How the 2000s saved El Clasico – and made Barcelona vs Real Madrid bigger than ever before

Barcelona and Real Madrid despise one another - but it took a symbiotic relationship in the noughties to make their rivalry the biggest in world football. FFT delves into the blossoming of a bitter romance

This feature first appeared in the Summer 2020 issue of FourFourTwo magazine.

Duality was a cornerstone of late-Victorian literature’s most enduring characters.

The same yet different, each was inexorably defined by, and drawn to, the other. There was mistrust, hatred, but also a fascination with their opposite. Holmes vs Moriarty; Jekyll vs Hyde; Dracula vs Van Helsing; Dorian Gray vs his portrait – the more that these conflicted souls understood about their enemy, the more they learned about themselves.

Real Madrid and Barcelona were always destined to hate one another. They were born just a few years after those duality tales, but the teams of the establishment and of militant separatists could never be friends – not with such philosophical, political and geographical differences, amid a brutal Spanish Civil War and right-wing dictatorship from 1936 to 1975. Yet that shared antipathy tied them together.

Going into the 2000s, El Clasico had already been Spain’s biggest football match for over half a century. By the decade’s end, however, in which they shared seven La Liga titles and four European Cups, it had exploded into the biggest game on the planet. Spanish football’s behemoths had made their league the world’s hottest competition and turned themselves into the most glamorous destinations for top talent. So: why the sudden interest?

Simple. On July 24, 2000, Luis Figo left Barça and joined Real Madrid. Nothing would be the same again.

Just ask that pig.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

"Of the 10 best players in the world, we've got five"

In 1998, Real Madrid had awoken from their slumber – but something within gnawed away. The club which had defined itself by European Cup glory, ever since winning the competition’s first five tournaments in the late 1950s, had finally ended a 32-year wait for la septima – the seventh – but Barcelona were just... sexier.

During the 1999/00 campaign, Los Blancos were well placed in the Champions League, sure, but they had finished 11 points behind Barcelona in the previous La Liga season and entered the new millennium in mid-table. Madridismo couldn’t take it.

Florentino Perez decided to run for the office of Real Madrid president. A short, puffy-faced civil engineer, he was the president of ACS: Spain’s third-largest construction company, with a €4 billion turnover. What Perez lacked in presence, he more than made up for in ideas or enchufes – the political and financial connections that greased wheels. He counted Jose Maria Aznar, the Spanish Prime Minister, as both a colleague and a friend.

By the time Perez submitted his candidacy on June 30, it would be a one-on-one race between the upstart and Lorenzo Sanz, who had just delivered two European Cups in three seasons. No one gave the engineer a prayer.

Yet Perez had his finger on the pulse of madridismo. How? Because he asked them. While preparing his bid, Perez commissioned a questionnaire which asked the club’s fans to name the player they wanted Real Madrid to buy above all others.

Luis Figo was the overwhelming winner. The winger would later lift that year’s Ballon d’Or, yet Barcelona were playing hardball over a new contract and he was annoyed by the impasse. The release clause stood at £38m: a potential world-record fee, but affordable. Just.

Perez offered a non-returnable £1.6m to Figo’s agent, Jose Veiga, for his client to sign a document saying that he would join Real Madrid if Perez won the election. Easy money, they thought – after all, Perez had absolutely no chance of winning.

Perez announced his mini-deal on July 6, the day his presidential rival gave away his daughter to Real Madrid’s full-back Michel Salgado. “Maybe he’ll announce he’s signed Claudia Schiffer next,” sneered a blasé Sanz at the wedding.

Figo denied everything – both in public and privately, to team-mates Pep Guardiola and Luis Enrique. Ten days later, Perez triumphed by a landslide. To cancel the deal, incoming Barcelona president Joan Gaspart would have to pay Real Madrid a £19m penalty clause, effectively to keep his own player. A furious Gaspart refused; Figo himself felt let down by the club. “They thought I was bluffing,” he told FourFourTwo later. “Maybe it wasn’t very, very clear, because it didn’t depend only on me.”

On July 24, a barely smiling Figo was unveiled at the Bernabeu. A club insider says Gaspart “went into shock... he couldn’t think rationally. He was destroyed by Madrid.”

Attention turned to October’s first Clasico of the season, in Barcelona. Stirred by a febrile Catalan press, the Camp Nou atmosphere was different: visceral, unapologetic hatred. There were angry banners everywhere. ‘Mercenary’. ‘Judas’. ‘Scum’. Thousands of fake bank notes emblazoned with Figo’s face were printed and thrown onto the pitch. He was visibly shocked and refused to take corners, though that didn’t stop the maelstrom of coins, lighters, whisky bottles and golf balls being chucked his way.

