Civil war, Sisyphus and diphthongs : Why Newcastle vs Sunderland is more than a game

In July 2003, Jonathan Wilson and Paul Brown despair about the apparent gulf between recently relegated Sunderland and Champions League-chasing Newcastle...

First, the Sunderland viewpoint, from Jonathan Wilson...

The first thing you see when you pull into Sunderland station is the city crest and beneath it the motto Nil desperandum, auspice deo – ‘Don’t despair, trust in God’.

It is an oddly depressing message, accepting that things will, as a matter of course, be bad. But in Sunderland they usually are.

The crest bears a sextant – a symbol of the city’s shipbuilding past. The last shipyard closed in 1988. The football club’s badge used to depict a ship; now industry is represented by a pit-wheel. The last mine closed in 1994. The club itself is one of only three PLCs that remain on Wearside, but relegation was followed by news of debts of £26.5 million.

There’s a depression around the place. I’ve heard stories about productivity dropping and workers taking sickies. The club has an enormous impact on the life of the city

“There’s a depression around the place,” says Jim Slater, Sunderland’s commercial director. “I’ve heard stories about productivity dropping and workers taking sickies. The club has an enormous impact on the life of the city.”

Indeed, a North East region public health survey revealed that death rates of football fans from stress-induced strokes and heart attacks are over twice the average among Sunderland supporters.

And what really sticks in the craw is that now, 14 miles up the road, Newcastle United, their mediocrity for so long a consolation on Wearside, are thriving in the Champions League, winning friends across Europe and reflecting the optimism that abounds in the city.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Earlier this year I interviewed Ajax’s South African wunderkind Steven Pienaar. He was born in the slums of Cape Town, but supports Newcastle because of the attacking football they play. Does nobody remember that the FA had to change the offside rule in 1925 because Newcastle had become so adept at the offside trap that it was killing the game?

If they do, it seems, nobody outside of Wearside holds it against them. Newcastle’s economy is booming, the American Tourist Board named it in the top 10 party cities in the world and it’s down to the last six to be named European Capital of Culture for 2008. Sunderland doesn’t even have a cinema.

Northern soul

The North East is only 50 miles long and 20 miles wide, even if you stretch the boundary to Ashington in the north and Teesside in the south. (Middlesbrough, incidentally, simply doesn’t count. Newcastle and Sunderland are the sixth and seventh most successful sides of all time in English football; Middlesbrough have never won anything. Boro are like a stone in your shoe – irritating, but of little consequence.)

Middlesbrough have never won anything. They are like a stone in your shoe – irritating, but of little consequence

To the north there is 100 miles of moorland before you reach Edinburgh, to the east the North Sea, to the west the wilderness of the Pennines, and to the south nothing until Leeds. Little wonder it has the most unique identity of any region of England (with the possible exception of the equally remote Cornwall).

When Sir John Hall speaks of the ‘Geordie Nation’, he is talking nonsense, but it is nonsense with a grain of truth. Unfortunately his nonsense also helps to propagate the fallacy that all people from the North East are Geordies. This is a major source of grief. There are three rivers in the North East.

If you’re from near the Tees, then you’re a Teessider, from Wearside a Mackem and from Tyneside a Geordie. Mackems say ‘mak’ when they mean ‘make’ (hence the name; Geordie sounds something like ‘myek’), but the easiest way to distinguish Sunderland from Newcastle accents is the diphthongs Mackems pronounce ‘school’ as ‘skewel’ to Geordie ‘skiil’, while ‘sweet’ sounds more like ‘swayt’ on Wearside.

As Wren raiders will point out, there is good evidence that ‘swayt’ is how the word was pronounced in the 16th century, and they, therefore, are right. This is the kind of argument you hear a lot in the North East – petty, parochial and slightly absurd. The Theatre Royal in Newcastle may have an RSC residency every year, but we win because we have the Empire, which is haunted by the ghost of Sid James.

In his book The Far Corner, which gets as close to explaining the North East as anything, Harry Pearson recalls two men almost coming to blows on a train in an argument over whether Sunderland or Newcastle has the better shopping facilities.

