The craziest season in English football: when the champions got relegated and ‘Lucky Arsenal’ annoyed the nation

Hapless title holders, unlikely contenders at the top and a glut of mid-ranking sides upsetting the established order – the 1937/38 season was mental from start to finish

“If it were possible to stage-manage a football season, skilfully building the actions of the play up to a tremendous climax, that which occurred on Saturday would stand as the perfect example of contrariness.”

Lancashire Evening Post, May 1938

In August 1937, Dixie Dean told the Daily Mail: “This threatens to be the most open campaign we’ve ever seen. Half a dozen clubs stand a good chance of winning it, and any one of 10 clubs could go down.” Dean was right.

Tight finishes at both ends of the table, surprise pacesetters, arguably the worst title winners ever, doping allegations, player meltdowns, the start of the TV revolution and the champions in freefall – all in the tumultuous 1937/38 season.

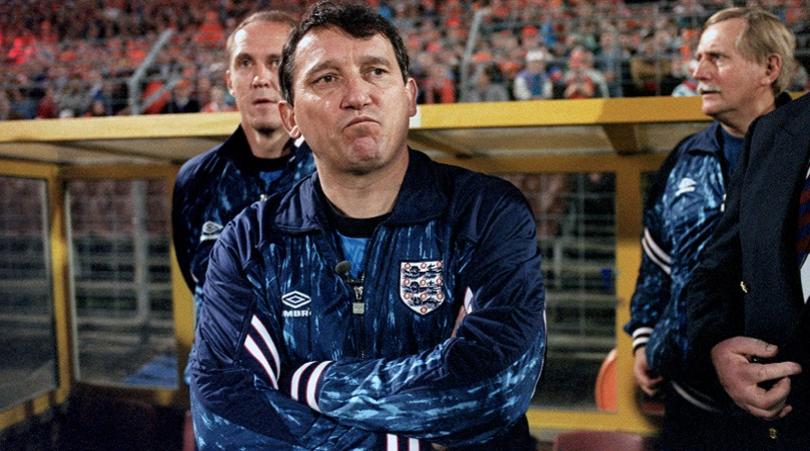

Title favourites were Major Frank Buckley’s Wolverhampton Wanderers, aiming to win the league for the first time. Banned from a pre-season tour due to their ‘over-vigorous’ play the previous season, Buckley’s men – with skipper Stan Cullis setting the standard – buzzed with confidence.

Perhaps it was due to the ‘secret remedy’ Buckley had given his players. In June, Buckley had been approached by chemist Menzies Sharp, who had studied the experiments of French quack Serge Voronoff. The eccentric doctor had made a name for himself grafting the testicles of young sheep and goats onto older ones, claiming the older animals regained their vigour as a result. Believing his players could benefit, Buckley chose to undergo a four-month course of 12 injections taken from monkey glands.

Feeling “hugely invigorated” by the process, Buckley elected to pump his players full of the stuff. Doubters claimed it was a placebo, yet it seemed to work. Only two players, Dicky Dorsett and Don Bilton, refused the treatment and the supposedly monkey-powered Wolves looked to be on their way to a maiden league title.

First, though, they had to wait for a surprise challenge to peter out: that of Brentford, who stayed in the title hunt until the last fortnight of the season. The Times claimed: “London clubs like Brentford and Charlton, whose attendances didn’t suffer due to the economic crises of the early 1930s, could now supplant northern giants like Huddersfield and Newcastle, whose fortunes have declined in the last decade.”

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Buckley, however, was caustic about the Bees from the start, saying: “They’ve done well up to a point, but they won’t keep it going. I don’t think they have the quality or the depth of character.”

After his side defeated Wolves 2-1 at Griffin Park in September, Brentford manager Harry Curtis suggested in reply that Buckley “keep his impertinent comments to himself... I thought they were taught to do that in the army”. Who needs Arsene and Jose?