Unsurprisingly, Figo played dreadfully. With a pumped-up Carles Puyol his shadow for 90 minutes, Real Madrid lost 2-0.

“Physically and mentally, it is impossible to ignore 75,000 people shouting against you,” Figo later told FFT. “I was worried that some madman might lose his head.”

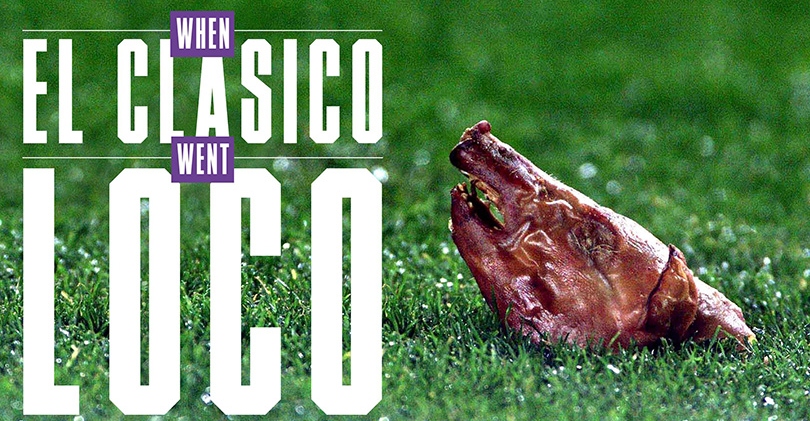

Two years later, a pig did. Water under the bridge? No chance. A cochinillo – a roasted suckling pig’s head – thrown onto the Camp Nou turf became El Clasico’s defining image. The match – a 0-0 draw – was suspended for 16 minutes, though Barça escaped sanction, their directors accusing Madrid photographers of a setup: “We don’t even eat it in Catalonia.” The world was captivated.

Perez had his superstar, but most of all, he had his reaction – and that was priceless.

Throw back to when Luis Figo returned to the Nou Camp with Real Madrid. They literally threw a pig's head at him. pic.twitter.com/EOIXflMWetApril 11, 2017

The notoriety that the Figo transfer gave to Perez was a drug he couldn’t quit. There was, however, a major stumbling block: the club were virtually bankrupt and £185m in debt.

“Real Madrid,” said Perez, three months after being elected, “is seriously ill.”

The cure was ingenious and intrinsically Perez. He sold La Ciudad Deportiva – the club’s training ground on the northern tip of the city centre, an area of prime real estate – to the Madrid local authority for £298m, who raised the cash mainly through taxes paid by every madrileno, Atletico and Rayo Vallecano fans included. Perez’s enchufes swept everything through with speed. For most, it would take two or three years of Spanish red tape. Perez did the deal in 24 hours.

To rebuild the training ground, Perez bought land by Barajas airport for a fraction of what he’d received. He had wiped out Real Madrid’s debts at a stroke. Crucially, he had money left over. So, in the summer of 2001 he broke the world transfer record again to sign Zinedine Zidane for £46m. The following year he bought the Brazilian Ronaldo. Real Madrid already had Figo, Raul and Roberto Carlos. “Of the 10 best players in the world,” said club captain Fernando Hierro, “we’ve got five.” He wasn’t exaggerating. David Beckham arrived in 2003.

“Nothing is more profitable than recruiting a superstar,” said Perez, citing Ronaldo as the only player who could score 25 goals a season and “pay for himself”.

In 1999/00, not one Bernabeu fixture had sold out. In 2000/01, 18 of 19 did. The season after that, they all did. It’s hard to overstate the effect Los Galacticos had on Spanish football.

Perez encouraged his superstars to sign over their image rights to the club. “If one of our players does an advert for custard, he might earn €120,000,” the club president reasoned. “If he filmed the same advert in a Real Madrid shirt, he would make 10 times that.”

It was this canny business which kept the club in the black. In announcing the team’s own website as its title sponsor for 2001/02, Perez declared that he wouldn’t “stain” Real Madrid’s famous white strip unless it was for “a scandalous amount of money”. Alerted to the possibility of sponsoring the biggest club in the world, mobile phone company Siemens duly offered €12m per season.

In those early years, Vicente del Bosque’s Galacticos delivered on the pitch as much

as they did off it. “They might score two goals – we’ll score three,” Zidane told FFT in 2013. “It was fun.”

Each Galactico came to be defined by their first campaign at the club. In 2000/01, Figo inspired Madrid to a dominant league title, and 2002/03 saw Ronaldo finish as La Liga’s top scorer and win – somehow – the only top-flight title in his career, not to mention being applauded off at Old Trafford following one of history’s most memorable hat-tricks.

