Don't read all about it: Mundanity, meddling and muting in football journalism

Raheem Sterling's arrival in Manchester highlighted a worrying trend of mind-numbing footballer interaction, writes Nick Harper - but the landscape is changing on another level...

Tuesday July 14 was a very black day for British football.

You may not remember the day as being much other than just another 24-hour stretch without meaningful football, but in the future we may look back on it as being a turning point in the history of the game. Certainly a turning point in the history of football journalism. Let us rewind to the day in question to refresh your memory.

On Tuesday July 14, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft performed a close fly-by of Pluto, the first spacecraft to do so. Iran agreed to long-term limits of its nuclear program in exchange for sanctions relief. And Raheem Sterling was officially unveiled as a Manchester City player. But not through the traditional channels.

Once upon a time, not all that long ago, the shots of a player wearing the new shirt of his new club and holding a scarf awkwardly above his head would have been splashed across the back page of whichever lucky tabloid managed to secure the exclusive. This time, following a worrying trend of recent years, Sterling was unveiled in an exclusive interview with Man City TV.

Raheem and the elephant

At a fat £49 million and with the slings and arrows raining down on young Raheem, the move to Manchester City threw up numerous questions – from his loyalty to Liverpool, Brendan Rodgers and the club’s fans, to the death threats, the mystery illnesses and Jamie Carragher ‘Knobgate'. There were many questions but, over the course of the official eight-minute video, none of them were asked.

They quickly moved on – to talk about how he loves playing FIFA with the boys, and how his mum says he looks good in blue

Sat on a chair at Manchester City’s expensive, expansive 25th-century training facility, the interviewer asked him if he’d always wanted to be a footballer, if the move had made his mum happy and if he was looking forward to going on his new club’s tour of Australia. When the elephant in the room grew too large, four-and-a-half minutes in, the interviewer asked about the things people who didn’t know Raheem had been writing about him, and wondered if it had been difficult.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Raheem replied that he didn’t read the newspapers and they quickly moved on – to talk about how he loves playing FIFA with the boys, and how his mum says he looks good in blue. And so on and so forth.

Of course, this is understandable. Manchester City closing ranks and choosing to unveil their new signing via the safety of their in-house media team makes complete sense. They could control the questions, edit the answers and make sure Sterling didn’t have to sweat over any of the real questions we all wanted answers to. Just as importantly, by running it on the official Manchester City website, they enjoyed a spike in traffic which, in turn, will have given additional exposure to their stable of 17 heavyweight sponsors.

This is the modern world and these are the modern ways, particularly at the very sharpest end of the Premier League. However, down in Wiltshire and two leagues below, another news story was clearing its throat on Tuesday July 14. And it was an altogether more troubling tale.

Swindon, Fanzai, folly

Back in January 2014, Swindon Town banned the local daily newspaper, the Swindon Advertiser, from attending press conferences at the club. All its media requests and questions were ignored.

The Advertiser claimed that the chairman justified the move by saying he already got all the coverage he wanted via other media outlets

The Advertiser claimed the chairman justified the move by saying he already got all the coverage he wanted via other media outlets. On July 14, 2015, the headline above announced that the chairman had extended the ban to all media and that apart from the obligatory post-match press conference with the manager, all media activity would be conducted via a mobile app, Fanzai.

“They just want to control media output for the club and don’t want journalists asking questions,” explained Advertiser editor Gary Lawrence. “All interviews are conducted by the PR team and journalists aren’t made welcome.”

Of course this is nothing new. Sir Alex Ferguson remains the most high-profile example, waging a one-man war with the BBC that saw him refusing to talk to the corporation for seven years after they aired a documentary that made allegations about his then-agent son. And where Fergie led, others have followed.

