen?’ You wouldn’t think that such a short and stocky bloke could inspire people in the way he did.”

Real Madrid’s comeback at home to Monchengladbach in December 1985 stands out. When Santillana scored two minutes from time to make the score 4-0, Juanito – the indisputable hero, about whom newspaper ABC said the following day, “It’s not possible to play better” – couldn’t contain himself. “He started screaming as if he were an ultra,” recalled Jorge Valdano, forward and future sporting director of Real Madrid. “He was so happy, jumping up and down, punching the air. He really connected with the Bernabeu.”

Yet it was that ferocious will to win which got Juanito into trouble. After Grasshopper Zurich knocked Madrid out of the 1978/79 European Cup, he punched referee Adolf Prokop, who had allowed a contentious late offside goal to stand. The result was a two-year suspension, later halved on appeal.

Then, during the 1985/86 UEFA Cup quarter-final against another Swiss club, Neuchatel Xamax, he spat at opponent and former Real Madrid colleague Uli Stielike. “I knew what to expect,” recalled Stielike, who hated Juanito’s emotional mannerisms, especially during the latter’s divorce two years previously. “We were team-mates in the dressing room but we never went for a beer together, let alone socialise.”

Juanito even took on the Real Madrid power brokers, participating in a charity bullfight without permission.

The final straw

“You couldn’t tell Juanito not to do something, because he wouldn’t listen,” former Real Madrid left-back Antonio Camacho later said. “He brought the video of the fight onto the bus to an away game, where the coach, sporting director and more were sat. It was as if he was saying, ‘I’m putting this video on and I want you to fine me’.”

The fine duly came. Juanito’s card had been marked. So when his studs got up close and personal with Lothar Matthaus’s cheek, a furious Beenhakker had seen more than enough. “At that level you need a clear head,” said the Dutchman. “Matthaus is far from the nicest person, but as a professional you have to control yourself.”

Juanito hung up his boots at Malaga two years later in 1989, having won the Segunda title the previous season, and threw himself into management with second-tier Merida in 1991.

He died on April 2, 1992, aged 37. Travelling home from Real Madrid’s UEFA Cup tie with Torino, he was asleep in the passenger seat when the driver – Merida’s fitness coach – crashed into a stationary lorry after swerving to try to avoid a truckload of spilled logs on the carriageway. Juanito never woke up – he was killed on impact.

WHERE ARE THEY NOW? Real Madrid's 1998 Champions League winners

Spanish football went into mourning, even in Barcelona. “He was a player who defined an era,” said Barça manager Johan Cruyff. Former Real Madrid full-back Rafael Gordillo still carries Juanito’s picture in a necklace locket.

During the seventh minute of every Bernabeu game, the ultra sur rise to pay homage to their fallen idol and most loved No.7 (even ahead of Raul). “Illa,illa,illa, Juanito maravilla,” they sing. “Hey, hey, hey, Juanito the wonder.”

“It’s a throwback to the authentic Madrid of times gone by,” Valdano concluded. “It gives you goosebumps.”

That memory will last longer than five seconds of madness on a chilly April evening in Bavaria. A wonder, indeed.

This feature originally appeared in the February 2017 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe!

Andrew Murray is a freelance journalist, who regularly contributes to both the FourFourTwo magazine and website. Formerly a senior staff writer at FFT and a fluent Spanish speaker, he has interviewed major names such as Virgil van Dijk, Mohamed Salah, Sergio Aguero and Xavi. He was also named PPA New Consumer Journalist of the Year 2015.