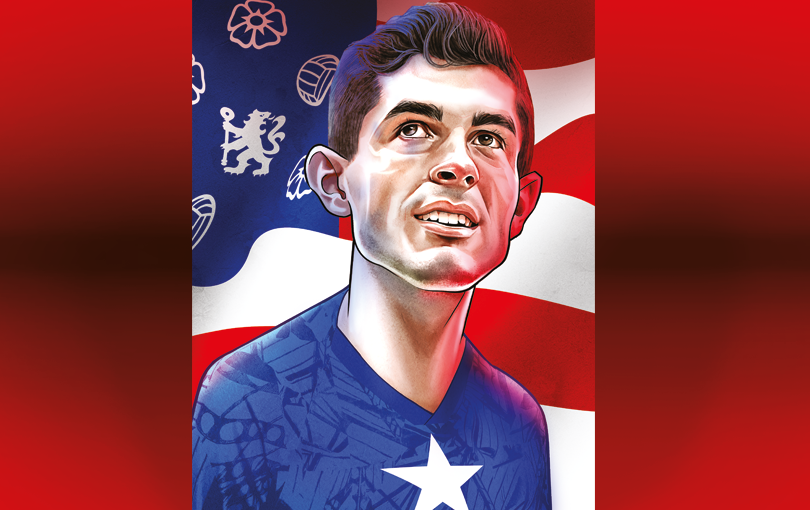

Captain America: Can Christian Pulisic really fill the hole left by Eden Hazard for Chelsea?

The Blues' £58 million signing announced himself in the Premier League with a hat-trick against Burnley, but has already made waves for Borussia Dortmund and the US national side. Can Frank Lampard unleash the 21-year-old's potential?

This feature first appeared in the September 2019 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Buy it here!

Christian Pulisic’s life has moved fast. He’s only 21 years old, but already Chelsea’s £58 million signing from Borussia Dortmund – the most expensive American footballer of all time – is a record-breaker hailed as the man who will be America’s first global soccer superstar. He’s the youngest player to score for and captain his country; the youngest foreigner to score in the Bundesliga and play Champions League football for Dortmund. He talks about these milestones in the way other teenagers discuss classes they’ve attended.

This attitude has helped Pulisic to get where he is today. He wasn’t fazed by playing with the bigger boys as a kid, nor by moving around so frequently that he “didn’t really do high school”, nor by working under six managers in five years in front of football’s highest average crowds of 81,000. Significant setbacks for this level-headed youngster are seen as “tough”, “disappointing” or something to learn from.

At Dortmund, Pulisic was one of very few fully established teenagers at a major club. He’d played 60 first-team games by the time he turned 19. At the same age, Lionel Messi had made only 34 Barcelona appearances; Cristiano Ronaldo, a combined 53 for Sporting and Manchester United.

Pulisic took everything in his stride – until he met Messi. In 2016 the pair were chosen at random to do a doping test in the bowels of Houston’s vast NRG Stadium, following the Copa America Centenario semi-final between the USA and Argentina. Messi is a fellow diminutive dribbling attacker with a low centre of gravity, who played on the wing in his teens and who loves to run at defenders – who, in turn, love to foul him. Eventually Pulisic wants to play centrally as a No.10.

PULISIC PUNISHES!

Frank Lampard has been questioned over Pulisic's lack of minutes so far, but the American has shown what he's about here!

Watch on Sky Sports Premier League

Follow #BURCHE here: https://t.co/4uRam6qqjS

Download the @SkySports app! pic.twitter.com/6IlFLjszxu— Sky Sports Premier League (@SkySportsPL) October 26, 2019

“I had to get my phone to have a picture taken with him,” Pulisic admits in an exclusive interview with FourFourTwo, which takes place in his Chicago hotel before USA’s Gold Cup final against Mexico in July. “We couldn’t really communicate, but he was really nice about the whole thing. He probably gets it a lot.”

