What if David Beckham had signed for Barcelona in 2003?

The former England captain was nearly a Camp Nou star - but this wasn't just a commercial move but one that could have changed the course of Barca's trajectory

By 2003, the relationship between Manchester United's David Beckham and manager Sir Alex Ferguson had passed its point of fracture.

Long before a flying boot had struck Beckham above the eye following a 2-0 defeat to Arsenal at Old Trafford in February of that year, Ferguson had been harbouring doubts about his midfielder’s attitude.

He wasn’t necessarily wrong and the anecdotes of the time hint at wavering focus. Such as the incident at Filbert Street, when Beckham refused to remove a hat during a team-meeting, ostensibly to protect the unveiling of a new haircut. Or how, unilaterally, he chose to miss training to remain with his unwell, infant son, causing a furious Ferguson to drop him ahead of a game against Leeds United.

They’re incidents with different interpretations. Beckham was a young father and still a young man, he was also becoming famous in a way almost unprecedented for a footballer and, most likely, subject to a battery of external pressures. But whatever the cause, Ferguson interpreted that behaviour as part of a pattern and, ultimately, as a challenge to his authority.

The dressing-room incident after the game with Arsenal was a challenge too far. Ferguson accused Beckham of being responsible for a Sylvain Wiltord goal. Beckham swore at him in response. Ferguson then took aim at a loose boot on the dressing-room floor and the two would end up having to be separated by the other players.

The day after, Ferguson did attempt a reconciliation. He called Beckham into his office to evaluate his performance and to explain why he had been so critical. The player was less than receptive. In fact, according to Ferguson’s autobiography, Beckham wouldn’t even engage in a conversation.

And that was the end; that was the moment at which Ferguson instructed his board to find a buyer.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Of course, the rest is history. Beckham would move to Real Madrid and continue his ascension into the game’s commercial stratosphere. Whether he was a footballing success in Spain is another issue, but he suited the environment and the environment suited him. Florentino Perez couldn’t have conceived a more ideal character for his Galactico circus.

For a detailed retelling of that episode and an insight into what instructed Perez’s interest and the mechanics of the deal, John Carlin’s White Angels provides a superb account.

The asterisk, though, is that Beckham might have been a Barcelona player. While the mood was souring in Manchester, a 40-year-old Joan Laporta was seeking the Catalan club’s presidency. Europe’s elite had smelt Beckham’s availability and so, as part of his manifesto, Laporta had promised to sign the England captain should he win the members’ vote.

It was a familiar move in Spanish football politics. Notoriously, Perez had won his own election in 2000 partly by promising to meet Luis Figo’s release clause. It had helped him to unseat the incumbent Lorenzo Sanz and so, with such a precedent, Laporta’s Beckham promise could be interpreted as easy populism. It was common knowledge that Madrid held a long-standing interest and any Barcelona attempt to steal him away would have played well to the gallery.

Not that it was electorally decisive. Laporta’s trump card was not Beckham, but rather the patronage of Johan Cruyff. Sitting president Joan Gaspart had overseen a period of sharp decline, the club’s finances were a mess, and his resignation was forced in early 2003. In the three seasons following the turn of the Millennium, the club failed to finish higher than fourth in LaLiga. In 2003 itself, they languished in a lowly sixth place.

The context for was ideal. Particularly given Cruyff's simmering contempt for the departing president and the personal history between the two.

In 1996, Gaspart had been Josep Nunez’s vice-president and had himself delivered the news of Cruyff’s sacking. It was an ugly exit and a confrontation which nearly became physical. Popular opinion in Catalonia had concluded that Cruyff’s usefulness as manager had expired, but the manner of his departure and its lack of respect was an affront to the native culture.

The timing of a return couldn’t possibly have been better. Nor the optics. Prior to arriving as manager in 1988, Barcelona had won two league titles in 28 years. In the eight years Cruyff had spent at Camp Nou, he’d won the Primera Division four times. He’d also won three Spanish Cups, the European Cup and the Cup Winners’ Cup. He was both the natural antidote to Real’s advancement and the cure for Barcelona’s stylistic myopia.

Laporta would subsequently win power and, remaining true to his pledge to restore the DNA, would employ original Dream Team member Txiki Begiristain as his sporting director and Frank Rijkaard as his head-coach. Rijkaard was very much Cruyff’s recommendation. In spite of their acrimonious past and Rijkaard’s only club management role having been with Sparta Rotterdam, he was nevertheless chosen as Radomir Antic’s successor.

He was to be the disciple, the technical area avatar for Cruyff and his beliefs.

But even with the foundations in place, results didn’t immediately follow. In fact, the first half of the 2003-04 season was semi-disastrous. The 5-1 loss to Malaga at La Rosaleda was a deep blemish for the new regime to bear, but the low point was arguably a 3-0 defeat in January in Santander, which dropped Barcelona to 12th place.

