Chelsea and Arsenal face up to lack of striking options

As Chelsea face Arsenal, Michael Cox examines both sides' relative lack of striking options - also found this in this week's FFT Weekly...

As footballing identities go, Chelsea and Arsenal have little in common. In fact, they’re polar opposites – and that schism, combined with both sides’ regular top-four finishes over the past decade, means this rivalry is particularly fierce.

The two clubs simply go about their business in entirely different ways. Chelsea have consistently spent huge sums of money on new recruits, and often played quite defensive, mechanical football – but have won a succession of trophies in recent years. Arsenal, in contrast, have been reluctant to spend money and have taken pride in their open, attacking football, but their trophy drought is the obvious flaw.

There’s not much in the centre of the Venn diagram, but recently the two clubs have, strategically, encountered the same dilemma – both have found themselves without a regular goalscoring striker, but a plethora of talented onrushing midfielders. For the first time, Jose Mourinho and Arsene Wenger are in the same situation. How do they get their side scoring goals without a Didier Drogba, or a Robin van Persie?

Three or one?

Starts+subs (goals)

Torres

Lge 13+8 (4)

Cups 5+4 (5)

Total 18+12 (9)

Eto'o

Lge 14+4 (7)

Cups 9+3 (3)

Total 23+7 (10)

Ba

Lge 2+12 (3)

Cups 1+6 (2)

Total 3+18 (5)

Giroud

Lge 27+0 (12)

Cups 9+4 (6)

Total 36+4 (18)

The striking situation is similar, but different in nature. Mourinho’s problem is that he has three genuine options up front – Fernando Torres, Demba Ba and Samuel Eto’o. At their peak, all three were prolific: Torres was the most feared striker in England, Ba made a sensational impact at Newcastle, and Eto’o was arguably the best in Europe.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

All three have declined, however, and Mourinho is rather caught between two different objectives – should he concentrate on maximising the individual goalscoring ability of his main striker, or focus on them playing a selfless role and bringing others into play?

Wenger, on the other hand, only has one genuine centre-forward option in Olivier Giroud. He’s started 28 of 30 games as Arsenal’s lone striker – although it’s worth pointing out that on the other two occasions, much-maligned back-up Nicklas Bendtner has opened the scoring on both occasions. Still, Giroud is the main man.

That familiarity has helped Arsenal this season, because Giroud has a good relationship with Arsenal’s various attacking midfielders. As outlined recently, when comparing Giroud to Emmanuel Adebayor and Spurs’ inability to get midfield runners ahead of the Togo striker, Arsenal understand precisely what Giroud wants to do. He wants short passes played into feet, and he wants the likes of Jack Wilshere, Tomas Rosicky and Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain to storm past him into space.

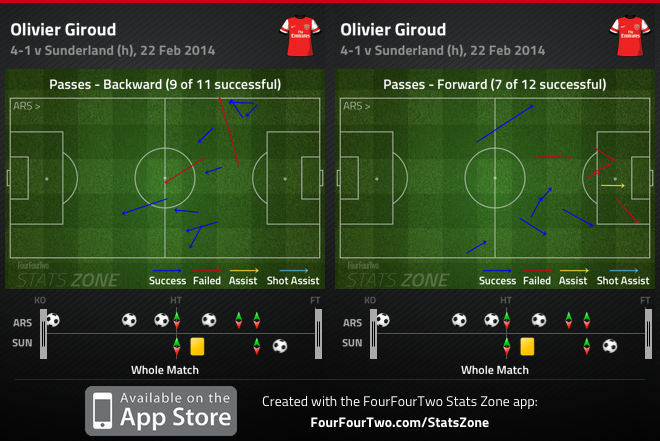

Giroud was involved in Wilshere’s excellent goal against Norwich and Rosicky’s similar strike against Sunderland – both 4-1 wins – contributing a clever flick in each.

He also looks for a quick, killer pass when receiving possession, often an ‘around the corner’ ball. This means his forward passes regularly go astray – but he often provides an assist.

Giroud’s as much a provider as a goalscorer – he’s the Premier League’s joint-seventh top scorer, and the joint-seventh top creator. However, question marks remain about whether he produces against the best sides in the division. He missed a golden chance early on against Chelsea last season at Stamford Bridge, a 2-1 defeat – and since his arrival in English football he’s only scored once against any of the Premier League’s top seven, a winner against Spurs in September.

The Spanish Heskey

Chelsea’s situation is different. Eto’o and Torres are naturally better players than Giroud, but don’t have the searing pace of their younger years. Instinctively, Eto’o and Torres like to sprint in behind the opposition defence, and have been forced to adapt, playing a hold-up role when possible to facilitate the likes of Eden Hazard, Andre Schurrle and Willian.

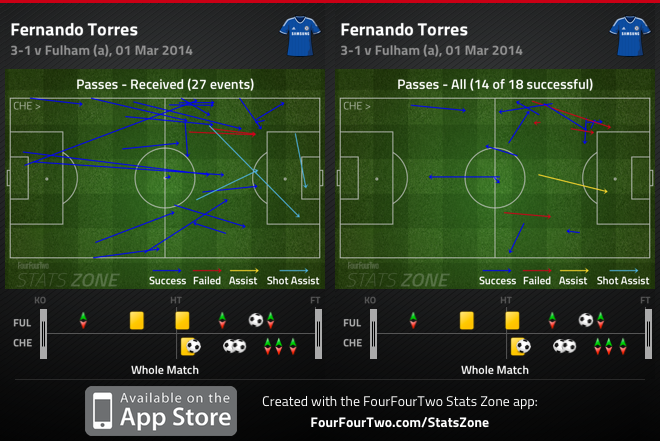

Torres is probably marginally better at playing a hold-up role – almost as if he’s had more time to accept his reduced capability. Even leading up to World Cup 2010, before Torres’s decline had really been recognised, Sid Lowe described him as “Spain’s Emile Heskey”. To a certain extent, that’s what he’s become at Chelsea, too. Against Fulham, for example, he held up play nicely and provided a great through-ball for Schurrle:

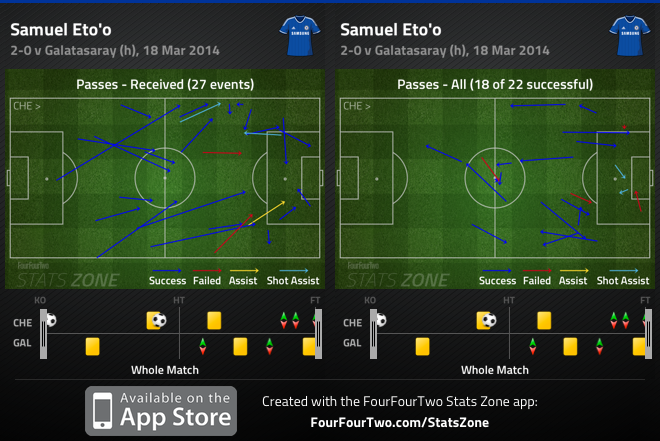

Eto’o, however, has emerged as a more regular scorer in big games. He has netted in his last two games – the openers against Galatasaray and Spurs – and also got the winner at Christmas over Liverpool and a hat-trick against Manchester United in January; the problem is the run of seven goalless starts between the United and Spurs games. His hold-up play is neater, and more precise, but probably not as incisive.

Overall, you’d probably rather be in Wenger’s position – at least as far as the centre-forward is concerned. Giroud is much less likely to score a hat-trick than Torres or Eto’o, but probably understands his role in his side much better. Ultimately, however, Saturday afternoon’s game will be decided by the performances of the attacking midfielders – the men these strikers are teeing up.