Messi, like many of the world’s greatest ever footballers, is a barrio kid; a street footballer from a working-class background. Pulisic is different: a slice of the American dream, but with the success that has eluded even their finest soccer players.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

The world’s richest country has yet to produce a truly world-class footballer, with Landon Donovan the most lauded so far, but Pulisic is looking like he could be that man. Earlier this year he was runner-up to Kylian Mbappe in the inaugural Kopa trophy for under-21s. It was awarded during the Ballon d’Or ceremony and voted for by the previous 33 Ballon d’Or winners. Justin Kluivert came third. Trent Alexander-Arnold was sixth.

Pulisic’s story reads like a childhood fantasy. “I lived next to a theme park by the chocolate factory,” he says in measured, softly-spoken tones. “I’d be there every day in the summer. I’d measure myself against the Hershey candy characters which were used to see if you were tall enough to get on the rides. I always wanted to be as tall as the Twizzlers character, because then you could go on every ride.” It was wishful thinking – he was tiny.

“Hershey was an awesome place to grow up – a small town where everyone knew each other,” he continues. “It wasn’t a soccer town, so I was an outcast just because I played soccer and both of my parents loved soccer.”

His dad, Mark, was a prolific goalscorer who played professionally with Harrisburg Heat in the indoor league. His mum, Kelley, played soccer in college, too.

But in Hershey (population 14,800), Pennsylvania, Americana, there was no one to play with.

“My friends would play American football or baseball or basketball,” recalls Pulisic. “When they’d finished, I’d go home and play soccer with my mum and dad, using the garage as a goal. No one played soccer in my neighbourhood. My friends thought it was strange but I didn’t care. I played other sports, too. I was a good basketball player.”

Mark Pulisic, who has long called his son ‘Figo’ after the great Portuguese winger they both loved to watch, painted the word ‘CONFIDENCE’ in yellow paint on the wall of the garage.

“Dad wanted to instil that in me from a very young age,” explains his son. “It was a key word to me. I needed it, because I was always playing against older boys. I needed to be confident. I honestly didn’t fear anyone, and playing against older, more physical boys helped me. I had to think faster; I had to be more technical. That definitely helped me.”

The more surprising aspect of Pulisic playing above his age level was his size. At football tournaments, parents would ask his mother if he was someone’s little brother.

“I was the smallest even when I played in my own age group,” he explains. “I was a later bloomer, definitely. I started growing more at 15 and 16, but being small wasn’t a disadvantage. Physically I wasn’t as capable as some of the other boys, but you can be a great player at all sizes. I just had to think smarter and quicker. Being smart at that age would ultimately be an advantage.”

Pulisic, who turned 21 in September, is now sponsored by his hometown chocolate company and has stayed in touch with his schoolfriends – although, such was his rise at a young age, his life was unconventional.

“The night before I scored my first goal for the national team [USA vs Bolivia in Kansas], I went to my school prom,” he says, laughing. “I missed out on so much as a kid playing football that I didn’t really go to high school. I’d been in England as a younger kid, I’d been in Florida, and I moved to Germany when I was 15. And I thought a lot about what I had missed out on. I spoke to my coach, Jurgen Klinsmann, and asked him if I could go to the prom. He was so nice about it and told me to go. I made it back in time for the game the next day.” Being able to hire a private jet for a round trip from Kansas to Hershey was also a sign of his increasing wealth.

Klinsmann later hailed Pulisic and his “absolutely unlimited potential”. As for England, Kelley received a Fulbright scholarship for a teaching exchange. The family moved to Brackley, near Oxford, when he was seven.

“I didn’t want to leave America and my friends,” he says of the move made when he was seven. “Going to England was a big shock for me. But, in the end, it was the best thing that happened. I could play soccer every day after school, something I’d dreamed of doing at home. I’d play on a cement football pitch by school, then go for training with Brackley Town. I loved that. I felt the whole country was obsessed by soccer – something I’d never experienced. My Brackley coach, Robin Walker, came to see me play in Dortmund.