The season that all madridistas remember most fondly, though, is Zidane’s 2001/02. Initially, the Frenchman struggled, but soon he was soaring. His sublime left-footed volley in the Champions League final against Bayer Leverkusen remains the best goal ever scored in European football’s showpiece event (sorry, Gareth), and it cemented the dynasty.

This goal happened 18 years ago today - which, coincidentally, is the same length of time that Roberto Carlos cross hung in the air before Zidane leathered itpic.twitter.com/g71Og1WSUdMay 15, 2020

“That was the thing I needed at this club – the trophy I didn’t have,” Zidane later told FFT. “That goal was perfect. People say, ‘Well, he cost a lot but he won the Champions League’.”

Beckham and the beginning of the end

Paying for those goals was half the problem. In 2003, some 80 per cent of the club’s budget was spent on wages. Perez wanted that figure down to 50 per cent, but the only way to do it was to scrimp on players who didn’t fall into the Galactico bracket.

During the summer of 2003, McManaman, Fernando Morientes, Claude Makelele and captain Fernando Hierro were all allowed to leave, the latter with no proper farewell after 14 years’ service, due to his open intransigence towards Perez’s Galacticos policy. None were adequately replaced. Neither was Del Bosque, unceremoniously dumped after winning the La Liga title in 2002/03. Five coaches in two and a half years followed.

The Zidanes y Pavones strategy of mixing the stars with youth-teamers – named after their French talisman and Francisco Pavon, a young, club-trained central defender – was as much financial necessity as philosophy to maintain a Spanish core. The quality simply wasn’t there, and standards slipped.

Beckham came to symbolise the last days of Rome. England’s captain was one of Europe’s best players, but it was Goldenballs’ popularity in emerging markets that most enticed Perez. That the king of crossing was coming to play centrally, replacing Makelele – the one Madrid midfielder who actually defended – was proof. “Why buy another layer of gold paint for your Bentley,” Zidane asked at the time, “when you are selling the whole engine?”

It was nothing personal, though. Beckham’s team-mates were and are always quick to highlight his professionalism at the Bernabeu.

“It’s not his fault at all that they signed him with this aim or that one,” Figo told FFT years later. “The fourth year was when we started to divert a bit. We went around the world, from Los Angeles to China... we started to break the rules a bit of what a football team is.” Such as actor Kuno Becker sitting on the Madrid bench for scenes that would appear in the film Goal II, for example.

The 2003/04 season would prove to be the beginning of the end. Real Madrid began well under their new coach, Carlos Queiroz, but by March a thin squad was stretched to breaking point. When on-loan Morientes scored in both legs for Monaco to knock his parent club out of the Champions League, the irony was palpable. Scarred, Madrid slipped from first to fourth in La Liga during the campaign’s final weeks, and it would be seven years before they next won a Champions League knockout tie.

“‘Galactico’ is just a name,” Figo told FFT in 2013. “It was a nickname constructed to sell, and that’s it.”

Knives out in Barcelona

Barcelona had been a shambles ever since Figo’s shock exit, finishing 4th, 4th and 6th. “There was a really bad dynamic,” Carles Puyol later explained to FFT. “We didn’t even compete. At the very least, that’s what your fans demand of you.”

Joan Laporta succeeded Gaspart as Barça’s new president in June 2003. A good-looking, compulsive, fortysomething lawyer, he could hardly have resembled Florentino Perez less.

Image was everything to Laporta, who was determined to re-establish Barcelona as the team of Catalonia. He had strategists, a press agent and even a documentary team following him, in the first professionally-run presidential campaign in Spanish club football history. And most importantly, he had a plan.

While vice-presidents Ferran Soriano and Marc Ingla worked the numbers, Sandro Rosell – a former high-ranking Nike executive in South America – provided a dressing-room link to director of football Txiki Begiristain and up-and-coming head coach Frank Rijkaard. No matter that they’d promised to sign Beckham if elected. Second prize, using Rosell’s Nike contacts: Ronaldinho.

In polar opposition to Beckham at the Bernabeu, the 23-year-old, buck-toothed Brazilian – “too ugly” for Real Madrid, one of their directors had said a year earlier – fitted perfectly with the new Barcelona regime.

His home debut against Sevilla kicked off at five past midnight on September 3, as La Liga refused to allow Barça to move the fixture date despite an upcoming international break. At 1.24am, Ronaldinho crashed an unstoppable 30-yard shot in off the bar.