With inside forward Bryn Jones pulling the strings and striker Dennis Westcott rattling in the goals, Wolves’ form helped them hammer Leicester 10-1 in April. Having heard of their rivals’ monkey gland antics, Foxes officials complained to their MP, Abraham Lyons, who demanded a government inquiry. When Minister of Health Walter Elliot rejected the proposal, Labour MP Manny Shinwell suggested Conservative ministers be put on the gland treatment themselves.

The players had received injections for six weeks at the start of the season, but the effect appeared to wear off at the worst possible moment. In the penultimate game of the season Wolves won their game in hand, meaning a draw away to Sunderland would be enough to pip Arsenal to the title, but they came unstuck at Roker Park, the 10-man Black Cats winning 1-0. “The amount of effort that Sunderland put in was quite staggering,” said Jones. “Anyone would have thought that they had taken energy pills to help them…”

After learning of Arsenal’s title-clinching win at Highbury, several Wolves players dissolved into tears, only to be met by Buckley’s sharp rebuke. “The Major told us only conscientious objectors and men of poor character cried,” striker Dorsett later said. “He told us to sit in silence for a while and pull ourselves together.”

“I did an interview at the start of the season,” recalled Gunners defender George Male, “where I suggested we were some way off winning the league. The manager George Allison wasn’t best pleased. He pulled me into his office and told me not to be so defeatist. But I just couldn’t see how the team was good for much more, to be honest.”

Legends of the ’30s David Jack and Alex James were gone, and Coventry’s Leslie Jones was the club’s only signing of note. “I didn’t hold out any chance for us, not without Alex James in midfield,” battle-worn striker Ted Drake explained. “To my mind, the quality of player just wasn’t there.”

Arsenal started the season well, hammering Wolves 5-0 in September and scoring 12 goals in their first three games. But just two wins in 12 followed, leading former Gunner Charlie Buchan to write in the Daily Mail: “Their decline is one of the surprise features of an amazing season, and one that is most unwelcome. The game cannot afford to have a poor Arsenal because there is no other team capable of supplanting them.”

As if to confirm Arsenal’s fall from grace, Drake’s injuries multiplied. He was hospitalised in April after being knocked out at Brentford. “Drake has been so often in the Royal Northern Hospital that he almost needs a permanent bed there to use whenever necessary,” said Allison.

Booed following a home defeat by Brentford, the normally avuncular Allison – who had praised the league’s surprise pacesetters (beating the Gunners home and away) as “worthy title contenders” – indulged in a few mind games, making enquiries for Bees forwards Jack Holliday and Billy Scott. Rebuffing the approach, Brentford manager Curtis claimed Allison had “tried to unsettle us at a key stage of the season”.

The Gunners felt the pressure. Forward Cliff Bastin, already losing his hearing, wanted a break. “I needed to get away from the thought of football,” he recalled. “It tires the brain… I’m not thinking quite so quickly as I was 12 months ago. It’s not a question of losing interest in the game; it’s a matter of snap.” George Swindin remembered Allison giving him three days off to “go fishing in the middle of nowhere... the pressure of winning, as you live through it, can be enormous”.

Yet Arsenal clawed themselves back into the title race. The crunch match came at Deepdale against high-flying Preston North End. The Yorkshire Evening Post didn’t rate the Gunners’ chances: “Arsenal experienced such a bad Easter, and their forwards are so out of form, that it seems certain Preston will win and occupy top spot.”

Arsenal won 3-1 in the mud. The 40,000 who saw Arsenal’s title-deciding final match at home to Bolton watched their team win 5-0. The man of the moment was pint-sized forward Eddie Carr. He played only 12 times for the Gunners and a knee injury at the start of the following campaign ended his Highbury career, but the seven goals that he scored at the tail-end of 1937/38 proved to be instrumental in his side winning the league.

Upon hearing Wolves had lost – they’d kicked off 15 minutes before Arsenal – the players dropped to their knees and were carried off the pitch. It’d been a draining experience. Arsenal’s 52 points from 42 games was the joint-lowest total for league champions. Adjusting for a 38-match season and three points for a win, their tally today would have been 66 points – some 15 fewer than Leicester managed in 2015/16.