“I also went to see English football games for the first time. Dad took me to Old Trafford first. There’s a picture of me at Old Trafford on Dad’s shoulders. I was amazed by the whole experience, and the technical levels of the players, being watched by so many people. It’s crazy that my first game in England [was] at Old Trafford for Chelsea.”

The Pulisic family moved back to the States after a year, his dad coaching an indoor team in Detroit and Christian learning ball tricks from their Brazilian players. His influences were growing. “My friends told me that I had a British accent, which made me so mad,” he reveals. “I yelled ‘Mum!’ and my sister said, ‘You said ‘mum’! You’re British’.”

The peripatetic existence continued even back home in America, where Pulisic joined Pennsylvania Classics youth club.

“Then, after my first year of high school, I won a place to the IMG Academy for the US Soccer Residency programme in Florida,” he explains. “We would train every morning and go to school in the afternoon. Florida was hot all year round, which was new to me, and I loved it. I was training with the country’s best players in my age group, and I felt that it took me to another level.” And academically?

“I was actually very good. I got good grades. My problem was that I had been away so much with soccer in my first year of high school that I was always playing catch-up.”

In 2013, aged 15, Pulisic played for the USA in a series of Nike-organised friendlies. He was named player of the tournament.

“They changed my life,” he tells FFT. “For the first time, I felt that I could make a living professionally. I was playing against some of the best players in the world for my age from the national teams of Portugal, England and Brazil, who we beat 4-1.”

He scored 20 goals in 34 games for the USA Under-17s. Interest was forthcoming from Europe and especially Dortmund, though he had long been on the radar of clubs – and had already worn a Chelsea shirt.

“It’s really strange – I actually trained with Chelsea when I was a child,” he explains. “I went to London and spent a few weeks with their youth academy.”

He also trained with Barcelona at the age of 10 after impressing in the MIC Cup, one of the elite youth tournaments, which is held annually in Catalonia. “I had a great game against Barcelona and I was informally invited to train with them,” he says. “It was another great experience.”

Pulisic’s family felt that, rather than stay in the US, he would develop better across the Atlantic amid superior standards. “My parents were very cautious about the timing,” he says. “They didn’t want me to go to play in Europe too early and for it all to be too much for me.”

There was an offer of an MLS contract but he was wanted by Dortmund, with their track record of developing youth and playing young players in the first team. There was an issue, however: European clubs aren’t allowed to sign non-European passport-holders until they’re 18. Pulisic was 15 and didn’t have a European passport, which meant that he couldn’t play games for his first six months in Germany while he waited for his Croatian passport to be issued.

“That was heartbreaking,” reveals Pulisic, “but my grandpa was Croatian so we were allowed a passport. Playing in Europe at 16 gave me a real advantage because it allowed me to play for Dortmund’s youth team. More than that, it allowed me to make my debut in the Bundesliga before I was 18. If I hadn’t had a European passport then I would have still been in the US, rather than playing in one of the top leagues in the world. At 17, I was training with the pros, and that made a huge difference to my game.”

While his football went well, moving to a new country where he didn’t speak the language was difficult for Pulisic.

“My dad lived with me for the first couple of years until I was 18,” he says. “Dad wasn’t much of a chef, so we would have a lot of takeaway chicken from the same place a few blocks from our apartment. But the food was fine. The hardest bit was school.

“It was the hardest couple of years of my life. I thought about home a lot. I didn’t speak a word of German but I was put into a German school with a full schedule. Because I couldn’t understand the schedule, I didn’t know where I was supposed to be. I hoped the teacher would know I couldn’t speak the language, but I had a situation where the teacher asked me something in German. I didn’t know what she was asking me, so I replied, “I’m sorry, I don’t understand” in English. She looked at me as if to say, ‘What is going on?’ Some of the other kids explained to her that I didn’t speak German. I hoped the teachers would know that I was a new student from America, there to play football, but this teacher didn’t.

