Champions League group stage draw: Who are the most likely opponents for Liverpool, Manchester City, Manchester United and Chelsea?

The Champions League group stage draw takes place this evening – and thanks to the power of maths, we already have some idea of who will face who

Just over a month after last season’s final, the Champions League is already back. The European football season really kicks off today with the draw of the Champions League group stage, which will spread over only a month and a half, from the end of October to early December.

The eight groups of four teams each will be drawn from four pots of eight teams; each group is made of one team randomly drawn from each pot.

Since 2015, UEFA seeds the domestic champions of the highest-ranked leagues in pot 1 together with the title holder. In 2018, the Europa League title holder also gained direct access to pot 1.

The following pots are built following the UEFA club coefficient, with the 'best' teams in pot 2 and the 'weakest' teams in pot 4.

All English teams are in pots 1 and 2. Premier League champions Liverpool are in pot 1, while Manchester City, Manchester United and Chelsea have been seeded in pot 2.

How the calculations work: the obvious bit

The groups will not be formed completely at random. One well-known UEFA rule is that two teams from the same country cannot be drawn into the same group. This greatly impacts the draw probabilities.

For instance, Liverpool can only be drawn against five teams from pot 2: Barcelona, Atletico Madrid, Shakhtar Donetsk, Borussia Dortmund and Ajax. As a consequence, Ajax, even though it can play against all pot 1 teams, will have an almost 20% chance of facing Liverpool – but only around an 8% chance of facing Juventus, Paris Saint-Germain or Porto.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

One could think that Liverpool has exactly a probability 20% of being drawn against each of its five possible pot 2 opponents. This would indeed be the case if the draw started with randomly picking one of those five teams. However this is not how the draw works.

Let us focus for instance on the likelihood of Liverpool-Ajax. Of course, it cannot be at the same time 20% (from Liverpool having only five possible pot 2 opponents) and 12.5% (from Ajax having eight possible pot 1 opponents). One could list all the admissible outcomes for pots 1 and 2, and estimate the likelihood of Ajax-Liverpool by the proportion of admissible outcomes where the Reds face the Dutch. However, this would not yield the correct probabilities either, because this is not how the draw works either.

In fact, pot 1 teams are first placed randomly in groups A to H. Then pot 2 is emptied, and each time a team is drawn from pot 2 a computer lists the admissible groups for that team. (This is not as simple as it looks, as it requires checking for possible dead-ends.) One such group is then randomly drawn. For instance, if Ajax is drawn first from pot 2, it will have a 12.5% chance of facing each pot 1 team. However, if Ajax is drawn after City, United and Chelsea, Ajax will have much fewer options, but Liverpool’s group will likely still be available for them since English teams will not have ended there. This naturally increases the chances that the Dutch face Jürgen Klopp’s players.

How the calculations work: the less obvious bit

Another less known rule complicates the computation even more. UEFA uses TV pairings so as to maximize TV viewing. Paired teams from the same country, say Real Madrid and Barcelona, are allocated to two different halves of the groups (groups ABCD vs groups EFGH), so that if one team plays on the Tuesday, the other team plays on the Wednesday.

This year the TV pairings have not been made public yet, but for England we have assumed that Liverpool is paired with Manchester United, like two years ago, and that City is paired with Chelsea. In particular, this means that during the draw, if Liverpool is placed in groups ABCD, United fans can presume that the Red Devils can only be drawn in groups EFGH.

TV pairings make the probability calculations even more complex. They have a complicated impact on the draw probabilities, which is often underestimated.

Crunching the numbers

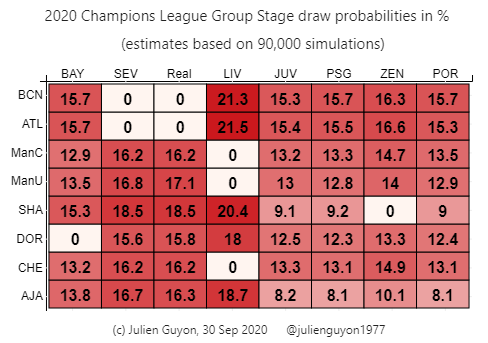

In order to estimate the correct draw probabilities, I have simulated 90,000 draws following exactly the UEFA procedure. The most likely matchups are Liverpool vs Barcelona or Atletico (around 21.5% each); the least likely ones are Ajax vs Juventus, PSG or Porto (just north of 8% each).

The most likely opponents of Manchester United are Real Madrid and Sevilla (around 17% each); the Red Devils only have about a 13% chance of facing Juventus, PSG or Porto.

Manchester City and Chelsea have similar draw probabilities, but are a little less likely to be drawn against Real Madrid or Sevilla than Manchester United.

The small fluctuations that you observe in the probability table are only due to the so-called sampling error – the fact that we only simulate a finite number of draws. In particular, as regards draw probabilities, Chelsea and Manchester City are perfectly interchangeable, so they share the exact same probabilities. The same is true of Sevilla and Real Madrid; Barcelona and Atletico; and Juventus, PSG and Porto.

United are not interchangeable with Chelsea and City because of the TV pairings – this is why Real Madrid is a slightly more likely opponent (and Zenit a slightly less likely opponent) for the Red Devils, for instance.

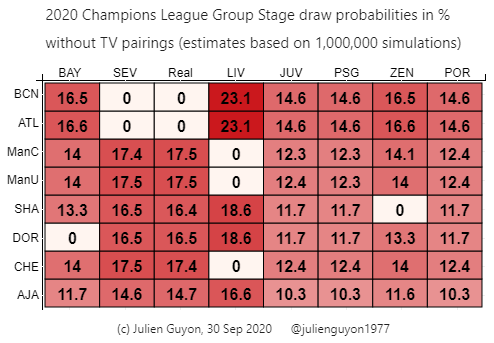

In order to measure the impact of TV pairings on the draw probabilities, I have also performed simulations that ignore them. TV pairings have a sizable impact. While they decrease Liverpool’s probability of meeting Barcelona or Atletico by about 1.5 point, they increase the probability of a Liverpool-Ajax matchup by about 2 points.

A final fact is that while Dortmund is Liverpool’s least likely opponent, Liverpool is actually Dortmund’s most likely opponent. And there is nothing illogical with this. Ah, the beauty of mathematics.

Julien Guyon is a French mathematician and football fan. He is a quantitative analyst, and adjunct professor in the Department of Mathematics at Columbia University and at the Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, New York University. He has written on mathematics and football for The New York Times, The Times and Le Monde. More probability tables are available on the author’s Twitter account and on his website.

While you’re here, why not subscribe to the mag - and get your first five issues for just £5!

NOW READ...

GUIDE Premier League live stream best VPN: how to watch every game from anywhere in the world