Praise was grudging. The Lancashire Evening Post said: “Arsenal found themselves once more in possession of the championship, not so much by virtue of their old mastery and arts as by the late-season failure of Wolves, whose football on the whole was far more worthy of the honour.” Dixie Dean, so gracious and prescient at the season’s start, huffed: “That’s why they’re called ‘Lucky Arsenal’.”

The Daily Mail was a little kinder. “They have not always played like champions. They owe their success mainly to their wonderful defensive power and ability to keep the other fellows out.” Boring, boring Arsenal, indeed.

‘Lucky Arsenal’ were at their most fortunate in facing Double-chasing Preston a fortnight before the FA Cup final. Preston’s George Mutch admitted: “We were tense and rigid for that Arsenal match. It’s no excuse, but the FA Cup final was very much on our minds.”

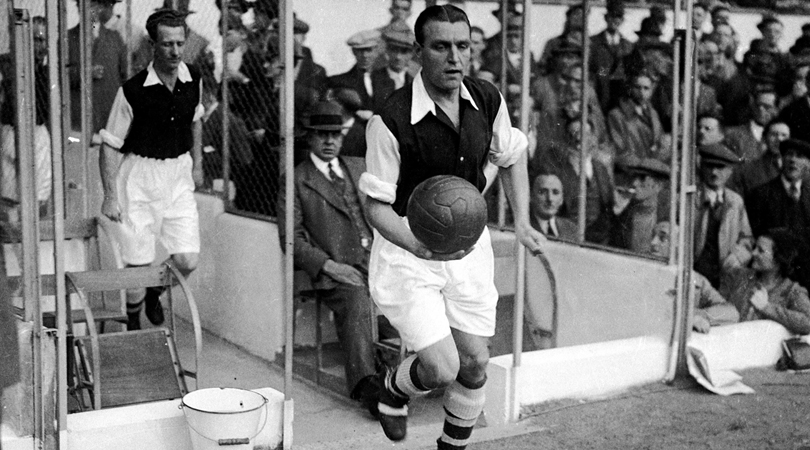

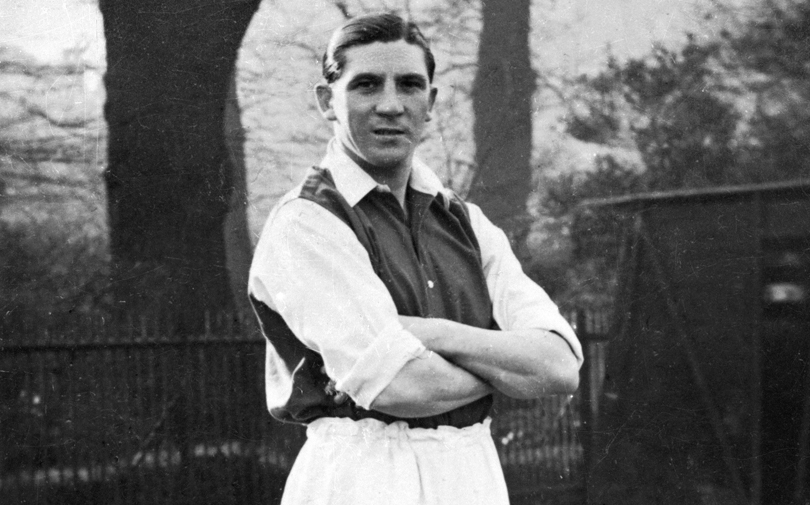

North End’s aesthetically pleasing passing game drew plaudits from many – even Bill Shankly, Preston’s ever-confident right-half. “Aye, we’re the best side on the eye, no question,” insisted Shanks. “But playing attractively is no good if you don’t win anything to show for it.”

Shankly, who had scored his first Preston goal in a 2-2 draw at Anfield in February, raged at his team-mates after the Arsenal defeat, insisting they “had to make sure we beat Huddersfield in the cup final to make up for it”. In the previous season’s final, they’d lost to Sunderland, with Shankly growling that North End’s long-sleeved shirts had drained them throughout the match.