“It was strange. There was no way that I could learn fluent German in a few weeks, so I had to change some classes around. I was fine in English and art, but in other classes I’d nod my head most of the time.”

And language wasn’t the only barrier. “On top of school,” recounts Pulisic, “I had one German class each day and I also had to go to the gym and to training. It was very tiring – I’d go straight home to sleep. I had to look at the bigger picture, though, and persevere. I’m happy I went through it all. And I can speak German, so it was worth it.”

On the pitch, Pulisic felt that, initially, other players were looking at him and thinking, ‘Who is this American, coming to take our place?’ But he got into the under-17 team that won the Bundesliga title in his first season.

“We had a very good team and the coach, Hannes Wolf, was a mentor. I got to train with the pros, too. Jurgen Klopp called me up to be with them. I looked around and saw players like [Pierre-Emerick] Aubameyang, Mats Hummels, [Henrikh] Mkhitaryan, Marco Reus – people I’d seen on TV. It seemed crazy, yet they were so humble in training. You follow their behaviour. Klopp would always smile. He was friendly when he didn’t need to be. I’m thankful that he gave me the chance. That made me feel I was on the right path.”

Klopp moved to Liverpool, to be replaced in Dortmund’s football factory by Thomas Tuchel.

“He invited me to Dubai for a mid-season training camp,” says Pulisic. “He also asked me how I’d feel about playing for the first team full-time. I was in shock, partly because that would mean stopping school completely! The idea of training and then having the rest of the day to myself was a dream.”

Tuchel saw the potential – the speed, sharpness, strength, sublime fitness and mature decision-making that belied his age and led Jens Lehmann to say, “He makes difficult things look easy, so he’s a boy to watch.” Tuchel himself was just as glowing in his praise, calling Pulisic “the kind of guy who’s very self-confident, shows his talent on the pitch, and doesn’t show any nerves under pressure – which is a wonderful combination”.

But the pair didn’t always see eye-to-eye. The current PSG coach wanted Pulisic at wing-back. The American had never played there.

“I was frustrated,” he remembers. “But this is something that every young player has to go through. From his perspective, he had such a talented team and he was looking at the areas where he felt I could help the team. That’s what a coach should do. Even if it wasn’t what I wanted, I’m thankful that he put me in such a strong team. He put me on when were 3-1 down to [rock-bottom] Ingolstadt.”

Pulisic set one up and scored the equaliser. “My dad was there – it was unforgettable,” he says. He was 17 years old.

Nuri Sahin, formerly of Liverpool and Real Madrid, took Pulisic under his wing.

“He’s fearless,” said Sahin. “He has so much speed, but what I like most is his first touch. When he gets the ball, his first touch opens up a huge space for him even if there’s no space.”

Pulisic shared very few of the first-team players’ trappings. He was too young to drive, so his father, Mark, gave him a lift to training each morning in a modest VW Golf. Then Mark went back to America to coach, while Christian lived with his cousin, Will, a goalkeeper also playing in the younger teams at Dortmund.

“I’d watch Netflix series,” was how he enjoyed his new-found spare time. “I’m into gaming with my friends from back home, too. That’s how we keep in touch.”

His close friend, Nicholas Taitague, is American, the same age and playing in Germany for Dortmund’s rivals, Schalke. Taitague and Pulisic played Fortnite on their PlayStations most days.

“I watch other sports, especially NBA,” says Pulisic. “I like the Sixers [Philadelphia 76ers] but I’m a big LeBron James fan, too. I follow players more than teams.” In fact, Pulisic put a quote from LeBron, whom he often stays up late to watch, on the door of his Dortmund apartment, which read simply: ‘Outwork your team-mates every day’.

Except, apparently, in the kitchen. “I wouldn’t exactly say I was a natural at home-keeping,” he laughs. “I had the three meals I knew how to make on rotation.”

By 18, Pulisic was living the life of a professional footballer – usually for the better, but sometimes for the worse. On April 11, 2017, he was sitting next to goalkeeper Roman Burki on the team bus for the home leg of Borussia Dortmund’s Champions League quarter-final against Monaco as the bus closed in on the stadium.