Football crazy

Mostly, though, people argue about football. It is easy to mock the cliché of the North East as a hotbed of football, but no other English region has produced anything like as many great managers – Clough, Paisley, Revie, Kendall, Robson... I moved away from Sunderland eight years ago, and one of the first things I noticed was how little everyday conversation the rest of the world devotes to football.

You can’t walk down a street in Sunderland without seeing a replica shirt; 77% of season-ticket holders at the Stadium of Light - the highest proportion in the Premiership - own one

Returning, you realise just how impossible it is to avoid the game in the North East. On every bus, in every pub, in every shop, the main topic of conversation is football.

You can’t walk down a street in Sunderland without seeing a replica shirt; 77% of season-ticket holders at the Stadium of Light – the highest proportion in the Premiership – own one, even though a 2001 survey showed Sunderland fans to have the lowest average income of any in England.

The place lives and breathes football. As you drive north on the A19, just south of Sunderland you pass the offices of the local newspaper, the Sunderland Echo. High on the wall, drawn out in neon lights, is a football with legs, arms and a cap.

On a matchday, if Sunderland have won, the ball-man will be smiling; if they’ve lost, frowning; if they’ve drawn, somewhere in between. This is how much football means; in the days before car radios, it was seen as necessary to broadcast the score to people as soon as they got to the edge of town.

In an area where football is the number one talking point, it is only natural that it’s through football that the hostility between Sunderland and Newcastle should most obviously manifest itself. “I’ve played in the Glasgow derby,” says Sunderland midfielder Claudio Reyna, “and this is as close as you can get to that level of intensity.”

NEXT: 1400 years of bickering

1400 years of bickering

The cities have been bickering for 1400 years. Founded by the Romans and with a wider and deeper river (see how the world conspires against us?), Newcastle has always been in the role of older brother, doing everything they could to keep us down.

They claim the early 8th-century monk and first historian of England, the Venerable Bede, was a product of St Paul’s monastery in Jarrow. Bedeworld now draws tourists to Tyneside. Yet he was born at St Peter’s, next to the Stadium of Light, spent most of his life in the library there and is buried in Durham, which clearly makes him ours.

It was in the 17th Century that the real hatred began, as Newcastle backed Charles I in the Civil War, while Sunderland rallied behind Cromwell

It was in the 17th Century, though, that the real hatred began, as Newcastle – largely because of the arrival of a Royalist garrison – backed Charles I in the Civil War, while Sunderland rallied behind Cromwell. Then in 1706, Newcastle deliberately strangled a Bill proposing the dredging of the Wear to allow the passage of larger ships, something that would have threatened their domination of the coal-export trade in the region.

Permission was eventually given 15 years later, beginning two-and-a-half centuries of industrial rivalry that frequently spilled over into rioting. The sense remains on Wearside that Newcastle keeps on cheating us.

Clark of the caught

And the sense of betrayal exists in football too, the most significant recent example being the Lee Clark incident. Clark, a Geordie to the core, signed for Sunderland in 1997. He was treated with suspicion on Wearside, but two seasons of fine performances won fans over.

Then Clark was photographed after watching Newcastle lose the 1999 FA Cup Final to Manchester United wearing a T-shirt bearing the slogan ‘Sad Mackem Bastards’. Unsurprisingly fans were outraged and Clark was sold to Fulham.

"The T-shirt incident is a massive regret,” Clark says. “But although we’d won promotion, I had already told Peter Reid, the manager, that I was thinking of moving. In hindsight, joining Sunderland was a mistake because of my background. Everyone knows I’m Newcastle through and through.

"When I left Newcastle, the prospect of staying in the North East, close to my family, was the big pull in going to Sunderland. But when we won promotion it dawned on me that really I would have to go to Newcastle the following season as a Sunderland player.

Joining Sunderland was a mistake. When we won promotion it dawned on me that I'd have to go to Newcastle as a Sunderland player. I couldn’t give 100% against the club I love

"I couldn’t go there and give 100% for Sunderland against the club I love and played for. And if I couldn’t do that I’d have been cheating on Peter Reid, the fans and all my team-mates. It’s not a problem at all to go to Newcastle as a Fulham player and giving everything, that would be a very different situation. To understand you have to know the feeling in the North East between the two clubs.”

