China's football masterplan: why there's much more to it than stellar signings

John Obi Mikel, Carlos Tevez and Oscar are the latest household names to flock to the Far East for lorryloads of cash – but there's more to the country's development than splurging sizeable sums on established stars

"Financially speaking, the Chinese Super League already beats second-tier European leagues such as Portugal and the Netherlands,” says Joseph Lee, the Indonesia-born, Brazil-based agent who has overseen many of the recent transfers between Brazil and China.

“China has grown up financially and has the biggest population of any country in the world – and 20-30 per cent of these people are into football. If we can get them into the stadiums, we’ll have the biggest crowds in the world.

“Japanese football had to wait decades to establish itself internationally, but that’s the goal Chinese football should pursue – to become a reference point in world football.”

Hey big spenders

It all adds up to a concerted push for the world’s second-biggest economy to achieve a similar ranking in the world’s biggest sport

That process is now well under way. In November 2015, 50,000 Guangzhou Evergrande fans went potty as their team won the AFC Champions League – at that point, their second continental triumph in three years, to go with five successive domestic titles. The celebrations lasted long into the night, but the next stage of their masterplan – to challenge on the global stage by winning the FIFA Club World Cup, and then eventually become one of the top 10 clubs in the world – was already in place. Guangzhou were the first club in China to start spending serious money, and as recent events have shown, they are far from the last.

On the face of it, the ‘Great Haul of China’ is down to a growing number of teams wanting to make headlines globally and win trophies locally. Among the established names to move to the Chinese Super League in 2016, following Demba Ba and Paulinho the previous year, were Fredy Guarin, Jackson Martinez, Ramires, Gervinho and Alex Teixeira (those five joining four different clubs). John Obi Mikel, Carlos Tevez and Oscar have headed east more recently, and if media reports are to be believed there's plenty more to come.

Oscar has arrived to China after completing his £52M move to Shanghai SIPG. pic.twitter.com/fry5QNGZU7— Seleção Brasileira (@BrazilStats2) January 2, 2017

“Buying famous foreign players helps the clubs to improve quickly,” says Montenegro international Dejan Damjanovic, who joined Jiangsu in 2014 and, later, Beijing Guoan. “For a long time, China wanted to compete with South Korea and Japan; now they want to compete with everyone. Jiangsu weren’t one of the giants of Chinese football, but there is potential for them to be a big club.”

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

But the spending on transfers is just one part of the grand plan. The clubs are driving that improvement in the short term, but there’s plenty more going on in the long term. It all adds up to a concerted push for the world’s second-biggest economy to achieve a similar ranking in the world’s biggest sport.

In a hurry

The president already warned us that our main goal is to leave a legacy for local football – not just take the money, bring in three or four players and leave nothing for China

When it comes to politics and diplomacy, the Chinese long game – the slow, chess-like moves that supposedly reap dividends years and decades down the road – is mentioned in hushed tones by international relations students and columnists around the world. There is less patience when it comes to the global game. China wants to be the best, or one of the best, in football – and the sooner the better.

“We don’t work with a budget,” said Gabriel Skinner, Tianjin Quanjian’s Brazilian (since-departed) assistant manager. “If we need anything, we forward our request to the president – he has given his full support so far. During pre-season in Brazil, we needed to buy equipment for the players that cost $1 million. It didn’t take more than a few minutes for him to approve the order.

“The president already warned us that our main goal is to leave a legacy for local football – not just take the money, bring in three or four players and leave nothing for China.”

The amounts of money being spent continue to increase, but China has been spending since 2010 – when property developer Evergrande took over Guangzhou, a club that had previously been relegated due to involvement in match-fixing.

Over the previous decade or so, the Chinese Super League had been known for that: corruption, not untold riches. There were periodic scandals, forcing sponsors and fans to turn their backs, but in recent years there has been a determination to tidy up the game. The government, which had long focused its efforts on producing stars in table tennis and gymnastics (find the right prospect, give them lots of training, sit and wait for the gold medals to roll in), knew the first step to development in football was to make it clean.

Cleaning up their act

With the drive to improve coming from the top, those who do their bit will – so the theory goes – gain the gratitude of those in power

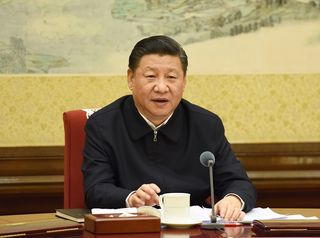

The punishments were draconian. In 2009, officials, referees and ex-players got their dues. In 2012, two former heads of the Chinese FA were jailed for a decade each. It had been known for some time that Xi Jinping was destined to be president (he was elected the following year) and it was also known that he wanted an end to years of underachievement in the game. He wants China’s sports industry to be worth £590 billion. Then comes hosting the World Cup, in the decade after next, and winning it, perhaps in the decade after that.