🇧🇷 Ronaldinho: “The most memorable match was the first one, It started at 0.01am... It was the first and only time that I played at that time. But it was no problem – that’s my favourite time of day...” pic.twitter.com/8yqV3XniGEJuly 19, 2019

There was only one problem. Barcelona kept losing. As 2003 turned to 2004, Barça, fresh from a 5-1 humping at Malaga and first Clasico defeat at home in 20 years, fell 18 points behind their eternal rivals. The knives for Laporta sharpened– literally. Els Boixos Nois, an ultras group furious at being phased out of a family-friendly Camp Nou, plastered the walls of Laporta’s home with graffifiti death threats.“Found you,” read one.

Edgar Davids’ €2m loan move from Juventus wasn’t too popular, although it helped to free a scheming Xavi from his defensive shackles. From January 11 to May 1, 2004, Barça won 14 and drew three of their 17 league games, including a Xavi-inspired 2-1 triumph at the Bernabeu, and recovered to finish 2nd.

Next, the contacts of vice-president Rosell delivered style and Champions League-winning experience in two of the 2004 finalists, Ludovic Giuly and Deco. Most important was Samuel Eto’o, who’d been at Mallorca since 1999/00 but was still technically co-owned by Real Madrid. He was exactly what Barça needed: a proven goalscorer motivated to rub Madrid’s noses in it. He hit 25 goals in his first season as Barcelona romped to the 2004/05 title.

Everything had clicked. In particular, the core of La Masia-schooled Xavi, Puyol, Victor Valdes and Andres Iniesta chimed with the fanbase in a way that Real Madrid’s Galacticos hadn’t.

“It was like we had returned to Johan Cruyff and the Dream Team,” Xavi later told FFT. “In a 4-3-3 with the focus on possession, we got back our dream – our ilusion.” Their hope.

Better was yet to come. At the Bernabeu in November 2005, Rijkaard surprisingly selected an Argentine teenager for only his second start of the season, and his first-ever appearance against Real Madrid. Within 14 minutes, Lionel Messi had his first Clasico assist – Eto’o, the goalscorer. Not to be outdone, Messi’s mentor, Ronaldinho, scored a brace. So mesmeric was his first goal, the Brazilian sitting Sergio Ramos on his backside before caressing the ball past Iker Casillas, that the cathedral of madridismostood to applaud. “A stratospheric Ronaldinho retires the Galacticos,” bemoaned Marca, the Madrid-based sports daily.

In May, Barça won the Champions League, beating Arsenal in the final. Laporta, front and centre, revelled in the glory. Perez had fallen on his sword four months earlier, conceding “we need a change of direction”.

The king was dead. Long live the king.

#OnThisDay 2006Barcelona beat Arsenal 2-1 in the Champions League Finalpic.twitter.com/M9oHwYz9nkMay 17, 2020

"Football has a god. Messi is Maradona, Cruyff and Best rolled into one"

Barça, however, are predisposed to shooting themselves in the foot. Seldom is trouble far from the surface.

In the summer of 2005, vice-president Rosell had resigned and taken eight others with him – including today’s head honcho, Josep Maria Bartomeu – after accusing Laporta of changing as a person. Four weeks before the Champions League final against Arsenal, Rosell released the book Benvingut al mon real, ‘Welcome to the real world’, a tell-all exposé on the Laporta administration. In 2008, vice-president Soriano also resigned.

On the pitch, things were little better, in spite of Messi’s inevitable rise to superstardom. Out of shape and out of motivation, Ronaldinho was increasingly resembling his Spitting Imagepuppet which just smiled and shouted “fiesta”.

Under their new president, Ramon Calderon, Real Madrid took advantage.

Fabio Capello arrived to stamp some more authority on a squad lacking a backbone – or Galacticos. Figo had joined Inter; Zidane had retired; Ronaldo would join Milan in January. Beckham remained but Capello made it clear he wasn’t wanted, only to change his mind once impressed by the midfielder’s application.

In their place came players Madrid needed: Fabio Cannavaro and Ruud van Nistelrooy in 2006, then Arjen Robben and Wesley Sneijder a year later. Van Nistelrooy scored 64 goals in 96 appearances.

With Barcelona struggling, Los Blancos won successive league crowns. In possibly the most Real Madrid move of all time, Capello got the sack after the first title for not winning stylishly enough. He was replaced by the prickly former Barça and Madrid playmaker Bernd Schuster, who presided over a goal-hungry title-winning campaign. The Galacticos were gone but the trophies had returned, and that was enough.

Come May’s Clasico, the league long since wrapped up, Madrid twisted the knife. Barça, 18 points behind their rivals, had to perform the pasillo: the dreaded guard of honour.