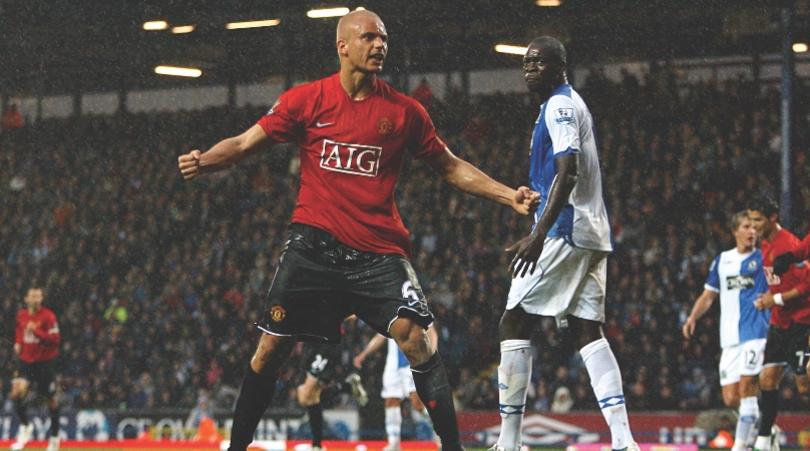

The recovery is a well-told story. Edgar Davids would arrive on loan in January and the team wouldn’t lose in the league again until May, eventually finishing second. The Dutchman was by no means solely responsible, but the attitude and tenaciousness he brought to Spain has often been credited with the setting of a new standard. Xavi Hernandez, in particular, has always spoken effusively of Davids’ effect.

So, happily ever after: Rijkaard would coach the side to two La Liga titles and a European Cup and, before his gentle style allowed egos to swell and standards to drop, he would help prepare the ground for Pep Guardiola, a fresher set of fertile ideas, and the club’s climb to its contemporary position.

But what of Beckham? Hindsight makes this a fascinating sub-plot, because although Laporta’s intention to sign him was instructed by something other than pure sporting values, Beckham would possibly have been a great obstruction to the club’s future. No doubt he would have proven a commercial coup and offered routes into lucrative markets, but accommodating a player of his profile would have come at an opportunity cost.

In a 2017 interview with Marca, Laporta revealed just how serious the interest was. Evidently, this was not a move made for the sake of cheap publicity and, given the chance, Barcelona would have followed through.

“It was between Beckham, Ronaldinho or [Thierry] Henry. United told us that they would sell him to us if we won the [presidential] election as we didn’t have the power at that time. But they used us and in the end he signed for Madrid. We met at Heathrow Airport and signed a document which said that they would sell him to us if we struck an agreement with the agent.

“However, we didn’t manage to do that. We went to Nice and stayed with him and he said he would think about it. We got fed up of waiting on an answer, so we signed Ronaldinho instead.”

It’s confusing, because Beckham was nobody’s idea of a Cruyffian player. He was talented and hard-working, but still mechanical and hardly associated with the soft-footed technique of La Masia lore. Nor was he particularly pliable or obviously suited to the multi-role style which would become Barcelona’s signature.

Today, he is falsely remembered as more icon than footballer; it’s unfair, he was a fine player who has the medals to prove it.

Nevertheless, his optimal role at Manchester United was on the right side of a midfield four and, prior to that point, any experimentation with that position had resulted in failure. His performance in the 1999 Champions League final, for instance, when suspensions to Paul Scholes and Roy Keane forced an impromptu central-midfield partnership with Nicky Butt, was deeply underwhelming. Beckham and Manchester United were clearly drained that night, exhausted and unbalanced by the challenges of a season contested across so many fronts, but Bayern Munich dominated the middle of the pitch and Beckham’s influence in open play was deeply limited.

Cruyff admired Beckham. He liked him as a person and as a professional and, in his book, talks fondly of how welcoming he and Eric Cantona were when Jordi, his son, moved to Manchester United. Tellingly perhaps, that is the only mention he receives. There is no suggestion that he saw in Beckham any of the traits he celebrated in other players.

It’s interesting, also, that, in the same summer that Beckham moved to Madrid, Barcelona chose to sign Ricardo Quaresma, who – as a right-sided midfielder – was an entirely different proposition. Flash and unreliable, full of extravagance and contradictions; Quaresma was built from something else entirely and neither would ever have ever have appeared on the same shortlist.

Under Rijkaard, Barcelona began the season in a 4-2-3-1 shape, with Quaresma starting on the right. Gerard Lopez and Xavi played as the deepest midfielders, Javier Saviola as the centre-forward, and Luis Enrique and the Portuguese either side of Ronaldinho in a No.10 role. By the turn of the year, they had – via a dalliance with three centre-halves – pivoted to a very Dutch, very Cruyffian 4-3-3. One could argue that the initial shape was determined by the players they ultimately did sign over the summer, but it’s realistic to assume that 4-3-3 had always been the vague intention.