Not all the clubs care about that so much, claims Titan Sports’ Ma Dexing, one of the country’s leading football journalists. “They just want to win games and titles,” he says, “and the bosses think that buying famous foreign players is the best way. How much it costs is not important.”

Ma believes that much of the spending is being done to curry favour with the government and politicians, either of the regional or national variety. With the drive to improve coming from the top, those who do their bit will – so the theory goes – gain the gratitude of those in power.

At the moment, Guangzhou are the best side in Asia, although they’re now being pushed at home as other clubs spend big as well. There have been worries (or should that be hopes?) expressed in Europe that the spree is not sustainable.

This is one of the world’s largest economies, however, and one that thinks nothing of building stadiums in Africa or high-speed railways in Southeast Asia – there’s more than enough money to finance the purchase of a few high-profile Brazilian footballers. Financial experts don’t foresee too many problems, even if there's a slowdown in the economy. China has the resources and, more importantly, the political will.

Corporate backing

Evergrande made huge money from the property boom in the big cities but have branched out into all sorts of businesses

Simon Chadwick, Professor of Sports Enterprise at Salford University and long-time observer of Chinese football, believes the spending will continue. “Some of the money is coming from the state,” he says, “especially at the provincial level. Much of what is being directed into football, though, is coming from the corporate sector – particularly from China’s entrepreneurial lieutenants, who must be seen to be supporting the state.” This is a view backed by Tim Cahill, who was until August 2016 one of the biggest names in the league. The former Shanghai Shenhua and Hangzhou Greentown star has predicted that a $100m transfer is not too far away.

The investment does not come from a single source. Evergrande made huge money from the property boom in the big cities but have branched out into all sorts of businesses – they have previously annoyed the Asian Football Confederation by using their own brand of bottled water during Champions League games.

And not every club’s owners have the same real estate background. The 2015 runners-up, Shanghai SIPG, are backed by the Shanghai International Port Group (who run the public terminals in the Port of Shanghai); Jiangsu, previously a nondescript mid-table outfit, were bought by retail giants Suning; Shandong Luneng, 14th (of 16) last season, are run indirectly by the State Grid Corporation of China – the largest electricity company in the world.

While political connections do matter, for some it is good for the brand – such as Suning, who took over Jiangsu in 2015. The purchases of Brazilians Ramires and Alex Teixeira (and to a lesser extent, Jo) have inserted the name of Suning, who have more than 1,000 stores all over China, into a global conversation. There is the possibility of making some money, too. Evergrande paid just £11m for their club in 2010 and then proceeded to invest. In 2014, they sold a 50 per cent stake to Alibaba, a giant e-commerce site, for £127m.

Next page: “It's the worst decision that has been taken since I’ve been here – you can’t allow a sponsor to bring in a player”

Investing overseas

Brazilians, especially, have long been popular in East Asia and there is a well-worn route from Sao Paolo to Shanghai, Seoul and Sapparo

The country is also getting involved overseas. Jackson Martinez moved when a Chinese club paid big money to a part-Chinese-owned Spanish club, Atletico Madrid. The news from Portugal in 2015 that, due to the second division’s Chinese sponsor, there would be starting places for 10 Chinese players in the top teams may have been reversed, but it shows there's always at least one eye on the improvement of football back in the motherland.

Something similar has happened before. When Everton signed Li Tie in 2002 they were surprised to find that he was part of a package containing Li Weifeng. In July 2015, Rayo Vallecano signed Zhang Chengdong because they had a Chinese sponsor. Coach Paco Jemez was none too pleased, calling it “the worst decision that has been taken since I’ve been here – you can’t allow a sponsor to bring in a player.” Zhang was back in Beijing by the end of the year.

It remains to be seen what happens with the Chinese investment in City Football Group to buy a 13 per cent stake for around £275m but once again, the benefit of Chinese football will be paramount in the minds of the buyers.

In the meantime, the movement of players will still be mostly eastward, and mostly they’ll be South American. Brazilians, especially, have long been popular in East Asia and there is a well-worn route from Sao Paolo to Shanghai, Seoul and Sapparo.

Samba style still excites in this part of the world, and players have always been willing to travel – the agents, the network were in place. These days there is just a better quality of player heading there, due to bigger amounts of cash on offer. The debate in Brazil is whether the exodus (four of Corinthians’ 2015 title-winning team were in China last season) is good for the players and their role in the national team, but the hope in Beijing is that better foreign players will raise the level of the locals.