“We had a normal schedule and I had my headphones on as we drove to the game, as I do for every game,” he remembers, solemnly. “What happened next seemed to happen in slow motion. First, windows on the bus shattered, then everything started to shake. I had no idea what was happening – I was just very confused. Roman grabbed me and pushed me to the floor under the table on the bus. The noise stopped, but then we heard Marc yelling.”

Catalan defender Marc Bartra was taken to hospital with a broken wrist, while a police motorcyclist escorting the bus suffered blast injuries and shock from a bomb, detonated by a 28-year-old German-Russian who’d learned how to make it on Google. He wanted to profit from Dortmund’s share value dropping. The damage would have been much worse if the bus windows hadn’t been reinforced.

There were three explosions.

“We didn’t know what was happening, or what was going to happen,” says Pulisic. “We had been preparing for a game and I wondered if we would still play. Eventually, we were told that we’d play the next day.”

Dortmund wanted the match rescheduled for a later date, but – to much criticism – UEFA refused their request. Monaco won 3-2 in Dortmund and progressed to the semi-finals.

“It was a tough time,” recalls Pulisic, just 18 when the attack took place. “I was nervous in the months after. We didn’t stay at the same hotel for a few months, but we still needed to get the bus to games and we still had to pass the place where it happened. It was especially tough when we got on the team bus and sat in the same seats. It will always be part of me. It brought me close to my team-mates.”

Tuchel left the club six weeks after the attack to take a year out of management. He was replaced by Dutchman Peter Bosz, who had just taken Ajax to the 2017 Europa League Final, where they lost to Manchester United.

“He had a lot of trust in me and allowed me to play a very free and attacking style,” says Pulisic. “I really respected him as a coach and it was tough when he was fired [four months into the season, with Dortmund 8th in the Bundesliga and winless in all six Champions League games]. Things had gone really well in the league, then we missed out on a few results. I’m only young but I’ve had several coaches, and you have to start over again – changing tactics, playing to a new system.”

Pulisic was now playing under Austrian Peter Stoger, Dortmund’s boss for six months, and by 2018 speculation was increasing that the winger would be leaving the club, either for England or Bayern Munich. Klopp had always followed his career, Manchester United were fully aware of him, but – despite the apparent turmoil at Stamford Bridge – it was Chelsea who were consistently keenest on signing Pulisic. Dortmund, who had lost Ousmane Dembele to Barcelona in the summer of 2017 and Aubameyang to Arsenal six months later, wanted the youngster to stay another season. Specifically, they wanted him to play with Jadon Sancho.

The two young stars are equally enthusiastic about each other. Pulisic reckons Sancho has “incredible technical ability, with skilful, shifty movement”. Sancho says, “When Pulisic plays, everything seems so simple and normal. I want to be like that, too. He’s only two years older than me, but from what he has already achieved with the USA, despite the huge pressure on him, he is an inspiration for me.”

In 2018/19, under yet another new boss, Swiss coach Lucien Favre, a brilliant young Dortmund side again realised their potential with their early form, winning 12 and drawing three of their first 15 league games while Bayern surprisingly floundered. But the season didn’t work out as Pulisic hoped.

“I had a great start but a few injuries, and it became frustrating for me,” explains Pulisic, who ended up playing 90 minutes only once between Dortmund’s sixth and 26th league games. He felt that the coach was looking to the future, a future where he didn’t feature, but then Dortmund took advantage of Bayern’s poor start to the season and were top until they were overtaken in March. A 5-0 defeat to Bayern in April 2019, which Pulisic sat out injured, put yet another title all but in the hands of the Bavarians. Pulisic played 90 minutes in each of the final three games, scoring in two and assisting Marco Reus for BVB’s final goal of the term. They were also beaten home and away by Spurs in the Champions League last 16.