Maybe Beckham could have adapted, but there’s little basis for believing so. He was always at his most impactful from the outside of a full-back, and his presence in that team would surely have opposed the flexibility that Cruyff – and Rijkaard – would have viewed as necessity.

He would admittedly have provided stable width, another imperative which was being embraced, but Patrick Kluivert’s peak had passed (he would be sold to Newcastle at the end of the season) and so in the absence of a traditional centre-forward, Barcelona lacked the focal point to exploit Beckham’s one, obviously outstanding attribute.

The irony is that Beckham often played centrally for Madrid. In fact, in his first Clasico appearance against Barcelona (at Camp Nou in December 2003), he started in a midfield pair with Ivan Helguera and within the confines of a familiar 4-4-2. Real won the game 2-1, but – while slightly tenuous – it’s possible to see a correlation between how often he operated away from his best position and how little he actually won during four years in Spain.

Perez’s Disneyland psychosis was at its deepest during that era and Beckham was by no means the only positional anomaly, but the midfield became a typical weakness. In 2003-04, Madrid got only as far as a Champions League quarter-final, but then suffered elimination at the Round of 16 stage in each of the next three seasons. History shows that when they faced the very best sides in Europe – including Barcelona – the many flaws of their recruitment policy were exposed. It’s also not a coincidence that they would have to wait until Beckham’s final season, in 2007, to win La Liga again, but which time Emerson and Mahamadou Diarra had been signed and some deference to tactical responsibility had been allowed.

But then, the aims of the two clubs were very different: what made Beckham a must-have item for Madrid is exactly why Barcelona’s interest remains so baffling.

It remains a seductive "What if?". Although difficult to comprehend, it’s tempting to imagine what might have happened had the transfer gone through. Barcelona’s financial position at the time was insecure, meaning that Laporta’s ‘Beckham or Ronaldinho’ scenario is entirely credible. Had the Brazilian not joined and moved instead to Manchester United, Barcelona’s modern history could well be very different. It’s a true sliding doors moment: there would likely have been no Champions League win 2006, no irresistible momentum, and no capturing of the world’s footballing affections in the years - and decade - which followed.

Ronaldinho’s career was not what it should have been. And, by today’s standards, his exuberance and flair aren’t quite so dazzling. But he was a uniquely entertaining player and, although his peak was short-lived, he remains an indelible part of Barcelona’s identity. Perhaps not quite as much now, but certainly at the time.

Xavi Hernandez and Anders Iniesta would still have been at the club, Pep Guardiola and Leo Messi might still have been on the horizon, but the butterfly effect of what would have been an incomprehensible error can’t be underestimated.

Beckham instead of Ronaldinho? It’s unimaginable now. Even the player’s fabled commercial worth might have looked different – or at least out of place. Beckham was – and remains – a tremendously valuable property and truly an icon of the sport. But did he belong at Barcelona? He was an emblem of footballing capitalism, after all, and had a type of allure which was incongruous with their values.

Conversely, had there ever been a more perfect match than 2003’s Beckham and Perez’s Real Madrid? They were destined to be together. Specifically at that moment in time, in that age of the game.

Of course, he wasn’t really the right player for Madrid either. He glittered enough to satisfy Perez’s starlust and he was good enough to fit the surroundings, but his signing did a disservice to the many, many gifted players already at the club. Zidane, Figo, Ronaldo and Raul needed nuts and bolts, Perez bought them another tin of varnish and a further fist of glitter. Nevertheless, with no real native culture, his transfer only really represented a misuse of funds and – over time – just became further proof of that project’s naivety.

At Barcelona, however, where lineage has always had the greater premium, it would have been the kind of self-inflicted ideological mistake which would still be echoing in the present day.

Even now, nearly seventeen years later, it remains almost impossible to rationalise.

While you’re here, why not take advantage of our brilliant subscribers’ offer? Get the game’s greatest stories and best journalism direct to your door for only £12.25 every three months – less than £3.80 per issue – and you’ll also receive bookazines worth £29.97!

NOW READ...

REAL MADRID Vinicius Jr reveals the Real Madrid player who has helped him most so far – and they’re not Brazilian

QUIZ Can you name the top scorers in Europe's top five leagues this season?

GUIDE Premier League live stream best VPN: how to watch every game from anywhere in the world

Seb Stafford-Bloor is a football writer at Tifo Football and member of the Football Writers' Association. He was formerly a regularly columnist for the FourFourTwo website, covering all aspects of the game, including tactical analysis, reaction pieces, longer-term trends and critiquing the increasingly shady business of football's financial side and authorities' decision-making.