The death of the disciplinarian? Why coaches like Jose Mourinho are losing their touch

The Portuguese’s public lashings don’t seem to be having the desired effects upon his players – so are the days gone for iron fists?

It’s been a tough week for tough love. On Saturday, two days after Jose Mourinho questioned his players’ character, name-checking four of them and saying that today’s young footballers fit the description of "spoilt kids", his side limped lamely to a goalless draw at home to the league’s most out-of-form side.

If he’d intended his words of disparagement to be construed as motivation, his plan had misfired badly – and not for the first time, either. No hugging, no learning.

A day before Mourinho had aired grievances about his squad, the Republic of Ireland’s FA bid goodbye to the managerial duo of Martin O’Neill and Roy Keane, a bad cop-worse cop pairing whose methods had been causing more harm than good for some time. Both have reputations as old-school motivators, but a blueprint that might once have roused the troops instead led to a fractious atmosphere, laboured football and spiralling morale.

Improper football men

That these two episodes blew up on consecutive days may be little more than chance, but it does seem to speak to a certain change in culture that appears to be creeping through English football.

Many of the managers who have built their careers on a bedrock of stern-faced severity have recently found themselves struggling badly, slipping towards anonymity or simply out of work altogether. Sam Allardyce, David Moyes, Tony Pulis and Mark Hughes – as well as Mourinho himself – can all be placed in this broad bracket. All reached their personal pinnacles about 10 to 15 years ago; none look likely to return there any time soon.

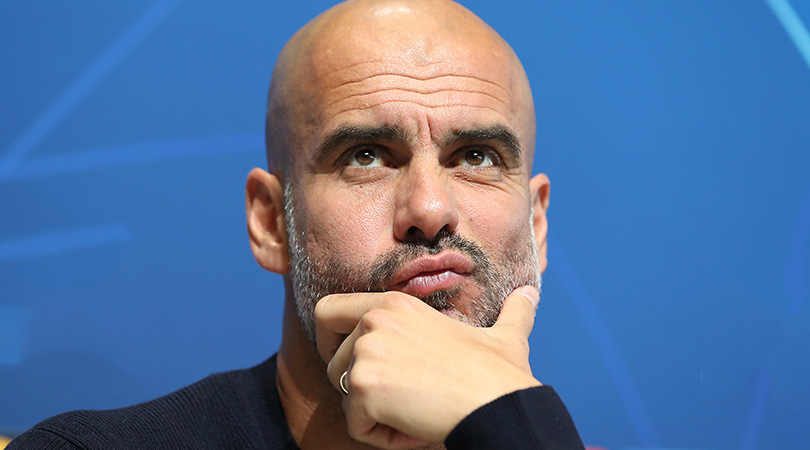

At the top of the Premier League table, meanwhile, it’s all about the smiles. Pep Guardiola is a famously paternal presence to his players, and one who sees no harm in them having fun. “More than just winning things,” Xavi said of his time at Barcelona, “my memories from that era are of how much I enjoyed it.”

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

City, who will surely waltz to another league title this season, certainly appear to be enjoying themselves too.

Jurgen Klopp and Mauricio Pochettino, in second and third place respectively, have revitalised their clubs from top to bottom and enthused their fan bases with electrifying football.

When it comes to their players, neither is shy of delivering a grinning eulogy or two. Both make a habit of dishing out the bear-hugs at the final whistle, as paragons of positivity. The famously superstitious Pochettino is so fearful of “negative energy” that he keeps a bowl of lemons in his office to counteract it.

Maurizio Sarri, hot on Spurs’ heels in fourth, is not so much of a smiler but no less an advocate of affirmative energy. After Chelsea played Liverpool last month, he told of an exchange between him and his counterpart: “I saw Klopp looking at me with the game going on. I asked, ‘Why are you smiling?’ He said, ‘Aren't you having fun?’ 'I said: ‘So much!’ and he said, ‘Me too!’

