The football team destroyed by the Chernobyl disaster: FC Pripyat

FC Pripyat were preparing for a cup semi-final and move to a new stadium in April 1986 when Chernobyl changed everything. Their former captain recalls how a progressive town and its football team came to an abrupt, tragic end

We've also done a podcast version of this story, for your pleasure. Please subscribe and give us a lovely review on iTunes – we'll be your best friends.

On the morning of Saturday April 26, 1986, a helicopter landed on a football pitch in northern Ukraine. Players from FC Pripyat were preparing for a big cup semi-final against FC Borodyanka later that afternoon.

They watched as men wearing protective suits and carrying radiation detectors clambered out of the helicopter. As the detectors clicked with audible warnings, the men informed the footballers that the match would not be played. There had been an incident at the nearby Vladimir Ilyich Lenin Nuclear Power Plant, also known as Chernobyl.

Pripyat was a commuter town located a couple of miles from the nuclear power plant and around 10 miles from the city of Chernobyl. Founded in 1970, it was a modern and progressive “atom town”, designed to represent the best of the Soviet Union – the now-defunct state that encompassed 15 republics including Russia and Ukraine.

Pripyat had a cinema, swimming pool, amusement park and several tower blocks that housed a population of around 50,000. It also had a football team called FC Stroitel Pripyat.

‘Stroitel’ means builder. The team was formed by men working on the construction of the Chernobyl plant and town of Pripyat, with support from Vasily Kizima, the director of construction. Sport played an important role in Soviet society and was incorporated by the state into the daily lives of its citizens. “I have people working in four shifts, and there’s no place for them to go and rest,” explained Kizima. “Let them go and watch some football and drink some beer.”

Pripyat’s’s modest ground stood in the shadows of the residential blocks. The pitch was surrounded by a running track, with a hut for a dressing room and a small wooden stand. The stadium was often full of spectators, even with the club in the amateur fifth tier of the Soviet football league system. “In Pripyat, everyone loved football,” defender Alexander Vishnevsky told Soviet Sport. “Two thousand of them came to watch.”

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Visible in the distance beyond the boundary fence was the 500ft-high chimney stack of Chernobyl’s Reactor No.4.

Chernobyl opened in 1977 and Pripyat became a works team as a result. The side’s youngest player, Valentin Litvin, didn’t yet work at the plant as he was still at school. Litvin was one of six brothers – all of them decent players – and born in the nearby village of Chistogalovka. He studied in Pripyat.

“I remember one episode in the ninth grade,” says Litvin, speaking to Valeriy Shkurdalov of Discover Chernobyl. “I was taking an algebra exam, and I was supposed to play in a game. Our teacher looked out the window and said, ‘Who are they waiting for?’ There was a bus and the team was waiting for me, all of them grown men.”

In 1978, after graduating from school, Litvin began working as an engineer at Chernobyl. Like most Pripyat players, he was paid a small football allowance – two roubles and 50 kopecks (worth about £3.25 today) for district games and five roubles (£6.50) for regional matches – on top of his power plant wage. But some of his team-mates were ringers, brought in from around the region specifically to play football.

“These were called ‘snowdrops’,” says Litvin. They were named this because, like the flowers, they arrived late in winter. “They received salaries from the power plant and were listed on the payroll, but they didn’t do any work.”

Backed by the power plant, and with snowdrops among their ranks, Pripyat pushed for promotion to the professional fourth tier. In 1981, they appointed former USSR striker Anatoliy Shepel, a league and cup winner with Dynamo Kiev, as manager. “That was the moment when our team began to take shape,” says Litvin, who became the captain. Pripyat, playing in white shirts and blue shorts, won the regional cup competition in 1981, 1982 and 1983, but struggled in the league and remained stuck in the fifth tier.

In 1986, the club built a new ground – the Avangard Stadium – with better facilities, floodlights and a large covered stand. Once finished, it would hold 11,000 fans. At the time, the authorities were planning to build a fifth reactor at Chernobyl. “The stadium is as important for the city as the reactor,” said Vasily Kizima.

The ground was due to officially open on May 1, 1986, but before that, Pripyat were scheduled to play a cup semi-final against Borodyanka on April 26.