Bayern had saved their best for the run-in, losing only once after mid-November. “They were as good in the second half of the season as we were in the first,” says Pulisic. “It was a shame we couldn’t win the Bundesliga, but when I spoke to the fans before my final home game, I told them that we’d given everything. I also told them that, after five years in the city, Dortmund would always be a home for me.”

He did this with a microphone as he faced the vast Sudtribune, the 26,000-capacity terrace – football’s biggest.

“I’m not emotional but I was that day,” he says. “I stood in front of all those faces and spoke to them in German before the game, then I struggled to get it together, because I was crying in the tunnel when I returned to the dressing room. They sang my name one last time. It wasn’t easy to leave Dortmund.”

But leave Dortmund he did, after 127 first-team games, 19 goals and 26 assists.

Pulisic continues, “It has long been a dream to play in England, and Chelsea was one of the clubs I knew when I was growing up in the US – I watched players like Frank Lampard. I had a gut feeling that Chelsea was the right choice. It’s pretty cool that Frank [is] my coach – and Chelsea have a great squad.”

A two-window FIFA transfer ban means the American was Chelsea’s only signing. Some see him as a successor to the departed Eden Hazard. Their styles, though, are very different.

Before he joined up with Chelsea’s pre-season in Japan, cutting short his holidays to do so, Pulisic played for the USA in the Gold Cup, where he reached his first international final (which ended with a 1-0 defeat to Mexico in Chicago). Pulisic scored twice in the semi-final against Jamaica and was named the young player of the tournament.

“We’ve got some very young players and I did my best to help them settle,” he says, sounding like a senior pro rather than someone born in 1998.

“I remember players like Geoff Cameron helping me to settle by inviting me out for dinner and making me feel part of the team – or by doing pranks on me, like turning my bed turned inside out – and I always wanted to be someone who helped others.”

Yet, despite Pulisic, the USA have badly – and very publicly – underachieved. They missed out on the 2018 World Cup in Russia by finishing fifth in the Hex, the final six-team CONCACAF qualifying group which they’d won in 2006, 2010 and 2014. Losing both games to Costa Rica and drawing in Honduras and Panama meant that the US entered their final fixture, away to Trinidad & Tobago, needing at least a point to guarantee qualification. Pulisic scored but Trinidad & Tobago, who had taken three points from their other nine matches, won 2-1. Due to results elsewhere, the USA didn’t even reach the fourth-place consolation prize of a play-off against Australia. It was a humiliating, almost unimaginable failure.

“I was in tears after the game, when we realised we wouldn’t be going,” says Pulisic. “It was tough. It was, and still is, a dream to play in a World Cup. I wanted it so bad.”

It took the US over a year to name a new permanent manager, to Pulisic’s bafflement. “At the time I struggled to understand why, but maybe everything happens for a reason,” he says, diplomatically, before adding, “We have some very good players.”

Pulisic’s future is bright for club and country alike. He has already played 34 times for the USA, scoring 14 goals. In the Gold Cup, he looked a level above any of his team-mates.

In October, his Chelsea career ignited with a 35-minute perfect hat-trick at Turf Moor. If Pulisic's trajectory to date is anything to go by, they will be the first of many goals in royal blue.

While you're here, why not take advantage of our brilliant subscribers' offer? Get the game's greatest stories and best journalism direct to your door for only £9.50 every quarter. Cheers!

NOW READ...

INTERVIEW Andy Mitten with Sergio Romero: "Of course it’s best to play all the time... but I'm always ready"

QUIZ Can you name every player to score 10+ Premier League goals for Liverpool?

GUIDE Premier League live stream best VPN: how to watch every game from anywhere in the world

Andy Mitten is Editor at Large of FourFourTwo, interviewing the likes of Lionel Messi, Eric Cantona, Sir Alex Ferguson and Diego Maradona for the magazine. He also founded and is editor of United We Stand, the Manchester United fanzine, and contributes to a number of publications, including GQ, the BBC and The Athletic.