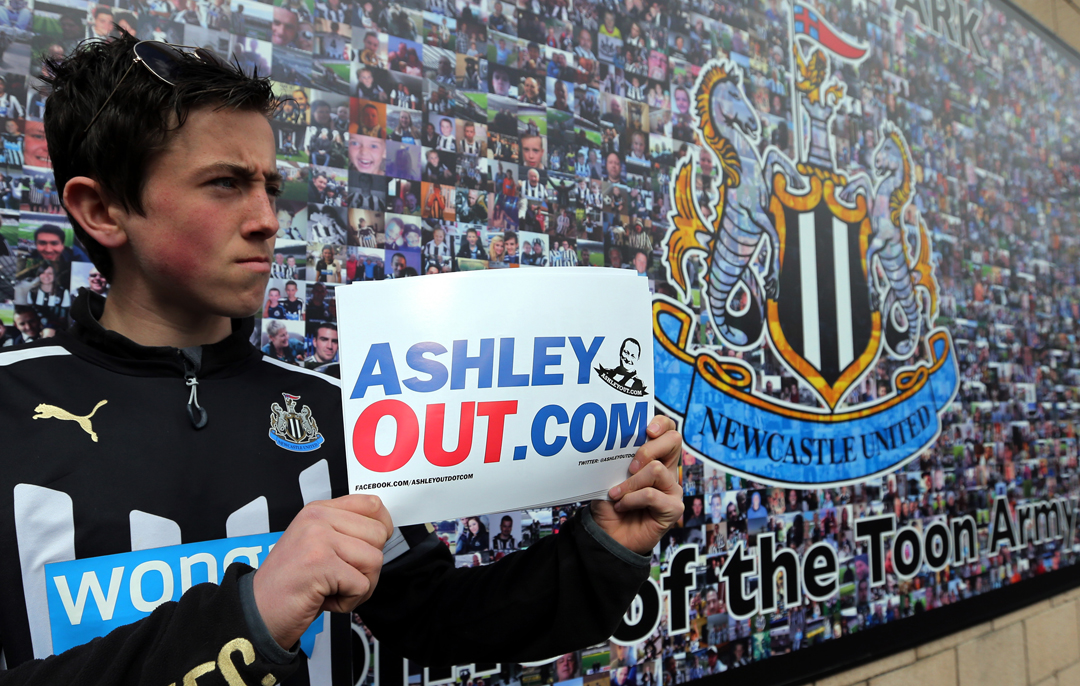

In recent seasons Newcastle United have banned the city’s three newspapers for daring to take the fans’ side in a protest against owner Mike Ashley. The recent unveiling of Steve McClaren as the new manager was a carefully controlled affair – everyone was banned from attending except Newcastle United’s two preferred media partners, Sky Sports and the Daily Mirror.

Port Vale chairman Norman Smurthwaite banned the local paper’s reporter and photographer after taking umbrage at a report, then demanded £10,000 a year for access to the press box and press conferences. Crawley Town banned a reporter from the Crawley News because the club disliked two headlines.

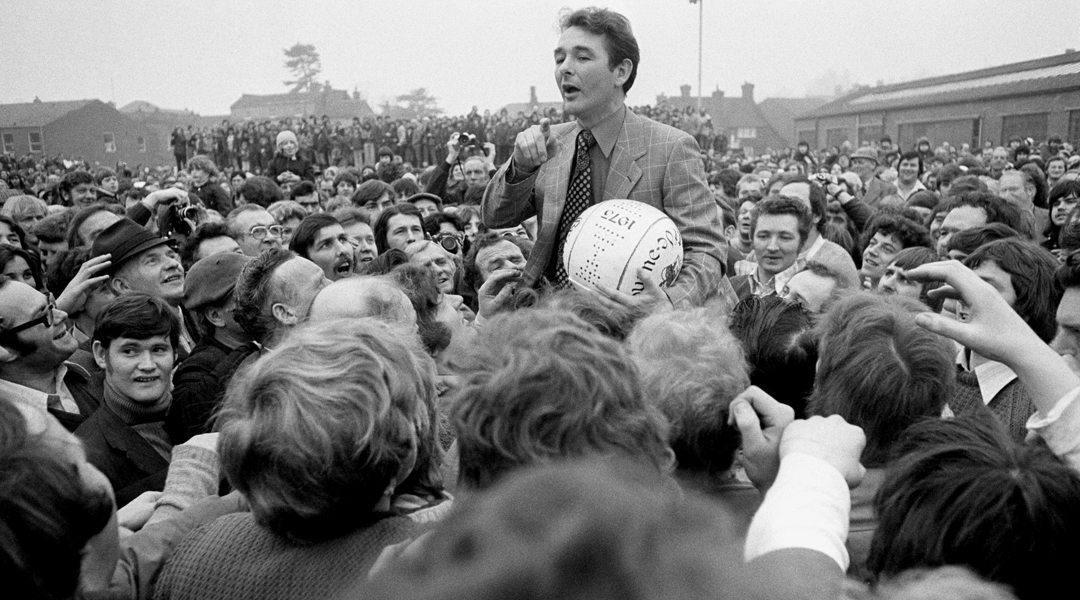

Southampton banned photographers in an attempt to make media outlets buy its own official images, then prevented journalists from the Southern Daily Echo from interviewing fans outside the stadium. And at Nottingham Forest, where Brian Clough once allowed local journos almost unrestricted access in the more liberated 1970s and ’80s, journalists have been banned for attending games but not writing up a match report, while daily access to the players for the local paper and radio station has been denied.

Times are changing. We have a media team of our own who are fully focused on keeping fans updated

“Times are changing,” said Forest’s media and communications manager, Ben White, at the time. “We have a media team of our own who are fully focused on keeping fans updated.”

The in-house media team is a relatively modern phenomena. Once clubs employed a pleasant press officer to deal with requests for information and interviews. Nowadays almost every club requires a dedicated department of sharp-suit to be “fully focused on keeping the fans updated”. But given these people are on the payroll, is that healthy? And are those updates even news?

"You might as well not bother"

"News is what somebody does not want you to print. All the rest is advertising."

We criticise when things go badly and we hold them to account for bad decisions

George Orwell said that, or so the theory goes (the quote has been attributed to several other sources), and while he wasn’t talking specifically about football reporting, it fits the bill here very nicely.