They may have been bitter, but most Sunderland fans probably understood. Nevertheless, it was another nail in the coffin, another example of Newcastle putting one over on us. So it has been throughout history. At the minute it seems all we can do is try to obstruct their success.

War of words

At the Stadium of Light this season, Sunderland already relegated, took some comfort from the thought that they could scupper Newcastle’s chances of qualifying for the Champions League. The attitude is best grinned up by a song of the mid-’90s:

“F**k ’em all, f**k ’em all / Keegan, McDermott and Hall / We’ll never be mastered by black-and-white bastards / Cos Sunlun’s the best of them all.”

A soft penalty and a disallowed last-minute goal later, and Newcastle were up to third as Sunderland licked the wounds of a 13th straight defeat.

Just outside the Stadium of Light, as the grass falls away steeply to the Wear, there is a sculpture of stick-figures representing the miners who used to work on the site. They resemble nothing so much as Sisyphus endlessly rolling his stone to the top of the hill, only for it to go crashing back down again. Nil desperandum…

NEXT: The Newcastle viewpoint

Now, the Newcastle viewpoint, from Paul Brown...

"Let's all laugh at Sunderland!" is the Toon Army’s favourite Mackembaiting song. And Newcastle United fans have had plenty of recent opportunities.

The underachieving reign of Peter Reid offered easy opportunity for simian-related tomfoolery at the expense of the monkey-faced manager. And Howard Wilkinson’s lamentable stewardship, coupled with his increasingly eccentric post-match interviews, raised humour levels to new and exciting heights.

Despite Sunderland having been relegated two weeks previously, and Newcastle’s title challenge having effectively expired on the same day, fervour remained sky-high for the April Tyne-Wear derby at the Stadium of Light.

Derby days are excellent. There is a buzz in both cities and the level of excitement crescendos in the week beforehand. The rivalry between the two clubs is second to none

“It’s the biggest game of the season, bar none,” says Sir Bobby Robson. “It’s the match every fan looks forward to.”

In the North East, the proverbial hotbed of soccer, you’re the exception if you don’t support your local team. Geordies, so-called because Newcastle stood loyal to King George II during the Jacobite rebellion in 1745, support Newcastle.

Mackems, named from a Geordie insult relating to the shipbuilding industry (‘Sunderland make ’em, other people take ’em’), support Sunderland. It’s in the blood, you don’t have a choice, and it’s as simple as that.

Geordies are also Mags, with Newcastle United the black-and-white Magpies. Sunderland AFC didn’t have a proper nickname until February 2000, when the red and whites plumped for the Black Cats, a decision on a par with their nicking the name Stadium of Light from Benfica. Origins, like everything else in North East football, are subject to argument.

“Derby days are excellent,” says Sir Bobby. “There is a buzz in both cities and the level of excitement crescendos in the week beforehand. The rivalry between the two clubs is second to none."

But how can that be? After all, the clubs aren’t even in the same city. Newcastle’s St James’ Park and Sunderland’s Stadium of Light are 12 miles apart, separated by the A19 and connected by the Metro. (The light railway system was finally extended to Wearside in April 2002, 22 years after disgruntled Sunderland taxpayers first began paying for it.)

Ruud Gullit once commented that the Tyne-Wear derby was inferior to the Milan derby because, he said, the fans don’t live and work together. It wasn’t the only thing he got wrong during his reign at Newcastle. The Dutchman lost his only Tyne-Wear derby and his job when, underestimating its importance, he left Geordie legend Alan Shearer on the bench in a St James’ Park monsoon on a fateful August day in 1999.

After a defeat Mackems are like Saddam’s irregular forces discarding colours, blending back into the local populus, and denying ever being part of the evil regime, but always ready for a snide pot-shot when the opportunity arises

Newcastle and Sunderland fans do work together in both cities. And in the ‘middle ground’ Gateshead, Durham and Washington, Geordies and Mackems live next door to each other. Toon fan Lee Shearer lives in Gateshead, and can see both St James’ Park and the Stadium of Light from the windows of his flat (although he plans to brick up the latter).