Top me up

That sort of touchline tete-a-tete may be hard for rival fans to take – and certainly those in the broadcasters’ boardrooms would prefer superstar coaches to be at each other’s throats – but the results speak for themselves: Guardiola, Klopp and Pochettino have their clubs playing some of the best and most effective football in their history. There’s little to suggest that Sarri won’t do the same.

That the men share a similar glass-half-full approach to the job, and have risen to the top of the sport in almost perfect unison, is surely more than simple coincidence.

Of the Premier League’s other overachievers, Eddie Howe, Chris Hughton and David Wagner are similarly affable types who have little interest in the siege-mentality MO that once predominated. And the great footballing achievement of modern times – maybe even of all time – was orchestrated by Claudio Ranieri, a manager whose defining trait was less tactical diligence and tub-thumping impetus, more an all-consuming air of infectious, upbeat warmth.

At which point it’s worth saying that much of these characterisations are grossly oversimplified: it’s not as if Pep and the gang are saucer-eyed hippies incapable of enforcing any sort of discipline. Likewise, Jose Mourinho has been known to enjoy himself every now and then; even crack the odd joke.

O’Neill has a certain sense of humour himself and neither is Keane a man devoid of compassion. As he wrote of his time at Sunderland: “Staff would come to me asking, say, for time off because of marital difficulties, or problems with their children. I think that was one of my strengths, that I had a kindness to me.”

Teacups

But as much as it’s true that all these managers are not simply either lovers or fighters, it’s also the case that some lean more towards the latter than others. Keane, after all, is the same man who recounted the story of Brian Clough punching him in the face as punishment for an underhit backpass. “It was the best thing he ever did for me,” he said. “It's good to get angry.”

That story is one that has passed into legend, speaking as it does to a bygone era where men were men, teacups were made to be thrown, and to be bellowed at in front of one’s team-mates was a sacred rite of passage. And for the two men Keane played the majority of his career under, such methods bore untold fruit.

Which is all well and good, but the mistake comes with the idea that the methods of the past will work straightforwardly in the present. The stories emerging from the Ireland camp of Keane stalking the treatment rooms, accusing players of feigning injury and shirking their workload, suggests that his particular brand of criticism had long ceased to become constructive.

Likewise, Mourinho’s drill-sergeant act appears to have fared a lot better with the generation of players who had a living memory of football’s less gilded times – who may even have served their apprenticeships in the pre-Premier League era – and had seen first-hand just how fortunate they were to have come to the fore when they did.

These days, the Portuguese’s methods are more likely to cause toxicity: see how he alienated almost the entire Real Madrid dressing room; how he left Chelsea 16th after 16 games in 2015; how he now lashes out at his own Manchester United players almost bi-weekly.

Today’s young footballers have known their industry to be nothing other than one overspilling with money: a lifetime of millionairedom has probably been inevitable since their early teens. And no, they didn’t spend their youths sweeping the changing rooms and cleaning senior pros’ boots.

Tweet this

Football has changed – and the world has changed, too. In an era of celebrity footballers, 24-hour news and the brutal judgments circulated on social media, a player singled out for public criticism may take it to heart in a way their forerunners didn’t.

Whether you call it spoilt, sensitive or insecure is just semantics: the point is that young players today are different to those of the past. The challenge for their managers is not to change them back, but to change themselves in response.

And if the results are anything to go by, the coaches faring the best are the ones who recognise that encouragement and indulgence aren’t four-letter words. Or as Sarri puts it: “I’ve come to realise that there’s a child in every footballer. That’s where the fun part is. Tactical rigour is important, but we must never lose sight of the game and making sure the child inside is enjoying himself.”

It’s a message to which Mourinho, Keane and the rest would do well to heed. Because the story of middle-aged men railing against the moral failings of today’s youth is a story approximately as old as civilisation itself. And – spoiler alert – it’s never the old guys who have the last laugh.