“Barça, it’s just here,” guffawed Marca’s front page, complete with helpful dots outside the Bernabeu tunnel where all the players should stand. Eto’o had made sure he was suspended and didn’t travel. Madrid won. 4-1.

The next day, Laporta announced Rijkaard’s successor: a former ball boy and club legend from the Catalan interior, whose hero was local protest poet and songwriter Lluis Llach.

B team boss Josep Guardiola i Sala was now Barcelona’s head coach.

Like his footballing mentor, Johan Cruyff, two decades earlier, Guardiola trusted both himself and the Barcelona way.

Almost immediately, he told Ronaldinho to find himself a new club. There was a new zip, especially when Spain’s victorious Euro 2008 squad members started arriving at the team’s pre-season training camp in Scotland. Sergio Busquets, a central cog in Guardiola’s midfield for Barça B, was immediately promoted.

“I remember thinking after the first training session at St Andrews – always with the ball, great pressure, intensity from Pep – ‘things are going to go well for us’,” Xavi later told FFT.

Most important was getting Messi on board. The relationship between player and manager was initially frosty, as the sulky 21-year-old was still fiercely loyal to Rijkaard, who’d given him his big break. However, relations improved after Guardiola, against club orders, allowed Messi to join up with Argentina at the Beijing Olympics. The manager himself valued his own gold medal with Spain in 1992.

Barcelona picked up one point from their first two matches, against Numancia and Racing Santander, but a 6-1 rout of Sporting Gijon was a sign of things to come. “Trust in him,” Puyol told FFT last year, “and results usually follow.”

The machine Pep built established a 12-point lead, but a relentless Real Madrid – now with Juande Ramos in charge – had cut it to four before May’s Clasico. Guardiola didn’t panic. He played Messi as a false nine for the first time, with Eto’o and Thierry Henry either side. Messi created one goal and then scored two more in a staggering, era-changing 6-2 win for Barça. Xavi helped himself to four assists.

“Football has a god,” wrote Sport. “Messi is Maradona, Cruyff and Best rolled into one.”

The Copa del Rey arrived a month later, then the Champions League trophy, to complete an historic treble in Guardiola’s first season.

“That season was my highlight at Barcelona,” Xavi later told FFT. “Nothing compares to that season, and I don’t think anything ever will. It is the best season in Barça’s history; the best football I’ve ever seen from a team.”

Guess who's back

That summer, Florentino Perez returned to the Bernabeu. A week after his second coming, the Real Madrid president broke the world transfer record to buy Kaka for €67m, and then broke it again to recruit Cristiano Ronaldo for €94m. Karim Benzema, Raul Albiol, Alvaro Arbeloa and Xabi Alonso also arrived, the latter three in an attempt to provide a Spanish core to the team. Perez had been learning.

“We have to do in one year what we would usually do in three,” said Perez. It wasn’t hard to notice the subtext: he wanted the €250m bomba of CR7 & Co. to overshadow Barça’s season of seasons. Not to be outdone, Laporta engineered a deal for Zlatan Ibrahimovic.

If there was any doubt that El Clasico was now Spain’s biggest culebron, or soap opera, it disappeared in 2010. Perez the pantomime villain was already back; now Jose Mourinho crossed the divide to manage Real Madrid. In the same summer, Rosell returned to become Barcelona president. Four years later he was jailed for money laundering, and replaced by Bartomeu, before being acquitted in 2019.

Figo moving to Real Madrid in 2000 was the turning point. El Clasico, though, is an evolving story. Barcelona are now more likely to splash the cash on playthings they don’t necessarily need – Philippe Coutinho, Ousmane Dembele, Antoine Griezmann – as the ‘mes que un club’ mantra has increasingly worn away.

In Madrid, the opposite has happened.

“If you look at Barça’s culture,” said a Real employee in 2009, his eighth year at the club, “it’s the same at under-12 and under-14 levels. The under-16s play the same way as the first team. You don’t find that at Madrid, and you wonder what their style is.”

That employee overhauled the Real Madrid academy, with a Barcelona vision, beginning with the B team. Dani Carvajal, Nacho and Marcos Llorente all came through Los Blancos’ resurgent Fabrica to lift the Champions League.

Today, he is the only manager in history to win three European Cups in a row. His name is Zinedine Zidane.

Andrew Murray is a freelance journalist, who regularly contributes to both the FourFourTwo magazine and website. Formerly a senior staff writer at FFT and a fluent Spanish speaker, he has interviewed major names such as Virgil van Dijk, Mohamed Salah, Sergio Aguero and Xavi. He was also named PPA New Consumer Journalist of the Year 2015.