“I work in Peterlee with a load of Mackems,” he says. “After a defeat they’re like Saddam’s irregular forces discarding colours, blending back into the local populus, and denying ever being part of the evil regime, but always ready for a snide pot-shot when the opportunity arises.”

The key to the nature of the rivalry between the two sets of fans lies in the rivalry between the two cities, both with their own unique identities, accents and outlooks. While Liverpool and Everton fans are separated by football, they are united by city. Newcastle and Sunderland fans have no such common ground.

NEXT: Poles apart

Poles apart

Geordies see Mackems as jealous that Newcastle as a city has, among other things, an international airport, a national railway station, a cathedral, a major concert venue, a renowned nightlife, a set of famous bridges, Viz comic and Brown Ale. Sunderland has none of these.

Newcastle United haven’t won so much as a Reader’s Digest prize draw for over 30 years. Despite this, they still regularly sell out the 52,000-capacity St James’ Park

Mackems see Geordies as arrogant, particularly since Newcastle United haven’t won so much as a Reader’s Digest prize draw for over 30 years. Despite this, Newcastle still regularly sell out the 52,000 capacity St James’ Park, while Sunderland have yet to fill the Stadium of Light since increasing its capacity to 48,000.

Newcastle have won 10 top-class domestic trophies, compared to Sunderland’s eight. And Newcastle have qualified for major European competitions 10 times, including the Champions League twice, winning the Fairs Cup in 1969. Sunderland have qualified for Europe only once, for the Cup Winners' Cup in 1973, and they were eliminated in the second round.

During Sunderland’s goalless draw with Blackburn earlier in the season, fans cheered the half-time announcement that their relegation rivals West Ham were beating Newcastle. Newcastle actually did Sunderland a favour by fighting back to draw at the Boleyn Ground – news that was met with groans at the Stadium of Light. Sunderland fans would rather have seen West Ham win and increase Sunderland’s probability of relegation than see Newcastle take a point, such is their hatred for Geordies.

Sunderland bags and pin badges proudly bear the initials ‘FTM’, supposedly meaning ‘For The Mackems’, but actually standing for ‘F**k The Mags’. Geordie fans have suggested ‘FTM’ could also stand for ‘Free Ticket Mackems’, in response to the Wearside club’s attempts to fill their ground by offering complimentary tickets to schools, businesses, and care homes across the region.

That scheme was rumbled when kids, inevitably, turned up at the Stadium of Light wearing black and white shirts. By way of a riposte, Newcastle fans have taken to wearing pin badges bearing the initials ‘SMB’ – ‘Sad Mackem Bastards’.

Game day

Although fans can never properly look forward to a derby match because the consequences of losing are so great, the pubs around St James’ Park on the sunny morning of the match are full of grinning Geordies, confidently predicting a famous victory. “I’m worried because I’m not worried,” says Mag Steve Kennedy, as he heads to Ladbrokes to back a Toon win.

Passports are waved, mocking Sunderland’s lack of European experience, and a favourite song from Newcastle’s exciting Champions League campaign is resurrected: “Have you ever seen a Mackem in Milan?”

Forty-five free coaches have been provided to transport most of the 3,500 or so travelling Mags the short distance from St James’ to the Stadium of Light. The convoy is greeted with waves and toots from motorists, and passes various specially-altered road signs (including arrows pointing to the ‘Stadium of Shite’) during the short but slow journey south.

As the Toon Army enters Sunderland, the expected red-and-white horde hurling abuse and volleys of half-bricks fails to materialise. Inside the ground, there's a scrum for the bar, and the singing begins in earnest. A Newcastle fanzine has printed up thousands of black and white banners reading, ‘LET’S ALL LAUGH AT SUNDERLAND! HA HA!’

Mags hold aloft and rattle keys in reference to the Mackems’ diphthong-rich pronunciation ("Weys keys are theys keys?"). Passports are waved, mocking Sunderland’s lack of European experience, and a favourite song from Newcastle’s exciting Champions League campaign is resurrected: “Have you ever seen a Mackem in Milan?”