At 1.23am that morning, Chernobyl’s No.4 nuclear reactor exploded. People in Pripyat saw a flash and heard a bang; raging fires could be seen through the darkness, and firefighters were dispatched.

This wasn’t the first incident at Chernobyl (a partial core meltdown had occurred in 1982), and it was assumed that it would soon be over. The locals stood outside to watch the fire as ash dropped from the sky. After sunrise, with the fire dampened, they got on with their lives. They went shopping, made preparations for the May Day parade, and headed to their football ground for the big match.

Valentin Litvin had spent the night with family in Yampol, several miles away. His wife was in hospital in Pripyat due to complications following the birth of their second child, and the family was looking after the baby. He returned to Pripyat for training at 9am and was stopped by police at the entrance to the town. “I asked them what had happened, but they didn’t know anything,” he says. “So I crossed the bridge and went to the stadium.”

The sun was shining, and Litvin recalls seeing people strolling past with their children. A street vendor was selling vegetables. All of them were unaware that Chernobyl had experienced the worst accident in the history of nuclear power. The only real indication that something was wrong was the sight of slow-moving vehicles from the plant, spraying roads with decontaminant. Pripyat would not be evacuated for 36 hours.

At the stadium, Litvin met the other players and coaches who told him that Borodyanka’s squad had been stopped well outside of Chernobyl. So Litvin went to the team headquarters, located in a nine-story tower block, to find out if the match was off. Shortly after he got there, one of the coaches turned up and told Litvin about the helicopter landing on the pitch. He went up onto the roof. “I could see the nuclear power plant,” he says, “and the smoke rising above the ruins of Reactor No.4.”

Litvin’s thoughts switched from football to his wife. He rushed over to the hospital, where she told him what had happened the previous night. “Of course, she hadn’t seen everything,” he explains. “There was noise, fuss, doctors running across the building looking for infusion sets which they were short of, and victims arriving one after another.”

His wife couldn’t be discharged, so “we had to stage an escape”. Litvin helped her climb out through a ground floor window. “We saw patients from the hospital standing on a hill, where they had a good view of the plant and could watch as helicopters dropped materials into the destroyed reactor.”

The pair left Pripyat on a motorcycle, passing long queues of empty buses. “They were waiting for the command to come into town and start the evacuation,” says Litvin. “The background radiation level was already very high. The buses didn’t arrive until noon the following day, April 27.”

The Soviet Union tried to keep the accident at Chernobyl a secret, even from its citizens. “The information, apart from being unavailable, was unbelievable,” continues Litvin. “I, like many others, believed the reactor simply couldn’t explode.”

The outside world eventually heard about the accident on April 28, when high radiation levels were detected 800 miles away in Sweden.

The Chernobyl disaster released at least 400 times more radioactive material than the Hiroshima bomb. A 19-mile exclusion zone was set up around the plant and the people of Pripyat were never allowed to return to their homes, with many relocated around 30 miles away to the town of Slavutych.

Several Pripyat players, including Alexander Vishnevsky, set up a new club called FC Stroitel Slavutych. Valentin Litvin ended up in Obukhov and began playing for FC Zarya Vladislavka.

Another evacuated footballer was future Milan and Chelsea striker Andriy Shevchenko, then a nine-year-old at Dynamo Kiev’s academy. Kiev was the nearest major city to Chernobyl, so Shevchenko and the rest of the kids were taken 250 miles south to a training camp on the Black Sea coast. Despite everything, football continued.

On May 2, less than a week after the accident, Dynamo Kiev played Atletico Madrid in the European Cup Winners’ Cup final in Lyon. “As far as the events of Chernobyl go,” Dynamo coach Valeriy Lobanovsky told the press, “my players were aware of it but not disturbed in their preparation for the match.” Dynamo, with a side including Soviet stars Oleg Blokhin, Vasili Rats and Igor Belanov, beat Atletico 3-0.

Back at Chernobyl, there was a lot of important work to be done. Both Alexander Vishnevsky and Valentin Litvin acted as ‘liquidators’ during the recovery and clean-up operation. Litvin helped decontaminate the power plant’s basements, where high radiation levels allowed only a few minutes of exposure, and deadly pieces of graphite from the exploded reactor core fell from the roof above.