Not in 1938, though: Shankly insisted his team wear short sleeves. It was also the first televised FA Cup final. The 93,000-strong Wembley crowd outnumbered British TV owners 10 to 1, but that didn’t stop the Daily Herald from running the headline: “The day is not far off when you may be able to watch your favourite football team from your fireside.” Spectacle was thin on the ground, however.

At 0-0, deep into extra time, commentator Thomas Woodrooffe uttered the infamous phrase: “If there’s a goal scored now, I’ll eat my hat.” On cue, Huddersfield’s Alf Young brought down George Mutch in the area, and Mutch stepped up to thunder home the penalty (after Shankly had declined the opportunity). Shankly later insisted his team won “because there were seven Scots on the team”.

Forward Bud Maxwell explained: “That final was a form of redemption for all of us. The previous year, we’d had our hearts broken. Now, I felt fulfilled.” But he was less convinced about television’s potential, claiming: “It won’t take off, believe me. Football is about the live event in fresh air. Who wants to laze around in a chair and watch football on a screen?”

Manchester City, who had won the title in 1936/37, seemed to have it made at the start of the new season. With rivals Manchester United relegated to Division Two, and City boasting such luminaries as goalkeeper Frank Swift, winger Ernie Toseland and the high-scoring trio of Eric Brook, Alec Herd and Peter Doherty, manager Wilf Wild insisted: “We can retain our title. It will be difficult, of course, but I’m confident that we can do just that.”

However, things went horribly wrong. Their forwards were as prolific as ever, with City banging in a division-high 80 goals in 42 games, but their porous backline let in 77.

The men from Maine Road routed several opponents at home. A good Charlton side were beaten 5-3; West Brom were battered 7-1. The problem was that City won only twice on their travels. One of those victories was a 7-1 win at Derby (whom they had also defeated 6-1 at home). After 17 games City were 10th, but in the new year they embarked on a run of seven defeats and two draws in nine games. Failing to recover their momentum and with only a fortnight of the season left, the reigning champions stared relegation in the face.

Nine other clubs battled the drop in the tightest relegation battle ever. Hot favourites to go down were Grimsby, whose chairman George Pearce took his players to visit a local soothsayer. The psychic informed the Mariners they’d stay up (although Pearce later admitted he had paid her double to deliver the positive news to his boys). Portsmouth, meanwhile, altered their training to include a daily dawn swim in the Solent. “It is a massive shock to the body,” admitted one unnamed Pompey star, “but we are of the feeling that something is needed to shock us out of our lethargy.”

The novel approaches worked: Grimsby and Portsmouth escaped the drop. But despite beating Leeds 6-2 in their penultimate game to climb to 16th, Manchester City were relegated along with West Brom thanks to a 1-0 defeat at Huddersfield on the final day of the season. City became the only champions to go down the next season and the only side relegated with a positive goal difference.

“The use of the word ‘staggering’ may be justified from different angles,” was the view on City’s demise from a bewildered Observer. The bottom of the table was ludicrously tight: just five points separated City from 10th-place Chelsea, and the gap between City and title winners Arsenal – 16 points – means the final table remains the joint-tightest on record.

City manager Wild remained in his post at Maine Road, having achieved, in the Guardian’s words, “the most Cityish act in City’s history”.