Local development

Every time a Chinese club takes to the pitch there must be seven local players, although there have been rumblings of some of the bigger clubs seeking to change this rule

“The good foreign players who aren’t in China just for the money are happy to help Chinese players improve,” says Damjanovic. “The Chinese players are still not as good as Korean or Japanese players, but the gap will become smaller.” Guangzhou’s local lads have certainly developed, although that may well have happened anyway – after all, playing under coaches such as Marcello Lippi and Luiz Felipe Scolari will have made a difference.

The foreigners’ power is limited, however. Chinese teams can buy only five foreign players each. One must be Asian, and only three of the four others can play at any one time. Every time a Chinese club takes to the pitch there must be seven local players, although there have been rumblings of some of the bigger clubs seeking to change this rule.

For the moment, to challenge at the top you need some good local talent, and fans of Jiangsu, while excited about the big names, are slightly perplexed at the club’s new-found wealth and the seemingly scattergun approach to signings. “It's exciting in one sense but we don’t seem to have a strategy,” says Luo Ming, a Jiangsu fan. “We’re just trying to sign any foreign player who is famous. It doesn’t matter how good these foreign players are if you don’t have good Chinese players.

“We sold our best local player and haven’t replaced him. Many teams in China now have good foreign players; we need to focus on domestic players, as that’s what will make the difference.”

Little demand for exports

China does not send players to the big leagues of Europe, as South Korea and Japan do, simply because the country has not yet produced the required talent

The current contingent of Chinese players is not good enough to challenge for global supremacy. China does not send players to the big leagues of Europe, as South Korea and Japan do, simply because the country has not yet produced the required talent.

Guangzhou’s Zhang Linpeng could be an exception: interest from Chelsea and Real Madrid may be an attempt to win support in the Middle Kingdom, but the defender is good enough regardless. At the moment, though, there aren’t many others who are. But this generation of players came through an erratic development system with often mediocre coaches, sub-par facilities and an uncaring government.

That has always been a problem – but there was a bigger one. Despite the talk of 1.3 billion people surely producing a top-class XI sooner or later, people just don’t play the game. In 2010, the stats said there were fewer than 10,000 registered under-12 players. Japan, with a tenth of the population, boasted 300,000. This was the real reason for underachievement. Walk around Beijing or Shanghai and you don’t see kids on the street or in the park kicking a ball about. Parents just didn’t regard football as a viable career path for their children.

In November 2014, the Ministry of Education announced that football would be compulsory in Chinese schools. Officials are ensuring that by next year, 20,000 schools will have new football pitches and training facilities, with the ambitious aim of creating 100,000 new players. Clubs such as Guangzhou have invested in their facilities and academies, and the government is to build pitches all over the country.

A country going places

Tom Byer is a youth development expert employed by the Chinese government as a consultant for the programme. “The Ministry of Education applied for 350 million RMB (around £37m) from the National Financial Department,” he says. “All of the provincial Education Bureaus are also putting in significant amounts. There are lots of activities going on, along with many sponsors who are investing as well.”

The 1966 World Cup was fixed… and 27 other crazy football conspiracy theories

Inside Jurgen Klopp's Liverpool: the secrets of the Reds' German genius

The secret lives – and hilarious stories – of football's player liaison officers

The long read: Guardiola's 16-point blueprint for dominance - his methods, management and tactics

Going forward, kids will have many more advantages. Football was always popular, but the league is booming. The 2016 TV deal for the Chinese Super League was worth around £132m – some jump from £1m in 2015. More money is coming, attendances are rising (which fell just short of the 25,000 average mark last season), salaries for local players are growing and the profession will start to look a little more attractive for kids and parents.

Throw in the better facilities, the greater quality and quantity of coaching, and regular school football, and more children will be playing the game. One problem that needs to be solved, however, is that most of the foreign talent being signed will fill creative positions, leaving none for the locals. The goalscoring charts will be mainly foreign, which could well be an issue for the national team in years to come.

If this can be addressed, the future is bright. Amid all the spending, this is the bigger picture, the long-term game: producing better Chinese players and making China a world power. Watch this space.

Additional reporting: Marcus Alves

This feature originally appeared in the April 2016 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe!

John Duerden has covered Asian sport for over 20 years for The Guardian, Associated Press, ESPN, BBC, New York Times, as well as various Asian media. He is also the author of four books, including Rovers Revolution: Blackburn's Rise from Nowhere to Premier League Champions and Lions and Tigers: The Story of Football in Singapore and Malaysia.