The liquidators carried radiation maps and dosimeters to limit their exposure, but Litvin says they often had to exceed safety limits to get the job done. Around 600,000 men and women were involved in the clean-up, which was brave and dangerous work that ultimately saved much of Europe from becoming uninhabitable.

One liquidator, helicopter pilot Eduard Korotkov, recalled circling over the damaged reactor for two hours each day that summer, then watching football on television at night. “The World Cup was on,” he revealed in oral history book Chernobyl Prayer, “so we talked a lot about soccer.” According to Soviet Sport, in the aftermath of the disaster, “football was the only comfort for the people”.

The Soviet side in Mexico included Dynamo Kiev triumvirate Blokhin, Rats and Belanov and was led by Dynamo boss Lobanovsky, who again tried to play down an event that remained shrouded in Soviet secrecy. “I think our government has given out all the facts to reporters about what really happened, after the campaign spread by the international press,” he said. After thumping Hungary 6-0 and topping their group, the Soviets lost 4-3 after extra time to Belgium in the last 16, despite a Belanov hat-trick in Leon.

FC Slavutych, the successor to FC Pripyat, had a short-lived existence. The new outfit competed in the amateur league in 1987 and 1988, but then disbanded.

Players and fans had been dispersed all over the region, and many were preoccupied with the liquidation of Chernobyl. A large number of people from Pripyat and the exclusion zone became sick and died, and while the official Soviet death toll from the accident is 31, other estimates place the figure significantly higher.

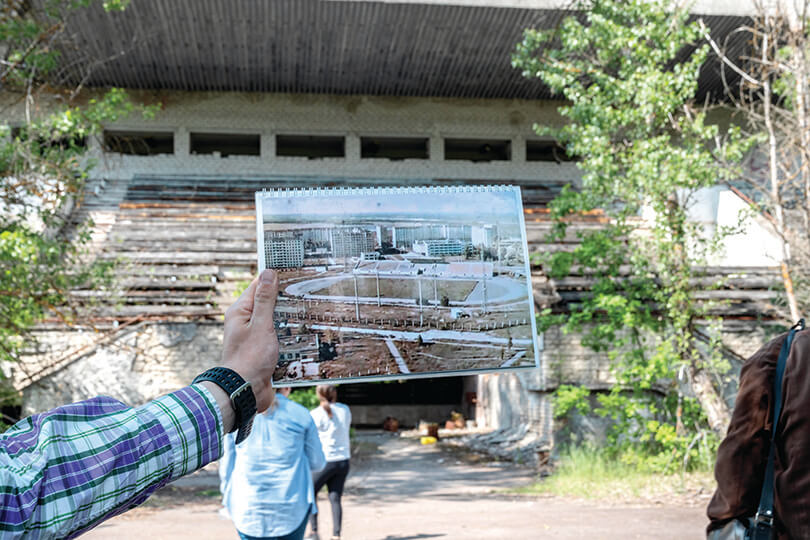

Today, Pripyat’s never-used Avangard Stadium stands as an unusual tourist attraction; the floodlights rusted and pitch overgrown, inside a radioactive ghost city being reclaimed by nature. Valeriy Shkurdalov runs the Discover Chernobyl Facebook page and works as a tour guide in Pripyat and the exclusion zone.

“The stadium is often visited by tourists,” he tells FFT, “although the field is covered by trees.” One visitor Shkurdalov took into the exclusion zone was Valentin Litvin, now a pensioner but still playing football and refereeing locally. It was the first time he had been back to Pripyat.

The Chernobyl clean-up project is scheduled to finish in 2065 and experts believe the exclusion zone will be contaminated for another 3,000 years. No one’s going to be playing football in Pripyat any time soon.

Pictures:Discover Chernobyl, Valeriy Shkurdalov, Valentin Litvin

This feature originally appeared in the September 2019 issue of FourFourTwo. Get 5 issues of the world's greatest football magazine for £5 – the game's greatest stories and finest journalism direct to your door for less than a pint in London. Cheers!

NOW READ...

LIST Harry Kane and 20 other players who LOVE scoring against one club

FROM THE MAG The bizarre history of football-inspired names: from German Kevins to the 600 Brazilians called Lineker

WATCH Premier League live stream 2019/20: how to watch every game from anywhere in the world