As the kick-off approaches, Sunderland fans are serenaded with Vera Lynn’s We’ll Meet Again and, with reference to the departed Peter Reid, “You should have stuck with the monkey.” There are hundreds of empty seats dotted around the stadium, in addition to the seats necessarily kept empty for segregation purposes. “You couldn’t sell all your tickets,” sing the away fans.

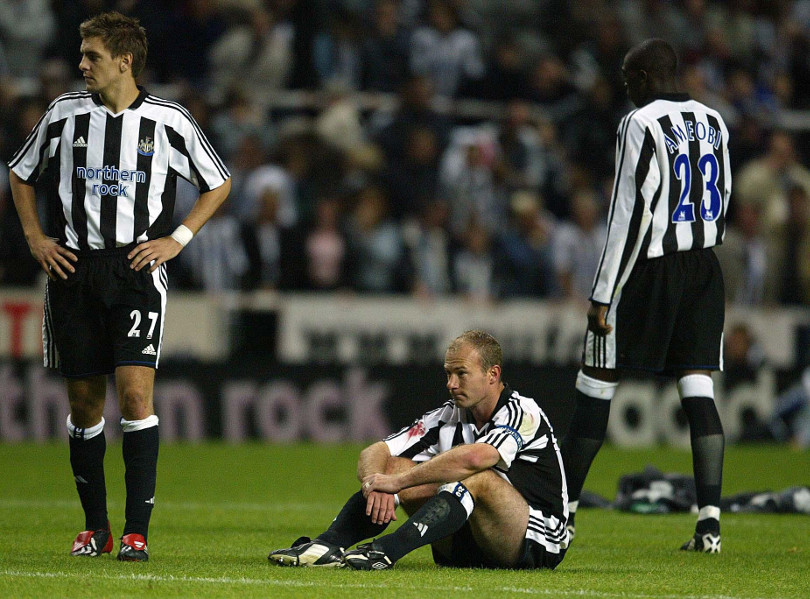

Within seconds of the unusual 3pm Saturday afternoon kick off, a heavily-bandaged Alan Shearer has the ball in the back of the net, but the goal is disallowed for a push. Newcastle’s Shay Given is forced to make a couple of smart saves, but Thomas Sorensen is the busier of the goalkeepers, saving several times from Craig Bellamy.

Despite losing Shearer to injury, Newcastle’s superior pace and skill eventually pay off. Bellamy bursts into the penalty area and is clattered by Kevin Kilbane. It is the clearest penalty imaginable, but, inevitably, 42,000 Mackems disagree. Nobby Solano sends Thomas Sorensen the wrong way from the spot. The Toon Army explode with delight and relief.

Newcastle hold on through the second half until, deep into injury-time, Kevin Kyle rises to head the ball into Shay Given’s net. Scores of home fans excitedly jump barriers to goad the Toon Army, despite the fact that referee Steve Bennett has signalled a free-kick for a foul on Given.

The goal is disallowed, and the game ends 1-0 to Newcastle.

“You’re just the worst team in history,” sing the Geordies, as the Stadium of Light empties. By the time the Toon Army are allowed exit the ground, just three Mackem schoolboys, sipping illegally-procured cans of lager in a bush, remain to half-heartedly flick V-signs at the departing coaches.

“We were on a squeaky floorboard and it was an important victory,” reflects Sir Bobby. “I was delighted at the players’ response.”

So the Toon Army, and Tyne-Wear bragging rights for the foreseeable future, return to Newcastle, leaving a famous valediction ringing around Wearside: “We’ll meet again, don’t know where, don’t know when / But I know we’ll meet again some sunny day...”

Originally published in the July 2003 issue of FourFourTwo

Alasdair Mackenzie is a freelance journalist based in Rome, and a FourFourTwo contributor since 2015. When not pulling on the FFT shirt, he can be found at Reuters, The Times and the i. An Italophile since growing up on a diet of Football Italia on Channel 4, he now counts himself among thousands of fans sharing a passion for Ross County and Lazio.