“Newspaper journalists have always been irritating to football clubs because we are not easy to control,” says the Daily Telegraph’s North East correspondent Luke Edwards. “We often report things clubs don't want in the public domain, as well as the things they do, we criticise when things go badly and we hold them to account for bad decisions.”

Edwards and the Daily and Sunday Telegraph have been banned by Newcastle for reporting that Ashley was willing to listen to offers for the club, a story they denied as being “wholly inaccurate and written with the intention of unsettling the club, players and its supporters”. No legal action was ever taken.

Edwards remains unrepentant. “Significantly, we do what we do for free and that annoys people in football,” he says. “Media companies make money from their football coverage and clubs no longer believe they need newspapers' coverage to sell their product. They are right, to an extent, but more people still read about football in newspapers than watch it on television.”

Of course, newspapers still get access to footballers, but the relationship has changed dramatically. “Back in my day, you’d see a journalist in a bar, he’d buy you a beer, you’d have a moan, he’d have a moan and you knew it would all be fine,” said Steve McManaman in a recent interview with FHM. There was, he said, a mutual trust that if what had been said was on the record, it would not be spun or twisted out of context.

Nowadays, however, moans McManaman: “The chase for the headline’s got to the point where you’d pick up the paper the next day and it’s completely not what you said. The British press always want action; they want a player dropped, they want a manager sacked.”

Back in my day, you’d see a journalist in a bar, you’d have a moan, and you knew it would all be fine

The access media enjoy nowadays is often through the sponsors, who pay a player to promote their boots or their computer game. Generally speaking, for any of them to be granted time with the player they must first agree to offer the agent and club full question approval. Anything that may cause any kind of controversy will come back with a red line through it, anything guaranteed to elicit a bland but safe response will usually get through.

When the interview takes place, the player’s agent will usually sit in to guarantee the journalist doesn’t veer from the list of approved questions and safe subjects.

And when the interview is in the bag, full layout and final copy approval are often agreed to, to make sure nothing vaguely controversial or indeed anything interesting slips through the net and makes it onto the page. George Orwell would call it advertising. Steve McManaman called it a waste of time.

“Interviews you read today are so mundane and so boring,” he says. “You might as well not bother interviewing players at all anymore.” That day might not be very far away.

Everything is awesome

Sadly, football clubs want to live in a world where, like The Lego Movie, everything is awesome

The Swindon ban appears to represent the most extreme, totalitarian approach to media relations yet. “What Swindon will produce ahead of its matches in 2015/16 – as it conducts pre-game previews solely on its own website – will be little more than promotional bluster,” warns Sam Morshead, head of sport at the website Total Swindon. “Movie trailers minus the CGI or dramatic voiceovers. Articles so chemically sterile they ought to be used for cleaning urinals. No real questions, no real answers, no real accountability.”

It’s a warning echoed by the Telegraph’s Luke Edwards. “Football has become about more than money,” he says. “It has become about brand management and the inevitable bi-product of big business, public relations. Sadly, football clubs want to live in a world where, like The Lego Movie, everything is awesome. When they lose a game they only want their fans and sponsors to read about the positives and how they will be working hard to put things right. In other words, the sort of stuff you get on an official club website.”

Do football fans want Pravda or independent reporting? Important Luke Edwards piece on Newcastle and the war on truth August 1, 2015

A free press, he believes, is a vital cornerstone of a free and democratic society. “But we are starting to see a challenge to that in football that should alarm supporters,” he says.

“It is difficult to play the sympathy card, journalists are not universally liked or respected, but fans should ask themselves this: do you want to only know about what a football club wants you to know, or do you want to read things that they would prefer you didn't?”

Fanzai deals only with the things its clients (30 players and counting) and Swindon want you to read and nothing at all they don’t. They control the content and there is no interaction with consumers.

It’s great if you want shot after shot of John Terry on a beach or on the golf course or on the training pitch with the boys. Or if you want to check out Gabriel Agbonlahor’s new sneakers or injured leg. Or keep up to speed with Swindon's junior team results. But for any real insight or depth, or the type of traditional investigative journalism our newspapers very often get right, it may well make you feel sick.

Fanzai was set up with applaudable intentions – to provide a social media platform offering football content from players and clubs that's free of the type of abuse found on platforms such as Twitter and YouTube. The trouble is, right now, all it achieves is to build an even bigger barrier between its footballers and their followers. They post, you read and we all move on. It’s instant but instantly disposable.

Fans lose

The bigger worry is what if this really is The Future. What if, soon, having seen the bubble in which JT and Swindon can exist without being bothered by slobbering journalists, other players and clubs sign up? What if even more of them retreat behind this protective social networking shield, drip-feeding only what they want you to read? A terrifying thought, but that is the plan.

What if even more of them retreat behind this protective social networking shield, drip-feeding only what they want you to read?

“In five years’ time the dream would be to have every major club in the UK and across Europe – and the players – using Fanzai as one of their social media channels,” say its founder, Ben Keogh, whose ambition and eye for the big chance has to be admired.

But while it may sound like a dream for Fanzai, for the players and their agents and, providing they find ways to monetise it all, for the football clubs themselves, for everyone else it may well be the stuff of nightmares.