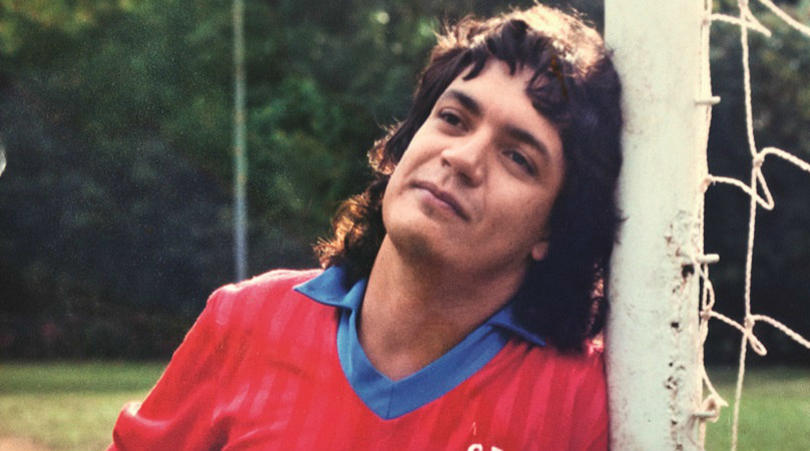

The hottest striker in 1937/38 was Everton’s Tommy Lawton, who netted 28 times. Yet the imposing centre-forward had the hump for the majority of the campaign, and his ire was directed at club secretary Theo Kelly.

“I couldn’t stand the man,” Lawton later recalled. “I’d regularly go and knock on his door and ask for a transfer, just to annoy him.” Lawton claimed he and Kelly didn’t talk “from around February 1938 onwards”, and for a while he stopped celebrating goals when he scored.

“To my mind, he knew nothing about football,” ranted Lawton. “Whenever I went to see him, he’d always send me back out of his office because I didn’t knock, and his message was the same. He’d say: ‘What you’re going to do, Lawton, is train today, and tomorrow, and the day after that, and the day after that. You’re going nowhere, Lawton.’ And that was how players were treated in those days. We were slaves.”

Vocal with the press, Lawton regularly informed local journalists of his stand-offs with Kelly. One Liverpool Echo headline in early 1938 ran: “Lawton And Kelly At Loggerheads. Yet Again.”

Whatever his grievances, Lawton successfully regained his composure to score the goals that propelled Everton to the league title in 1938/39 – and with Theo Kelly still at the club.

Meanwhile, perhaps prompted by the sight of Manchester City defenders having a set-to in the midst of another cataclysmic defensive display (the entire backline was fined by manager Wild after jostling and “using foul language towards one another” at the end of a 4-1 shellacking by Everton), Bishop of Manchester William Temple railed at “the coarse language and behaviour of footballers during the course of this season” in an open letter to The Times. He added: “They set a dreadful example to all those attending.”

Also subjected to criticism by the church was Britain’s football pools. The Baptist Union condemned the “phenomenal growth” of the pools industry, which it declared “injurious to moral sense and healthy sport”. The Union found unlikely allies in the Butcher’s Guild (a Worthing butcher informed the National Chamber of Trade’s conference that female customers were “buying cheap foreign meat to save money for the pools”) and the National Federation of SubPostmasters, who petitioned the government for a hefty pay rise given that some sub offices were handling upwards of 7,000 coupons weekly. Temple added in his Times letter: “Gambling, swearing, fighting…football needs to get its house in order.”

In a suitably crazy end to the season, Aston Villa took part in a tour of Nazi Germany. The first match saw an England side including Villa striker Frank Broome play Germany in the Olympiastadion, winning 6-3. Controversially, and under Foreign Office orders, the Three Lions performed a Nazi salute before the game.

A day later, Villa played in the same ground against another German XI, and due to the delicate political situation between Britain and Germany, they were told to salute as well. This time the players refused, and were hammered in the local press after winning the game 3-2.

In a third match in Stuttgart, Villa players complied with the diplomatic niceties. Sort of. According to Villa’s Eric Houghton: “We went to the centre of the field and gave them the two-fingered salute. They cheered like mad. They didn’t know what the two fingers meant.”

It had been that kind of season.

This feature originally appeared in the March 2016 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe!

Jon Spurling is a history and politics teacher in his day job, but has written articles and interviewed footballers for numerous publications at home and abroad over the last 25 years. He is a long-time contributor to FourFourTwo and has authored seven books, including the best-selling Highbury: The Story of Arsenal in N5, and Get It On: How The '70s Rocked Football was published in March 2022.